On Google Maps the farm looks like a space station or a huge fallout shelter, but as I drive down the shop-dotted Main Street of Martin, Michigan, and through its bucolic neighborhoods, I see only lovely fall leaves, long yards, and friendly houses. I cross a thicket of trees, and abruptly the town gives way to a vast plowed field. Far off lies the farm, silver silos that jut into the sky over a collection of giant warehouses, home to 2 million hens. I drive toward them. The tremendous barns rise around my car, and the air fills with the sound of machinery and the sharp smell of ammonia. I pull into the tiny parking lot of Vande Bunte Eggs family farm. I’ve come to see the cages.

Despite the noise, the farm appears empty and there is no one in sight. I walk to the office building behind the original Vande Bunte home, a small rectangle on the map compared with the outsize barns. The farm opened just after World War II, in the wake of the era of the modern henhouse, and is run today by two sons of the farm’s founder, Howard Vande Bunte. Inside, a grandson, Rob Knecht, greets me. He’s thirty-one and amiable, but he says, “Good to see you!” with a weary smile and some nervousness. For weeks he and I have been engaged in a series of negotiations over the phone and on email. “You have to understand the risk I’m taking here,” he’d said.

I did understand. In the 1970s, “Chickens’ Lib” was a handful of women in flower-print dresses holding signs, but in the past decade farm hens have become almost a national preoccupation. The agriculture industry has been subject to an onslaught of bad press fueled by the release of undercover videos taken by investigators who apply for jobs as farmhands — or, more rarely, farmhands who become whistle-blowers — and shoot video inside the megafarms’ barns. Animal-protection groups post footage online of birds in extreme confinement and being roughly handled. Criminal charges are filed, chain retailers drop the egg farmer in question, and citizens or legislators vote for better conditions for the hens. This cycle repeats itself.

The agriculture industry has responded in a variety of ways, most controversially by lobbying states to pass what are known as ag-gag laws, making it a crime for anyone to film, photograph, or record inside a barn unless the farm has hired the person specifically to do so. These laws are in place in seven states as of this writing. But the public by and large seems to distrust such laws. In 2013 and 2014, twenty new ag-gag bills and amendments were introduced in fourteen states and all but one were defeated.

Still, it is rare for anyone, especially a reporter, to be allowed onto an industry farm. But Knecht is in an awkward position. I first met him six weeks earlier in Lansing, Michigan, where a few dozen farmers, food-service workers, and university associates had gathered for a conference called “A Peek into the Future of Egg Farming” held by the industry trade group, the United Egg Producers. At the conference Knecht told me the industry needed to become more transparent and that his company was transitioning to the new “enriched cage systems.” He and his uncles are proud to be pioneers in what the industry calls the latest and largest-scale developments in hen welfare. They are hoping enriched cages will be the compromise solution, the place where welfare and productivity meet, and that these cages will become the national standard, as they already are in England.

If they’re proud of what they’re doing, I called him and asked, Why couldn’t he let me see?

“With every fiber of my being, I want to let you come,” he said, “but I’d be really leaving myself open.”

Next we had a volley of phone calls and emails that ended in his invitation. I agreed to follow the rules applied to any visitor: I would come to the farm alone, I would not film or take pictures, I would leave my phone in the car, and I would view only the new “enriched” barn, not the conventional “battery cage” barns.

Finally, Knecht shakes my hand and shows me in.

Since 2008, when California voters passed Proposition 2 — which requires that hens be able to “lie down, stand up, fully extend their limbs and turn around freely” — the question of where and how to keep the approximately 295 million layer hens that are alive in the United States at any given time has led to big, expensive political and legal battles around the country. Both egg farmers and animal advocates will tell you stories of the creative legal maneuvers, the spook-level secrecy, the unlikely alliances, and the eleventh-hour vote reversals — tales of heroism and defeat that I never would have associated with the cardboard cartons at the grocery.*

The industry isn’t hiding that its hens are kept in cages, but they aren’t advertising it either. On egg cartons and in ads you see old-fashioned barns and fluffy chickens, not cages. The farms themselves are often far off highways, behind rows of trees or barbed wire, some of the farms monitored by security trucks or cameras. If you search online you can find smiling farmers standing between aisles of battery cages while a hundred thousand hens cluck around them. The farmers’ relaxed postures urge you to feel calm and undisturbed about all those hens, that this is normal, natural. And maybe the hens do look all right to us. Indeed it’s hard to say what an “unhappy” hen would look like.

We have conflicting notions about farm animals. This is due in part to the gulf that has widened between the farmer and the public as we have less and less access to the animals. Before World War I, the majority of eggs came from people keeping a few chickens in their backyards in the suburbs. Today, barns of 150,000 hens are run by 1.5 men on average (one full-time worker in a single barn, another split between two barns), who are more mechanics than farmers. In 1976 there were 10,000 egg producers in the United States; in 2014 only 177 egg producers represented 99 percent of all layer hens in the country. But large-scale production has dramatically risen: in 1994, 63 billion eggs were produced in the United States; by 2013 that number was 82 billion. Meanwhile, one third of the eggs we consume have become invisible, finding their way into our processed foods — mayonnaise and baked goods and sauces — so that we don’t notice we’re eating them. Yet our collective public image of an egg farm continues to include hens sitting on their eggs in nests, hens trotting around a barnyard, hens standing against a backdrop of grass and trees.

Many egg farmers, such as Knecht, believe they are treating the hens well, but they still sense they have something to hide: big agriculture, especially the egg industry, is running against the tide of changing public values. As the many current conversations about animal use and sentience attest, we are re-evaluating our relationship to animals. Our views are shifting and our circle of empathy is widening, yet the scale on which we are consuming eggs is immense and still growing, and there is no other way to satisfy the demand. This seemingly minor debate about cages is symptomatic of a much deeper — and growing — incompatibility between our beliefs and our consumer desires. The questions, then, may be reflective of the times: What is it like for a hen to live in a cage? And, perhaps more important:

Does it matter?

Birds — egg-laying yet warm-blooded, not quite mammals, not quite reptiles — have tight, smooth brains that handle information differently than ours do. Mammals think mostly with their cortical cells, which sit on the surface of the brain in large, bulky folds. It may seem logical to conclude that because birds don’t have these bulky folds they don’t think, but for birds, whose brains have been evolving as long as or longer than ours, that heavy mass of cortical cells is not convenient for flight. Instead they have developed compact cortical areas that work in similar ways to our own.

The oldest relative of the chicken might be the Tyrannosaurus rex. The Gallus gallus domesticus, our domestic chicken, descended from the jungle fowl of Southeast Asia and traveled, by way of humans, through Africa to Europe and finally to the United States.

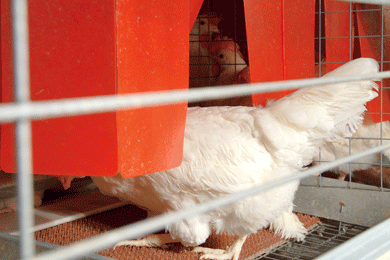

Photographs of the Vande Bunte Eggs enriched housing system © Adam Dickerson/Big Dutchman USA, courtesy Vande Bunte Farms

In nature chickens live in smallish groups in overlapping territories. They have complicated cliques and can recognize more than a hundred other chicken faces, even after months of separation. They recognize human faces too. They have distinct voices and talk among themselves, even before they hatch. A hen talks to her eggs and the embryos answer, peeping and twittering through the shells. Adult chickens have at least thirty different categories of conversation, centered around, to name a few, mating, eating, nesting, rearing, and warning, each with its own web of coos and calls and clucks.

According to the animal-studies professor Annie Potts, hens all have different dispositions. They have best friends and rivals. They are surprisingly curious. They play and bathe in the dust. A flock of chickens in nature resembles a lively village, with the males crowing and dancing around the females in courtship, the young ones sparring, most of them climbing into the trees at night to sleep.

Their eyes are especially ingenious. Human eyes work together and focus on one location, but chickens’ eyes work separately and have multiple objects of focus. A hen can look at a morsel on the ground with one eye and scan the area for predators with the other. When you see a hen cocking her head at you at different angles, she is getting a series of snapshots from different perspectives, studying you. If you study her back, she’ll step closer and sit next to you. When I sit in a barn with a flock of hens, they come right over to me, hop up on my stool, poke at my pen, look into my face.

Knecht gives me a neck-to-toe biosecurity suit to put on that looks and feels like paper pajamas. We are standing in the entryway to Vande Bunte’s enriched-colony barn. Joining us is Dr. Darrin Karcher, whom I also met at the previous month’s conference. Karcher’s parents run a tiny backyard breeding operation, and although Darrin followed them into the chicken business, he turned off in another direction, becoming a poultry scientist at Michigan State University and for the large commercial-egg industry. Though perpetually smiling, he has a wary, professional energy.

We enter the barn and step into a powerful din of fans and machinery. The barn is enormous, more than 450 feet long, nearly 25 feet high, and completely enclosed, with no natural light. The air is dense with dander and dust and the smell of chickens and their ammoniac manure. Seven rows of cages multiply down the length of the barn and rise eight tiers high in two stories. Each cage is twelve feet long, four feet wide, and contains more than seventy-five hens. Attached to the barn by walkways are three more barns identical to this one. Over my head, on a wide conveyor belt, eggs slowly travel by. Knecht gamely waves his arm, and we proceed into one of the narrow aisles. The aisle is very, very long. The cages rise from my feet to far overhead on both sides, creating seven loud walls of hens, honeycombed in, two Le Corbusian stories high. Hundreds of heads poke out from all heights.

The chicken industry was the first of the ag industries to control every stage of production. In 1879, Lyman Byce of Petaluma, California, invented the incubator, allowing eggs to be hatched away from the mother hen, but the real breakthrough for egg farmers (or, as one pair of historians put it, the “bit of research fatal to the hen”) came during the Depression, when scientists discovered that the hen’s laying cycle is linked to light. Light triggers hormone production in the hen’s pituitary gland, which signals her ovaries to make an egg. Before this discovery, families were dependent on the seasons for their eggs. Hens laid their eggs in the spring, molted in the fall, rested in winter. (When a hen molts, she sheds her feathers and grows new ones in preparation for winter.) Depending on the breed, hens laid as few as thirty eggs a year. By increasing the light, farmers could create a perpetual artificial spring. And by taking away the light — and food, so that hens lost 30 percent of their body weight — farmers could bypass the natural annual timetable and trigger hens into speedy molts and a swift (and lucrative) second laying cycle. Hens moved indoors and into cages. The modern henhouse was born. Egg production continued to rise as scientists tinkered with the details: Hens are fed vitamin D to make up for the lack of sunlight. They are given wire to stand on, instead of perches and straw, to keep the eggs away from the excrement. Wire floors are slanted so that the eggs roll to the front of the cage and out, though this requires the hens to stand on a slant, which is hard on their legs and feet. The tips of hens’ beaks are cut off to keep them from pecking one another in close quarters. Male chicks are sorted out and rendered (layer hens’ meat is not used for human consumption). Today, on average, industry hens produce 275 eggs a year, one every thirty-two hours. After a year and a half to two years the hens are “spent,” meaning their egg production has waned, and they are removed and destroyed.

Knecht and Karcher are taking turns explaining to me the features of the enriched housing system, which is a study in automation. Chains move in the feed, belts carry out the eggs, belts loop under each row to catch the excrement of 147,000 birds. The entire barn is bathed in dim, purplish lighting. There’s a layer of dust over the cages, in places thin, in places thick.

This dust has been a cause for concern. Flakes of feed, dander, feathers, and excrement waft through the barn and settle over the cages. The dust gathers and accumulates, turning into a dense coating of grime that attracts flies and makes it hard to breathe. Cleaning chemicals could kill the hens, so the barns are deep-cleaned only every year and a half to two years, when a bird colony is sent to slaughter.

There are no federal regulations regarding air quality inside the barns, but for an egg farmer to receive UEP certification, the air in the barns must have an ammonia-concentration level of less than 25 parts per million. One way farmers meet this requirement is to set up enormous vents at the front of the barn and giant fans at the back to draw the ammonia-laden air out and fresh air in, but this process creates different problems. The fans blow bits of feather and excrement out into nearby communities, forests, water, and preserves, destroying habitats. In one recent case, the ventilation fans of a 3 million–hen farm sent nearly 5 million pounds of pollutants in the direction of a wildlife refuge a mile downwind. The enriched barn I’m in has young birds, and the dust is still minimal, but it’s already present.

The sound of 147,000 chickens is sort of an overwhelming roiling moaning or droning, and it reaches the ears in what I can only describe as layers. The shallowest sound comes from the individual hens who cluck and ululate nearby. The deepest layer is a low cooing that rises from all corners of the maze over the rumble of the machinery. Above me I glimpse through the metal a second story of hens that is arrived at by a set of stairs and a catwalk. I crouch and see the lowest tier of birds at my feet. I myself am encased within this tremendous wire-and-steel contraption. We walk and walk, and I still cannot see the other end through the light haze of dust and dander. The hens scuttle away from us as we pass, trampling one another with alarming violence to get to the backs of their cages. “We’re wearing white,” Knecht explains. “They’re used to the blue uniforms of the workers. The young hens startle easily.”

When I think about how this is only one barn on one farm, and that there are sixteen barns on this farm alone, and that this farm is only moderately sized compared with the others folded into the flatlands of America, I begin to feel the enormity of this business: the number of eggs being laid, the sheer noise of the hens and the fans and the machinery, the amount of manure involved, the mass of creatures. From whatever angle I approach it that’s what I take away: the tiny beside the huge, the unimaginable scale.

Finally we reach the other end. “This,” Knecht says proudly, “is the future.”

What I’ve just seen is the new enriched system, the “Cadillac of houses,” he calls it, what he hopes will be the compromise solution. At this point only one of the farm’s sixteen barns is a fully enriched house, and three more are “enrichable,” meaning they can be converted, but Knecht says they intend to change over all their housing in the next decade. The hens here have a little more space per bird than in traditional battery cages — in this case ninety-three square inches, or about the size of a sheet of paper, versus the standard battery cage at sixty-seven inches per bird. The hens also can get off the wire in the cages and stand on steel perches, and they have scratching pads and alarm-red privacy tarps they can gather behind to lay their eggs. The enriched-cage barns are cleaner, too: the flies are fewer, since the manure is carried away on belts instead of piling up in a pit below the cages.

But only about 1 percent of layer hens in the United States live in these conditions, which are luxurious by industry standards, wasteful even, according to some egg farmers.

I smile at Knecht. “Can I see a traditional barn?”

Knecht looks askance at Karcher.

Egg producers remember with a shudder the great recall of 2010, when more than half a billion eggs were recalled in the wake of widespread salmonella poisoning, nearly 2,000 cases in a matter of months. The farmer at the helm of this fiasco was the infamous Austin “Jack” DeCoster, and this wasn’t his first time in the papers. Over the years DeCoster had been fined by both federal and state regulators over accusations of mistreatment of workers, habitual violation of environmental laws, animal cruelty, and sexual harassment and rape by company supervisors. The FDA reports of the DeCoster barns are as hilarious as they are horrendous: piles of excrement up to eight feet high, barn doors that “had been pushed out by the weight of the manure,” “live flies . . . on and around egg belts, feed, shell eggs, and walkways,” “live and dead maggots too numerous to count.” Salmonella dotted the farm, turning up everywhere from a food chute to the bone meal.

Today, concerns about egg safety have mostly been supplanted by the topic of animal welfare. Since 2008, layer-hen investigations have been going on all over the country, and farmers are scurrying to show how much they care about their birds. Yet when scientists hired by the egg industry talk about what hens need, most of what they say contradicts what scientists involved in hen advocacy say hens need. Industry scientists say that hens like small spaces and are reluctant to venture outside; hen-advocate scientists say that hens like to go outside to walk and run and fly their awkward short flights. Industry scientists say hens are safer in cages, protected from diseases, bad weather, and predators. Advocate scientists say hens need more space for their physical and psychological health than even the enriched cages provide. Industry scientists prove their case by citing lower mortality rates for caged birds. Advocates prove their case by citing caged birds’ excessive feather loss, osteoporosis, and cannibalism. The industry scientists say cannibalism is mostly avoided by trimming birds’ beaks and that beak trimming rarely results in long-term suffering. The advocates describe “debeaking” as very painful and say that farmers need to use it only because they keep hens so confined. They say that the tips of hens’ beaks are extremely sensitive, that hens use their beaks the way we use our fingers: to explore, to defend, and to experience pleasure. Thus the two sides continue to at once describe and disagree about what it is like for a hen to be in a cage.

After Proposition 2 passed in California, the egg farmers watched while the Humane Society had similar successes in Michigan and Ohio. They knew that more legislation would be on the way: the Humane Society has never lost a farm-animal-protection ballot initiative. The UEP put forward their solution, a federal egg bill — in fact, an amendment to the 2014 Farm Bill — requiring enriched cages nationwide, hoping this measure would satisfy advocates and egg farmers alike. But then more groups objected, unexpected ones — the beef and pork industries, who feared the precedent might result in other federal regulations, in particular a ban on veal and gestation crates — and the bill failed.

There are in fact no federal regulations regarding the treatment of animals on farms. We’ve heard of the Animal Welfare Act, but it turns out to exempt all animals on farms. There are only two federal protections that do apply to farm animals — one for slaughter and one for transportation. The USDA exempts chickens from both.

Why chickens aren’t included in the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act is somewhat of a mystery. The act requires that “livestock” be slaughtered in a way that “prevents needless suffering.” In the USDA’s interpretation, the word “livestock” does not include poultry. In early drafts of the act, the word “poultry” did appear, but by the time the act reached its final form, it was gone. One lawyer I spoke to said, “Presumably they aren’t included because there are so goddamn many of them!” In 2013, 282 million layer hens were destroyed, most of them gassed and ground up for pet or farm-animal food. Layer hens have a natural life span of up to ten years, but they are spent by two.

Theoretically, hens could be eligible for protection under the various state anticruelty statutes, but convictions under these laws are extremely difficult. Besides, in forty states, the anticruelty statutes have been amended to say that any “accepted,” “common,” or “customary” farm practice is exempt (or have similar wording). This essentially means that no farm activity can be deemed cruel, no matter how painful or unnecessary it is (beating, hanging, and starving have all been dismissed as normal farm practice), as long as enough farmers are doing it. In effect, this allows the industry itself to define what is or is not cruel. Certification programs such as the UEP’s are designed to fill this gap. They provide guidelines for egg farmers to follow. But many of the undercover investigations that have revealed objectionable conditions and behaviors have involved UEP-certified farms.

One farm, for instance, Quality Egg of New England, passed a UEP inspection only a few months before a 2009 government raid of the facility that resulted in convictions on ten counts of animal cruelty, $130,000 in fines, and prompted Temple Grandin to call the farm “a filthy disgusting mess.” The air quality was so bad, according to a witness, that, following the raid, three of the government agents had to receive medical attention. It’s possible that the guidelines aren’t strong enough or just aren’t followed. The setup may be endemically flawed: the egg farmers fund the UEP, fill the UEP’s board, and pay for audits.

I ask Knecht about the undercover videos. He says the clips are of “outliers” and “extreme examples,” and that they do not represent standard practices on farms. Other farmers I spoke to said the clips are staged or highly edited. One farmer said that undercover investigators have been known to bribe workers to mistreat the animals.

I contacted the two activist groups that had done the most egg-farm investigations, Mercy For Animals and the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), and asked if I could view their unedited footage of the insides of layer hen barns. MFA asked me to sign a nondisclosure agreement to protect the identity of the investigators, then mailed me an enormous padded envelope full of DVDs, which I sat and watched for days. HSUS invited me to come to their office and view as many hours as I liked. I flew to D.C. and walked every morning from my hotel to the HSUS Gaithersburg, Maryland, office, where I watched hours of unedited footage in a basement cubicle. The investigators made themselves available for questions. I watched forty-nine hours of footage of nineteen layer farms in the United States and two in Canada, from nine different investigations conducted by five investigators between 2008 and 2013.

When an investigation is released, farmhands are often blamed as the guilty parties. Indeed, most of the handling I saw was violent, but it was systematic, repetitive, and mechanical, intended to get the job done quickly, not to abuse. One investigator had been hired as a bird handler, responsible for any task that involved touching the birds: filling up barns with young hens, emptying barns of spent hens, vaccinating hens, debeaking baby hens. He and his crew traveled from state to state, farm to farm, during the summer of 2011. They spent twelve-hour days doing work that was at once monotonous and backbreaking. Often they had to move thousands of birds in a matter of hours, so there was no way to do it gently or by recommended guidelines. Hens were pulled from their cages upside down by the legs or tossed into cages by the neck. Hens were carried up to six per hand at a time. During beak trimming, workers would place each chick’s beak into a hot-iron guillotine-like machine, and when they snapped the tip of the beak off, the chick’s face smoked and the chick struggled. The workers had to move so fast that they couldn’t always be precise and sometimes had to do the routine more than once.

The UEP requires for certification that all workers watch a video instructing them that birds should be lifted “one or two at a time by grasping both legs and supporting the breast when lifting over the feed trough,” and all workers must sign a “code of conduct” form, which serves as protection for the farms. In all nine investigations I watched, I saw almost no birds handled in this manner. “If I’d handled the hens that way,” one investigator told me, “I would have been fired.”

I did see intentional abuse, however, especially when the workers were frustrated or tired. I saw workers drop hens on their heads, kick hens, throw them, swing them back and forth by the legs, blow cigarette smoke into the cages. I also saw workers cuddle hens on occasion, lament the hens’ sad lot, get down on their hands and knees to try to help a hen untangle herself from the wire.

In the summer of 2011, it was the investigator’s bad luck that a heat wave set in. There is no air-conditioning in the barns, and the agriculture industry by law is exempt from paying workers overtime. The investigator and his crew complained bitterly. I watched the workers dizzy with heat, in a labyrinth of cages in a cavernous barn, hens screaming all around, the air thick with flies and dander, dead hens scattered on the floor. The investigator got heat exhaustion and wound up in the emergency room, but the next day he was back, shoving birds into cages and complaining deliriously, half to the camera, half to himself.

At the end of the day, the handling crew must “walk the pit.” Battery cages are built on an A-frame, the tiers stacked six or seven high. The entire apparatus is placed on the second floor of the barn with an opening underneath, so that the excrement will drop through the wire and the opening to the first floor, which is a huge open room called the pit. The pit slowly fills over the lifetime of the flock. The piles of excrement can grow to be six feet high, and the ceilings are low. Stray hens find their way into the pit, either by falling through holes in the wire caging, or being mistaken for dead and being tossed or kicked in. The crew had to go down and catch the hens running around the mountains of manure. I watched ghostly scenes of the crew stringing out along the shadowy pit, calling to one another, of workers clomping up the stairs, swinging the captured hens by the legs. I watched workers shovel walkways through the excrement like it was snow.

Hens dying in the cages is a problem. The cages in all the videos were extremely small, the size of a file drawer. The birds tried to stick out their heads and stretch their wings in any way they could. Wings got stuck. The hens’ bone density is low, because so much calcium is needed for the high number of eggs they lay. If they break a leg, they can’t stand up to drink from the suspended nipple, and they become dehydrated. Hens also suffer from prolapsed uteruses, which is when the overstrained uterus, in pushing an egg out of the hen’s vent, fails to retract, leading to infection and death.

In nature, hens on the lower end of the pecking order can avoid being pecked by simply moving away from the pecker. Inside the cage, there is no place to go, so a hen can be viciously attacked by her cagemates until she is dead or seriously injured. And once a hen is dead, her cagemates stand on her because there is so little room. She winds up decomposing and being pressed into the wire and sticking to it. The workers have to rip hens off the bottom of the cage, a practice I heard referred to as “carpet pulling.”

I saw many more dead and half-dead birds pulled from cages than I could count. Sometimes it was hard to tell if a hen was dead or alive. I saw bloody birds, bloody eggs, birds with almost no feathers, birds that looked as flattened as Frisbees, garbage bins full of dead hens. In footage from one facility I saw whole dumpsters full, thousands of dead hens tossed in heaps and carried off in bulldozers.

One investigator was on his second day on the job, according to the date on the video. He was walking up and down the aisles fixing egg belts. He stopped to peer into a garbage can half full of dead hens — a common sight at all the facilities. He was taking footage of it, when suddenly one of the hens moved a little.

Now, this man is a vegan and the most serious kind of activist you can find. He has devoted his life to helping these creatures. He pulled the live hen away from the dead ones and took her out. He looked her over — battered, but breathing. He walked over to the cages, carrying her, but paused and turned back and forth. Clearly he didn’t know what to do with her. She’d be trampled in a cage. He walked back to the garbage, whispering, “Goddamn it,” and put her in. Sighed. Then he went and found his supervisor and said in Spanish, “There’s a chicken in the garbage but the chicken isn’t dead.” The supervisor listened, then kept talking about the egg belts in Spanish.

The investigator returned to the garbage.

Now the hen was standing in the garbage bin on top of the other dead hen bodies, looking around. She flapped, tried to fly out, hit the side of the bin, and fell back in. You could hear her make a cooing noise. The investigator grabbed her out of the garbage and started walking.

The video cut.

I hurried to call the investigator. “What happened to that hen?” I asked. “The live one in the garbage?”

“Which live one in the garbage?” he said.

Rob Knecht is clearly not someone who is maliciously finagling the law and intentionally torturing chickens. Standing with me now in the enriched barn, he seems to sincerely believe that this tremendous tangle of wire he is showing me, this dim, windowless, dander-filled warehouse, this tower of thin cages, is a perfectly suitable home for these lively, curious creatures — the animals possessed of wings, the universal symbol of freedom. Knecht’s cheerful demeanor, the confidence with which he points out the amenities of the enrichments, speaks to his conviction that the system can be rebuilt around humane treatment and that this, what he is showing me, is the acceptable compromise.

But the enriched cages obviously do not address the essential problems of radical confinement: the hens are still packed into stacks of small cages and never see the light of day — never run, jump, or fly. They suffer through beak-trimming, rough handling, wire cages, the destruction of their social systems, and then an early death. The enriched cages are slightly bigger and have a few somewhat impoverished amenities, but they do not resolve the moral dilemma that farm animals present to the contemporary mind.

Let’s consider what a truly humane farm would look like. We might postulate that it would allow hens to approximate the sort of lives they would have in nature, where they live in small groups on a range large enough for them to maintain their social order without having to be debeaked (though the absence of cocks and chicks is already unnatural). Animal Welfare Approved, the certification program most generous to the birds, requires no fewer than four square feet per hen on the open range, “in stable groups of a suitable size to uphold a well-functioning hierarchy.” A flock of a hundred hens seems a fair number, since beyond that, the hens have trouble remembering faces and their place in the hierarchy, which is when disorientation and aggressive pecking set in. The range would have dirt and straw for dust bathing, grass to peck in, and enough space to run and jump and fly short distances. The hens would have a barn in which to build nests and lay eggs, trees to climb into and roost, sunshine for bone health. They would not be force-molted or artificially light-triggered to lay eggs, and they would be allowed to live out their years.

Farms that come close to this exist now, their eggs sold at places like farmers’ markets for four, five, or six dollars a dozen. But imagine scaling this up to 83 billion eggs every year. Now imagine 147,000 layer hens (a single barn at Vande Bunte Eggs) or the 295 million alive at any time in the United States running around, many more if we allowed all those birds to live out their lives. There would need to be far more land for far fewer hens — and those hens would lay far fewer eggs. Right now demand for eggs of that type is very low, so they are fairly inexpensive. Most people buy eggs produced by the megafarms for one third that price. Imagine how expensive those humanely raised eggs would be if they were the only ones available.

So let’s consider a compromise. Halve the space, then halve it again: one square foot per bird, the UEP minimum requirement for cage-free hens (battery-caged hens have sixty-seven square inches). Maybe they can’t run and fly, but they can still walk and flap. Let’s allow debeaking (necessary in that space) and early death but still give them sunshine and dirt. Maybe we insist they be covered under the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act (though legal attempts at this have so far failed, the most recent appeal having been dismissed for lack of standing, and since the hens themselves cannot sue, there is little hope of their ever being covered). Maybe we insist on more accountability and on public access to farms. Maybe we put in place a “good stewardship” training program for egg farmers, many of whom, after all, believe even the enriched cages an unnecessary luxury.

But if we wanted to do so much as the least of these — sunshine, say — we’d have to persuade not only the egg industry but also the federal government, which is taking steps toward restricting, not encouraging farmers to allow their birds outside. (Industry farmers argue that providing outdoor access to birds increases the risk of salmonella and other diseases because the birds may come into contact with wildlife, although the biggest outbreaks have been from caged birds.) To this end, the FDA has proposed new guidelines for the Egg Safety Rule that recommend the hens’ outdoor areas be surrounded by fences or a “high wall” and covered by netting or “solid roofing” — walls and a roof. Some state governments, such as Michigan’s, are even moving to outlaw backyard chickens.

Meanwhile, the UEP released a study arguing that even the most restrictive cage-free indoor facility, if federally mandated, would cost $7.5 billion for farm conversions, plus $2.6 billion in annual increased consumer costs, plus nearly 600,000 more acres of cropland for the hens’ feed alone (cage-free hens eat more), not counting the extra land needed to house the birds themselves.

I watched an undercover video of such a cage-free barn: a tremendous warehouse awash with crowded hens as far as the eye could see. An electric gate ran around the sides of the barn, giving the birds a shock whenever they touched it. At one point the workers needed to urge the hens to one end of the barn. The workers lined up and began making loud noises, shouting and clapping and waving enormous sheets of metal. The terrified hens fled screaming to the other end of the barn — many thousands of them, all running over one another and knocking one another down and flapping and shrilling.

Any way we look at it, it seems impossible for the egg industry to meet all our demands: happy hens, cheap eggs, an unlimited supply. The question of the cages turns back on us: How much are we willing to pay? How much are we willing to make the hens pay? If we continue to eat eggs at the current rate — a historically unprecedented high number — the hens who produce them will be treated horribly.

In the conference room at Vande Bunte Eggs with Knecht and Karcher, the conversation is winding down. I’m getting ready to say goodbye and still I haven’t seen a battery henhouse. I pretend to study my list of questions, pen in hand, then say one final time, “So where are we on seeing a traditional barn?”

To my astonishment Rob sits back and says, “If you really want to see a traditional house, I can show it to you.”

We walk over, put on fresh biosecurity suits, and Rob opens the door. “I hope I have a job after this article comes out,” he mutters. Why is he letting me see it? “It gives you an idea of what we’re going away from,” he says. “The past.”

I go into the barn and the past is very present: the crud, the pit, the tight tiny cages. I can feel every breath, and I swat at flies as I walk. The pit seems even worse than it was in the video. The grime is thick, and it hangs from the feeders and cages and belts like icicles. I can barely see the cages under it. In one area it coats the wall. At the end of each row, it gathers in eight-foot-high statues, covering over the end of the A-frame. The air burns my lungs and my chest tightens. I walk down the long aisle of hens. The cages are much smaller than those in the enriched barn and are packed with birds. I count six hens to a cage, most of them balding on their necks and backs, their wings featherless. The birds crouch in their cages, their combs poking out through the bars. After all the time I’ve spent hearing about it, watching video of it, reading and thinking and asking questions about it, the battery barn feels almost holy to witness. Such a monstrous thing we have constructed out of wire and cement and steel, so huge you can’t see the other end, so filthy you can hardly breathe, stuffed with living beings for which we are responsible.

In June 2013, a California commercial egg farmer contacted a woman named Kim Sturla and said he had 50,000 spent hens ready to be rendered. She could come pick up as many as she liked. Sturla is the executive director of Animal Place, a sanctuary for farm animals in a quiet valley in northern California. For the past four years she has been contacting egg farmers and letting them know that she will take their spent hens off their hands, as many as she can manage, on the condition of two-way confidentiality. She told the egg farmer she could take 3,000 birds, the second-largest number she has so far rescued. She and a team of volunteers rented trucks and drove to the egg farm. In two days they carefully packed up the hens. Three thousand hens were too many to find homes for on the West Coast. An anonymous donor paid to charter a cargo plane and fly nearly 1,200 of them across the country to New York.

This flight seemed to strike a chord in the public imagination because it was reported that week in USA Today, the New York Times, and the Guardian. Twelve hundred hens in an airplane, bound for a better life, a man-made migration, a quixotic crossing. The hens landed, and from there they spread out, various sanctuaries claiming them, splitting them up, and taking them home.

A hundred of these hens wound up not far from me, at Sasha Farm Animal Sanctuary, in Manchester, Michigan. I went to see them, driving the opposite way that I’d gone to Vande Bunte Eggs, though also through farmland and small towns. I pulled up a gravel road and left my car at the end of a dirt drive. I walked past fields of cows and goats to a trailer at the side of the path. Christine Wagner, the assistant director, came out to meet me. “At first they didn’t want to go outside,” she said, as we walked over to the barn. “They were clumping together in groups, so piled up we were afraid they’d suffocate. It took them about a week to completely stop doing that.” When I arrived, they were not clumped together. They were pecking, preening, and eating. They were walking in and out of the barn, gathering in the doorway to spread their wings in the sunshine. They were dust-bathing in the straw, picking at vegetables left outside for them. A few sat in the shade of the trees.