In the year 564 b.c., a pankratiast named Arrichion stepped into the ring at the Olympic games. Pankration was a nasty mélange of wrestling and boxing, very popular with the crowds, in which the only holds barred were gouging and biting. Arrichion had won the title in 572 and 568, but this time he found himself caught in a chokehold. His trainer urged him on from the sidelines, exhorting him to valor, reminding him, lest he had forgotten, what was expected. What a wonderful funeral speech if one can say: He did not give up at Olympia. Inspired, Arrichion shifted his weight and kicked, dislocating the ankle of his opponent. The man surrendered. But Arrichion’s move, which won him the match, had broken his own neck. His corpse went home with laurels.

The Greek motto was “Victory or Death,” but the story of Arrichion calls for a slight modification: Victory in Death. Two and a half millennia later, Victory in Death could be thought of as the guiding principle of American football, where championships come at the highest cost. The life expectancy of an NFL player is fifty-five years. Those who play professional football are nineteen times as likely to suffer from brain trauma–related illnesses as those who don’t. Repeated concussions — in seven years a pro will sustain, on average, 130,000 full-speed hits — cause dementia, clinical depression, memory loss, and suicidal ideation. In 2005 offensive lineman Terry Long killed himself by drinking antifreeze. In 2006, forty-four-year-old defensive back Andre Waters shot himself; doctors said his brain resembled that of an eighty-five-year-old man. Before safety Dave Duerson shot himself in the heart in 2011, he left a note asking that his brain be sent to Boston University. Ray Easterling, another safety and the lead plaintiff in a concussions lawsuit against the league, and Junior Seau, a linebacker, both shot themselves in 2012. More than a hundred current and former players have signed documents donating their brains for postmortem analysis.

Things are much the same in college football, which feeds a few players to the pros and forgets the rest. In 2011, fullback Derek Shelly fell unconscious during a drill for the Division III Frostburg State Bobcats. (The drill consisted of the players bashing into each other, helmet-first.) He never recovered. Still the bands keep marching, and the lights keep flooding the fields. “I do think that in the state of Alabama, anybody planning a wedding is gonna get out a schedule, because the worst damn thing you can do is have your wedding on the Alabama–Auburn game or the Tennessee game, because nobody will come to your wedding. . . . As a matter of fact, in the state of Alabama, I wouldn’t even plan a funeral when Alabama is playing Auburn. You can die, but you’re gonna wait ’til Monday.” That’s Winston Groom, author of Forrest Gump, talking to journalist Wright Thompson in an essay titled “Pulled Pork & Pigskin” from the anthology football: great writing about the national sport (Library of America, $30), edited by John Schulian. The book is a tribute to the sublime beauty and ugliness of our national obsession, with selections from newspaper columns, magazine profiles, oral histories, and memoirs on the NFL, college ball, and high school teams. We even meet a league of sixth graders out in Allen, Texas, blessed with a running back whose trainer brags he’s “the best eleven-year-old football player in America. In America.”

Football viewership is probably the most diverse demographic in the country, by race, gender, religion, geography, political party, or any other measure, but if this collection is any guide, football writing is a white man’s game — a lyrical, macho, sentimental, swaggering white man’s game. There’s Grantland Rice, Red Smith, Frederick Exley, George Plimpton, Arthur Kretchmer, Richard Price, Michael Lewis, Buzz Bissinger, Bryan Curtis, Paul Solotaroff, and two dozen more. And two women. Don’t leave out the women! Jennifer Allen, born the same year the Bears drafted Mike Ditka, reflects on her dad, coach Mike Allen, who always misspelled her name. (“Mom said that with over forty men on his Rams roster and over three hundred plays in his playbook, I was lucky my father even remembered my name.”) Jeanne Marie Laskas’s profile of the Cincinnati Ben-Gals cheerleaders, all hair and heart and heaving cleavage, is a tour de force. The squad includes a biologist who had trouble making the “sexy look” for the calendar and a construction worker puking with nerves over being Cheerleader of the Week. Before trying out for the squad, she had poured the concrete in the stadium.

In the early years — before the video-game series Madden had generated $4 billion in revenue, before Hank Williams Jr.’s song for Monday Night Football was pulled after the singer compared President Obama to Adolf Hitler, before Cleatus the Fox Sports Robot became the protagonist of fan fiction — football writing was an art of recap disguised as a prose-poem contest. (“It was a hairy crowd,” writes Smith of the 1947 Harvard–Yale game, “wrapped thickly in the skins of dead animals and festooned with derby hats, pennants and feathers of crimson and blue.”) As time passes, the angles get thinkier. In 1967, Jerry Izenberg visits Louisiana’s Grambling College, where nearly twenty years earlier a fullback named Eddie Robinson became the first player from an all-black college to be signed to a pro team. Thirty years later and two hundred miles closer to New Orleans, Ira Berkow reports on the tribulations of Marcus Jacoby, the first white quarterback at historically black Southern University, who quits after two seasons.

The pressure is extraordinary. Players use human-growth hormone off the field (to bulk up) and amphetamines on the field (to freak out). When it’s all over, many retire into poverty or squalor. In 1972 Paul Hemphill meets Bob Suffridge, washed-up All-Time All-American, a fifty-five-year-old alcoholic living by special arrangement in a nursing home. Others are neglected by the indifferent Players Association, whose definition of disability is practically dead.

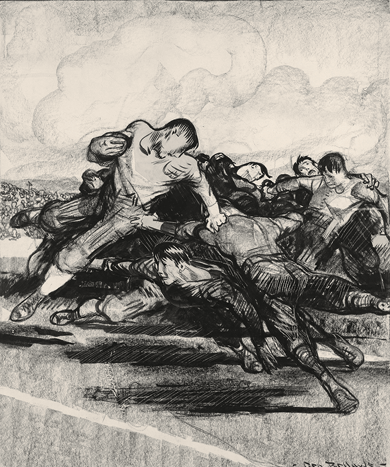

Football, a crayon-and-ink drawing by George Bellows. Collection of Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, Amherst, Massachusetts. Gift of Albert Sylvester (Class of 1956), Susan Hopwood, Amy Katoh, and Duncan Sylvester in memory of their parents, Albert L. (Class of 1924) and Elizabeth E. Sylvester © Bridgeman Images

The most poignant essay in Football is “The Best Years of His Life” by John Ed Bradley, who never got over playing center for LSU. “Do others wake up from afternoon naps and bolt for the door, certain that they’re late for practice even though their last practice was half a lifetime ago?” he writes. “If it really ends, I wonder, then why doesn’t it just end?” But some writers’ glasses are too fogged with valor. “I never saw war, so that is still my vision of manhood,” Frank Deford rhapsodizes on meeting his childhood hero, quarterback Johnny Unitas. “Unitas standing courageously in the pocket, his left arm flung out in a diagonal to the upper deck, his right cocked for the business of passing, down amidst the mortals. Lock and load.” He wrote this in 2002, the year after Panthers wide receiver Rae Carruth was sentenced to twenty-four years for hiring a man to shoot Cherica Adams, his pregnant girlfriend. She gave birth to a son, Chancellor, before she died.

There is neurological evidence that football causes violent behavior: Lowered inhibitions and quick-trigger tempers are symptoms of brain trauma. It’s a cycle. You knock a guy out, maybe he comes back a little quicker for the kill next time. But what’s it like to get hit by two hundred pounds in pads? Safety Joey Browner, who spent Saturdays practicing the Japanese sword art iaido and Mondays struggling to get out of bed, suggests this simulation: “Grab a football, throw it in the air, and have your best friend belt you with a baseball bat.”

Football originated in the 1820s as a hazing ritual at the better East Coast colleges, where it caused so many broken bones that Yale and Harvard banned the game in 1860. Students kept playing anyway, working out rules and a scoring system. Their version makes today’s game look arcadian. There were no pads or helmets, and the only way to move the ball was for phalanxes of players, arm-in-arm, to knock their skulls straight against each other. Eighteen boys died playing in 1904, most of them at prep schools. After Theodore Roosevelt’s son broke his nose on the field at Harvard, the President met with college officials. Among the reforms issued was the legalization of the forward pass.

This thumbnail history begins Steve Almond’s against football: one fan’s reluctant manifesto (Melville House, $22.95), a small and powerful and slightly too-ambitious book that wants to rouse the political will Roosevelt summoned a century ago. Almond’s offense is multi-pronged. There’s the NFL’s financial chicanery, with stadiums funded by taxpayers and profits pocketed by wealthy owners; the ruined lives of college “amateurs” who forfeit both career and education, if they’re lucky enough not to be thrown out mid-scholarship; the brain damage of the retired pros. And then there’s the rest of us, glued to every replay, following the close-ups, listening for every crack of helmets butting. Almond insists that watching football does more than feed an appetite for violence. It’s a kind of modern-day human sacrifice, and it makes us more likely to go to war. “Watching football . . . actually causes us to be more bellicose and tolerant of cruelty, less empathic, less willing and able to engage with the struggles of an examined life,” he writes.

Almond visits the lab of Dr. Ann McKee, co-director of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at Boston University, who gets the players’ brains when they die. A longtime Packers fan, she tells him that it’s impossible to change the league. He doesn’t agree. “Football is a form of entertainment,” he writes, “not a chip that gets implanted in our necks at birth by the Overlords.” He’s a fan, too, formerly rabid and now guilt-ridden, of the most embarrassing of teams: the Oakland Raiders. Almond is a sympathetic narrator, his evidence incontrovertible, the moral authority firmly on his side. But will he convince anyone? After he published a magazine piece on the subject earlier this year, he was flooded with hate mail. “I read an article you wrote about football and I couldn’t help but think of a slutty girl I knew growing up,” one admirer wrote. “I thought she had the biggest vagina I’d ever seen before until now.” Almond adds it to his collection. “Nearly every piece of hate mail I received made reference to my vagina,” he writes, “which was usually characterized as very large.”

“Oh gods! It is Pentheus’s head I hold.” So laments Agave, mother of King Pentheus, in Scottish poet Robin Robertson’s new and vivid translation of Euripides’ bacchae (Ecco, $19.99). In the throes of a bloodthirsty orgy she has just torn her son limb from limb, thinking him a mountain lion to hang as a trophy on the royal walls. Pentheus’ crime, for which Dionysus has orchestrated this most horrific of punishments, was to refuse to honor the god, who held all Thebes in his thrall. That is, all the women. They call themselves priestesses, Pentheus rages, but they are merely drunk, and, thus fortified, “slip into the shadows to satisfy the lusts of men.” He is disgusted by their debauchery. “It’s always the same: as soon as you allow drink / and women at a festival, everything gets sordid.”

These words become a prophecy. For although Pentheus wants to eliminate the intemperate rites being celebrated in the hills, he also wants to watch. Dionysus, disguised as a wandering stranger, persuades Pentheus to disguise himself as a woman, better to spy on the maidens. The gruesome climax of his undoing takes place offstage, narrated by a messenger who delivers color commentary in lurid red. Mother Agave pulls his arm out of its joint on one side while on the other her sister rips off skin by the fistful. “One woman cradled an arm; / another had a foot still warm in its shoe. / His ribs were clawed down to the white, / and every woman’s hands were daubed with blood / as they tossed chunks of him / back and forth like a game of ball.”

Sophists partial to football’s current regime excuse themselves by arguing that players knowingly choose to incur risks. But in the Bacchae, even the gods’ playthings are held to account for the game’s horror. Agave’s tragedy is realizing that it was she who killed Pentheus and paraded his head on a pike — she who was blinded with passion, and yet she who bears responsibility for the outcome. In the flush of excitement Agave mistook her son for a prize and herself for a victor, but, as the messenger reports, “the only prize that she takes home is grief.”