Discussed in this essay:

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, by Elizabeth Kolbert. Henry Holt. 352 pages. $28.

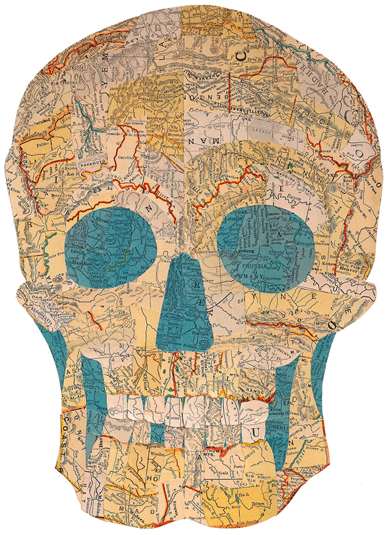

The extinction symbol is a spare graphic that began to appear on London walls and sidewalks a couple of years ago. It has since become popular enough as an emblem of protest that people display it at environmental rallies. Others tattoo it on their arms. The symbol consists of two triangles inscribed within a circle, like so:

“The triangles represent an hourglass; the circle represents Earth; the symbol as a whole represents, according to a popular Twitter feed devoted to its dissemination (@extinctsymbol, 19.2K followers), “the rapidly accelerating collapse of global biodiversity” — what scientists refer to alternately as the Holocene extinction, the Anthropocene extinction, and (with somewhat more circumspection) the sixth mass extinction.

It’s always been a difficult planet. About 4 billion species have emerged since the place became habitable, 3.5 billion years ago. Ninety-nine percent of those species no longer exist. But five times in prehistory things went truly pear-shaped for the living. All schoolchildren know about one of these events, not only because it wiped out almost every dinosaur unlucky enough to be wingless but also because it did so by way of a flaming rock the size of Staten Island, which slammed into the Yucatán Peninsula at a speed of about 45,000 miles per hour. The impact vaporized everything in what is now North America, caused continent-reshaping tsunamis, released enough dust into the atmosphere to block out the light of the sun, and turned the oceans into a sulfuric stew for millions of years.

This was the most dramatic of what even the hardest-nosed academic journals tag as the Big Five. It wasn’t the worst. That distinction goes to the so-called end-Permian event, which took place about 252 million years ago. No one knows exactly what happened then, other than that the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere spiked, pushing up global temperatures and upending the chemical composition of the oceans. Warmer oceans may also have led to the flourishing of bacteria that produce hydrogen sulfide, a substance that, to put it mildly, most life-forms don’t find hospitable. Ninety-six percent of all species disappeared. The end-Permian event has been called the mother of mass extinctions. It has also been called the Great Dying.

These are justifiably sensational terms — but they perhaps give a mistaken impression of the speed with which mass extinctions take place. A giant asteroid is exceptional: the dinosaurs may have died out in a matter of months. The other events happened on a geologic timescale, grinding away slowly at the planet. The end-Permian played out over more than 100,000 years. The extinction event that wiped out the trilobites, at the end of the Ordovician period, and the one that wiped out the giant reptiles, at the end of the Triassic, played out over millions.

For most observers, scientific and otherwise, speed is a defining feature of our present-day extinction crisis, which is happening at such a rate that we — a species with a current average life span of sixty-seven years — are able to notice it happening. All across the planet, in every ecosystem, on every landmass and in every body of water, plants, animals, and microorganisms are now dying out within decades rather than millennia. The International Union for Conservation of Nature, a Switzerland-based organization that monitors the conservation status of more than 71,000 species, lists nearly 30 percent of them as threatened. “It is estimated,” writes Elizabeth Kolbert in The Sixth Extinction, her thorough and fascinating new book, “that one-third of all reef-building corals, a third of all freshwater mollusks, a third of all sharks and rays, a quarter of all mammals, a fifth of all reptiles, and a sixth of all birds are headed toward oblivion.” The widely agreed-upon benchmark for a mass-extinction event is a loss of 75 percent of the planet’s biomass. We’re not there yet, but we’re on our way. According to Anthony Barnosky, a geologist at the University of California, Berkeley, if the IUCN’s assessment can be taken as a guide to the future — and few doubt that it can, unless extraordinary political and economic measures are taken — the Big Five could become the Big Six by as early as 2400 a.d.

What does this planetary denuding look like in real time? The extinction symbol’s Twitter feed gives us some hint.

Honeybee decline decisively linked to pesticide use

Dugong population in Indonesia being decimated by industrial pollution

Gorillas and chimps are threatened by human disease.

Overfishing causes Pacific bluefin tuna numbers to drop 96%

Iceland to kill endangered fin whales for dog food.

West Africa’s last rainforest, an area 50% bigger than Wales has been sold off to logging companies.

Plankton heading for extinction due to climate change, and this could trigger the collapse of entire ecosystems

China’s Last Wild Indochinese Tiger Killed and Eaten By A Villager

And so it goes, 3,600 dispatches and counting from an ailing biosphere. To read the feed from beginning to end is a stupefying experience, like going through the records from some vast terminal ward. But as with almost all nontechnical writing on extinction, that isn’t the spirit in which the feed is intended. The purpose isn’t documentary. This is a cri de coeur — an indictment for mass murder against a very familiar defendant. A post on April 22, 2012, encapsulates the tone of the project by way of a quotation attributed to Albert Schweitzer and used by Rachel Carson in her dedication to Silent Spring: “Man has lost the capacity to foresee and to forestall. He will end by destroying the earth.”

The Sixth Extinction is not nearly so prophetic in tone. For more than a decade, Elizabeth Kolbert has covered the ecological-degradation beat for The New Yorker, where some of this book has previously appeared. Her reporting is meticulous, her prose restrained, her humor infrequent and respectful, her chapters foursquare. Beneath the velvet glove, however, there points the familiar prosecutorial finger.

Kolbert begins coyly, with a kind of fairy tale. “Maybe two hundred thousand years ago,” a new species emerges on Earth. Compared with other species around at the time — mammoths, mastodons, armadillos the size of Smart cars, an animal paleontologists refer to as the “demon duck of doom” — the members of this new species aren’t very fast or very strong. But they’re shrewd, or reckless, or both. “None of the usual constraints of habitat or geography seem to check them,” she writes. They start out in a small section of eastern Africa. There’s water there, and plenty to eat. But are they satisfied?

They cross rivers, plateaus, mountain ranges. In coastal regions, they gather shellfish; farther inland, they hunt mammals. Everywhere they settle, they adapt and innovate. On reaching Europe, they encounter creatures very much like themselves, but stockier and probably brawnier, who have been living on the continent far longer. They interbreed with these creatures and then, by one means or another, kill them off.

And there you have it, on page two: consume, screw, kill. The Homo sapiens way. By the time this tale has ended, a few paragraphs later, humans have blanketed the globe; slaughtered and/or eaten all the flashy megafauna; humped their numbers into the billions; chopped down the forests; spread disease and rats (and diseased rats); discovered coal and oil; and caused global warming. It’s like the gag in the sequel to Airplane! —

And there you have it, on page two: consume, screw, kill. The Homo sapiens way. By the time this tale has ended, a few paragraphs later, humans have blanketed the globe; slaughtered and/or eaten all the flashy megafauna; humped their numbers into the billions; chopped down the forests; spread disease and rats (and diseased rats); discovered coal and oil; and caused global warming. It’s like the gag in the sequel to Airplane! —

mccroskey: Jacobs, I want to know absolutely everything that’s happened up till now.

jacobs: Well, let’s see. First the earth cooled. And then the dinosaurs came, but they got too big and fat, so they all died and turned into oil. And then the Arabs came and they bought Mercedes-Benzes

— only, of course, not funny.

What follows, often in great detail, are the grisly specifics. The tale becomes no less condemning at close range, but it does become far more complex. One can easily lose track of the disciplines in which Kolbert has been compelled to build a working knowledge: climatology, geology, stratigraphy, glaciology, herpetology (amphibians are dying out at a faster rate than any other class of animal), marine biology, veterinary pathology, entomology, dendrology, forest ecology, and so on. Kolbert is an economical and deft explainer of the technical, and, as a chapter set in an upstate New York cave filled with deliquescing bat corpses testifies, about as intrepid a reporter as they come.

Still, to describe for a general audience the existential condition of several million physiologically discrete organisms, as well as the knotty science of extinction itself, Kolbert has been forced to cull the herd, as it were. Her somewhat obvious yet effective organizing principle is to devote each chapter to a single species — either one already gone, as in the case of the great auk (Pinguinus impennis), a penguinlike bird the last of which was strangled on the tiny island of Eldey, Iceland, in 1844; or one in fatal decline, as in the case of the Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), of which there are now fewer than a hundred still living, most of them in zoos and reserves. (“Genetic analysis,” writes Kolbert, “has shown that the Sumatran is the closest living relative of the woolly rhino, which, during the last ice age, ranged from Scotland to South Korea.” The biologist E. O. Wilson has called the animal a “living fossil.”) This structure has a clear journalistic appeal in that it gives Kolbert the opportunity to do some colorful scene-setting in exotic places, tagging along with one or another pith-helmeted scientist to collect data in the Peruvian Andes, the Brazilian Amazon, the Scottish Uplands, the Great Barrier Reef, and (for anti-intrepid spice) a slimy creek in suburban New Jersey. The structure also has a didactic purpose. Though she never says as much, Kolbert has selected her subjects not because of their lost or endangered status but because each has something to tell us about how species become lost or endangered: each helps secure the case against human behavior. Kolbert nevertheless maintains a conspicuous ethical distance from her subject, no doubt both because she is one of the 7 billion defendants in the dock (and one who, I don’t think it’s churlish to note, has been racking up a disproportionate number of airline miles) and because of the likelihood that the sixth extinction is a foregone conclusion. The awkwardness of the latter fact is written into her hope, stated early on, that readers will gain “an appreciation of the truly extraordinary moment in which we live.” It’s a strikingly anodyne preamble to a book about annihilation.

Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, 250 years ago, humans have dug, developed, dammed, and diverted with such transformative fervor that the effects will be detectable in the geologic record 100 million years from now. We have become indelible.

This fact — of a planet newly definable in terms of the changes wrought on it by human civilization — has led many scientists to search for new terminology. According to the official timeline maintained by the International Commission on Stratigraphy, we still live in the Holocene, or “wholly recent,” epoch, which began at the end of the last ice age, nearly 12,000 years ago. (Geologists conceptualize Earth’s history as being divided into units of differing duration, among them the epoch, the period, and the era. The Holocene is the second epoch of the Quaternary, which is the third period of the Cenozoic era.) Over the years, a number of replacements for “Holocene” have been floated, among them “Myxocene” (from the Greek for “slime”) and “Homogenocene.” The late-nineteenth-century geologist Antonio Stoppani spoke of the “anthropozoic era,” a “new telluric force which in power and universality may be compared to the greater forces of earth.” Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the paleontologist and Jesuit priest, used the term “noosphere” (“world of thought”) to denote the increasingly transformative influence of human intelligence on the world. The prevailing neologism, however, coined in the early 2000s by the Nobel Prize–winning chemist Paul Crutzen (he won, appropriately enough, for helping to discover how humans were destroying the ozone layer), has been “Anthropocene.” The ICS is likely to vote on the validity of the Anthropocene, or “new human,” epoch in 2016. If they rule favorably, Kolbert writes, “every geology textbook in the world immediately will become obsolete.”

There’s a tragic sort of irony in this observation, for as The Sixth Extinction makes abundantly clear, the biosphere registers the inadequacy of our ideas long before we do. The early chapters of Kolbert’s book tell, for example, of the slow, tortured emergence of the science of extinction, which did not establish itself until the nineteenth century. Extinction, she writes, “strikes us as an obvious idea. It isn’t.” Aristotle’s ten-volume History of Animals is filled with animals but pretty much devoid of history. The Enlightenment view was that “every species was a link in a great, unbreakable ‘chain of being’ ” — this despite the fact that cabinets of curiosities throughout Europe were loaded with such broken links as fossilized trilobites, ammonites, and belemnites. Even after the voluble, Barnumesque father of paleontology, Georges Cuvier, had proved beyond a doubt the existence of espèces perdues (“lost species”) — arguing, moreover, that they’d become lost as a result of cataclysms, “revolutions on the surface of the earth” — the idea that we ourselves might be one such cataclysm was remarkably slow to dawn on the scientific mind. Darwin’s radical rejection of human exceptionalism, along with his insistence that species both emerge and die out gradually, blinkered him, Kolbert argues, to man’s exceptional destructive capacities. Darwin was certainly aware that extinctions could be caused by humans: during his visit to the Galápagos he learned of a species of tortoise being hunted into oblivion. Yet On the Origin of Species only briefly refers to “animals which have been exterminated, either locally or wholly, through man’s agency.”

In Darwin’s defense, in the 1850s man’s agency, while applied manically to those organisms deemed tasty or reducible to fuel or simply fun to shoot, was not quite the apocalyptic quantity it is now. Of the Anthropocene offenses driving the sixth mass extinction, overhunting has the most Victorian feel. The others — global warming, ocean acidification, the worldwide spread of pathogens and other invasive species, the wholesale destruction of ecosystems — gained their annihilative force from postwar booms in human population and commerce.

Kolbert takes pains to point out that there is something innately immoderate about Homo sapiens, a “Faustian restlessness” in the face of which other creatures (aside from perhaps rats) have never really stood a chance. One of her scientific guides, an excitable Swedish geneticist named Svante Pääbo, is even working to identify a “madness gene” differentiating us from other hominins:

Archaic humans like Homo erectus “spread like many other mammals in the Old World,” Pääbo told me. “They never came to Madagascar, never to Australia. Neither did Neanderthals. It’s only fully modern humans who start this thing of venturing out on the ocean where you don’t see land. Part of that is technology, of course; you have to have ships to do it. But there is also, I like to think or say, some madness there. You know? How many people must have sailed out and vanished on the Pacific before you found Easter Island? I mean, it’s ridiculous. And why do you do that? Is it for the glory? For immortality? For curiosity? And now we go to Mars. We never stop.”

But there’s a difference between a few thousand crazy people with ships and 7 billion crazy people with jet planes, chain saws, oil tankers, and explosives. The transportation alone is devastating. Global travel has increased to such an extent over the past century that it has in essence obliterated the evolutionary stability species gain from living in discrete habitats, among familiar predators, prey, flora, and parasites. The rules can change overnight. “During any given twenty-four-hour period,” writes Kolbert, “it is estimated that ten thousand different species are being moved around the world just in ballast water. Thus a single supertanker (or, for that matter, a jet passenger) can undo millions of years of geographic separation.” Those dead bats she reports herself clambering over were done in by a cold-loving fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, that had never before been seen in the northeastern United States, where the bats had flourished for millennia.

This global reshuffling is just one example of how rate of change rather than change itself — the latter, after all, is an evolutionary given — is the unprecedented heart of the sixth mass extinction. An even more potent example is ocean acidification, to which Kolbert devotes two full chapters. Ocean acidification has been called global warming’s “equally evil twin.” Just as the burning of fossil fuels alters the chemical composition of the atmosphere, it alters the chemical composition of the oceans. Approximately one of every three tons of carbon dioxide pumped into the air is absorbed by the oceans, where the compound dissolves and forms carbonic acid. Kolbert compares this process to a liver metabolizing alcohol. If you drink slowly, you’re not apt to get poisoned. Unfortunately, we are in effect dumping 2.5 billion tons of CO2 into our oceans each year. That’s like funneling hooch. The oceans are a third more acidic than they were in 1800; by the end of this century they will likely be 150 percent more acidic than they were at the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Given the dynamism of ecological processes it can be hard to predict results, but scientists have a pretty good idea what all this means for aquatic life. It means a paucity of vital nutrients, violent alterations in metabolic and cellular functions, blooms of toxic algae, and a radical reduction in the availability of carbonate ions in the water. This last effect, while dull-sounding, is important. Carbonate ions are what the large and varied class of marine organisms known as calcifiers use to develop shells, exoskeletons, and protective coatings. Calcifiers include barnacles, clams, oysters, sea snails, sea urchins, starfish, and many species of phytoplankton, seaweed, and reef-building coral. As Kolbert points out, the numerous reef systems throughout the world support a truly staggering array of life-forms — 9 million is the high estimate — and they are swiftly dying. Coral cover in the Great Barrier Reef (compared to which “the pyramids at Giza are kiddie blocks”) has declined by 50 percent in the past three decades. When it goes completely, so will many of the organisms that rely on it for sustenance and shelter. What’s left will be little more than ruins.

An Israeli oceanographer, Jack Silverman, summarizes the problem of the coral reefs for Kolbert as follows: “If you don’t have a building, where are the tenants going to go?” The question is rhetorical, but it raises an uncomfortable subject that The Sixth Extinction, for all its thoroughness, never truly addresses. That subject can be put in the form of another rhetorical question: From the point of view of the slumlord, or the developer, or the demolition crew — or whatever role humans would be assigned in Silverman’s metaphor — what does it matter where the tenants go? Our indifference to the tenants’ welfare, after all, is why they’re in trouble in the first place. We haven’t much concerned ourselves up to this point. Why should we start now?

Indeed, now may be the unlikeliest time for us to grow a conscience about how our rapacity is endangering other species, since we’re now aware of how frightfully our rapacity is endangering us. Kolbert’s previous book, Field Notes from a Catastrophe (2006), was about climate change, and was filled (as is this one, though to a lesser degree) with news of the terrible threats that phenomenon poses: the rising oceans, the spreading deserts, the intensifying storms. Humans, in particular the most vulnerable and poor humans, are in for a difficult time. More than a billion people live in low-lying coastal areas. Billions face the prospect (in many cases already the reality) of displacement, disease, scarcity, and resource wars. Nearly one in five humans, including 400 million children, currently live in extreme poverty. We have our own species to tend to, in other words, and we’re not even doing a good job of that.

Moreover, an abiding lesson one could draw from the study of mass extinctions is that the biosphere, ultimately, will be fine. Hasn’t it rebounded from previous cataclysms? Sure, it might take a long time, but time is exactly what the planet, in contrast with us, has plenty of. There are moments reading The Sixth Extinction when one is positively cheered by the geologic perspective on display. A giant rock smashed into Earth, baking it to a crisp — and still the planet recovered. More than recovered, it thrived! So profligate and inventive is the process of evolution, and so resourceful and fecund are the planet’s life-forms, that even now we can’t say how many species live here. Estimates have ranged from 3 to 100 million. And that doesn’t include bacteria or viruses.

Nor are humans a disaster for all species. It depends whose side you take. There are marine organisms that happen to do quite well in acidic waters. There are plants and animals that flourish in extremes of temperature. And what of that bat-killing fungus? Or the alien weed that chokes off the native tree? The opportunist is a species, too. Take it from a human.

None of this is to say that the collapse of biodiversity is not a tragedy. It is simply to say that tragedy is a human problem, inevitably defined in human terms. It is also to say that it is difficult to know just how to respond to the sixth mass extinction — or to The Sixth Extinction. Typically, condemnation is accompanied by a plea for reform. Yet the tale Kolbert tells, buttressed by science, is of an antagonist beyond reform, one who has always been beyond reform. In a late chapter about the extinction of the world’s largest terrestrial animals toward the close of the last ice age, she scrupulously weighs the evidence and concludes that pretty much every time a great beast stopped breathing it’s been because we showed up. This was 12,000 years ago; so what sense does it make, she asks, to date the beginning of the Anthropocene to the invention of the steam drill or to the baby boom? “Though it might be nice to imagine there once was a time when man lived in harmony with nature, it’s not clear that he ever really did.”

It’s even less clear, one might add, that he ever will — though like a violent child under discipline, he is coming to recognize the disharmony he causes, and to feel, if not remorse, then at least a sense of sadness about the carnage at his feet.