“My daughter, she have a big problem,” Easy Mzikhona Nofemela told me one day on the phone, his voice panicked.

“What kind of big problem?”

“She have terrible pain in her tooth.”

“Do you need a ride to the dentist?”

During the more than two years I spent in Gugulethu, a black township on the outskirts of Cape Town, I was asked for money repeatedly, but with time, fewer people bothered. I once gave a lift to a man who deduced that I was American, inspected my ten-year-old Renault hatchback, and then asked, puzzled, “But where is your Ferrari?” Easy had never asked me for a penny, though he was essentially broke — his modest salary tied up in high-interest cash loans, an exorbitant funeral-coverage plan, a small fund for his daughter’s education, and membership in a service that provided a lawyer in an emergency — and he had never asked for a favor. But he accepted help if I offered.

I met Easy while researching the murder of a white American Fulbright Scholar named Amy Biehl in Gugulethu in 1993, during the waning days of apartheid. Easy and three other young men had been tried and convicted of Biehl’s murder and sentenced to eighteen years in prison. But in 1997, Easy and his co-accused appeared before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, South Africa’s experiment in restorative justice. Chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, it offered release and amnesty to those who could prove that their apartheid-era crimes had been politically motivated.

Easy, then a skinny twenty-six-year-old with Coke-bottle prison-issue glasses and enormous white high-tops, sat before the commission and read from a statement carefully crafted by his attorneys, arguing that he had been incited by leaders of the student wing of his party — the Pan-Africanist Congress, or PAC — who had chanted “One settler, one bullet” at a morning rally, a slogan he’d taken as a direct order. He and his comrades, he said, had been marching down the street when Amy Biehl, in a case of bad timing, drove by to drop off three colleagues. Easy and his co-accused were granted amnesty in 1998 and freed in 1999. After his release, he had apologized to and built a relationship with Biehl’s parents, and he now works as a driver at an NGO they established in her name that provides after-school programs for kids throughout Cape Town’s townships.

The next morning, I left the beige stucco cottage I was renting in Sea Point, a wealthy suburb ten minutes from the city center on a sliver of land by the Atlantic Ocean. Though Sea Point has always been de facto a white area, in 1953 it was officially designated as such by the apartheid government, and it remains predominantly white today. The neighborhood’s streets are narrow and swept clean by a tired army of brown-skinned contract workers in neon vests stamped with the phrase jesus saves. Most homes are hidden from view by walls lined with electric fencing, glass shards, or barbed wire. From my kitchen table, on clear days, when I opened the iron security gate to get a nice view, I could watch paragliders jumping from the peak of Lion’s Head behind me and floating down to a lush rugby field near the promenade at the water’s edge.

To get to Gugulethu, I took the N2, a fifteen-minute straight shot out of town, past Table Mountain and District Six, a once multicultural neighborhood that was designated a whites-only area in 1966 by the apartheid government; removals of non-whites began in 1968 and proceeded in waves well into the 1970s, and many of the old homes and buildings were razed. I drove past the defunct power plant and its persistent stink, the tangled trees and marsh reeds lining the highway. I turned off at the Duinefontein exit, where workhorses grazed on patches of dirty grass at the border of Bonteheuwel, a gang-ridden and poor neighborhood of coloreds, as the generally Afrikaans-speaking mixed-race population is called. I drove past the Shoprite, a windowless brick building where public toilets are padlocked to the walls and guards armed with machine guns alternately stand watch and help old ladies work the bread slicer. Then I took the highway overpass that separates Gugs, as the area is affectionately called, from the rest of the world.

Gugulethu is an apartheid invention, made possible by the passage in 1950 of the Group Areas Act, which aimed to forcibly separate each of the four official South African racial classifications into its own living area. (Apartheid means “apartness” in Afrikaans.) In Cape Town, whites, for the most part, inherited the beautiful city center, the leafiest suburbs, and the ocean views; colored people were placed in square government “matchbox houses” in bleak zones like Bonteheuwel, Manenberg, and Mitchell’s Plain, all of which neighbor Gugulethu. Tens of thousands more were moved to so-called green fields on Cape Town’s periphery, where they survived by fashioning shacks of corrugated tin. Nearby, rows of drab single-room homes had been constructed to house “bachelor” men whose purpose was to provide labor to whites. Gugulethu was established in 1962 to absorb the population overflowing from the older townships of Langa and Nyanga. It was originally called Gugulethu Emergency Camp. Gugulethu means “Our Pride” in Xhosa.

The architects of apartheid dreamed of complete racial segregation. “The Native should only be allowed to enter urban areas, which are essentially the white man’s creation, when he is willing to enter and minister to the needs of the white man, and should depart therefrom when he ceases so to minister,” declared the prescient Stallard Commission in 1921. Although colonial powers had for centuries been dividing South Africa along racial lines, a policy of discrimination was officially sanctioned by D. F. Malan, the National Party prime minister, who was voted into office by an almost entirely white electorate in 1948. The infamous Natives Land Act of 1913 had limited black ownership of land to 7 percent of South Africa’s territory (a figure increased two decades later to around 13 percent), but after 1948 a series of discriminatory laws and practices were instituted to further dispossess black people, relocating more than 2 million of them to ten bantustans, or “homelands” — underdeveloped rural reserves led by black puppet chiefs.

Unlike other parts of the country, Cape Town and its province, the Western Cape, boasted a significant colored population, and the National Party hoped that they could provide all required labor, thereby rendering black workers unnecessary. But the colored population did not satisfy the growing needs of industry. And few black families could survive in their derelict new homelands. Many soon left, trekking hundreds of miles to Cape Town, building shanties and trolling the streets for work, legal or otherwise. In 1959, there were 72,711 black people in Cape Town; in 1975, despite the government’s best efforts, there were a reported 100,530 — in addition to squatters, whose numbers went largely unreported.

Today, nearly two decades after the end of apartheid, nearly 1.5 million black people live in Cape Town, the majority of them in townships. Gugulethu’s population of 98,468 remains almost entirely black. Most residents are ethnic Xhosa. Many are Christian, but township inhabitants have also revamped old, rural traditions to suit their lives. For example, a young man must spend several weeks in the bush in an elaborate rite of passage involving circumcision, though “the bush” in Gugulethu is an overgrown roadside plot next to a pork wholesaler and a cash-and-carry. Gugulethu also houses a small number of somewhat unwelcome refugees and asylum seekers from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Malawi, Somalia, and Zimbabwe.

Easy’s house, on NY 111 — NY stands for Native Yard, the lingering apartheid demarcation for most township streets — is situated near a row of witch doctors and barbershops that operate out of shipping containers. It was originally a rectangular three-room house set back from the sidewalk, but it has been extended in all directions; an overhang made of uneven concrete blocks reaches the edge of the street, and a series of rooms press against the far end of the back yard. The home is a block from the local garbage pile, fed on by goats, mutts, and wandering beggars.

When I collected Easy to go to the dentist, his elderly neighbor, an elegant woman with close-cropped gray hair, was dancing loosely in the street, smashed at eleven a.m. She had lost all five of her sons to, variously, a police shoot-out, a gang shoot-out, a bar stabbing, AIDS, and an unspecified illness. Easy’s father, Wowo, was, as usual, fiddling with his rusted Nissan pickup in the open garage. He used to get so full of rage that his family sometimes slept outside to escape his temper, but these days he is friendly, philosophical, and calm. In 2005, after thirty years of working in the gardens of a multinational insurance company, during which he never made more than $550 a month, Wowo received a onetime pension payment of $9,500, which he used to build the sagging overhang and buy a white Ford Sapphire sedan. The household now boasted two old cars, but nobody had money for gas, so everyone walked or took public transportation.

I passed through the entryway into the main room, stuffed with ornamental furniture that Easy’s mother, Kiki, had inherited from her employers when she was a domestic worker: three spiffy love seats protected by white cotton covers and decorated with handmade doilies, a heavy oak dining-room table pushed into a corner, a surplus of high-backed chairs. On one wall, an unwieldy plastic shelving unit displayed an untouched stuffed toy dog, a photograph of the three white children Kiki had helped raise, and two huge speakers that were connected to a TV in another room and played booming, disembodied sounds all day. I peeked into the TV room, where Easy sat wearing a pressed gray button-down and gray trousers. He is a compact, boyish forty-two-year-old with a hearty laugh, a collection of gang and prison tattoos on his arms, and a face covered in small, dark scars — from a knife fight, a stick fight, a car and a taxi accident, and a scorned ex-girlfriend with long nails and a vendetta. He was watching a Nigerian soap opera.

“My precious friend!” he exclaimed.

Kiki, seated on an upholstered chair, stared at me dispassionately. She is a short woman with a youthful face, her hair always tied up in a cloth. She is deliberately fat, since in Xhosa culture fat on an old lady is a mark of dignity and a large family. “Hello, Makhulu,” I said, addressing her as “Grandmother,” a sign of respect. Despite herself, Kiki broke into an amused smile and nodded. Plus, my car was useful today, because we had to pick up Easy’s daughter, Aphiwe, from school.

Easy and I got in the car and followed NY 111, passing the one house with the pretty front garden and the old company hostels now taken over by squatters. During apartheid, companies housed black migrant laborers from the homelands in single-sex dormitory-like structures, carting them to and from manual jobs each day and allowing them one month a year to visit their families. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as apartheid edged toward its demise and the townships became increasingly ungovernable, the companies abandoned these buildings and the workers and their families took over. Twenty years later, they still live in cramped, deteriorating quarters under faded signs bearing the names of the original owners: wjm construction corp, ume steel ltd, dairybelle pty. Pigeons roost in the broken shower stalls. Once in a while, a police tow truck pulls out from a hostel’s courtyard, dragging a stolen car behind it.

We drove to Gugulethu’s main road, recently renamed Steve Biko Drive — after the founder of the black-consciousness movement, who was tortured to death by apartheid forces in 1977 — but still widely referred to by its old name, NY 1. We headed past the bodegas, the stands selling barbecued sheep’s heads, the herbalist who could help with “weak erection, early ejaculation, court cases, lost lovers, blood pressure, ETC.” We passed a man who stood on his front lawn dressed as a sensei. “You get the energy, and that gives you the power,” he pronounced in the direction of a dirt patch.

“He is training his students in karate,” Easy told me.

“Where are they?”

“He can see them,” Easy said, “but we cannot.”

We pulled up to Aphiwe’s government school, a group of squat structures arranged around a spotless interior courtyard. According to the elderly principal, who strolled around in a long skirt, the entire school, with 250 children, received $3,500 annually for all expenses, including electricity for the classrooms. The walls were covered with faded murals. A charity had once donated thirty bulky computers but had neglected to arrange funding for security or cooling, and the principal had been saddled with a storage room full of easily stolen PCs; she eventually persuaded the German Embassy to provide an alarm system and an air conditioner. She showed me a computer lab full of nine-year-olds; most of them were eating sticky, crumbly snacks and jumping up and down under a handwritten sign directing no eating + running around. They were being watched over by a pair of diligent fourteen-year-old girls.

“The teacher is out sick today,” the principal explained brightly.

“She joking,” Easy told me later. “The teacher get a new job and leave and they don’t have a replacement.”

Easy asked a kid loitering in the courtyard to find his daughter, and moments later nine-year-old Aphiwe appeared in the parking area in her navy-and-yellow uniform and heavily scuffed black Mary Janes. Her brown hair is in perpetual disarray, since Easy, for whom Aphiwe is the center of the universe, has mastered neither the art of braiding nor that of routine. Aphiwe’s mother had her at nineteen but left Easy’s house when Aphiwe was two years old and took her child away to the privacy and freedom of her sister’s shack. One morning while visiting before work, Easy found Aphiwe alone with only an eight-year-old cousin. He picked her up and brought her back to his house, where he kept her close to his bare chest, “like the kangaroo.”

As in many cultures, Xhosa children are discouraged from questioning their elders, so Aphiwe didn’t ask about this expedition. She sat in the back of the car and played with my ponytail, as was her habit. We arrived at the health clinic in the next township, Khayelitsha, where hundreds of black people sat on rows of wooden benches. Many middle-class and wealthy South Africans consider free care at a government hospital to range from useless (a routine checkup) to a potential death sentence (surgery). For the poor, obtaining such care is a full-time job.

“You get there at nine and you leave at five,” a pregnant woman explained to me. Whenever she had a prenatal checkup, she left the house at six a.m. to begin queueing. If she was lucky, she’d be home by three.

Easy’s uncle was friends with the dentist and could speed the process along, so we were ushered to a back room, where a group of women sat chattering loudly. Aphiwe perched gamely on a plastic chair and ate a hot-dog-and-mustard sandwich that Kiki had packed for her.

When the dentist called Aphiwe, Easy led us into a spartan room. Aphiwe lay down stiffly in the chair, her toothpick legs outstretched. In a matter of seconds, the dentist, a bald black man in a polo shirt, held out his hand, and the nurse, a heavyset woman in wire-rimmed glasses, handed him an enormous hypodermic needle. The dentist squirted novocaine into the air once and then, swiftly propping Aphiwe’s mouth open with his hand, began to insert the huge needle into her gum. Her tiny body tightened immediately and she let out a desperate, shocked screech, then closed her mouth as tears began to stream down her cheeks.

Easy lowered his face close to his daughter. “Vula, Aphiwe!” he ordered. Open, Aphiwe! “Vula, vula, vula!”

As her mouth opened a centimeter, the dentist jammed the needle in and pulled it out. She went limp. Easy lifted his daughter up and hauled her away, past the ladies chatting in the waiting room. A little boy looked suspiciously at his grandmother.

Easy deposited Aphiwe on a square of concrete outside and watched as she heaved on her hands and knees. A couple of patients went in and out. Then it was Aphiwe’s turn again. Easy dragged her back to the room, where she lay in the chair. Her face slick with tears, she opened her mouth as the dentist requested.

Suddenly, he reached in with a pair of heavy steel pliers and ripped her molar from her gum. For a split second the room froze and the dentist stood still, brandishing the tooth high above his head. Then Aphiwe let out a full-throated wail and bolted from the room. She flew into the waiting room and flung herself onto a chair and then to the floor, where she let out a series of loud, brokenhearted moans and spat out a stream of blood. The ladies scooted their chairs away. Easy lifted Aphiwe by the shoulders, stuffed some gauze in her mouth, wrapped her school sweater across her chest to stop the blood from further staining her yellow shirt, and marched out of the clinic. We covered the back seat of my car with newspapers and put Aphiwe there, where she sat, whimpering, for fifteen minutes, her arm flung across her eyes.

“Oh, my baby,” Easy said, his voice wavering, looking at Aphiwe in the rearview mirror. “My poor angel.”

In South Africa today, people like to joke that your résumé can be blank but for one qualification and you will still become a minister or a tycoon: you need only have served time at Robben Island — Cape Town’s offshore prison, where Nelson Mandela and other political prisoners suffered for decades — and your future will be bright and certain.

In 1994, after three centuries of colonial oppression and forty-six years of apartheid, Mandela became South Africa’s first black president in its first all-inclusive democratic elections. Today, Mandela’s party, the African National Congress, or ANC, still wins two thirds of votes cast.

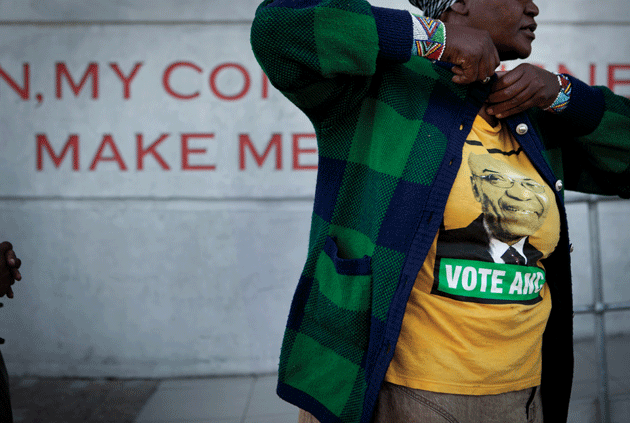

“Zuma is drying up our funds, our taxes, fucking up the country,” said an intoxicated retired teacher wearing an oversize peacoat. We were standing in a two-room concrete house in an informal settlement near where Easy lives. The house, set among illegal shacks built on a municipal plot, belonged to Easy’s aunt, a factory worker who had lost her husband to a heart attack and her favorite son to alcoholism and now invited everyone to get drunk at her place so she would have company. The teacher was referring to the current South African president, Jacob Zuma, an ANC–Robben Island graduate. Recently, $20 million of public funds was spent upgrading Zuma’s private estate in a poor rural village. A leaked draft of the public protector’s report found that Zuma had derived “substantial” private benefits from the upgrades to his residence. A report by Zuma’s ministers claimed that the improvements were merely security measures: what appeared to be a new swimming pool was in fact a “fire pool,” since there were no fire stations in the area, and the structure that the press had misunderstood to be an amphitheater was simply “a structure with steps.” Zuma was cleared of all charges.

“I vote for ANC because only one movement liberate us,” the teacher said, swaying. “But Zuma can go to hell in a nutshell.” (This sentiment was reflected at the Johannesburg memorial service for Nelson Mandela this past December, at which Zuma’s speech was roundly booed.)

In Gugulethu, many people believe that the most efficient path to riches is to get deep into the ANC; that way, you can get a government job or contract, a pretty house subsidized by the government, and possibly a nice car as some sort of bribe or kickback. One of Zuma’s cabinet members spent about $36,000 of taxpayer money to visit a lover jailed in Switzerland on drug charges. Former police commissioner and Interpol president Jackie Selebi was found guilty of corruption and of taking bribes from a drug dealer; his successor, Bheki Cele, was dismissed amid allegations that he mishandled a $160 million building lease. People are enraged, but they also want a piece of the pie. For most, however, it is twenty years too late to make such connections, and they cannot revise their role during the Struggle.

Unlike many township residents, who wept and marched in memory of Mandela, Easy and his neighbors watched the endless coverage of the former president’s death with little interest and even less emotion; Mandela was not their man. NY 111 and its surrounding streets were once a PAC stronghold. But after splintering off from the ANC in 1959, soon after the party declared itself multiracial, the PAC began to operate under the charismatic leadership of its founder, Robert Sobukwe, a socialist who in 1963 was sentenced, under what came to be called the “Sobukwe clause,” to indefinite detention on Robben Island. He was kept in isolation for six years, separated from his PAC loyalists and from Mandela, before he was allowed to return home under house arrest and died, in 1978, of lung cancer that went untreated for weeks while he applied for permission to go to a Johannesburg hospital.

Sobukwe and his acolytes believed that African land must be returned to the African people. The radical armed wing of the PAC, the Azanian People’s Liberation Army, or APLA, became infamous for trying to destabilize the country by attacking white civilian establishments. The party currently allows white members, though few people of any color wish to join. The PAC now holds a single seat in Parliament, over which its shrinking contingent constantly battles.

NY 111 and the neighboring areas are today shared among average working-class people, ex-militants, ex-combatants, and gangsters, both active and retired. Some former gangsters, hoping for glory and military benefits, claim to be ex-freedom fighters, though few admit to having at some point belonged to a gang. One Gugulethu resident, now an armed security guard for a bank, claimed political ignorance and then told me, his voice hushed, “If my employer knows what I did then, I can be fired today.” Meanwhile, some people who were politically ignorant in the old days today claim “struggle cred.” Former PAC militants, for the most part, suspect that they chose the wrong party back then, and believe that if they had been arrested for attending ANC instead of PAC rallies, they would have better jobs today, though of course plenty of ANC members live in poverty in shantytowns across the country.

If you jump over Easy’s back fence, you’ll land in the yard of an ex-militant named Mzwabantu “Mzi” Noji, who was an APLA soldier in the 1980s and 1990s. Easy and Mzi aren’t exactly friends but something perhaps more intimate: They are of these blocks, NY 111 leading into NY 119. They know the unspoken rules of the neighborhood and the township, and they know each other’s life stories. Easy knows, for example, that Mzi was recruited by APLA as a teenager and spent his twenty-third year in prison on weapons charges after an all-night shoot-out between APLA cadres and apartheid government forces in 1993. When Mandela was elected the following year, Mzi was sleeping in a cell that guards flooded at night as a form of torture. In 1996, a year after his release, he was integrated into the newly created South African National Defense Force, in which white apartheid-era soldiers served next to, and sometimes under, the men of color they had formerly oppressed.

Mzi is slender, with light skin and an upturned nose, deep-set black eyes, and a slightly misshapen head, the result of a long-ago mob attack by ANC members. He keeps two photographs in his room: in one, from 1991, he is a nineteen-year-old freedom fighter dressed in camouflage, sitting on a mound of red earth surrounded by dry brush, pointing an assault rifle into the distance. The other picture is a poster-size photo of a tank set against the black night, emblazoned with the words 3 sa infantry battalion. In the upper right corner is an image of a twenty-seven-year-old Mzi in state-issued military fatigues, a black beret superimposed on the dark background. His flat expression is unforgiving.

By 2000, Mzi was back in prison, this time serving five years of a seven-year sentence for a robbery he says was pinned on him. After getting into a fight with another prisoner, Mzi was sent to solitary confinement. In his cell, he found a book called Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening. He had always been a loner interested in world religions, and in any case meat made his teeth hurt. He became a Buddhist and a vegetarian and spent the last two years of his incarceration meditating and gardening. He kept a slim, meticulous manila folder filled with papers commemorating his various prison accomplishments: a high-school diploma, two “Mindfulness Awareness in Action” courses, a prize as the best medium-security inmate in the fight against HIV/AIDS, and an award of merit for outstanding performance in an 800-meter track event. While in prison, Mzi had also renounced violence, a fact he did not advertise in Gugulethu. Recently, he suspected a kid named Kenya of stealing his nylon car cover. When Mzi confronted Kenya, Kenya threatened Mzi.

“I’m a diehard. I’ll never let some boy get me,” Mzi said. We were sitting at a Wimpy Burger and he was drinking orange juice, not the milkshake he wanted, because he was “feeling fat.”

“But what about renouncing violence?” I asked.

“That’s the thing!” he said, throwing his hands in the air.

Violence is nearly impossible to escape in Gugulethu, where residents often have to fight, physically, for respect and survival. Men battle other men to protect the very women and children they then pummel with their own fists. Fights between couples sometimes take place in public, with women swinging back. In a shebeen — the township term for a tavern — a friendly argument can devolve into a knife fight, and a small slight directed toward the wrong guy can get you killed.

When I visited Mzi one morning last April, he was wiping blood from the previous night’s stabbing off the floor of the Spirit Horse, as he has christened his immaculate old turquoise Toyota. At around ten p.m. the night before, a distant relative of Mzi’s named Nishno, who lived down the road, hurled himself over Mzi’s high iron fence and landed on the brick stoop, calling out for help, his chest and stomach punctured nine times.

“Hayi, hayi, hayi!” Nishno was yelling. No, no, no. He was a twenty-three-year-old who spent his days smoking tik, a form of crystal meth. Tik, inhaled from a miniature lightbulb connected to a straw, makes you emaciated and wild, as evidenced by the bands of young addicts strutting through the area, followed by old addicts limping alone down the streets. It also rots your teeth.

Nishno had retained his good looks, his strong, straight nose, and all his crooked teeth. He had, however, succumbed to another side effect of tik use, which was stealing. The previous afternoon, Nishno had been at the pale-yellow single-level house he shared with his extended family. In the back yard, hanging on the wash line, he found two pairs of men’s trousers, which he plucked off the line and sold for three dollars at the squatter camp a few roads away. Those pants belonged to the boyfriend of Nishno’s twenty-one-year-old niece, who did not take the loss lightly. The boyfriend waited for Nishno to emerge from a nearby shack, where he had been watching TV, and then stabbed him with a switchblade. Bleeding, Nishno broke free and ran down the street to Mzi’s small family compound.

Mzi and his brother each live in single-room lean-tos in the back yard, while their mother, four of her grandchildren, and one of the adult sisters live in the main two-bedroom house. On the night of Nishno’s stabbing, Mzi’s brother, who abided by a personal policy of non-interference, peered out briefly at the commotion unfolding on his lawn and then retired to his room. But Mzi was concerned about a new mob-justice movement gaining popularity in the townships, where terrified or incompetent police have long been unwilling or unable to prevent black-on-black violence. During apartheid, police forces were feared as tools of a racist state. They raided the townships and routinely tortured prisoners, sending them home blind, deaf, or mad; some people disappeared entirely after a run-in with the cops. Today, twenty years after Mandela’s election, most of the police are black or colored, but they are sometimes just as brutal. In August 2012, at a platinum mine near the town of Marikana, in the country’s North West province, police forces killed thirty-four striking miners, most of whom were shot in the back, and injured at least seventy-eight others. In February 2013, in Daveyton, outside Johannesburg, cops tied a Mozambican taxi driver to a police van and dragged him to his death as a stunned crowd tried to intervene. But crime committed among locals remains endemic: between 2003 and 2011, an average of 143 murders a year were reported in Gugulethu, a rate more than thirty times New York City’s. In 2012, there were 106 attempted murders, 257 sexual assaults and rapes, and 454 home burglaries — and these are only the official numbers in a country where many crimes go unreported. Vigilante-administered punishment is usually disproportionate and vicious, and it is sometimes mistakenly directed at innocent people, but it satisfies a communal need to see wrongdoers face consequences.

Mzi had recently embarked on a campaign to keep NY 111 and NY 119 clear of the all-black neighborhood watch groups — according to Mzi, made up of “thugs, rogue government guys, vigilantes, and cops” — that now roam the dirt paths of settlements at night, bearing sjamboks — long whips made famous by apartheid police — which they use to punish anyone out after an 8:30 p.m. curfew, including people returning from work. He had visited nearby communities, bearing a laminated newspaper article describing a mob murder in Khayelitsha during which a watch group had severely beaten an alleged young robber and then locked him in a portable toilet, which the group doused with gasoline and set alight. The article, entitled deathcrap, included photos of the dead man’s dismantled shack below a photo of his ash-encrusted corpse. No arrests had been made. Mzi wanted to avoid such a gruesome scene on his streets. What if they’d gotten the wrong man?

With this concern in mind, Mzi got out of bed and approached the gate. Nishno’s assailants were surrounded by women and children from the shacks and hostels down the road, demanding that Nishno be ejected onto the street. They didn’t have much, and boys like him were always grabbing their phones, their shoes, even their furniture. Let him walk home and face the consequences of stealing! Thieves must be punished!

“Sorry, bhuti,” Mzi said to a man with a switchblade, addressing him as “brother” in Xhosa, as was standard. “But I cannot allow you to kill this boy.”

The crowd protested.

“Hayi, bhuti, you don’t know the whole story!” they yelled.

“I don’t want to know,” Mzi said softly. “Go to your homes.”

Some of them swore at him, but, sensing that he could not be persuaded, they all eventually left, and nobody held a grudge the next day.

“Why were they cross with you?” I asked. “Did they want justice served, as they saw it?”

“No, they didn’t want justice,” Mzi explained, shaking his head. “They have become accustomed to violence. To them, it is like watching a live movie. They were angry because I ended the movie before the end.”

When Mzi was finished polishing his car, we drove to a township hospital. The night before, Mzi had driven Nishno — wrapped in three garbage bags and two blankets to protect the car’s houndstooth interior — to the emergency room, and Nishno’s mother had asked that Mzi now check in on him. We walked into a chilly waiting area lined with cracked plastic benches. A small girl lay listlessly on a seat, holding a plum. We passed a security booth and entered a large, windowless space filled with sick and wounded people on beds, and we found Nishno in the middle, shirtless, covered in bandages, a tube pulling fluid from the slash near his left nipple. He looked small and impossibly young. He wore an oxygen mask and was asking the doctor if he could have some food.

The doctor, a chubby bespectacled white man in his early thirties, was bent over a table piled high with bloody gauze. He was from Ohio, as it turned out, fresh out of med school and on a monthlong volunteer stint in the Cape Town townships before beginning his job at a hospital in Delaware. He was telling Nishno to breathe, even though it was painful, and that he could eat after his X-ray.

“So is it very violent here?” I asked.

“Very,” he said, smiling pleasantly but looking as if he was about to burst into tears. “This isn’t the first time I’ve seen multiple stab wounds like this.”

“How long have you been here?” I asked.

“Two days.”

In 2010, a honeymooning European couple, apparently on a tour of the “real South Africa,” were driven through Gugulethu at night. Their taxi was hijacked at gunpoint, and the husband, a British national of Indian origin named Shrien Dewani, was pushed onto the street. His bride, a Swedish-born twenty-eight-year-old named Anni Dewani, was found dead in the abandoned taxi the next morning in Khayelitsha. She had been beaten and shot. The tabloids widely described Anni as “beautiful” and Gugulethu, variously, as “dangerous,” “notorious,” and “notoriously dangerous.” Investigating authorities soon came to suspect that Shrien had put a hit out on Anni. British courts ordered his extradition to South Africa, but Shrien’s lawyers, who claim he is mentally ill, are currently asking for the decision to be blocked until he is fit to stand trial. “He thought it was like, come to South Africa, hire a hit man,” a detective directly involved in the case and who wished to remain anonymous told me.

Despite the political transformations in South Africa and the process of national reconciliation, the Dewani murder, like the killing, seventeen years earlier, of Amy Biehl, confirmed the fears of many whites. My first months in South Africa were spent primarily with a wealthy group of white people who lived in heavily secured houses by the sea. Few had ever been to a township, and many were scared to even drive near the places. I was warned not to come down with “Amy Biehl syndrome,” in which white do-gooders who work in the townships forget how vulnerable they are. Although these privileged folks claimed never to have actively supported the apartheid regime, they remained nostalgic for the order and efficiency of that tightly run state in which nobody was stealing the sinks out of the public hospitals and what was out of sight was out of mind.

White citizens packed stadiums around the country to celebrate Mandela as their great president and to mourn his passing. But their everyday lives usually reveal neither an attempt at integration nor an understanding of the lasting effects of apartheid. In Cape Town, brown-skinned maids and gardeners appear from the ether and disappear as effortlessly, and a successful black person is often viewed as either an exception to the laws of nature or a well-connected beneficiary of affirmative action. The searing inequality of the city — its organized bands of vagrants picking through the garbage of the rich on trash-collection mornings, its sidewalk vendors and glue-sniffing kids milling in the streets next to luxury-car dealerships — is a fact of quotidian life, a nuisance at best and a danger at worst.

“I don’t know why they won’t come here,” Mzi said, annoyed. “We forgave them already.”

Among other things, Mzi hoped that whites would come into Gugulethu and bring money. Since he left prison, he had not held a job for very long. He had applied without success to be a paramedic, a truck driver, and a cell-phone salesman. Now he spent his days volunteering for the waning PAC, attempting to gain benefits and jobs for APLA veterans who had fought for a free South Africa and who now had nothing to show for it. But he was also a certified “excursion facilitator,” or tour guide, who dreamed of charging fifty dollars a person to tell his history of South Africa. Easy also gave tours, as he was ordered to do by his NGO employer; the organization, with its international connections, hosted a steady stream of moneyed visitors. But working on his own, Mzi couldn’t snag many clients.

“How does he do it?” he muttered when he saw the one white socialist who lived in Gugulethu leading a line of Europeans in khaki shorts and highs socks down the street. “Because he is white,” he concluded without malice.

When Mzi did get clients, which happened rarely and usually through word of mouth, he led them through what he called “the journey of remembrance,” which ran from District Six to Gugulethu, stopping at the memorial to seven anti-apartheid fighters killed by armed forces in an ambush in 1986, and at a high marble cross dedicated to Amy Biehl, against which an old man and his collection of mutts snoozed.

Mzi had named his tour company the Social Nexus Consultancy, which he suspected was not catchy, and he didn’t feel confident marketing his business in the hotels and tourist centers downtown. The black diamonds, as young, upwardly mobile black South African professionals are called, can confidently walk into luxury stores and chic restaurants. But for people who are somehow marked as township dwellers, those parts of the city are an exclusive club at which they are not welcome.

Mzi and I once had quiche and cappuccinos at a spacious coffee shop near Parliament, and when I went to pay the bill at the counter, Mzi stepped outside. Within moments, a black Zimbabwean waiter approached him.

“Are you looking for something?” the waiter asked.

“Why?” Mzi asked.

“My boss wants me to ask you to move away.” Inside the restaurant, a colored woman in an apron averted her eyes. Nearby, white hipsters loitered, absently staring at their iPhones or smoking.

Mzi leaned toward the waiter. “Listen here, my brother,” he said. “You are an African from outside of South Africa and I am an African from South Africa.”

Mzi extended his hand and the waiter, stricken, took it.

“You remember apartheid but you won’t know apartheid,” Mzi continued, beginning the long-form African handshake: the Western grip, followed by a clasping of each other’s thumbs, back to Western grip. Then he held on loosely as the waiter’s eyes widened. “Tell your boss I fought for this land and I have the right to be wherever I want. I respect all Africans, who have a right to be anywhere in Africa, and I ask that you also adopt this attitude.”

The waiter mumbled several thank-yous and walked slowly inside, where he sat down at a table, deflated.

“Verwoerd was brilliant, an inventor of the future,” Mzi said as we walked away. He was speaking of the former prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd, an uncompromising proponent of apartheid, who was assassinated by a mentally ill mixed-race parliamentary messenger in 1966. “He still rules from the grave, that guy. The waiter must be happy I am a Buddhist.”

Mzi was considering renaming his company Shanti Tours, shanti being a Sanskrit word for “peace.” He was trying to come up with ways he might improve traffic. I thought of Easy, who gave tours to a constant flow of visitors. According to Easy, township residents by now understood the quirks of white tourists, which Easy summarized as “they take pictures, they like dogs.” But most of all, according to Easy, tourists loved kids — and the kids of Gugulethu were generally gregarious with visitors, hamming it up gleefully as soon as a camera appeared. Whenever possible, Easy led tourists to an after-school program, where the hastily assembled children would dance or sing traditional songs as smiling white people recorded their every move. If the kids were in the middle of a class, they stopped their lesson and gathered for photo opportunities.

“Maybe if you add kids to the mix?” I suggested to Mzi. “Maybe tourists like the touch of hope that kids radiate.”

“You think I am too serious?” he asked. He had recently been campaigning to get a group of perpetually unemployed ex-combatants, some of whom hadn’t had a full night’s sleep in decades, back into trauma therapy. Years earlier, he had helped the same group undergo counseling at a nonprofit center, but the program fell apart when the young female therapist appointed to the group told her boss that she was terrified of the dark, war-torn men with scarred faces and gruesome stories.

“You’re pretty serious,” I said. On one of Mzi’s recent tours, an American woman cried quietly on three separate occasions.

“Well, I can organize kids to play instruments, but I will have to bribe them,” he said.

All tours of Gugulethu have one thing in common: they end at Mzoli Ngcawuzele’s self-named restaurant on NY 115. Mzoli’s, Gugulethu’s most famous establishment, is an elaborate barbecue joint. Outside, sidewalk industries have sprung up, including a car wash (two men with a bucket and dish soap) and a souvenir stand (a table displaying ashtrays made from beer-bottle caps). Dozens of strung-out men in dusty neon-yellow vests stand in the streets, hoping to usher drivers into parking spaces for a few rand. The line for food runs through a room empty except for three deli cases: two full of raw meat in plastic tubs, and one full of steaming pap — a maize porridge used to sop up sauce — and a spicy, finely chopped salad of tomatoes, onions, and bell peppers called chakalaka. Mzoli’s wife, a commanding, maternal woman, works the cash register. Once customers buy their raw meat, they carry it to a sweltering back room where a collection of soot-covered cooks rub it with spices and roast it over an open fire in a pitch-black oven.

One afternoon, Easy and I were sitting at a table as pouring rain hit the clear tarps surrounding the dining area. A group of chubby black men sat nearby, surrounded by bottles of top-shelf liquor and a platter of sausages. They had to be, Easy suspected, government employees or drug dealers or office managers to afford that kind of alcohol. Maybe some of them even lived in the suburbs — people with enough money could always move out of the townships and into more contained neighborhoods, but when they grew homesick, they headed for Mzoli’s. At another table, two young mothers holding babies on their laps were tucking into a platter of chicken and sharing a can of ginger soda. A white man and a Latin man, both dressed in neat button-downs, stared at us from the next table over. The white man leaned in.

“Is the food okay to eat?” he asked.

He was British, it turned out, and his companion was Bolivian. They were in Cape Town on business — though the nature of that business was not revealed.

“But is it safe here?” he asked. “Didn’t that English lady get killed here?”

We stayed for an hour. Our meat was delivered, along with pap and chakalaka, on a large metal plate, no utensils. More people strolled in, and the noise level rose. Easy’s new wife, Tiny, stopped by after her long day as a debt collector and planted a generous kiss on his cheek before heading home. A group of colored professionals had left work early and driven into Gugulethu with coolers full of beer. A half dozen local women in high heels carted in fruit-flavored wine coolers and ordered four platters of chicken and lamb. An elderly white American woman with her family requested a bottle of chilled white wine; her guide returned from the bar next door with twist-top chardonnay balanced on a pile of ice in a cardboard box lined with a trash bag. She happily poured herself a glass.

When three large women in sparkling red dresses sidled onto the restaurant’s makeshift stage, ready to perform, Easy and I left and drove back to his house. Kiki stood out front holding some money. She needed fish for dinner, and as long as my car was there, Kiki would use it. A cockroach taxi — the rusty jalopies that roam the blocks — cost $1.50 round-trip within Gugulethu’s borders, and occasionally they’re stolen by tsotsis (township gangsters), who pick up passengers only to rob them. Aphiwe, who had been playing with her cousins, flew into the back seat, and we drove across the township to Gugulethu Square, a sprawling modern complex of banks, chain stores, fast-food shops, and pharmacies that Mzoli and his partners developed in 2009. Across from the mall, a line of people extended from a bedraggled pickup truck manned by a fisherman. Easy hopped out and sprinted across two lanes of traffic.

Aphiwe and I sat in silence. She moved close to me, studied my face, put a strand of my hair beneath her nose. She smelled like gummy bears.

“What is your favorite food?” I asked.

“Pizza,” she said softly.

“Plain?”

“With mushrooms.”

Easy was across the street in a crisp white T-shirt, wearing a new brown cap he’d bought for two dollars because a street vendor told him he looked winning in it. We watched him chatting exuberantly with the people in line.

“What is your favorite thing about your dad?” I asked.

Aphiwe thought for a while. Then she pressed her mouth to my ear.

“Pride,” she whispered.

Easy came back with a dripping package of fish. Aphiwe helped him wrap it in a plastic bag. Then we drove back toward NY 111.

We drove by Mzi’s house, where a group of teenage boys were pushing his car out of the driveway. The engine had died. Mzi steered, his brainy eight-year-old niece sitting in the back, clutching her toddler cousin, a child so round and beatific he had been nicknamed Buddha.

“M’Africa,” Easy said, addressing Mzi as “African.” Easy was no longer involved in politics, but in the right context he used the old honorific for comrades. “From Cape to Cairo, Morocco to Madagascar.”

“Izwe lethu,” Mzi said. The land is ours.

We continued past the squatter camp whose residents had called for Nishno’s punishment and past the old ironworkers’ hostel. Raw sewage streamed out of the building and collected in puddles in the street. A few feet away, a well-coiffed woman was hanging her washing to dry. We pulled up to Easy’s house and said our goodbyes. Easy stood on the pavement, watching me leave. I maneuvered around a broken-down car and back over the bridge, then onto the N2. When I was nearly home, the ocean came into view on my right and bright-green Lion’s Head peak rose before me. At my exit, the gardens on the street medians were carefully manicured.

“But the strange thing is, when I leave Gugulethu, I miss it,” I once said to Mzi as we sat in a square of sun on his lawn. We had been discussing politics, history, and the challenges faced by the townships and their residents in this twenty-year-old new South Africa.

“Yah,” he said, looking around, his face relaxed. “It is a lovely place.”