I grew up under the watchful gaze of my dead grandmother lying in her coffin. Her funeral had been meticulously documented and a series of 4" × 6" black-and-white photographs had been printed, then framed, to hang in the living rooms of my uncle’s spacious house in Haiti and my parents’ crowded two-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn. My grandmother’s “shadow” followed me from even before I was born, right into my transition into a new life in New York City at age twelve. It followed me, that is, until the photographs were lost: one during a move in New York, the other during the Haiti earthquake of 2010.

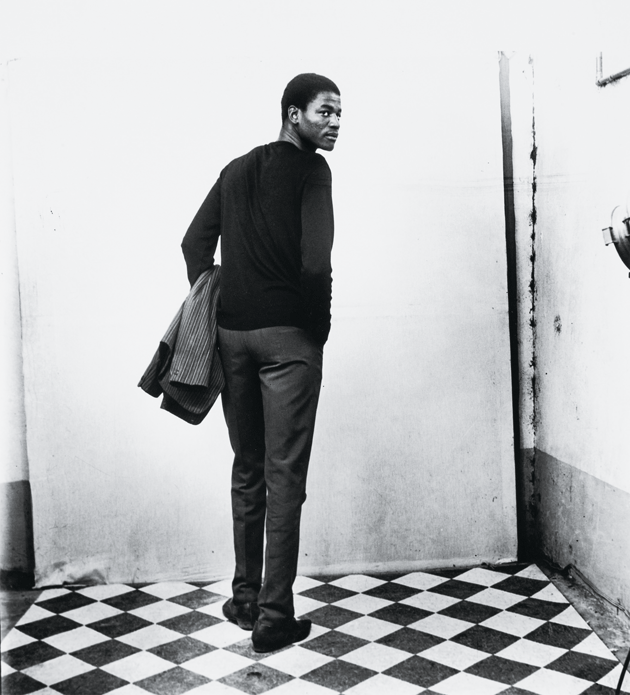

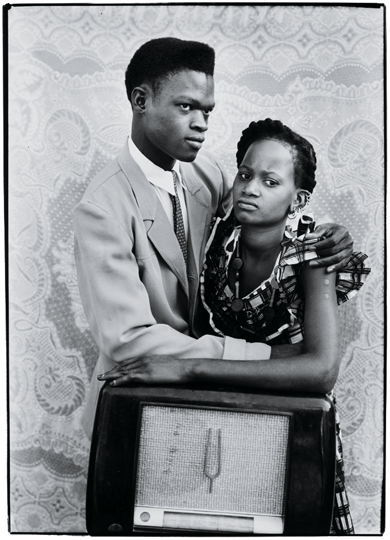

Untitled photograph, 1952–55, by Seydou Keïta. Courtesy The Walther Collection and CAAC–The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva

There was no taboo associated with funerary photography in my family. In many cases, there were only two sets of pictures of my eldest relatives: one of them posing in a photo studio on their wedding day, the other taken on their way to be buried. Before the widespread accessibility of cameras, photographs like my grandmother’s, and even some of mine, were long deliberated over and saved for. They were never meant to be candid or casual. And they were costly, sometimes requiring the equivalent of a day’s salary per sitting. The photographer and the photographed knew that they were creating heirlooms, calling cards to generations yet unborn.

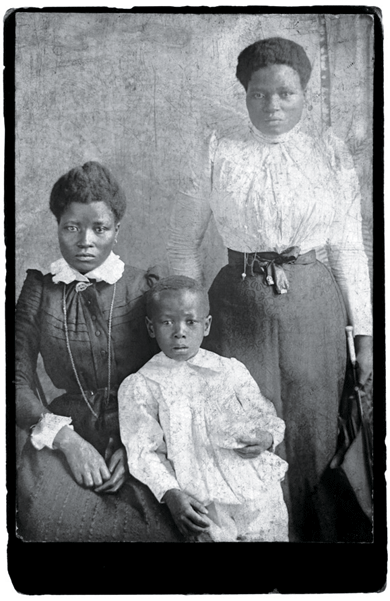

“Ouma Maria Letsipa, née van der Merwe, with her daughter, Minkie,” c. 1900, Scholtz Studio, Lindley, South Africa. From Santu Mofokeng’s series The Black Photo Album/Look at Me: 1890–1950, 1997. Courtesy The Walther Collection and Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

Nearly twenty years ago, after I published my first novel, a newspaper reporter asked me to send him some family photographs via messenger. I stupidly sent him an entire album filled with irreplaceable pictures, which, after pulling a few for his article, he promptly discarded. Many I never saw again, including several taken in Port-au-Prince photo studios between my fourth and twelfth birthdays, to send to my mother and father, who had moved to New York and left my brother and me in the care of my uncle and his wife. These photo sessions were the equivalent of birthday parties, which I never had, and the resulting pictures were my only keepsakes. When the reporter called, I was eager for the world to see these images that meant so much to me. They were created for private use, but they also seemed, in a way, public: after all, they were taken with distant people in mind, even if those people happened to be my parents. To me, those photographs had an unshakable permanence — they seemed too monumental to simply vanish. When I found out they were gone, I felt as if part of my life had been erased. Had my family’s photographs been lost in a fire or a flood, they might have been easier to mourn. That I had contributed to their disappearance was almost impossible to accept.

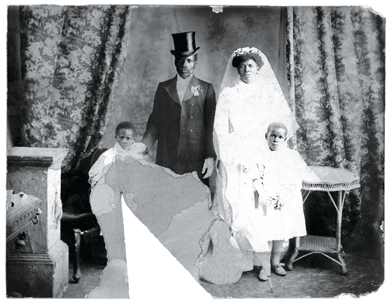

“Ephraim Maloyi’s wedding portrait,” c. 1890 (photographer unknown). From Santu Mofokeng’s series The Black Photo Album/Look at Me: 1890–1950, 1997. Courtesy The Walther Collection and Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

The same feeling of both fragility and indestructibility is evident throughout the three volumes in the African photography series published by the Walther Collection, which is based in Neu-Ulm, Germany, and New York City. “These are images that urban black working- and middle-class families had commissioned, requested, or tacitly sanctioned,” the South African photographer Santu Mofokeng writes in his essay “The Black Photo Album/Look at Me” in the series’ first volume, Events of the Self: Portraiture and Social Identity. “Dead relatives have left them behind, where they sometimes hang on obscure parlor walls in the townships.”

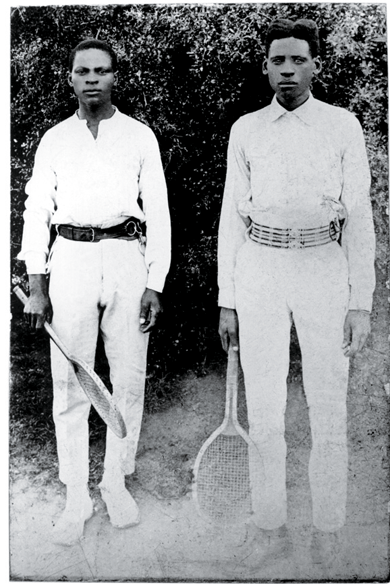

“Moeti and Lazarus Fume,” 1920 (photographer unknown). From Santu Mofokeng’s series The Black Photo Album/Look at Me: 1890–1950, 1997. Courtesy The Walther Collection and Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

The photographs Mofokeng is writing about date from between 1890 and 1950. Some were taken in homes, others in studios. Black South Africans stand or sit, alone or as couples, many in large family groups, celebrating weddings or a baptism. A few of the men are wearing those days’ version of tennis whites — long trousers and long sleeves — while casually holding their rackets. Some of the women are wearing lace blouses and wide-brimmed church hats; others lean on their embroidered umbrellas or on one another.

When people walk into a photo studio wearing their best finery, they demand control over how they are perceived, and they are aided by various combinations of props (wall prints, radios, bicycles, or even a single flower) and camera tricks (which might make a subject appear as his own twin, or seemingly put him in the presence of angels and ghosts). I was particularly intrigued by the studio portraits of the Malian photographer Malick Sidibé, in which we see most of his subjects from the back. Many of the photographs show no face at all, just a man’s hat or a woman’s elaborate hairstyle. In others we get a fleeting glance of a face, tilted slightly over the shoulder, as in the image of a young man with his jacket tucked under his elbow as he approaches the white backdrop.

Untitled photograph, 1949–51, by Seydou Keïta. Courtesy The Walther Collection and CAAC–The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva

Portraiture, argues the Nigerian-American curator Okwui Enwezor, is

a game of theater and masquerade, premised on the artifice of self-construction. The figure in the image, more than being depicted and displayed, insists on being seen, to be looked at, and desired.

This yearning to be desired is most identifiable in the portraits that appear to have been meant for private use, such as many by the celebrated Malian portraitist Seydou Keïta. The desire not to be desired is here, too. In what looks like an engagement portrait gone wrong, a young woman seems more willing to hug Keïta’s radio than the young man who is trying to grasp her in his arms. Her defiant glare makes us feel like voyeurs.

“Structures: Luke Kgatitsoe in his house, Magopa, Ventersdorp district. 21 October 1986,” by David Goldblatt. Courtesy The Walther Collection and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

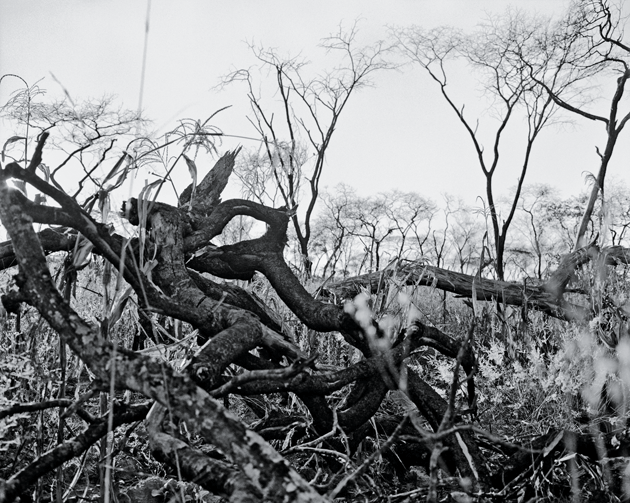

“Abandoned cornfield near Indungo I,” 2009, by Jo Ractliffe, from her series As Terras do Fim do Mundo. Courtesy The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

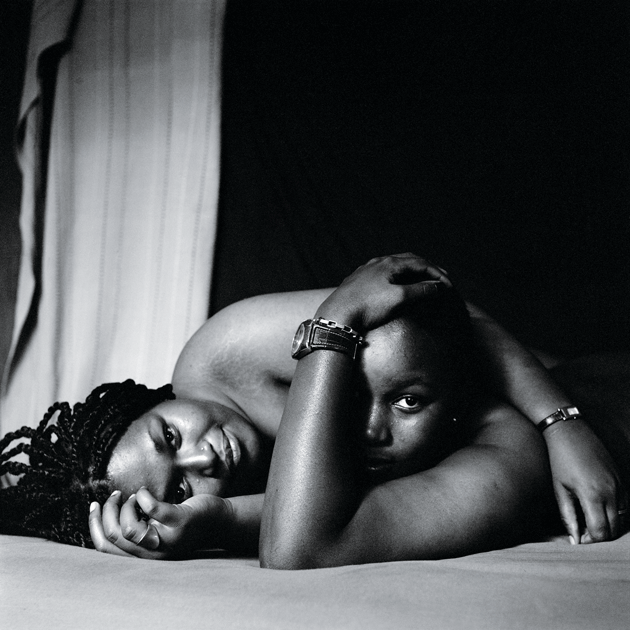

“Apinda Mpako and Ayanda Magudulela, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2007,” by Zanele Muholi. Courtesy the artist; Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg; and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York City

Most prominently featured in this series is the work of South African photographers, artists, and documentarians. David Goldblatt’s apartheid-era photographs take center stage, but the volume Appropriated Landscapes also features work from Angola, Namibia, Mozambique, and even the United States. And as the photographer Zanele Muholi’s intimate portraits of lesbian bodies, alone or intertwined, show, the landscape in question can be the human form.

Muholi considers herself a visual activist; her work depicting lesbians not as victims of hate crimes or so-called curative rapes, but as loving and loved, is part of a larger political project. In 2009, Lulu Xingwana, South Africa’s minister of arts and culture, walked out of a Johannesburg exhibition featuring Muholi’s photographs, calling them immoral and “against nation building.” Muholi’s house has been burglarized and hard drives full of her photographs stolen. In April 2013, after she won a Freedom of Expression Award from the Index on Censorship, her work was chosen for the Venice Biennale. In an interview at the time, speaking of what was lost in the theft, she told a South African journalist: “It’s not about the photos, it’s about the stories behind them.”

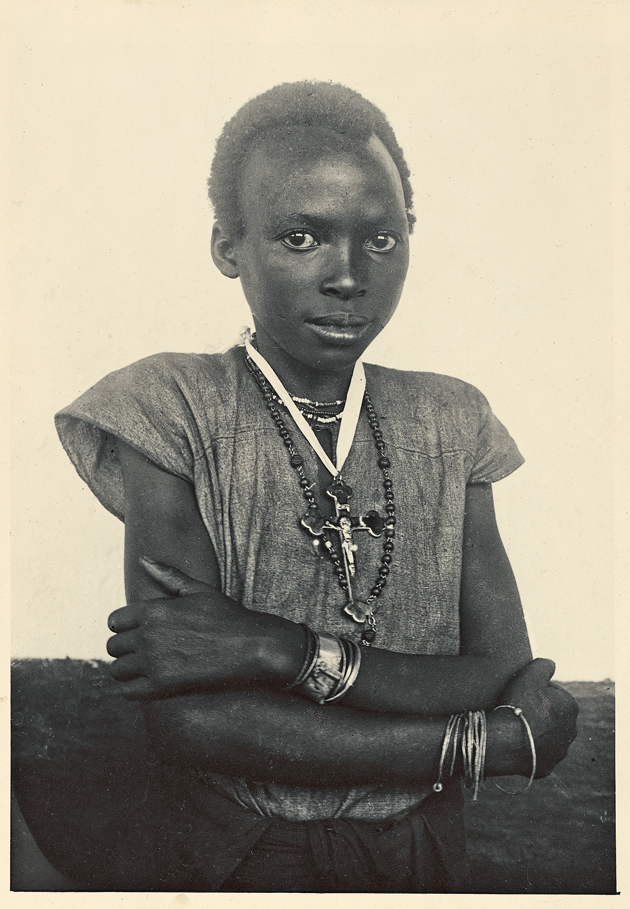

Outdoor portrait of an unidentified person, East Africa, first half of the twentieth century, by an unidentified photographer. Courtesy The Walther Collection

Appropriated Landscapes is likewise about more than the photographs. It’s about prisonlike workers’ dormitories or hostels, electric poles that look like crosses, skyscrapers framed like ribs, fog-draped mountains and beaches at high tide, cornfields and minefields, the evening exodus to the townships, or the Saturday-morning shopping trips, homesteads and homelessness, and burials in private cemeteries or mass graves.

Emblematic is the story of Luke Kgatitsoe, who was photographed in the South African village of Magopa by Goldblatt in 1986. Two years earlier, he and his several hundred neighbors had been forced onto trucks by police and transported 150 miles from their village to a new settlement. Their homes were bulldozed and their land reallocated to white farmers. Kgatitsoe and the others were allowed to return to clean the graves of their ancestors. Once there, they refused to move. They eventually won resettlement rights in the courts, but only part of the land was returned to them. Kgatitsoe was photographed, in Magopa, wearing an impeccable three-piece suit while sitting on a pile of broken stones, as the white farmers’ cattle roam in the distance. He has the look of a man dressed for his own funeral. His exasperated face is a geography unto itself, his body a human silhouette trying to reclaim part of the lost veld behind him. His portrait is another reminder of the constant battle to appropriate and reappropriate African landscapes, be they bodies or ground.

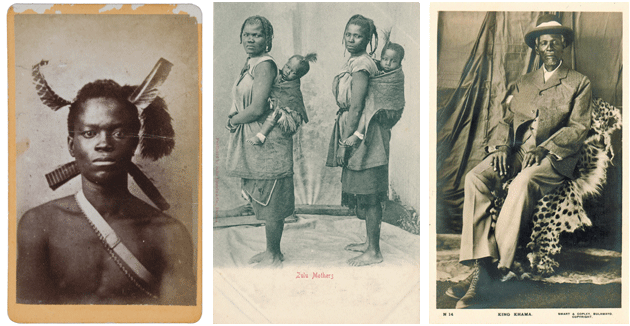

Left to right: Studio photograph of an unidentified man, South Africa, carte de visite, last third of the nineteenth century, by G. F. Williams; “Zulu Mothers,” postcard c. 1903 (photographer unknown), published by Sallo Epstein & Co., Durban, South Africa; “King Khama,” postcard c. 1920s (photographer unknown), published by Smart & Copley, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. All courtesy The Walther Collection

The third and most recent addition to the series, Distance and Desire, focuses on historical photography. This volume attempts to reframe ethnographic and anthropological images — postcards, cartes de visite, books, and photographic albums — by placing them alongside contemporary reconfigurations.

One of the most recognizable (and sexualized) images from late-nineteenth-century Southern Africa is that of the Hottentot woman. Though Sarah “Saartjie” Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman who was used as a freak-show attraction in Europe, is probably the most famous of the so-called Hottentot Venuses, there were many others whose likenesses were distributed throughout the world on postcards. Most of the photographs in this volume were in their time meant to be salacious, a type of colonial porn, with submissive-looking black bodies presented partly or fully naked. The focus is on archetypes (Native Policemen, Zulu Mothers) or actions (dressing hair, carrying children). Even the tribal dress is meant to be titillating, especially the courting and fighting garb; the Zulu warriors, for example, are choreographed to look more decorative than menacing. Some of the subjects resist through their postures or dour expressions. In these pictures, no one has a name — and even if they did, it would not be the one bestowed by their mothers or fathers. It might be something like Venus.

In her essay on these postcards, Christraud Geary, senior curator of African and Oceanic art at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, notes that between 1898, when the first postcards emerged, and 1918, an estimated 200 to 300 billion postcards were printed worldwide, coinciding with the golden age of imperialism.

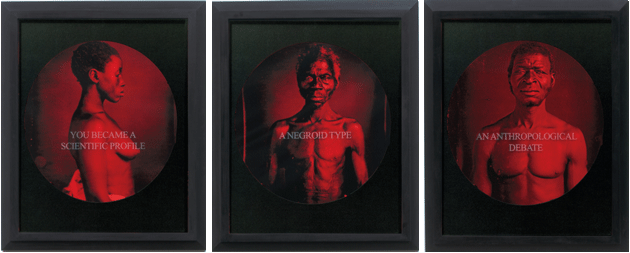

Left to right: “You Became a Scientific Profile,” “A Negroid Type,” and “An Anthropological Debate,” from Carrie Mae Weems’s series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, 1995–1996. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York City

Which brings us to contemporary reconfiguration, which is one way to give voice to silenced and misrepresented subjects. In From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, a series of prints with text sandblasted on a covering layer of glass, the African-American photographer, video artist, and recent MacArthur fellow Carrie Mae Weems uses color, often a bright red hue, to underscore monochrome ethnographic images whose overlaid text at times directly addresses the subjects:

you became a scientific profile

a negroid type

an anthropological debate

& a photographic subject

Weems is boldly calling out to the past almost as loudly as those men and women might have wanted to call out to the future.

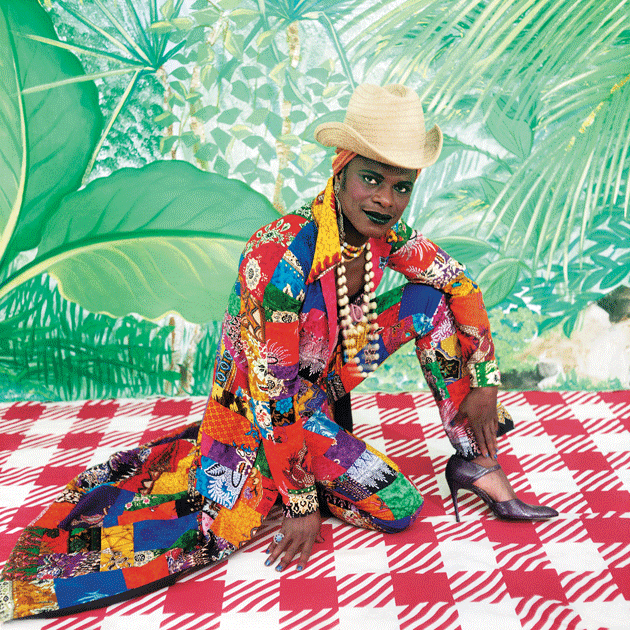

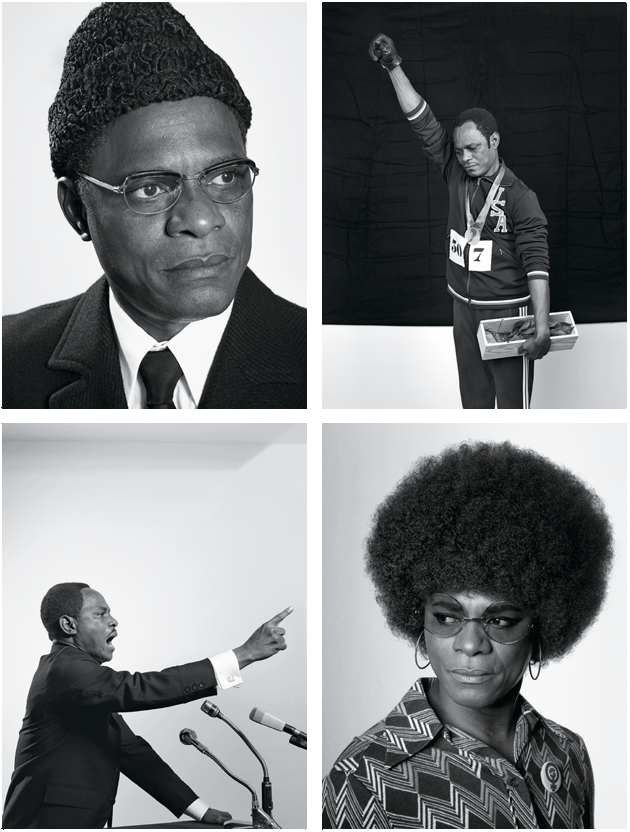

Four photographs, each titled “Self-Portrait,” 2008, from Samuel Fosso’s series African Spirits. All courtesy The Walther Collection and Jean-Marc Patras, Paris

But just as striking is the work of Samuel Fosso, a Cameroonian-born photographer who grew up in Biafra during the Nigerian civil war and now lives in the Central African Republic. He has made a series of self-portraits in which he poses as prototypical or iconic Africans and African Americans. Dressed as “the Liberated American Woman of the 1970s,” or as Haile Selassie or Nelson Mandela, he reconfigures what one curator in the volumes calls the “triangulation of the photographer, the sitter, and the viewer”: he makes himself all of them. Who, this series asks, is gazing in the end, and who is saying Look at me? No one, and all of us.