Discussed in this essay:

Self-Help Messiah: Dale Carnegie and Success in Modern America, by Steven Watts. 592 pages. $29.95. Other Press.

Blessed: A History of the American Prosperity Gospel, by Kate Bowler. 352 pages. $34.95. Oxford University Press.

The Holy Spirit, Your Financial Adviser: God’s Plan for Debt-Free Money Management, by Creflo Dollar. 342 pages. $22. FaithWords.

Dale Carnegie called his self-help book, written at the nadir of the Great Depression, How to Win Friends and Influence People, as if it were a relationship manual. But it’s no accident that at the outset he introduces Charles M. Schwab, head of U.S. Steel,

one of the first people in American business to be paid a salary of over a million dollars a year (when there was no income tax and a person earning fifty dollars a week was considered well off) . . .

Nor is it an accident that when he was etching his public profile, Carnegie decided to take advantage of a lucky homophony, casting off his father’s “Carnagey” for the spelling used by Schwab’s famous boss Andrew. Even if he didn’t dare utter its name, Carnegie knew the pathology he was treating: money-deficit disorder.

By invoking these winners, Carnegie no doubt meant to persuade his readers that the words he was about to reveal — the key to Schwab’s success, according to the million-dollar man himself — would “all but transform your life and mine if we will only live them.” The secret? “ ‘I consider my ability to arouse enthusiasm among my people,’ said Schwab, ‘the greatest asset I possess.’ ” And how did Schwab do it? According to Carnegie, anyway, by never criticizing others, by giving “honest and sincere appreciation,” thus “arous[ing] in the other person an eager want.” Updating, if unconsciously, Jesus’ injunction about neighborly love, the book promises that if you harness these erotics, you can’t help but succeed.

The Dale Carnegie who emerges from Self-Help Messiah, Steven Watts’s fine new biography, is more than an übersalesman dispensing tricks of the trade to the Willy Lomans of midcentury America. He is an apostle of a new gospel preached to the new man who emerged toward the end of the nineteenth century. His fate was no longer in the hands of an angry God, or even a benevolent God who would bestow happiness in the hereafter; nor did he have to settle for whatever station he had been born into. Self-invention was the new route to salvation, and if he failed to take it, he would be condemned to the earthly equivalent of what awaited Calvin’s sinners — the hell of economic and social failure.

The self unbound from divine destiny was bound to be anxious about exactly what it was supposed to be doing with itself, and long before Carnegie wrote his book, phrenologists, Christian Scientists, theosophists, Emersonians, Swedenborgians, and mesmerists had fanned out across the country to hawk cures for this modern worry, promising surefire ways to achieve health and wealth amid the hurly-burly of a free country. For all their differences, these philosophies have gone down in history as the various tributaries of the New Thought movement, united by their faith in “mind power.” As Watts describes them, New Thinkers as disparate as Christian Science’s Mary Baker Eddy and the animal magnetist Phineas Quimby “believed that hidden mental resources could be retrieved and mobilized to increase emotional vigor, social success, and material accumulation” and offered their own methods for tapping these resources.

Carnegie was born in 1888 in Missouri to a “hardscrabble farmer” father and a “devout and dynamic lay preacher” mother. The family, as he recounted years later, lived through floods that wiped out their crops and diseases that ravaged their hogs until, after “ten years of hard, grueling work,” his parents were “not only penniless, [but also] heavily in debt.” Those hard times had left their mark. “I was full of worry in those days,” Carnegie once wrote — a chronic state that he later called an “inferiority complex” and that Watts explains as the unsurprising outcome of “the ongoing tension between poverty and piety” inflicted on a “sensitive child [who] could not understand why their efforts, and their upstanding values, seemed to produce only failure.” To the young man emerging from this childhood misery, the New Thought promise that all adversity could be overcome through strength of mind was irresistible.

Carnegie first encountered these ideas in 1904, when he enrolled at the State Normal School in Warrensburg, Missouri. As he later recounted,

I studied biology, science, philosophy, and comparative religion. I read books on how the Bible was written. I began to question many of its assertions. I began to doubt many of the narrow doctrines taught by the country preachers . . . I stopped praying. I became an agnostic. I believed that all life was planless and aimless. I believed that human beings had no more divine purpose than had the dinosaurs . . . I sneered at the idea of a beneficent God who had created man in his own likeness.

Carnegie was surrounded by exemplars of this agnosticism, young men unyoked from piety like his mother’s, free to invent themselves as they pleased.

I looked around and saw that the men who had won the debating and public speaking contests were regarded as the intellectual leaders in college. They were in the limelight . . . Everybody knew them! Everybody knew their names! . . . I said, “maybe I can do that.”

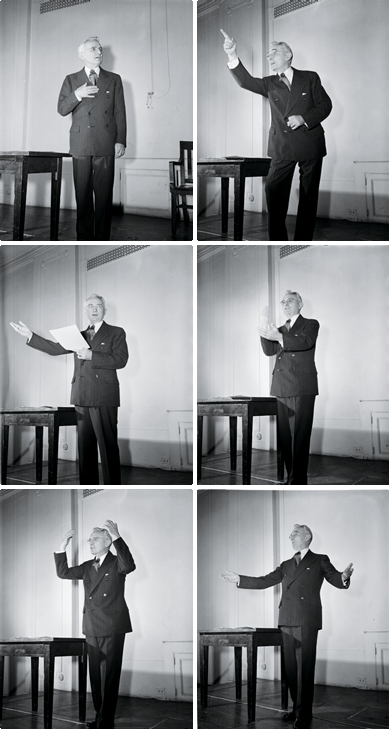

He became a champion college orator, a résumé entry that helped him with his inferiority complex and eventually persuaded his first employer to hire him. Watts tells us that Carnegie was the beneficiary of a change in the nature of competitive rhetoric. Speech-making, once guided by “rules of formal declamation,” had become less constrained and now encouraged “the free play of individualism” and “utiliz[ed] the voice and body for a delivery that was ‘natural.’ ” This shift reflected the larger cultural turn toward the notion of the world as a venue for the efflorescence of the limitless mind. With his preacher’s charisma and conviction, Carnegie was perfectly suited to this new world.

Carnegie’s first stint as a salesman — traveling the Midwest selling correspondence courses to farmers — was a bust that left him penniless and sobbing in his rented room, but even when he found success selling bacon and soap for Armour and Company in the northern prairie, he longed for the self-expression he had enjoyed in college and the modest celebrity it had bestowed on him. He aspired to the traveling-lecturer circuit and set his eyes on Chautauqua. When he described this ambition to an Episcopal priest he met in the caboose of a freight train (and Watts’s story is full of just this kind of delicious detail), the priest suggested he go to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City, a school whose alumni would eventually include actors ranging from William Powell to Robert Redford.

At the academy, Watts tells us, Carnegie learned that acting was “an expression of the ‘total man’ — the union of imagination, mind, feeling, and technique.” Soon he was playing multiple roles in the romantic melodrama Polly of the Circus for crowds around the country, but within the year he had decided that theater life was too uncertain for him. After a series of unsuccessful car-sales jobs left him broke once again, Carnegie decided to put his expressive skills to work teaching public speaking at YMCAs in New York and other cities, an endeavor that by 1915 had proved popular enough to spur the publication of his first self-help book, The Art of Public Speaking.

That book signaled the themes that would eventually make Carnegie’s fortune. “We choose our characters by choosing our thoughts,” he told his readers. By “character” Carnegie meant something other than the “old-fashioned, Victorian standard with stern moral values and genteel decorum,” Watts explains. After the dislocations of the fin de siècle, the struggle to refine character out of the raw ore of humanity was giving way to the struggle to develop what psychologists were just beginning to call “personality” — that malleable set of traits whose “social masks,” as Carnegie wrote, “could be taken off and on at will.” Putting on a mask had its own rigors: “You must actually ENTER INTO the character you impersonate, the cause you advocate, the case you argue — enter into it so deeply that it clothes you, enthralls you, possesses you wholly.” This protean confidence, Carnegie said, must be balanced by an appearance of humility, so as to flatter the listener — “self-preservation is the first law of life, but self-abnegation is the first law of greatness . . . Dynamite the ‘I’ out of your conversation” — and yield the “emotional force” that allows one man to arouse want in another.

The ideal self may have been a cipher, but there was one quality that we all shared and that made self-abnegation a winning strategy. The downcast, the depressed, the discouraged — people only wanted to be well-liked. Earlier in the twentieth century, the worried masses had been driven to doctors for their hysteria and neurasthenia, but by 1936, when How to Win Friends was published, patent medicines and rest cures had fallen out of favor as treatments for middle-class malaise. Carnegie thought he knew why. “Many persons call a doctor when all they want is an audience,” he wrote. If those earlier cures had worked, it was only because they had inadvertently satisfied this need for recognition.

How to Win Friends was an almost immediate success, amassing sales of 250,000 copies in its first three months and more than 30 million in the next few decades. Shedding the arcane metaphysics of New Thought in favor of the hardheaded pragmatics of American business, Carnegie provided precisely the therapy a nervous populace needed — and, to judge from the book’s continued annual six-figure sales, the therapy it continues to need. He also opened the way for all the self-help gurus to come, from Napoleon Hill, whose Think and Grow Rich came out in 1937, to Stephen Covey, whose 7 Habits franchise still fills airport-bookstore shelves, to The Secret, the book and movie that partially restore those metaphysics, promising that the universe is governed by a law of attraction that returns our positive thoughts to us in the form of health and, especially, wealth.

Medical school takes a long time, but Carnegie’s book can be read in a night, and the Dale Carnegie Course it spawned, versions of which are still offered to individuals and corporations by a worldwide network of 2,700 instructors, can be finished in a weekend that promises to leave you “better-equipped to perform as a persuasive communicator, problem-solver and focused leader.” Learn how to put on the mask of someone who cares, to satisfy the longing for acknowledgment, and you can corner the market on friends and influence and, naturally, get rich in the process. You can even, as John D. Rockefeller Jr. (at least according to Carnegie) once did, end a miners’ strike simply by professing to understand and share common interests with the workers — a move that, Carnegie writes, “produced astonishing results . . . [T]he strikers went back to work without saying another word about the increase in wages for which they had fought so violently.”

Of course, as Watts points out, Rockefeller did not win the Great Coalfield War of 1914 merely by providing the strikers with an audience. After such standard union-busting techniques as mass firings failed to bring about the desired results, his Colorado Fuel and Iron Company obtained the services of Colorado’s National Guardsmen, who, along with company guards, turned a machine gun on a strikers’ encampment, killing something like twenty of its inhabitants. (Accounts vary, but we know for sure that the dead included eleven children and two women.) Another hundred or so were killed in the guerrilla war that broke out in subsequent days, which ended only after Woodrow Wilson sent in federal troops. Only then did Rockefeller arrive on the scene, preaching conciliation and cooperation and making various offers that the impoverished miners, with their busted union and diminished prospects, could not afford to refuse.

Carnegie’s “simplistic rendering of this traumatic event,” Watts writes, “epitomized a larger difficulty in How to Win Friends and Influence People: a startlingly naïve view of social, economic, and political issues that reduced them to matters of personality, human relations, and psychological adjustment.” But the view isn’t really all that startling, at least not to contemporary eyes — thanks in no small part to the success of Carnegie and all the self-help messiahs who have come in his wake, we’ve been led to think of all our troubles as manifestations of our inner lives. And to call it naïve may be to let Carnegie off too easily. He is, after all, the man who, having won friends and influence, used his newspaper column to tell his readers what he did when encountering people richer than himself.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. can’t enjoy a good book any more than I can; Andrew Mellon himself couldn’t see his wonderful collection of oil paintings with any better vision than mine . . . Yes, when I think of all the joys I can have at so little cost, I might, if I didn’t really enjoy my work and had no responsibility, even drop back and apply for a place on the relief roll.

This victim blaming seems just plain cruel, the platitudes of a man who has not simply forgotten his past but pushed it away with brutal force.

On the other hand, it’s no crueler than providing the downcast with an audience and then, once your attentions have gotten theirs, assuring them that because their suffering is not really the fault of the bankers and speculators who wrecked the economy, they have it within themselves to overcome it. It’s no crueler than telling them that what they lack isn’t money but the confidence that would render their penury inconsequential even as it makes their affluence more likely. It’s no crueler than turning empathy into advantage, and from there into a comfortable living. That’s what you want when you’ve been knocked to your knees, isn’t it? If not a god to beseech for a hand up, then at least someone who will tell you that you have what it takes, even if you are paying for the privilege.

Or maybe paying for the privilege is what makes it work. Attention purchased by the book or workshop or hour arouses desire. It is as if the listening apparatus springs to life when you drop a coin in the slot.

That’s exactly what Creflo Dollar has been telling the congregation that fills the 8,500-seat sanctuary of World Changers Church International in the Atlanta suburb of College Park. Seventy-five years after Carnegie’s book came out, in the midst of new hard times, Dollar paces the stage like a large and graceful cat. And he makes no bones about his success. “Ain’t nothing wrong with the preacher living the good life,” he says. “I ain’t changing. I’m gonna keep living the good life. Glory be to God!”

The life does seem good. He’s got a Gulfstream and a Rolls-Royce and a beautiful wife named Taffi. He cuts a handsome figure in his lustrous four-button suit, and his preacher’s voice is dulcet and buttery, nearly crooning. He still dabbles in old-time Pentecostal ecstasy, but these days when a brief fit of glossolalia overcomes him, he says, “Excuse me for that,” as if he has emitted a Holy Belch. And when, at the peak of his sermons (which you can watch on YouTube) — “Whoo! Glory to God!” — his eyes widen and he breaks into a victory cakewalk, it’s only a moment before he returns to the lectern, the holy roller giving way once again to the holy bankroller.

The World Dome, as he calls his church, cost nearly $18 million, of which Dollar borrowed none. (And yes, that is his real name. Unlike Carnegie’s father, Dollar’s, also Creflo, gave his son a name ready to use out of the box.) “God said we would build the church debt free,” he writes in The Holy Spirit, Your Financial Adviser. “The first thing He told us to do was dig a hole.” Sure enough, the money poured in. Dollar doesn’t explain exactly how that happened; his website says it was “a testament to the miracle-working power of God, and remains a model of debt-freedom that ministries all over the world emulate.” But when it comes to paying the bills, God generally needs some help from humans, and when Dollar says, “empower others and in doing so you will empower yourself,” his congregants know who those others are, and they know what the collection barrels at the doors of the sanctuary are for. He’s updated Carnegie’s advice; it’s no longer attention that has to be paid, but cash.

As Kate Bowler explains in Blessed: A History of the American Prosperity Gospel, the account of her sojourn among America’s prosperity churches, Dollar’s unabashed focus on the dollar is in direct keeping with the growing American religious tradition to which he is heir, and of which the World Dome is only one of many outposts. (Bowler, who visited a good number of what she calls prosperity megachurches, estimates their total domestic membership at around 750,000.) In the prosperity gospel, the call to tithe, Bowler explains, “eclipsed the sermon, worship, and communion as the emotional peak of the service, as pastors pushed their audiences to envision greater financial miracles.” Contributions to the church are like seeds sown in the money fields, and the good news is that you don’t have to count your blessings in spiritual currency or wait until after you die to receive them. “Abundance is on the way when you sow in good ground,” Dollar counsels in The Holy Spirit. So long as you “sow only where the Holy Spirit” instructs — “certain ministries, special projects, the lives of other Believers, and the life of your man or woman of God” — your harvest will come in, as his obviously has.

Bowler traces the origins of the prosperity gospel and arrives at the same place Watts does: the New Thought movement. Like Watts, she recognizes the significance of the nineteenth-century focus on individual initiative and the power of the mind. She points out that New Thought arose just after “the telegraph, electric light, and discoveries [that] demonstrated the role of germs in disease” introduced the American public to “invisible causal forces.” For Carnegie, those forces resided entirely in the unplumbed mind, but to the religious, they were located in a realm at once transcendent and immanent, a world in which physics was a subdivision of metaphysics, bodily health an outgrowth of spiritual health, and material wealth a divine blessing that God is eager to bestow. He’s ready to turn on the spigot just as soon as you do your part.

Mind power amplified by Christianity gives secular ministers like Carnegie a run for their money. After all, it’s one thing to learn in a Dale Carnegie Course or book how to put on the mask of a caring and confident person, and quite another to hear Joel Osteen, pastor of Houston’s 38,000-member Lakewood Church, assure you that you “have the DNA of Almighty God. You need to know that inside you flows the blood of a winner.”

The prosperity gospel arose in the late 1940s, when it was easy to believe that the tough-mindedness that had saved the world from Hitler and Tojo was attracting God’s blessing and leading Him to bestow the postwar boom on America. But it’s easier to believe that your blessing is just around the corner when the cash is flowing into your neighborhood than when the money is fleeing for gated communities. Unless, of course, the recent financial meltdown is even more apocalyptic than it seems, which is exactly what Dollar and his colleagues in the prosperity pulpit are preaching.

“The other day on the news, they said there’s a financial transfer going on,” he says. “But it’s a transfer from poor people to rich people. They don’t even know what’s going on.” What the news people don’t understand is that “God is setting this thing up.” Dollar explains: “The wicked rich have a call of God on their life to gather and to heap it up, and the scripture says it will be put together for the last days. Let me assure you, we are living in the last days!” Dollar doesn’t say why an omnipotent God needs the wealthy to concentrate the wealth, but he is sure that once they have finished doing this inadvertent favor, God will “reintroduce himself by putting the treasures of darkness into our hands.”

The World Changers probably know who those wicked rich are, but in case they don’t they could go to the Texas evangelist John Avanzini’s Millionaire University to learn that God intends to shower them with “the monies of the unsaved bankers, and the oil riches of the Arabs, and the money in the International Monetary Fund.” And while Avanzini promises an “army of saints” to facilitate the transfer, it’s pretty clear that revelation, not revolution, is going to redistribute the wealth. Believers will not have to occupy Wall Street; God is going to take care of that, and he’s not just going to bang drums in a park. But that doesn’t mean believers can sit back and wait for the money to rain down from heaven. “The Lord . . . is looking for a people he can trust,” the televangelist Benny Hinn advises. “We have got to get into position,” Dollar says.

For those unsure just which position to assume, offers for Dollar’s books and seminars crawl under his YouTubed sermons, in which he warns that “many voices right now are trying to speak concerning finances, and you need to know the voice of God.” In his book, the Holy Spirit’s financial advice sounds a little like your dad’s. He doesn’t want you to spend more than you make. He thinks you should have a budget. He expects you not to be lazy. He wants to help you “devise a successful business plan and operate a successful business.” He might wish for you to go to college, but whatever you do, you must not lose sight of “wisdom [that] gives us knowledge that is not found in the world.” And above all else, he advises, you should not borrow money. “You might not be in jail this morning, but you captive by debt!” he says. “There is a demon spirit behind debt,” he explains:

Satan says . . . “I got a plan. Here’s how I’m gonna stop the church of Jesus Christ. I’m gonna get everybody in the church in debt . . . I’m gonna build a wall of containment. I’m gonna contain them in one place, and I’m gonna use debt to do it. And every time . . . they get a raise, I’m gonna make sure I show them something else to spend it on . . . so the raise won’t really matter.”

These images are sure to carry special weight with the African Americans who make up the majority of his audience. But especially as they merge with the image of the small-business owner, graduate of the College of Hard Knocks, they speak to a grievance that transcends race, to thwarted dreams of liberty, to a middle class penned in by credit card debt and drowning in underwater homes.

If Dollar’s vision of end-time America seems on the mark — debtors on one side of a divide, money on the other, the two sides accelerating away from each other — his vision of the postapocalyptic life also seems familiar. “You are supermen and -women of God. You’re not Clark Kent. Don’t pray for enough,” he exhorts. “You’ve got to get into this realm of over and above. . . . Now establish this thought in your mind: There’s nothing wrong with me and my family living the good life.” If the American dream has become unattainable, if it requires an apocalypse to come true, it’s not because greed is bad. It’s because the wrong people have been occupying the realm of over and above and God is about to kick them out.

The righteous may have to wait a little while for that army of saints to expropriate the McMansions on their behalf. But they might not have to wait so long to be sprung from bondage, or so Dollar is telling them. “I have an announcement this morning. I have been anointed to preach this gospel to you today,” he says in one sermon. “I announce to all the World Changers,” he continues, cupping his hand around his mouth, “You are released from debt!” The crowd springs to its feet, arms raised and swaying.

Dollar knows exactly how to arouse desire in this crowd. He knows what has eaten into their confidence, and how to bolster it — and how to anticipate their resistance. “What I’m getting ready to tell you won’t make sense, but it will make faith,” he tells them just before announcing the “supernatural debt cancellation.” “I need some be-LEE-vers in the house! I need some people . . . that’s gonna take their master’s degree and just sit it down for just a little while.” And why shouldn’t they sit down their book learning? Dollar’s exhortation is surely demagoguery tailored to the desperate whose reason tells them their debts are insurmountable and whose only hope is for a miracle. But then again, they’ve recently witnessed exactly this kind of miracle, directed not by God but by presidents, and not toward the righteous but toward the unsaved bankers.

Dale Carnegie eventually softened his disparagement of religion. Watts tells us that in the early 1950s, just after he had published How to Stop Worrying and Start Living, Carnegie “returned to spiritual belief” — not because he had suddenly developed faith, but because he had “realiz[ed] its emotional utility . . . its therapeutic function.” He took to stopping in churches — any church would do — between lectures to chase away his tensions and anxieties. If religion was therapy for him, therapists, who had perfected the art of monetizing compassion, were in turn “modern evangelists . . . urging us to lead religious lives to avoid the hell-fires of this world — the hell-fires of stomach ulcers, angina pectoris, nervous breakdowns, and insanity.” Religion and psychotherapy, he recognized, both pivot on the placebo effect, the ability of the healer to relieve suffering through faith.

But even before Carnegie recanted his atheism, Sinclair Lewis grasped the self-help messiah’s peculiar religiosity. How to Win Friends, he wrote in 1937, was a “streamlined Bible” that made “Big Business safe for God, and vice-versa.” This sacred text of the entrepreneur told “people how to smile and bob and pretend to be interested in people’s hobbies precisely so that you may screw things out of them.” Compared with Dollar in this respect, Carnegie seems tame and reasonable, more George Babbitt than Elmer Gantry — and indeed, Watts tells us, Carnegie was not all that interested in his own balance sheets and was routinely fleeced by his own staff. His old-fashioned circumspection about money, disingenuous as it may be, is refreshing, if only because it softens the sociopathy of his advice.

Still, both Carnegie and Dollar are members of the American species perhaps first described by Herman Melville, who released his novel The Confidence-Man on April Fools’ Day in 1857, as the country was careering toward that year’s financial panic. Melville turns loose a man without qualities on a riverboat filled with the hopeful, the worried, the gullible. In a series of encounters, this man shows an expert ability to don and inhabit exactly the mask his mark wants to see. His confidence, as both Carnegie and Dollar might predict, conjures theirs, and always to their disadvantage. “Yes, there was a depression,” he tells a man who hesitates to buy a stock he’s heard has lost value. “But how came it? who devised it? The ‘bears,’ sir.” Bearish investors are to blame: “The depression of our stock was solely owing to the growling, the hypocritical growling, of the bears.” He gives the young man the good news he prefers to hear, winning his friendship and influencing him to empty his pocketbook.

Both Watts and Bowler understand that the empires they are reporting on are built on confidence, but neither author condemns the emperors as con men. Watts sees Carnegie as an avatar of American self-help, an ambiguous legacy, to be sure, but one that has helped “alleviate individual pathologies and private misery” and encouraged civility, even as it has contributed to the oft-lamented atomization, insincerity, and self-indulgence of modern life. Bowler, for her part, concludes that the

prosperity movement offers a comprehensive approach to the human condition. It sees men and women as creatures fallen, but not broken, and it shares with them a “gospel,” good news that will set them free from a multitude of oppressions.

If these authors don’t quite congratulate their subjects on their successes, they at least admire, if sometimes begrudgingly, their ability to capitalize on hope, to keep their flocks faithful in hard times to the one true American religion: optimism. And if Dollar is crasser than Carnegie, his promises more outlandish, it may only be because hope has become that much harder to keep alive. Each age presents its own desperation, but what may never vary is the opportunity troubled times create for flimflam.