From the air, Ubari looked exactly like the pitiful Saharan frontier town it is. Squat, unpainted cement buildings jutted from the southern reaches of the Libyan desert like a child’s scattered blocks. There were a few emerald-colored farms, irrigated by the man-made river — a vestige of Muammar Qaddafi’s grandiose plan to pump water from the aquifers and make the desert bloom. Most of Ubari was beige, however, with a latticework of windblown rifts in the surrounding sand dunes. At ground level, I would soon discover, the place looked just as bleak.

But beneath Ubari’s tumbledown exterior hid a turbulent truth: the town was a key transit point in a complex weapons pipeline that stretches across Africa and the Middle East. Libya shares 2,500 miles of border with six different countries, and its southwestern desert is a major trafficking zone, with drugs, migrants, fuel, and food flowing through en route to further delivery points. Smugglers living in Ubari or making regular stops there trade all these goods, but weapons are the local specialty.

Empty crates that once contained Soviet-era SA-7 MANPADS, at an arms depot in Ga’a, Libya © Bryan Denton/New York Times/Redux

There is no shortage of merchandise. During the Libyan revolution of 2011, NATO’s bombing campaign targeted Qaddafi’s arms depots — and since these facilities were seldom more than partially destroyed, they became gold mines for weapons foragers.

When I arrived in Ubari last fall, I had already visited one such site, a military base just a few miles outside Sabha, the largest city in southern Libya. The military base, Jebel Bin Arif, was completely abandoned. A stubby cement wall did little to protect the eight battered buildings. There was no glass left in any window frame that I could see; the guardhouse down the road was empty. The militia commander showing me the site ticked off a list of what he expected was still inside: “Rockets, land mines, ammunition, explosive stuff.” The only thing that stopped us from going inside one of the buildings was self-preservation — unexploded ordnance left behind by airstrikes could be anywhere.

Weapons have always existed on the African black market, of course. But Qaddafi’s stockpiles are more sophisticated than what was previously on offer. Among the most worrisome weapons now in circulation are man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS) — shoulder-fired missiles that can be used to take down a commercial airliner during takeoff or landing, when the plane is at lower altitudes. The United Nations estimates that Qaddafi had 20,000 MANPADS, of which about a quarter have been rounded up by a U.S.-funded program. Still, as a senior U.N. official in Tripoli put it: “If you’re determined to bring a plane down, does it matter if there are twenty thousand or one?” He added that MANPADS were only part of the problem. “It’s open shopping,” he said. “A warehouse. The whole of Libya.”

One September afternoon last year, I was sitting in a house in Ubari with a group of men, including my translator and yet another militia commander I had just interviewed about smuggling routes, when the power went out. Inside the small house, the air became heavy. We discussed how long the outage would last — probably four hours, my companions decided, and they began comparing Ubari’s blackouts with those hitting the capital.

An open door allowed some light into the room from outside, but with the curtains drawn, it was dim and getting dimmer as the sun moved toward the horizon. The militia leader had told me that there was someone else I should meet, so we waited, shifting around on the synthetic velvet of the floral-print couches, our sweaty clothes sticking to our skin. Finally, two men shuffled in.

One of them was a short, skinny kid with a shaved head who wore a black button-down shirt and black dress pants. He couldn’t have been older than twenty. The other was taller and looked to be in his early thirties. He was boxy, with intense brown eyes and a scraggly beard, and he wore a gold galabia, the traditional Arab kaftan, over black track pants. The two sat down and began picking at a plate of yellow apples, plums, and pears.

“You’ve come to the end of the world, the end of Libya,” the older one noted, eyeing me. “Is it safe for you here?”

“I hope so,” I said.

“The weather today is very, very nice,” the kid said. The weather was in fact horribly unpleasant, with temperatures over one hundred degrees. In the Sahel, a band of semiarid desert spanning the breadth of the African continent, the heat flares at midday, and by afternoon lethargy settles like a weight on everyone’s shoulders.

“Okay, let’s talk,” the kid said, and the two lit up Chinese cigarettes from the younger one’s pack. They exhaled in unison. I explained that I’d come to Ubari to understand the weapons-smuggling network and the people who work it.

“Most people will tell you the story that they like,” the older one said.

“Nobody will tell you the truth,” the kid said.

Both spoke English, the kid as if he’d grown up on the South Side of Chicago, in an idiom honed by American films and rap lyrics, which he referenced frequently and with mistakes. The older one spoke haltingly, with an Arabic lilt. He paused as he searched for words. At one point, I offered to have my translator interpret, but he protested. “You know why I like English language?” he asked, lighting another cigarette. “It is a poor language. When people use it, they say the truth. You don’t have liars.”

I explained that during my time in Libya, I’d encountered many liars.

“I’ll give you the first honest information. He’s one of them,” the kid said, nodding at his companion. “That’s all I can say.”

“We start,” the older one announced.

During my time in the Sahel, I had quickly learned never to ask for anyone’s name right away. Smugglers are cautious by nature, and everyone was suspicious of an American running around plotting black-market transit points on a foldout map. So it was only later that we were formally introduced. The older man’s name was Mohammad Hassan, and for almost three years, he had been selling weapons to anyone who would pay for them.

The road between Ubari and the central Libyan town of Waddan is circuitous, winding among the mountains, boulders, and dunes that rise on either side of the crumbling asphalt. In early 2011, this was still Qaddafi country. But when NATO struck a weapons-storage compound in Waddan that spring, Hassan decided to ransack whatever stockpiles the planes had missed.

Hassan, who grew up in an Ubari slum, is a Tuareg. This nomadic, non-Arab tribe had traditionally inhabited the Saharan desert. But during the 1970s, after a devastating drought in the Sahel and persecution in Mali, large numbers migrated to Libya. Qaddafi eagerly enlisted the Tuareg in his military machine. His refusal to grant most of them citizenship, however, meant that many, like Hassan and his two younger brothers, remained not only poor but stateless.

Since just a single warehouse in Waddan had been hit directly, the rest were open for plundering. On his first raid, Hassan grabbed what he could: a Soviet-made PK machine gun, 14.5-mm anti-aircraft guns, AK-47s, hand grenades, MANPADS, and a land mine. He loaded them into his car and drove to a cave in the nearby mountains, hiding the weapons before coming back for more.

At the time, Hassan told me, nobody cared. If you took a gun, it was your gun. If someone hid guns and you saw where they were hidden, you could steal them — it was a free-for-all. The payout would be good: a PK sold for 12,000 dinars, about $10,000. Well worth the risk, he thought. Hassan decided to leave his weapons hidden in the cave and to take only a few samples back to Ubari. If he ran into any government checkpoints, he would shout “Long live Qaddafi!” and hope for the best. But on that first trip, no one stopped him.

Back in Ubari, he had little difficulty unloading his merchandise. “I have this one, this one, this one,” he told potential buyers. “When do you want to take it? This one? How many pieces?” His first sale was to locals; the second set of buyers came from Algeria.

“During the revolution, the machine was working,” Hassan explained. “Ubari became big shop.” Rebel groups from Morocco, Mali, Niger, Sudan, and Chad sent buyers to the frontier town, he said. Hassan didn’t make too many inquiries about who the end users were. But he knew they were foreign.

When Hassan made a deal, he brought the buyers to a location near Waddan to claim their purchases, then pilfered more stockpiles. “I saw this like an adventure,” he said. For added protection, he wore a military uniform and pretended to be a soldier. He obtained fake military paperwork as well, but the additional precaution wasn’t really necessary. During the civil war, Qaddafi had dangled the possibility of full citizenship for Libyan Tuareg in order to maintain their loyalty, and the promise of good pay lured in additional tribesmen from Niger and Mali to fight as mercenaries. As a result, the Tuareg made up a large part of the loyalist forces and could move around the country with impunity. “Nobody cares about you,” Hassan said. “If people see that you have army clothes, they don’t ask you much.”

After a few weeks of raiding NATO targets, Hassan moved on to bigger things: he went to Tripoli, which was still under Qaddafi’s control. Despite its 1.5 million people, the Brother Leader’s capital operated like a village. (Because of tribal and regional segregation, in fact, the whole country generally seems smaller than it is — a place where six degrees of separation rapidly shrink to two or one.) Hassan kept careful track of which frontline military units were rotating back to the city and was quick to make connections with his fellow Tuareg.

By this time, he had accumulated identity documents from three different military units, including papers from the brutal Khamis Brigade, which was led by one of Qaddafi’s sons.1 He had no difficulty strolling into the abandoned schools or open-air camps where the returned units had set up their bases in Tripoli.

Once inside, he made inquiries about excess armaments. With Qaddafi’s front line in chaos, soldiers were allowed to take any weapons they needed to fight — and they soon learned that these items fetched handsome prices from people like Hassan. “No one was looking very closely,” he told me, “because this is a war. This is death. These are hard people.” Hassan made such transactions easy, going so far as to wire proceeds to the soldiers’ families via the local equivalent of Western Union.

Hassan also found Nigerien Tuareg employed by two different farms outside the city, who were willing to store the weapons until he was able to ship them south. Having spent some time in Niger himself, he had no difficulty gaining their trust: “Now you are in Libya and you miss your country. I speak your language and I know your places — maybe I know your street, okay? We are humans, I can make a deal with you.”

In August 2011, he heard that Tripoli was about to fall to the rebels. It was time to cut his losses and return to Ubari. By now, Hassan had decided to get out of the business of stockpiling the weapons himself. Instead, he would act as a middleman, connecting sellers (most often militia leaders with excess weaponry) to buyers, and facilitating cross-border transfers through his network of contacts. That was how he made his living when I met him. Times had changed.

Libya had changed as well, he noted. Qaddafi was gone, shot to death after being found cowering in a drainage pipe, and new ringleaders had emerged. “Now we make our business and say, ‘Allahu Akbar!’” Hassan said. He laughed, and then grew serious. “Maybe I am a bad guy, but I tell the truth.”

Even under Qaddafi, the task of controlling Libya’s borders was poorly coordinated, with competing departments spread across several ministries. There was no defense ministry: instead the army’s branches reported separately to the Brother Leader through the Interim Defense Committee. And for the dictator, access to smuggling routes and goods was a way to buy off political opposition and to reward tribes for supporting the regime. In a 1988 speech, Qaddafi actually endorsed smuggling as an example of populist ingenuity:

You may think that black markets are negative. On the contrary. As far as we are concerned as revolutionaries, they show that the people spontaneously take a decision and without government make something which they need: they establish a black market because they need it. . . . What are black markets? They are people’s markets.

After the 2011 revolution, as the state’s mediation fell away and new players began to enter the marketplace, violence erupted over control of the southern smuggling routes, particularly between Libyan Arabs and the country’s two minority tribes, the Tuareg and the Tebu. Today, as warring militias bring the northern half of the country to the brink of collapse, intermittent fighting has broken out in the south as well.

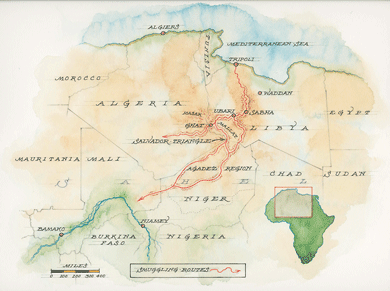

Surprisingly, however, conflict between the two minority groups is minimal — they continue to abide by a territorial agreement signed in 1875. The Tuareg oversee most of the southwestern border with Algeria and parts of Niger. The Tebu, an ethnic minority of roughly 350,000, take over from there: their turf stretches along Libya’s border with Niger, Chad, and Egypt. The two groups also tend to maintain separate markets (although I met people who operated in both). The Tebu are said to excel at smuggling people, food, and fuel, while the Tuareg control drugs and weapons.

An arms shipment leaving Ubari may be destined for any number of countries, including Algeria and Mali. But in many cases a convoy will wind its way around the Masak Mallat mountain range, cross the Salvador triangle — a lawless territory one Tuareg described as “terrifying and controlled by gangs” — and then head south to Niger.

If Libya is ground zero for weapons smuggling, Niger is a key country of transit. Its vast, Tuareg-dominated northern desert allows plenty of space for suppliers and buyers to exchange contraband. The irony is that this perpetually unstable nation, which has experienced four coups, seven republics, and three armed Tuareg rebellions since gaining its independence in 1960, is also America’s newest ally in the international “war on terror.” In January of last year, the two countries signed a status of forces agreement that paved the way for a small detachment of U.S. troops to enter Niger. It also allowed the United States to fly drones out of Niamey, the capital, with the goal of keeping an eye on the Sahel.

Niamey is the sort of city that resolutely refuses to stick in one’s memory. Although the population is estimated at well over a million, there are few obvious street signs and only a handful of buildings taller than ten stories. Its shops, stalls, and low-rise structures bleed into one another, while the sand-packed streets are crammed with camels, motorbikes, beat-up Toyota taxis, and the gleaming four-wheel-drive vehicles favored by international aid workers.

It was in Niamey that I met a smuggler whom I’ll call Omar.2 In the courtyard of a house owned by a Tuareg notable, Omar and I sat on folding chairs with a map of Niger spread out between us. For more than an hour, he pointed out the routes used by traffickers. Then, suddenly, he clammed up.

“I know that you are a journalist and an intelligence agent,” he said. The midday sun baked the orange sand, and Omar squinted — perhaps looking for affirmation of his claim or because sunbeams had penetrated the garden hedges that surrounded us. “Myself, I’m very happy that you are asking me questions,” he said. But he explained that it was dangerous to cooperate with Western governments, because the drug and weapons traffickers had close ties to the local authorities. “You will leave me and not protect me,” he said. “That’s why I don’t want to help.”

Later, on the terrace of the Grand Hotel, a faded remnant of the French colonial era perched above the Niger River, I met a senior military official who immediately confirmed the collusion between the government and the smugglers. As dusk settled over the water and the mosquitoes hummed, he explained the practice of issuing official passes, known as chargé d’affaires cards, to known traffickers. “Soldiers, if they see the pass, they are afraid,” he told me. If a soldier is bold enough to make an arrest, the card-carrying detainee is invariably released.

Traffickers, the official lamented, have so efficiently infiltrated the state that they control much of the government of the volatile northern region of Agadez: the military governor, the justice officials, the generals. “We catch them many times with drugs and weapons,” he said, “and send them to the police. We are surprised to meet them again. It’s like you’re fighting against something that will never disappear.”

More than elite collusion or ideological motivation, the Sahel’s smuggling networks thrive on disenfranchisement and poverty. These are the forces that generate so many eager recruits — men such as Tarek, whom I also encountered in Niamey. A twenty-five-year-old Tuareg from Sabha with curly hair and a solemn expression, he worked as an armed escort on smuggling convoys.

Like many of the industry’s support workers, Tarek had a relative in the business, who specialized in providing such escorts. Tarek had begged for the gig, which typically paid the equivalent of between one and two thousand dollars per trip. “Money is about the number of cars,” he told me, referring to the convoy. “The less cars, the more risk, so the more money.”

Tarek said that he doesn’t always know what he’s guarding. Indeed, the escorts aren’t generally briefed on the cargo loaded into the Toyota 4x4s, which race through the desert at top speed to dodge interference by military patrols or opportunist gangs. The escorts simply follow the smugglers’ vehicles. By one commander’s estimate, it takes ten hours to move a shipment from southern Libya to a dropoff point in northern Niger. Sometimes weapons are off-loaded in the desert and their coordinates sent by satellite phone to the next convoy, which will pick them up and convey them to another group’s area of control.

With so many Tuareg in the rotation, it’s hard to get consistent work. When we met, Tarek hadn’t found a gig for some time. He had also served three months in a Sabha jail after a Tebu militia stopped his convoy mid-route, impounded his truck, and seized the cargo.

Ahmed, a Tuareg from a village in Mali, told me that he’d also come to Niamey in search of escort work. It was not going well. As the only male in a large and impoverished family, he was under pressure to earn some cash.

“I don’t consider myself a smuggler,” Ahmed told me. “Personally, concretely, I’m an escort. But I’m not stupid. Sometimes it’s drugs, but I’m sure those loads were weapons.”

As it happens, weapons flows have changed in the past three years. In 2012, when Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and other extremist groups took over northern Mali, bulk shipments poured in that direction, slowing when the French drove out the invaders. Since then, the flow has shifted to Egypt, Gaza, and Syria. Weapons from Mali have also been resold back into the Libyan market, especially now that rival militias are fighting tooth and nail for control of Tripoli, Benghazi, and crucial infrastructure such as oil refineries and the capital’s airport. But if there’s one group that always needs such merchandise, Hassan told me, it’s the Islamist extremists. “Every time they make new fighters and they make new wars, they lose weapons,” he said. The French, he noted, had killed many Al Qaeda fighters in Mali. “They lost many people and many weapons. He lose the weapons, he needs the weapons again.”

Al Qaeda has plenty to spend. Over the years, the organization has made millions from illicit cross-border transactions — particularly from kidnapping Europeans across the Sahel and holding them for ransom. According to a New York Times investigation, AQIM collected at least $91.5 million in ransom payments between 2008 and 2013. With such a bulging war chest, Al Qaeda and its affiliates can offer at least double the market rate for escorts and weapons.

Extremist groups have also been linked to other kinds of trafficking, including drugs. Mokhtar Belmokhtar, a former commander of AQIM and now the leader of Al Murabitoun, earned the nickname “Mr. Marlboro” for running a cigarette-smuggling empire earlier in the decade. Hassan and others confirmed that the extremists were highly competent when it came to business: they had a web of representatives in all the southern Libyan cities, including Ubari.

“Al Qaeda, they are people who have many faces,” Hassan said. “You know this small animal that changes its color?”

A chameleon, I volunteered.

“Yes, this is Qaeda people,” he said. “Ahmed Ansari, this is the first man in the Qaeda. He has a school, a religious school — he uses this name. But exactly, this is the place for Al Qaeda. You know Ansar Dine?”

Ansar Dine, which means Defenders of the Faith, is a Tuareg extremist group that worked with AQIM and another group, the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), in northern Mali. They were driven out during the French intervention but have vowed to return, and they continue to carry out attacks on U.N. and Malian troops. (On October 7, an Ansar Dine rocket attack on a U.N. encampment killed one peacekeeper, only days after a MUJAO ambush killed nine others.)

According to Hassan, Ahmed Ansari worked with Ansar Dine, sending them weapons and recruiting locals in Ubari. “I make a deal with them sometimes. I’ve seen them work, and I know the people that know them,” Hassan said. Just this summer, he told me, Ansari supposedly had bought some MANPADS.

This was not the first time I had heard Ansari’s name. It seemed to surface in accusatory whispers every time extremists were mentioned. I heard Ansari had spent time in Mali, that he had worked with radical groups in Libya’s turbulent east, that he had funneled foreign fighters through the city on an extremist superhighway that stretched through the Sahel and North Africa into the Middle East. I was even told that Belmokhtar had married Ansari’s sister — a rumor passed along by an influential Tebu in Ubari, who asked that I keep his name secret for fear of retribution.

Ansari was said to have at least two military bases inside Ubari. There was also a rumored training camp outside of town, located in an oasis where a cluster of trees grew to an unaccustomed height above the brush. Trying to sift fact from mythologizing fiction, I asked Ramadan Salah, a Tebu commander of a border-control unit in the Shield of Sahara militia, to give us a tour.

Salah picked up me and my translator from the former Qaddafi villa where the Tuareg had been hosting us. At the wheel of his white Hyundai Santa Fe, Salah was a giant, towering above me even when seated. Every time he laughed, which was often, the gap between his ivory teeth was visible. He was dressed in a white turban and a neatly pressed orange galabia, which gave him a regal look.

Pulling away from the gate, Salah exclaimed: “The place you are sleeping is danger, they will kidnap you!”

“We were fine,” I said.

“Maybe they didn’t know you were there!” Salah replied, still chuckling.

In fact, there had been some joking at dinner the night before about how much my head would net the local militia. The guests, a few Tuareg elders and at least one drug lord, ultimately decided that Americans were worthless, since the U.S. government refuses to pay ransom for hostages.

Salah turned onto Ubari’s main road and within minutes we passed the white walls of a military compound on the left. Salah slowed the car. The red, black, and green revolutionary flag was painted on the base’s metal gate, and the number 315 was scrawled in black paint on the side wall. “This Qaeda!” he shouted, grinning and pounding the wheel with his broad hands.

We continued to Ubari’s central roundabout, which surrounded a shabby market of tarp-covered stalls, and Salah turned left. We passed government buildings and the faded storefronts of one-room buildings selling food and automobile parts.

“This Al Qaeda!” Salah cried again, jabbing the wheel. He nodded at a white-walled structure with green accents, which also had 315 scrawled on the front. “Danger! This is Ahmed Ansari’s second base,” he proclaimed as he circled back, driving slowly by the compound. The top floors were burned out, and through the metal gate I counted three bearded men in white galabias at the entrance, but saw nothing that would specifically indicate a terrorist stronghold.

“Don’t worry! You have security!” Salah said, laughing, and gestured toward the back seat, where an FN assault rifle, a Belgian weapon most frequently used by NATO allies, rested on the floor.

Of all the militia members I met in southern Libya, Salah seemed the most at ease with his illicit income — derived, in his case, from border-patrol duties. “I’ve spent almost three years at the border,” he said. “If anyone is telling you they prevent anything, they are lying.” Salah extorted the equivalent of eight dollars from each migrant he intercepted en route between Niger and Libya. The take was steady. He owned two brand-new Toyotas, and inside his spacious house in the middle of an empty patch of desert, he had a massive flatscreen TV with a satellite dish, a Jacuzzi sunken into the floor of the bathroom, and a sizable heavy-arms cache hidden in his bedroom closet. (“If the government pays attention,” he told me, “then we will be citizens. But they are not doing that, and we need to survive.”)

We headed north on Ubari’s main road toward Ansari’s alleged training camp. As we exited the city gate, I could already see the tall trees in the distance — a strange sight in a land of sparse, knee-high scrub. We were about six miles from Ubari when we passed the camp’s closed white gates. Even the guard window was shuttered. “For sure, they are inside,” Salah decided. “I hate Qaeda!”

We made a U-turn and drove past again. This time, a camouflage-patterned Toyota pickup coming from Ubari turned into the gate. “That’s Abdel Hakim Belhaj’s car!” Salah declared, after seeing the stenciled logo on the driver’s door. Belhaj was an Islamist commander in Tripoli, who has subsequently tried to reinvent himself as a businessman and political player. He was imprisoned by MI6 in 2004 for his links to Al Qaeda but has denied any affiliation with the organization. Salah turned to me with a broad, beaming look that required no interpretation: I told you so.

The problem was that everyone called everyone else Al Qaeda — if the organization wanted to file for copyright infringement, Ubari would be the place to start. The brand cropped up all the time as shorthand for any Islamic extremist group, including those, like Ansar Dine, that were officially unaligned with the global franchise. But on the ground in the Sahel, armed militias look more like a patchwork quilt than an international terror monolith. They emerge whenever there’s a viable opportunity, and alliances in the desert seem to last only for as long as they are useful, and not a minute more.

Today, two influential extremist groups are at work in eastern Libya; confusingly, both of them are called Ansar El Sharia, which means Partisans of Islamic Law. At least one was reported to have been involved in the attack that killed U.S. ambassador Christopher Stevens in Benghazi on September 11, 2012. The same group (or groups) spent much of the past summer battling Libyan special forces in Benghazi, even as a third party, a former general gone rogue named Khalifa Haftar, joined the fray, leading his self-proclaimed national army against the Islamist militias.

“It’s an unholy alliance,” a Western diplomat in Tripoli told me about the network of jihadi groups, months before he and his colleagues were hastily evacuated from the city. “It’s a your-enemy-is-my-enemy temptation.” Earlier on, he argued, Libya’s extremists had been embroiled elsewhere; many North African fighters had joined the Syrian insurgency. The rise of the Islamic State would, of course, continue to attract recruits. But now the battle was also raging at home, where the combatants kept reshuffling themselves into ever new configurations.

And what about AQIM? The group got its start during the Algerian Civil War in the 1990s, when Islamists battled the military government after a brutal crackdown. It became part of global Al Qaeda in 2006. Six years later, in another of the shape-shifting alliances peculiar to the region, AQIM joined with Ansar Dine and MUJAO to hijack what had originally been a Tuareg-nationalist rebellion in Mali. They managed to occupy most of northern Mali for ten months, imposing an extreme version of sharia law that punished offenders with stoning and amputation.

In January 2013, the French drove the Islamists back into the desert. There is some dispute, however, about whether the defeat truly broke the back of the alliance. “The French intervention has had a few successes,” says Rudolph Atallah of the Atlantic Council, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington, D.C. “But these guys still exist, and they do whatever they want, whenever they want to. They continue to expand over a very large geographic space, and now they’re interrelated across borders. All they need is constant access to weapons.”

Meanwhile, as much of North Africa is convulsed by extremist violence, the United States continues to fly its drones out of Niger and across the Sahel. The value of this intelligence remains questionable. Many people I spoke with pointed out that America can scarcely police its own borders, let alone keep close tabs on the vast, porous boundaries among Niger, Mali, Libya, and Algeria.

“We use surveillance,” the Western diplomat in Tripoli told me. “But it’s very limited.” He cited as obstacles the huge geographic area and the lack of strong governments in the region. As for southern Libya in particular, it was a virtual blank. “We don’t really know what’s going on down there.”

It was late afternoon and our tour was over when Salah parked his car in front of Eissa Dudu’s house. Dudu is an excitable sliver of a man, his white turban almost swallowing his pointy face and glasses. He works for a human rights organization on minority issues, and his sitting room was festooned with traditional hand-painted leather Tuareg handicrafts. Dudu was eager to discuss the increasing threat of Islamic extremism in Libya, but when I asked about Ansari, he initially had no idea who I was talking about.

“Ah! Sheikh Ahmed!” he finally said, shaking his head. “Before, he was with those groups, now he is against those groups!”

As Dudu recounted, Ansari’s friends and family had brought him back from the darkness of extremism about a year earlier. “He changed his mind and now he’s against them, he’s against killing innocent people,” Dudu said. “He is teaching young students who don’t have fathers or mothers or are homeless.”

Would I like to meet Ansari? Dudu volunteered to invite him over. “This is an exam. If he refuses to meet you, I will cross him off my list,” he said, swiping his palms together. He picked up his phone and made the call. “He will come!” Dudu said, so we waited.

It was dark outside when Ansari ducked through the doorway, flanked by a handful of younger men whom he introduced as his students. Minutes before his arrival, Dudu had asked me to put on a head scarf. “Just as a sign of respect,” he mumbled, almost apologetically, as he offered me one of his wife’s veils.

Ansari was towering, his face wrapped in a white tagelmust, the traditional Tuareg turban that usually leaves only the eyes visible. Ansari had pushed down the fabric to expose the lower half of his face, and his bushy, graying beard strained against the bottom folds.

“We welcome you to Ubari,” Ansari began as he settled, cross-legged, onto the brown carpet. “Whatever you need, we are ready to provide you. Any place to visit, we can take you to this place and return you. You will have no problem.” He smiled broadly. It was charming.

The first thing Ansari told me was that he was no longer in charge of the 315 militia. He said that he had stepped down six months ago, though he still facilitated communications between 315 and the ministry of defense when needed. “This is not a special group or a special militia. All the members of the katiba are officially in the Libyan army. If you would like to visit them, it’s easy. I can arrange it.”

Dudu’s wife served coffee in tiny white porcelain cups, the thick brew fragrant with spice. The cup looked like a toy in Ansari’s mammoth fingers. I asked him why so many people thought 315 was an Islamist brigade.

“These are rumors,” he replied. “People are not accepting the new Libya, they are not accepting the revolution. Those who are saying bad things about this katiba, they are Qaddafi loyalists.” Ansari launched into a tortured explanation of a contested local election and the sore loser who had spread these absurd rumors. “For a long time, I have been warning the locals about extremist Islamist groups, and they threatened me, and they tried to kill me. I have no relationships with those groups.”

I asked Ansari whether he had relations with Libyan politicians who were thought to be aiding Islamist extremists, as Dudu had suggested to me earlier.

“I have no relations with those groups, before or now,” he said.

I looked around at my companions. Dudu said nothing. Salah was in repose on the other side of the room, watching the muted television, so I asked again.

“The locals here know me, I was never a member of those groups,” Ansari repeated. I looked around again. Everyone was blank-faced, Dudu nodding along in support. I asked a third time.

“I’m a moderate Muslim and I’m against the terrorists and extremists,” Ansari insisted.

There was silence in the room as I pondered what to say. Less than an hour earlier, Dudu had told me that Ansari had been reeled back in from the precipice of extremism. Now the sheikh was denying any connection, past or present, to extremist groups, and nobody — not even fearless, straight-shooting Salah — said a word. After what felt like an eternity, I asked to visit the 315 katiba, even though the next day was Friday, the Muslim day of rest.

“Okay, yes, in the morning,” Ansari said. “My message to the international community is that we are looking for good relations, and we find in Islam the guide for how we can live together. If you need any information about Islam, we can provide you books.”

Without prompting, my translator explained that I had read the Koran in college, and Ansari seemed pleased.

“If you have someone like you, but she is Muslim, I’m going to marry her,” Ansari said. The room cracked up, and I asked Ansari whether he was married.

“I have one, but I can take another,” he replied.

“This is only joking!” Dudu piped up in English, eager now to chime in.

My time in the Sahel had been like stumbling along a hall of mirrors. I could not confirm who anyone was, nor many of the things that they had told me: all I could verify was that Libya was awash in weapons and that the smuggling machine was working. The old channels for contraband, fed by poverty, corruption, opportunism, and official neglect, were churning with renewed vigor and better merchandise than ever before.

For the disenfranchised border communities of the Tebu and the Tuareg, Libya’s postrevolutionary project was far away and had yielded little. Why would these local profiteers throw in their lot with the national government, such as it was? Of course their business — shuffling lethal merchandise between buyers and sellers who were themselves willing to change sides at a moment’s notice — was essentially amoral. Yet these players did operate by their own code of ethics. (Hassan, for example, told me that he avoided drug trafficking because he found it a less moral trade than weapons: if he got involved, God would “punish me too much in hell.”) It was hard not to admire their skill, ingenuity, and entrepreneurship. On the other hand, the final outcome of their transactions, once the goods reached the end users, has frequently been horrific.

The assault on Algeria’s In Amenas gas plant in January 2013, orchestrated by Belmokhtar and his brigade, was the largest terror attack to use verifiably Libyan weapons; the attack left forty foreign hostages dead after a four-day siege. Meanwhile, a U.N. study released in February of this year reported the discovery of Libyan weapons caches in Tunisia, Algeria, Mali, Niger, Chad, the Central African Republic, Somalia, and the Gaza Strip, where smuggled MANPADS, quite likely of Libyan origin, have been fired at Egyptian and Israeli aircraft alike, destroying one of Egypt’s military helicopters in January. This deadly merchandise has fanned the flames of the ongoing catastrophe in Syria, contributed to the implosion of Libya itself — and there is even speculation that Libyan MANPADS, originally exported to Syrian rebel groups, have ended up in the hands of the Islamic State. Meanwhile, Qaddafi’s arms depots, the source for so much of this weaponry, remain almost completely unguarded. Indeed, an earlier U.N. program set up to secure the forty-seven designated Libyan Ammunition Storage Areas managed to access just four of them before the organization fled the country this summer.

Equally ineffectual is the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership, which the United States has been promoting for almost a decade. The idea is to work with governments across the Sahel to share intelligence and fight extremism, but the program seems to have had little impact. Neither has the EU’s border-training initiative in Libya, nor the U.S. program to buy up Libyan arms, to which the federal government committed $40 million in 2011 (although it did manage to take those five thousand MANPADS out of circulation). And in January, the United States proposed a $600 million package to help train Libya’s new army, which includes a shipment of M4A4 carbines and small arms ammunition. That’s right: the American government was planning to send Libya more assault rifles.

If the Sahel is a primary front in the “war on terror,” I saw no evidence that Western governments are winning. Instead, it felt like the international community was wringing its hands and huddling inside its armored compounds, playing catch-up with extremist and rebel groups. After spending eight weeks in the Sahel, I wasn’t sure what the international community could do about stemming the flow of weapons, especially given the apparent collusion of government officials.3

For my own part, I couldn’t confirm the truth about Ahmed Ansari — who, according to some sources, has been spearheading the more recent violence around Ubari. He did not return my phone calls the morning after our meeting, and since I was leaving town that afternoon, I never saw the 315 bases. When I told Hassan about my conversation with the sheikh, he shook his head. “He’s a liar. He make his hands like this,” Hassan said derisively, pressing his hands together in mock prayer.

“Maybe nobody would tell you,” Hassan reasoned. “They don’t believe you. Everybody thinks you’re CIA or something like that, so he won’t put himself in danger. But I know you.”

I explained how everyone in the room who had previously condemned Ansari just sat there in silence, expressionless, while he contradicted their claims. I asked how that was possible, how everyone could be so good at lying.

“How can you live with the lion and a chicken and a wolf in one house?” was Hassan’s reply. “If you want to live in our jungle, you need to use your head.”