Twenty-year-old Davonte Flennoy was killed on a Monday night in June 2012. As the setting for a murder, South Rockwell Street, in Chicago’s Marquette Park, was familiar enough to border on cliché. The last thing Flennoy saw as bullets entered his chest, arm, and head could have been the dumpsters artlessly ranked in the alley behind him or the razor wire curling atop a nearby chain-link fence. More than fifty other people had been shot throughout Chicago in the preceding ninety-six hours, ten of them fatally. Most of the shootings, and every one of the murders, occurred on streets like this one, in low-income neighborhoods on the city’s South Side.

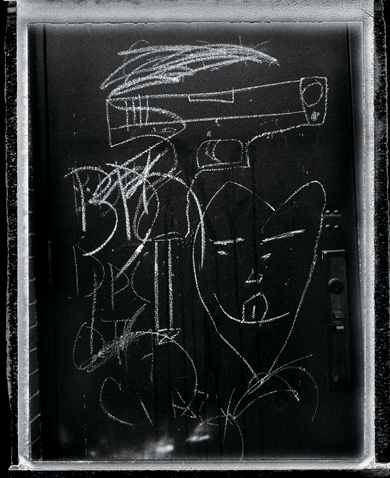

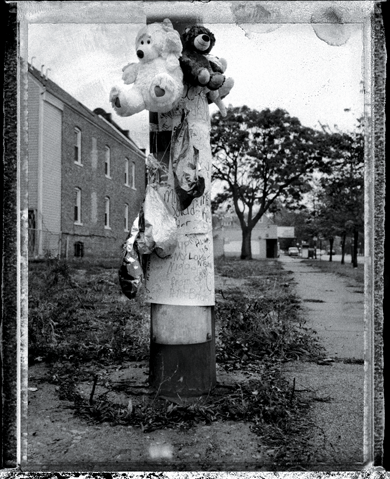

Memorial for a murder victim on 87th Street. All photographs from the ongoing series South Side © Jon Lowenstein/NOOR

That spring was a bloody one in the city, with homicides up nearly 35 percent over the year before. More than three fourths of the victims were black, most from a cluster of neighborhoods in the south and west: Englewood, Chicago Lawn, New City, Roseland. South Side activists feared the consistency of the crime reports might have a numbing effect, allowing people in the safer and whiter parts of town to tune out the distinctly personal tragedy of each shooting. On the day Flennoy was killed, dozens of activists had put on identical white T-shirts spattered with red paint, and nine of them had lain on the lawn outside St. Sabina church in the South Side neighborhood of Auburn Gresham. “These are not just statistics,” shouted Michael Pfleger, the church’s pastor, when NBC 5 showed up. “These are human beings.” They hoped to individualize the victims, but their matching costumes only seemed to underscore the anonymity of the body count.

In fact, the sort of cold statistics Pfleger decried had identified Flennoy as a special case worthy of hands-on intervention. Almost three years earlier, the Chicago public schools had launched a pioneering program to determine exactly which of their 400,000 students were most likely to get shot. Consultants from MIT and the University of Chicago developed algorithms to comb through archived information such as juvenile-detention reports, attendance records, and test scores, initially flagging more than 200 names. Flennoy was high on the list, deemed more than twenty times more likely than the average student to suffer a gunshot wound. For the next two years, the school district assigned him a mentor in an attempt to defy the odds.

The schools’ violence-reduction program had burned through most of its funding by the time Flennoy was shot, but the core idea has been adopted by another city institution. Early in 2013, the Chicago Police Department launched a pilot program that would use crime data to rank thousands of Chicagoans according to their chances of being involved as either victim or offender in a murder. In March, each of the city’s district commanders was handed a list of twenty names. It was a radical departure from traditional “hot spot” policing, which treats everyone in high-crime neighborhoods as potential victims or threats. Big data, already widely exploited in such fields as marketing and health care, had entered the territory of the beat cop. The case of Davonte Flennoy might suggest how powerful the new analytic techniques can be, but it should also serve as a warning that predicting a death isn’t the same as saving a life.

Chicago’s foray into victim prediction began in 2009, when President Obama appointed the city’s schools chief, Arne Duncan, to be his education secretary, and Mayor Richard M. Daley named thirty-seven-year-old Ron Huberman to replace him. Huberman, a former neighborhood cop, had helped oversee the creation of a system that sifted real-time data to identify evolving crime hot spots and supply officers with information on suspects, including aliases and gang affiliations. Touted by City Hall as the largest and most sophisticated police database in the nation, it won Chicago millions in grant money and Huberman his reputation as a number-cruncher with a political future.

This ex-cop with two master’s degrees walked into a school system with a well-publicized violence problem: at least 290 students would be shot by the end of the school year; thirty-four of them would die. Reports of violent incidents on school grounds were up 20 percent from 2008. Parents demanded action, and Huberman secured a federal stimulus grant, steering about $60 million over two years toward a new, data-driven violence-reduction strategy. Steven D. Levitt, the University of Chicago “rogue economist” who co-authored the best-selling Freakonomics books, was among those asked to help develop the predictive model. Levitt, who made his name by using data to tease out hidden correlations — most famously, he suggested that legalized abortion could be linked to lower crime rates — was intrigued by Huberman’s idea. Mathematical models had been used to calculate the probabilities of victimization before, but he’d never seen one applied to practical policy.

Using data provided by the school district and the police department, the economists considered basic variables such as race and gender alongside factors such as test scores. They found that their task amounted largely to quantifying common knowledge. Gender was the most important predictor: 97 percent of the students on the list were male. Another significant variable was the historical per capita shooting rate of the school where the student was enrolled. Having spent time in a juvenile-detention center increased a student’s likelihood of being shot by 2.5 percentage points. Although black and Hispanic students dominated the list — only one of the 232 originally picked for the program was white — the economists determined that race itself was statistically insignificant as a predictor in this population. What mattered more than being black was having poor grades. “You don’t need a statistical model to know that if you identify those kids, they are at high risk,” Levitt said. “The models help quantify some of those effects, but they aren’t magical and they certainly are no crystal ball.”

Even to some of his friends, Flennoy didn’t seem much different from the other sophomores at Gage Park High School in 2009. “I didn’t really think of him as being high-risk, per se,” recalls Star Wells, who dated him throughout high school and is the mother of his son, Davonte Jr. “Friends he’d hang around with got him involved in not-so-good situations, but he wasn’t like a ‘gang member.’ ” In fact, Flennoy sometimes projected an image of someone who went out of his way to avoid trouble. That year, he published his first and only op-ed in the student newspaper, complaining that gangs on the South Side were setting “a bad example for the younger children” and that encouraging students to go to college might help combat street violence. Public image aside, here are some of the salient factors that put Flennoy near the top of the at-risk list during his sophomore year: he missed more than ninety days of school, his father was serving a five-year prison sentence on a federal drug charge, his name regularly showed up in reports of interpersonal conflicts on the school grounds, and he was a year older than most of the other students in his grade.

Two of Flennoy’s best friends were on the list as well. Freshman Dimonte Pryor and sophomore Brandon Harris — half brothers who see that term as too weak to describe their fraternal bond — had known Flennoy since 2007, when they met playing basketball next to Flennoy’s house. In middle school, the three friends developed a shared interest in Chicago footwork, a fast-paced style of hip-hop dance. At house parties and shopping malls they’d circle up with rival squads and one of their guys would shuffle to the center, skating and kicking to rhythms that pulsed upwards of 150 beats per minute. Girls watched. Adrenaline flowed. Sometimes the scene escalated into a fight. Shortly after Flennoy, Harrison, and Pryor began high school together, their group — now about thirty members — began to call itself Rec City.

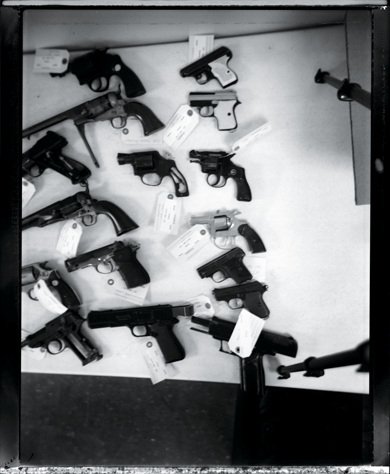

The name didn’t mean anything in particular, but its suggestion of urban recreation seemed appropriate at first. In high school, however, the group’s focus shifted from footwork to self-defense. Two of Harris’s friends got into a fight with another circle of students, many of whom Harris had known since elementary school, who began calling themselves Hit Squad. Photos from those early days show the members of Rec City in sparsely furnished apartments, holding plastic cups and smiling, their arms around each other or their girlfriends. But one shows Pryor standing outside in a doorway, his left hand flashing the Rec City hand sign, his right clutching a .38 Special. Around the same time, Flennoy began to carry a 9mm.

When the school district’s analysis identified the three friends as high-risk, they were assigned to the same mentor, a forty-year-old Baptist minister named Stevie Powell. Every morning for two years, Powell picked the boys up and drove them to school. The program found after-school jobs for all three students, and Powell made sure they reported to work on time. Sometimes he and his wife would go on a double date with one of the boys and his girlfriend, taking the younger couple out to a bowling alley or a movie. He arranged for Flennoy, Harris, and Pryor to be transferred to alternative high schools for students who had failed in traditional classroom settings.

In 2011, the designers of the school’s prediction model published a report assessing the program’s effectiveness. Comparing the ultra-high-risk students who had received mentoring during the first year with another high-risk group of students outside the program, they found the rates of gunshot victimization to be about the same in both groups. But the number of students receiving mentoring was so small that such comparisons were statistically meaningless. “Despite a large and intensive effort,” the report concluded, “there is little evidence of improved educational outcomes and insufficient power to evaluate the impact on shootings.”

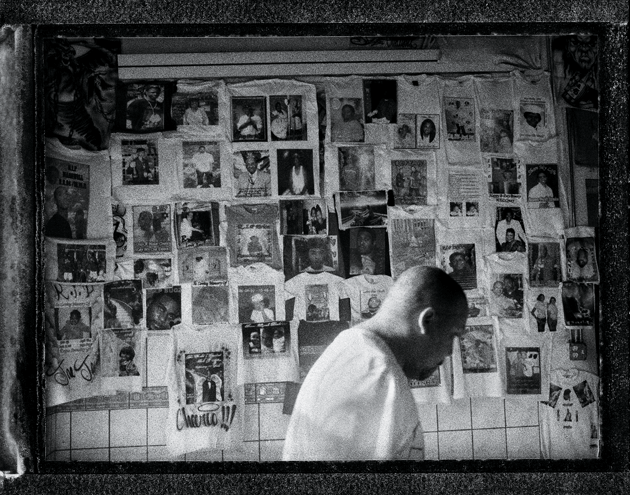

Friends and relatives of Starkeisha Reed outside her Englewood home in March 2006. Reed, aged fourteen, was shot in her living room as she was preparing to leave for school

As the mentorship program faced funding cuts, the Chicago Tribune reported on Powell’s work with the students, describing Flennoy opening up to a men’s group in a local church about his experiences of violence and his responsibilities to his son. Behind Flennoy’s bravado, Powell saw something quiet and kind, a young man with good intentions and bad role models. He challenged him to stop playacting the thug and be the idealist who’d written the op-ed, who sometimes dreamed aloud about going to college. Flennoy became one of the program’s success stories — he’d been on track to flunk out of school but was now preparing to graduate.

Powell lobbied program administrators, college admissions officers, a state representative — anyone who might be able to help send Flennoy to a college somewhere outside Chicago. The Tribune article helped persuade the school program’s administrators to fund an “exploratory visit” to Atlanta Metropolitan State College in Georgia, where Flennoy’s grandmother lived. Powell spent a week pleading with the college’s recruiter to overlook Flennoy’s spotty academic record and unimpressive test scores. “Mr. Powell, I have never done for a student what I am doing for Davonte,” Powell remembered the recruiter saying. “But I can tell this is something special. We’re gonna make this work.” Powell raised several thousand dollars in donations from friends, church members, and community leaders to rent Flennoy a studio apartment near campus. In August 2011, he drove Flennoy to Midway Airport and put him on a Georgia-bound plane.

Most homicides in Chicago are gang-related, and the police department’s interest in predictive analytics is partly a response to an evolving gang landscape. In the 1980s and 1990s, vast stretches of the city were dominated by “nations,” several with tens of thousands of members. People who lived in neighborhoods ruled by the Gangster Disciples or the Vice Lords, for example, often knew the gang leaders by name. But when, in the mid-1990s, federal authorities started locking up the kingpins on drug and conspiracy charges, the organizational hierarchies collapsed. Entry-level gang recruits had less incentive to fall into line. Younger kids started forming their own cliques or factions. Chicago’s annual murder rate dropped from around 900 in the early 1990s to an average of 458 between 2004 and 2011. But then, in 2012, the numbers started to rise again.

By the first week of that spring, the city had marked its hundredth homicide of the year, and its murder rate was defying a long downward trend in other major American cities. It had been an unusually mild winter, drawing more people out onto the streets, but police superintendent Garry McCarthy discouraged his colleagues from blaming something so ungovernable as the weather. Instead, he sometimes spoke of permissive gun regulations in neighboring states and weak sentencing laws in his own. Narcotics agents accused the Mexican cartels of inflaming drug-related violence. The police union blamed a staffing shortage. All was fodder for internal debate, but everyone seemed to agree that the killing was mostly connected to street gangs, and that those gangs had changed. Police have estimated that 625 gangs now exist in Chicago, some with only a handful of members, others with several hundred (three people is enough for a group to be considered a “gang,” according to the U.S. Department of Justice and the Chicago City Council). The estimate is based on traditional crime reports and also on “gang audits,” informational sessions at which police work with neighborhood residents to connect specific crimes with specific factions and create detailed maps marking territories and disputes.

The audits were initiated in 2010 with the help of Andrew Papachristos, a young sociologist at Yale who has a long personal history with the sorts of criminals the audits try to identify. In 1992, as a fifteen-year-old on Chicago’s North Side, Papachristos watched his parents, who owned a local restaurant, refuse to buckle under extortion threats from a neighborhood gang. He began to go on regular anticrime foot patrols with the Guardian Angels. After the gang burned down his parents’ restaurant, he developed a lasting obsession with figuring out how gangs work. Papachristos has analyzed two Chicago communities — West Garfield Park and North Lawndale — that together saw 191 homicides during a recent five-year span, a rate more than three times that of the city as a whole. Simply by using arrest records to identify links between individuals in those neighborhoods, he mapped a social network that consisted of about 4 percent of the neighborhoods’ populations, among whom about 40 percent of the homicides occurred.

At criminology seminars, Papachristos illustrates his social-network analysis using an overhead projector. He displays two dots, which represent two men arrested for gun possession. The dots touch each other, because the men were arrested together. More dots appear, symbolizing more arrests made over time. Eventually, as more individuals are implicated in crimes together, dense clusters of dots begin to take shape. Links, both direct and indirect, can be seen within the easily defined clusters. “What you don’t see in this picture — and remember this is Chicago — you don’t see a hierarchy,” Papachristos explained during a 2011 seminar in New York City. “You don’t see a ‘corporate’ gang.” The clusters represent relatively small criminal groups with little division of labor and few distinctions between the types of illegal activity performed by their members.

In 2012, police had noticed that the names of a couple of factions were popping up with stunning frequency when they questioned witnesses at crime scenes. In one of the deadliest South Side police districts — Chicago Lawn — homicides had already jumped 156 percent by July, while many other districts had experienced little or no increase. That October, police would attribute the neighborhood’s rising murder rate, which they said was skewing crime data citywide, to a conflict between two factions in Chicago Lawn and Englewood: Hit Squad and Rec City. In the press, the police described Rec City as a faction of the Gangster Disciples, which wasn’t technically correct. Although some pledged a loose allegiance to that gang, others claimed kinship with the Black P Stone Rangers or the Black Disciples. Some didn’t identify with any other gang at all. The group had formed around a core cluster of a half dozen friends who liked to dance.

A week after Flennoy got to Atlanta, while he was struggling through placement exams, a seventeen-year-old girl named Charinez Jefferson was shot in the head, chest, and back near her apartment in Englewood. The building where she lived sits well inside Rec City’s declared territory, which occupies eight square blocks on the South Side. West 63rd Street — a busy artery of check-cashing shops, coin laundries, cell phone stores, and Mexican restaurants — cuts through the middle of it. The side streets are lined with brick, bungalow-style houses built for the middle class in the 1920s, then abandoned to a mostly struggling underclass in the 1960s. It’s easy to see examples of what comes across as a heroic sort of residential pride: ceramic reindeer ornamenting snow-covered lawns in the winter, replaced by birdbaths and tidy rock gardens in the summer. But boarded-up windows in run-down apartment complexes aren’t hard to find, either.

Jefferson lived in one of those complexes, just off a corner on 64th Street where a police surveillance camera is mounted high on a streetlight. If any Rec City members ever needed refuge, from either the police or a rival clique, she’d open the doors of her building to them. Today, members of the group tell stories about how they’d lie low in the halls of her building, sometimes dozens of them at once. She went out with a good friend of Flennoy’s. Witnesses told police that she had begged her killer to spare her, revealing to him that she was eight months pregnant. An eighteen-year-old with ties to Hit Squad was arrested. Doctors delivered Jefferson’s baby, but the boy had suffered permanent brain damage. He survives in a vegetative state on life support, cared for by his grandmother.

When news reached Flennoy in Atlanta that Jefferson had died, he broke down in tears. He blamed himself, telling his grandmother that Jefferson wouldn’t have been killed if he hadn’t left Chicago. He called Powell and said he couldn’t go through with college, and his old mentor tried unsuccessfully to talk him out of coming home. After returning to Chicago by bus, he quickly fell in with his old friends. He told Star Wells he felt he had let people down. In the nine months that followed, she noticed that he didn’t talk much about Atlanta.

At about 10:40 p.m. on the night of June 11, 2012, Flennoy called Wells to tell her that he was coming over. “Stay woke,” she remembers him saying, “I’m gonna stay the night at your house.” About forty-five minutes later, Flennoy’s mother called Wells to tell her he’d been shot. The alley where his body lay was four blocks outside Rec City’s territory, less than one block from the residence of the Hit Squad member who’d been charged in Jefferson’s killing. Police found a 9mm under Flennoy’s body. The story that eventually emerged on the streets was one of mistaken identity: Flennoy and a couple of friends had fired shots in the direction of a group of men, believing them to be Hit Squad members. When Flennoy realized that they were not who he had thought, he tried to apologize. One of Flennoy’s companions yelled something and ran off, prompting retaliatory fire and leaving Flennoy exposed. To date, no one has been arrested for his killing.

At the funeral, Flennoy was dressed in his best gray suit. The printed programs handed out at the door honored his intelligence, kindness, and talents, which existed “in spite of the overwhelming odds and statistics so heavily stacked against him.” Friends from Rec City pressed tightly into the large chapel, helping to pack it beyond its capacity of nearly a thousand people. According to the general principles of social-network theory, they faced a greater risk of being gunshot victims themselves, simply by being part of that crowd.

The CPD’s predictive-analytics formula is being developed directly across Interstate 94 from U.S. Cellular Field, home of the White Sox. In a glassy and light-filled research building at the Illinois Institute of Technology, you’ll find pharmaceutical logos in the lobby and offices with brain scans projected on high-definition screens. Everything inside feels clean and well-funded — a clinically pristine counterpoint to the rowdy disarray of a metropolitan police station. Here, Miles Wernick is leading the team of engineers that builds the tools behind the police department’s “hot list.”

Wernick, the head of IIT’s Medical Imaging Research Center, also co-founded a company that designs programs to help diagnose the existence and severity of cognitive diseases such as Alzheimer’s. Criminology was foreign territory to him before he applied for a $3 million grant from the National Institute of Justice (the R&D arm of the Justice Department) to partner with the Chicago police. But Wernick realized that the same technology used to seek patterns within a person’s medical data could be applied to crime data. Instead of combing through the information embedded in brain scans and biochemical tests, he’s now mining the country’s richest metropolitan-crime database, sorting through years’ worth of incident maps and arrest logs.

As with the predictive model developed for the schools, one of his algorithms generates a list of individuals ranked according to their likelihood of being involved in a particular crime, in this case homicide. The first list that Wernick’s model produced, in March 2013, included 17,207 names, all people who had appeared in Chicago’s criminal database during the preceding five years. Those near the top of the list were estimated to be at least 500 times as likely as the average Chicagoan to be either the victim or the perpetrator of a homicide. Those near the bottom were judged about 17 percent likelier than average to murder or be murdered.

Unlike the school system’s model, the police’s version searches for evidence of social connections between the high-risk individuals themselves and factors those connections in as additional risk, along with other aspects of a person’s criminal record. The city’s crime database can reveal interpersonal relationships in a few different ways. Known gang affiliations cited in police reports can establish direct links. Additionally, about one third of all arrests involve more than one alleged offender, and those co-arrests reveal connections between thousands of people. Using such information, the computer model can calculate indirect contacts to four degrees of separation. When a person is linked by co-arrests to lots of high-risk people, his or her own risk increases.

If there’s anything that’s guaranteed to annoy a beat cop, it’s being told by someone who is not a beat cop how to police his domain. When the CPD’s district commanders were handed the names generated by the computer model, eyes rolled. “We got some resistance from the field,” said Steve Caluris, the Chicago police commander tasked with applying the data analysis on a practical level. “They’re looking at Joe, Steve, and Tom as guys who are out there, guys that they know and want to target. And all of a sudden we’re giving them a couple different names. And they’re like, ‘These aren’t the guys that we do.’ ”

A lot of rank-and-file cops believe that figuring out who’s likely to be involved in a homicide isn’t too difficult. What’s tricky is stopping the crime. “I’ve yet to see a computer make an arrest,” says Pat Camden, who became a Chicago cop in 1970 and is now spokesman for the union that represents the city’s officers and detectives. Camden notes that Mayor Rahm Emanuel, shortly after taking office in 2011, cut about 1,400 unfilled police-officer positions from the city budget. The kind of proactive legwork that a hot list demands is impossible, he says, when the city tries to cut costs by investing in computers instead of personnel. “If I know you’re a bad guy and I don’t have time to look for you,” Camden says, “it doesn’t do me any good.”

During the first half of 2013, murders in Chicago dropped almost 35 percent compared with 2012, but the police would not, or could not, provide a specific example of how the probability scale had been applied to deter crime during that time. In July, the department announced that one of its district commanders had begun dropping off letters at the residences of the individuals on their hot lists, letting them know that they had been singled out. The police department and its technical partners speak of the predictive model as a modest first step, emphasizing that it might eventually be paired with counseling or job-hunting assistance. Wernick would also like to see the police’s tools used in ways that are more similar to the schools’. “There’s a social-services side to this,” he told me.

But the schools’ strategy of assigning mentors to high-risk students cost about $15,000 annually per student — an untenable expense for a cash-strapped police department. Even if such a direct prevention strategy were affordable, the schools’ experience still hasn’t provided much evidence that it would be worth it. Backers of the program make the reasonable point that Flennoy might have been shot even sooner had he not participated in the program, and that during the years he was mentored he turned his academic trajectory around. That’s a significant achievement in itself, but the goal of the program was to save lives.

“When you look at a geographic map and it says, ‘Here’s a hot spot on the corner of 63rd and Knox,’ you know what to do,” Papachristos explained. “You send police cars to that area to deter crime or cool things down. But when you say, ‘This is a group of people who are in a really high-risk social network,’ it’s not clear exactly how to interpret that for policing.” Putting someone on a hot list, Papachristos pointed out, is far simpler than getting someone off of one. “That this kid came back from Atlanta after his friend was shot is really, really telling about how strong that social network was.”

About six months after I first met with Dimonte Pryor and Brandon Harris about their friend’s murder, I picked up Pryor outside a convenience store on 63rd Street to talk about what he’d been doing to avoid sharing Flennoy’s fate. The neighborhood crawled with police cars; we passed three spaced about a block apart along 63rd Street. Each car was angled to the curb, and each had a young man with his hands on the hood, assuming the position. As I drove, Pryor placed a call to a friend, and together they strategized about a drug test Pryor was scheduled to take the next day as part of a court appearance. A few weeks earlier, police had found heroin on him. It was the second time in four months he’d been arrested for possession with intent.

I’d spent a lot of time listening to Pryor tell me how important he believes it is to maintain self-control and focus when trying to survive on the South Side, and I’d often wondered why he keeps getting picked up. When I asked him what he thought about the fact that drug dealing increased his risk of getting shot, he let out a long breath. “That’s how I make money,” he said, almost whispering. “It’s how I live.” Compared with the old corporate-style gangs, Rec City’s dealing is small-time and provisional. But it keeps Pryor in trouble with the law. The district cops, he said, know him well: “Basically, I’m a guy whose name is just ringing.” The more I pressed him about his choices, the more fatalistic he got. “Whatever’s gonna happen to you’s gonna happen to you,” he said. “Whether they catch up with you now, whether they catch up with you later, whether they catch up with you ten years from now.”

Pryor’s brother Harris sees things differently. He told me that he didn’t tolerate that sort of resignation. At twenty-two, he is a year older than Pryor, and if anyone can be considered the founder of Rec City, it’s him. We met each other for the first time in a downtown diner for breakfast. About an hour into the conversation, I asked whether he feared his past in Rec City might catch up with him. He wasn’t concerned, he said; he knew how to carry himself on the streets, how to avoid danger when things got hot, and he’d recently distanced himself from Rec City, moving out of the old neighborhood into an apartment a couple miles away. He was the father of a one-year-old girl, and he now considered himself a “neutron”: someone who’d left the core of the clique and wasn’t involved in the conflict with Hit Squad. “It’s easy to walk away,” he told me. “I walked away a lot of times after I did stuff. Like the other day, I thought about my daughter. Every action now, I think about my daughter.”

About ten minutes later, however, after the conversation moved on to new topics, he began to look uncomfortable, physically uneasy. Harris is a big guy, a linebacker in high school, whose nickname, “Six-Four,” was given to him before he’d stopped growing. I thought maybe he felt cramped in the tight booth, but, as he explained, that wasn’t why he’d shifted his bulk uncomfortably on the bench. Just weeks before, he’d been shot.

Harris had been visiting his aunt, who lives within Hit Squad’s territory. He knew showing his face outside at night would be asking for trouble, so he waited until the next morning to go home. At about seven a.m., he walked out the door and down 67th Street. A couple of blocks later, he heard someone shout, “That’s Six-Four!” He was near an alley when he saw someone running at him. “In their mentality,” he told me, “they think I’m still on that — think I’m probably still a gangbanger.”

He darted toward an iron fence separating the alley from the back yard of one of the neighborhood bungalows, hoping to run through the gate and cut between two properties. The gate was locked. As he climbed the fence and prepared to vault himself over the sharp points of the decorative finials, a bullet tore into his thigh, just under his buttocks. Before he hit the ground on the other side, a second bullet hit his inner thigh.

Over the next few months, that close call seemed to motivate him to distance himself even further from life in the clique. He’d worked in maintenance for the city’s parks departments the previous summer, and he was determined to get a full-time job. He took a test to get licensed as a security guard, and he passed. No security jobs came his way, but he continued to apply for any openings he could find, particularly those that might take him out of his neighborhood. Eventually he found work at a Walmart on the North Side.

In late December, on the day Davonte Flennoy would have turned twenty-one, Harris told me that Rec City was throwing a party. “It’s gonna be packed,” he predicted. “Probably like eighty people.” It was more like 200, crowded into a cleared-out beauty salon. Many wore T-shirts silk-screened with pictures of Flennoy. Others wore photos of a friend they called Delorean, whose life was also being celebrated in remembrance of his “death day.” Harris arrived at about ten p.m. He and Pryor mixed with the crowd, sipping Hennessy, Flennoy’s favorite drink. Within a couple of hours, the police arrived and broke up the party, but it moved to a house and lasted almost until dawn. Harris rekindled his friendship with some of the guys who had come up with him in the clique. Some had recently become fathers. Others had been in and out of jail. “When we had to leave,” Harris told me later, “we tell everyone we loved them. I ain’t never said that before. But I want to see them all again.” He left wearing one of the T-shirts with Flennoy’s picture on it. Printed on the front were the words rec city for life.