Discussed in this essay:

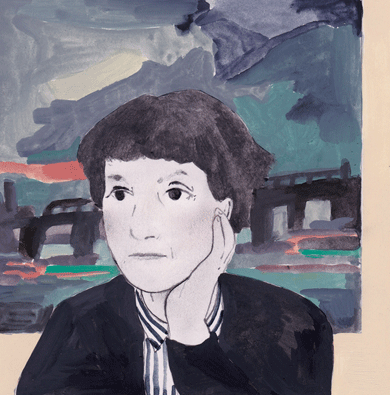

Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life, by Hermione Lee. Knopf. 512 pages. $35.

In Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life, Hermione Lee has written the kind of biography that probably every writer dreams of receiving: respectful, fair-minded, conversant with the pertinent literary references, drawing on all extant sources, and largely, the reader senses, in the dark.

Lee herself is aware of the problem. On the first page, she warns that her subject, best known in America as the author of The Blue Flower, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1998, was “cryptic”; in the last chapter, she is still wrestling with Fitzgerald’s “reticence, evasiveness, and secrecy.” Accident explains some of the obscurity. Many of the photographs and papers that documented Fitzgerald’s early life were lost in 1963, when a houseboat she lived on sank, and fame didn’t touch her until she was eighty, by which point many witnesses had no doubt either forgotten about her or died.

But there are signs, too, that Fitzgerald would have been hard to get to know under any circumstances. The letters of hers that have been published are unrevealing, and if Fitzgerald ever had a confidant, that person hasn’t surfaced. One associate reported, “You never quite knew what she really meant.” When an old friend, on renewing contact, asked about her late husband, Fitzgerald told him, “He just died.” Journalists found her so well defended that Lee is often reduced to cataloguing the commonplaces Fitzgerald fobbed off on them. Lee even resorts to reading between the lines of reviews that Fitzgerald wrote. She hints, for example, that Fitzgerald may have been skeptical of the “amiable drunk” that James Stewart played in the 1950 film Harvey because she had grown impatient with her own husband’s alcoholism. One admires Lee’s resourcefulness, but one wonders whether Fitzgerald took her secrets to the grave. It’s possible, of course, that the darkness is merely apparent — that there is simply nothing to see other than a grandmother with a weapons-grade intellect who waited until her sixties to start publishing novels that were compact, hilarious, and for the most part tragic.

Fitzgerald came by a taste for privacy naturally. When her father, the longtime editor of the British humor magazine Punch, was asked to write a memoir, he declined to supply more than a title: Must We Have Lives? The trouble is that if we must, and if people insist on reading about them, then one wants to know a little more. Why did Fitzgerald wait until her sixties to write? Was it her marriage that delayed her blossoming? Or was she hesitant to step out of the shadow cast by her famous father? What did she think about her husband’s alcoholism? The failure of his career sometimes left her and her children homeless and short on food. Why didn’t she turn to family and friends for help? Why are so many of her fictional characters and biographical subjects homosexual, either by avowal or implication? And what about her religious beliefs? Many of her books hinge on questions of faith, but Fitzgerald was no Cardinal Newman, eager to dilate on those “two and two only absolute and luminously self-evident beings, myself and my Creator.” God was another topic she said little about.

Lee poses many of these questions, and it’s probably to her credit that where the evidence is insufficient, she has too much tact to speculate about answers. In the end, her best sources are Fitzgerald’s novels, biographies, and essays; Lee’s continual recourse to them, and her sensitive, detailed descriptions, have the effect of suggesting that Fitzgerald may actually have been that chimerical beast: the writer who can only be approached through her works.

Sometimes the charisma of a nuclear family has such a strong pull that children of the second generation grow up hoping to qualify as honorary siblings of the first, and something like this seems to have been the case with Fitzgerald. The charm of her father and his three brothers began in childhood, to judge by The Knox Brothers, her 1977 group portrait of them. The young Edmund Knox, her future father, edited and illustrated the family newspaper, The Bolliday Bango. Dillwyn Knox “saw” sums without having to “do” them. Wilfred Knox maintained a private museum called, and containing, Bits of Old Churches. And Ronald Knox, the baby of the family, threatened to teach himself Sanskrit and Welsh despite a family rule against languages that no relative could understand. One thinks of the boast of the preppy-misfit hero of Wes Anderson’s film Rushmore: “I saved Latin.” Indeed, Ronald contributed a serial in Latin to The Bolliday Bango.

And when the Knox brothers grew up, one of them did save Greek — the Greek of a minor, bawdy Alexandrian satirist, at any rate. Out of mangled fragments of papyrus, Dillwyn pieced together a definitive text. Using the same skill set during World War I, Dillwyn deciphered a German code, having noticed that one of Germany’s radio operators seemed to be using it to transmit poetry (Schiller, as it happened). Edmund, for his part, contributed light verse to Punch before becoming a staffer and then, from 1932 to 1949, its editor. Wilfred took vows of celibacy and poverty, and advocated for the Anglo-Catholic movement within the Church of England, despite his somewhat eccentric manner. (“Your dog’s chewing the seat of my trousers, Canon,” a gardener once informed him. “So I see; I don’t feel tempted to follow his example,” Wilfred replied.) Ronnie may have been the most prolific. In addition to becoming, in 1917, the most famous convert to Roman Catholicism of his generation, he penned detective stories, memoirs, Christian apologetics, a fantasy reinterpretation of Sherlock Holmes that doubled as a joke about German Biblical criticism, and a new translation of the Bible.

Lee points out that Fitzgerald had little to say about the Knox sisters, one of whom, under her married name, Winifred Peck, became a successful novelist. Perhaps Fitzgerald coveted her spot in the family tree? Lee also suggests that Fitzgerald played down what Lee calls “the ambivalent sexuality of three of the brothers.” By today’s standards, perhaps she did, but in the mid-twentieth century, such information was ordinarily conveyed in public writing by means of suggestive details, and Fitzgerald was fluent in the code. To readers also in the know, her meaning must have been fairly clear when she wrote that, after losing their religion, “Dilly and [John] Maynard Keynes had calmly undertaken experiments, intellectual and sexual”; that Ronnie was a devotee of the sentimental fiction of R. H. Benson and was led into Roman Catholicism in part by his love for one of his students at Oxford; and that Wilfred went through a period of “hardly ever speaking to a woman at all,” apart from relatives. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is much less forthcoming. (All four Knox brothers have entries in it, which would probably be a record if it weren’t for the Mitford sisters.)

Lee finds the key to the Knox brothers, and to The Knox Brothers, in an item in the index, which Fitzgerald compiled herself: “Emotion at war with intellect.” It was a conflict that Fitzgerald also felt, judging by the life story that Lee has assembled.

Fitzgerald was born on December 17, 1916, in the bishop’s palace in Lincoln, where her maternal grandfather resided. (Her paternal grandfather was also a bishop, as was one of her great-grandfathers.) Her family called her not Penelope but Mops, Mopsie, or Mopsa. Her father, after being shot in the back in France, came home from World War I and moved his wife and two children to a village in Sussex, where they were surrounded by struggling artists and writers but had, Lee reports, “no electricity, no telephone, no refrigerator, no washing machine, no nearby shop.” For a child, it was idyllic, and in later years, just the memory of it could help Fitzgerald fall asleep. She had a brother, three and a half years older, but one of her favorite games was solitary: gathering rose petals into small heaps, naming the heaps, and then burying them.

In 1922, the family moved to Hampstead, northwest of central London. Lee describes it as “part-bohemian, part-genteel,” and it was to be the closest Fitzgerald came to native ground. There she and her brother edited the family periodical of their generation, IF, or Howl Ye Bloodhounds, and on trips into London proper she bought children’s rhyme sheets at the Poetry Bookshop, run by Harold Monro, a homosexual and alcoholic whose romantic commitment to the arts became for Fitzgerald a lifelong fascination. At eight, she was sent away to boarding school. She hated it, but she excelled, and in 1935, as her mother was dying of bowel cancer, she aced the entrance exam to the women’s college at Oxford that her mother had attended. Her family sent her to France for the summer; reports differ as to whether she made it home in time to tell her mother goodbye.

Fitzgerald’s father had lost his mother at age twelve, and the loss, she wrote in The Knox Brothers, had left him with a temperament that “might, at times, have been mistaken for coldness.” Of the death of her own mother, when Fitzgerald was eighteen, she said little, but she did observe that it was years before her father could bring himself to say her mother’s name again. At Oxford, Lee reports, Fitzgerald took notes in a volume of Spenser’s poetry that her mother had annotated while a student there.

Fitzgerald was a hot number in college. She ran in a set who called themselves Les Girls, and a campus magazine dubbed her “Our Penny from Heaven.” Lee likens Fitzgerald’s romantic life to something out of an Iris Murdoch novel. After graduating, she rented an apartment in London with her brother, and as World War II began, her father arranged for her to write movie reviews for Punch. Later, she took jobs at the Ministry of Food and the BBC. During the war, a bomb landed in her bedroom. A mine attached to a parachute had to be removed from her street. At the BBC, she fell in love “with someone very much older and more important, without the least glimmer of a hope of any return,” she admitted years later in a autobiographical sketch. In Human Voices, her 1980 novel fictionalizing the affair, the young heroine succeeds in winning her egocentric, married, middle-aged beloved, as Fitzgerald in real life doesn’t seem to have done. One of Lee’s sources believes that the man in question ran the BBC Recorded Programmes Department, as the character modeled on him does in the book. “Everyone fancied him,” the source tells Lee. Indeed, in Fitzgerald’s novel, a second man at the BBC is as devoted to the heroine’s beloved as she is, and his attachment is at least as one-sided. Fitzgerald doesn’t say that this attachment is romantic, but the calamity that ends the book would have a deeper resonance if it were. One wonders whether Fitzgerald originally intended an unconventional love triangle but had second thoughts.

It was also during World War II that Fitzgerald met her husband, Desmond Fitzgerald, who had enlisted in the Irish Guards and was studying for the bar. Not much is known about their courtship, but this isn’t so surprising. When a Penelope Fitzgerald character falls in love, consciousness of it often surfaces in the form of annoyance over the attendant loss of self-control, while tenderness, if there is any, remains unexpressed. The couple were married in August 1942, in a Catholic ceremony officiated by Penelope’s uncle Ronnie, and Desmond sailed for North Africa in February 1943. After his return, more than a year later, he sometimes woke up at night screaming, and friends noticed that he drank heavily.

The Fitzgeralds had a son in 1947 and settled in Hampstead the following year. Desmond worked as a criminal barrister until 1950, when a right-wing Catholic press baron hired him to edit a literary journal. Penelope contributed essays and cowrote many of her husband’s editorials, but the journal was a commercial failure, even though, under the couple’s editorship, it published work by Louis MacNeice, Muriel Spark, Joyce Cary, L. P. Hartley, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Cyril Connolly, J. D. Salinger, Bernard Malamud, and Alberto Moravia. By the time it shut down, in 1953, the Fitzgeralds had three children to support, Penelope’s connections to the BBC had frayed, and Desmond had been away from law so long that it was difficult to return, though he tried. In 1957, they abruptly moved to Southwold, a small town in East Anglia. Their neighbors in Hampstead guessed that it had been a while since they had paid their rent.

Southwold sits on the coast, and in The Bookshop, Fitzgerald’s 1978 novel drawing on her experiences there, misery seems to inhere in the landscape, which might equally well be called a seascape:

The North Sea emitted a brutal salt smell, at once clean and rotten. The tide was running out fast, pausing at the submerged rocks and spreading into yellowish foam, as though deliberating what to throw up next or leave behind, how many wrecks of ships and men, how many plastic bottles.

In the alembic of Fitzgerald’s art, the bleakness becomes exhilarating. The book opens with the image of a heron struggling, while in flight, to swallow an eel slightly too large for it — “The indecision expressed by both creatures was pitiable,” Fitzgerald writes — an emblem of the protagonist’s attempt to open a bookstore in a town that distrusts and resents such an improving enterprise. Like most autobiographical novels, The Bookshop is probably as much about the time when it was written as about the time recalled. Fitzgerald seems to have been fictionalizing at least two selves: one who survived poverty and isolation in the provinces at the end of the 1950s, and a later one, at last writing a serious novel in the 1970s, who can be heard in the heroine’s moments of resolve, as when she wonders “whether she hadn’t a duty to make it clear to herself, and possibly to others, that she existed in her own right.” An even younger self may be represented by a minor character, a young woman who works in the BBC Recorded Programmes Department and is in love with an attractive, effete, amoral, and somewhat feline coworker. He has disappointed the young woman, though the novel doesn’t specify how, and the older heroine, observing him, doubts that he has any real ability to love. “His emotions, from lack of exercise, had disappeared almost altogether,” Fitzgerald writes.

Malice in the service of observation provides much of the pleasure of The Bookshop. Once the heroine opens her store, for example, publishers’ agents try to foist on her “novels which had the air, in their slightly worn jackets, of women on whom no one had ever made any demand.” When the shop starts a circulating library, the sniping over first dibs on new books turns vicious. “Some may feel that they have the right to read first about the late Queen Mother,” a patron sniffs. It’s like Cranford but existentially ruthless, and at first the heroine doesn’t quite recognize the hatred around her. “She blinded herself, in short,” Fitzgerald writes, “by pretending for a while that human beings are not divided into exterminators and exterminatees.” Herons and eels, in other words. Sometimes one isn’t the heron.

In the novel, Fitzgerald imagines herself as a widow, but life had not been so neat. During the week, Desmond spent nights at his mother’s house in London to be near his legal work, and drank; on weekends, he traveled to Southwold, where he drank some more, and he and Penelope quarreled. He doesn’t seem to have been earning much. In 1960 or 1961, Penelope decided that the family needed to move again — perhaps another flit from creditors — and she chose a retired coal barge that floated, when it did float, in the Thames, near London’s Battersea Bridge. The vessel leaked; the living quarters were small, cold, and damp; electricity was sporadic; and the toilet could only be flushed when the tide was receding. She began to teach child actors at a stage school, later recalling with indulgence the “fierce electric thrill of rejection” that the children manifested for all things academic, which reminded them that their performing careers would likely be ephemeral. (She would capture the merriness of the young narcissists, and the hatred and louche attention they won from their elders, in her 1982 novel, At Freddie’s.) She soon moved on to a school for girls from wealthy families and to a tutoring establishment that Lee describes as “raffish,” where A. S. Byatt was a colleague. In all, she would end up teaching for twenty-six years.

Money was scarce on the barge. According to Fitzgerald’s children, potatoes were carefully portioned out at dinner, and one of the family’s frequent meals was stew out of a can. Sometimes they caught their mother eating blackboard chalk. Husband and wife now slept apart, and Desmond often came home late from his drinking. One night, he stumbled and fell onto the riverbed at low tide, cracking his skull. In 1962, he formed a habit of pocketing checks made out to his colleagues, endorsing them to himself, and cashing them for drinking money. He was caught, convicted, and disbarred, and his son denied knowing him when a classmate pointed out an article about his disgrace in the newspaper. To cheer Penelope up, a man from a neighboring boat, whom she later described as “an elegant young male model,” took her to Brighton for a day. “We went on all the rides,” she recalled, years later, with gratitude, “and played all the slot machines.” The man returned alone to Brighton a few days later and drowned himself.

Could anyone’s life have been this grim? Fitzgerald herself seems to have felt a need to edit. When she put her neighbor, the model, into Offshore, her 1979 novel about life on the river, she had no scruples about saying that the character, named Maurice, made a living by picking up men in a nearby pub, but she couldn’t bear to have him kill himself. She couldn’t bear to kill off the character based on Desmond either, though Lee has discovered that in early notes she intended for him to fall overboard and for his cries to go unheard. At least in Fitzgerald’s reimagining, life remains worth living for the inhabitants of the houseboats, thanks to their humor and sense of community, complexly interwoven in a shared awareness of “a certain failure, distressing to themselves, to be like other people.” Maurice isn’t afraid of the sort of thing that might frighten a landsman, such as the law or the elements, Fitzgerald explains. “The dangerous and the ridiculous were necessary to his life,” she writes, “otherwise tenderness would overwhelm him.” In Fitzgerald’s world, it’s tenderness that one has to watch out for. “It’s his own fault if he’s kind,” one of the heroine’s two daughters says to the other, about someone whose good nature they’re exploiting. “It’s not the kind who inherit the earth, it’s the poor, the humble, and the meek.”

“What do you think happens to the kind, then?” her sister replies.

“They get kicked in the teeth.”

Offshore was to win the Booker Prize in 1979, to the consternation of many journalists, one of whom suggested to Fitzgerald on television that the judges must have made a mistake. Evidently the journalists were expecting the winning novel to be more uplifting. “Don’t you think it must deliver something of importance to everyone?” a BBC host asked Fitzgerald. “No, I don’t,” she replied.

The Fitzgeralds’ barge sank in 1963, and Penelope and the children had to live in a homeless shelter for four months. A year later, Desmond took a job as a clerk in a travel agency, which he would keep for the rest of his life, and the family moved into subsidized housing in South London. Fitzgerald’s personal low seems to have come in 1966, when she became so distraught over her son’s decision to marry a young Spanish woman that she left notes in an appointment diary that verged on suicidal. “If you find a person who is really alone in the world, they would be a test-case for an action (eg, suicide) which hurt no-one but themselves,” read one. Thirteen years later, the words would reappear, slightly altered, as a line of Maurice’s dialogue. She weathered the depression, however, and by the end of the 1960s, she and Desmond had settled into affectionate companionship. Lee even reports that together “they watched the Eurovision Song Contest with a passion.”

In 1971, old age caught up with Fitzgerald’s father, who noticed, as he went, that “there’s an awkward thing about dying — one gets so little practice.” The same year, she began her first book, a biography of the artist Edward Burne-Jones. While she was writing, Desmond’s health started to fail, and in 1975 he was diagnosed with bowel cancer, the same illness that had killed Fitzgerald’s mother. On the day her biography was published, Fitzgerald complained that “nobody cares.” It’s a petty thing to have said under the circumstances, though I suspect most writers will sympathize. Still, it brings up the delicate question of what Fitzgerald was like as a person. “Geniuses are not nice people,” says Byatt, one of several who found Fitzgerald hard to get along with. “Her spikes were sharp,” recalls a student. “She could nip,” says a cousin. Her children report that she didn’t hug or kiss, and that she cheated at the board game Ludo with them, cheated at croquet with Desmond when he was ailing, and even cheated with her grandchildren at picture lotto. A former president of PEN claims that a pair of her tights were stolen by Fitzgerald while they were sharing a hotel room, though Lee seems unsure whether to believe the story. None of these are felonies, and it should be noted that Fitzgerald’s two daughters and their husbands happily hosted her in their homes for years, but it does suggest that any impression of her as soft and vague was probably mistaken. Several of Fitzgerald’s heroines announce themselves by candidly disliking music that is being poorly performed. She may have felt that the honest recognition of discord was one of her strengths.

Desmond died in August 1976, and the following year, during a trip to China, Penelope began to write The Bookshop in the back of her travel diary. She had previously written a mystery that satirized the Tutankhamen exhibition, during a month that Desmond had spent in the hospital recovering from a colostomy, but The Bookshop was her first serious novel, and the first to draw on her own past. It marked an epoch. The rest of her life would be happy, productive, and, no fault of Lee’s, a little boring to read about. She continued to teach until, in 1987, she could afford not to. In between stints in granny flats in the homes of each of her daughters, she lived in a London attic for seven years — a spell of what Lee refers to as “late freedom.” She started writing for the London Review of Books. And every couple of years, for two decades, she published a new novel or biography, making the Booker short list four times.

One of the few mysteries of her later years concerns one of those books, a 1984 biography of Charlotte Mew, a minor poet of the early twentieth century. Before Fitzgerald wrote it, her novels drew on her own life; afterward, they staged scenes in times and places distant from her own, including Russia in the throes of revolution and Germany at the dawn of Romanticism. Homosexuals, a sly presence in the early novels, are by and large absent from the late ones. Lee rightly calls the Mew biography a hinge, but Mew is not a figure that many would consider pivotal. Though she was acclaimed by Thomas Hardy, Walter de la Mare, and other connoisseurs of her day, she never quite found her audience as a poet, and as a lesbian, she was, though sometimes aggressive, never successful. “I had to leap the bed five times!” one object of her affection complained, of efforts to escape her. Mew was burdened by a hapless family, including two siblings with schizophrenia and a sister who made her feel guilty by toiling at painting with even less success than Mew had at poetry. When the sister died, in 1927, Mew seems to have experienced a strange relief. “Now she can never be old, or not properly taken care of, or alone,” she wrote a friend. The following spring, Mew swallowed Lysol — “the cheapest poison available,” Fitzgerald observed.

Lee thinks Fitzgerald wrote the book out of pity, and sees affinities but no biographical points of identification between author and subject. Fitzgerald was not always the success that she eventually became, however, and there is something Mew-like — doomed and brave — about a line that Lee has found in one of Fitzgerald’s teaching notebooks from 1969: “I’ve come to see art as the most important thing but not to regret I haven’t spent my life on it.” Fitzgerald believed that visual artists were compelled to create by a need to exorcise images that haunted them. Did she write about Mew to exorcise a story?

Fitzgerald’s own explanation of the transition was matter-of-fact. She feared that the parts of her life she hadn’t yet tapped were too sad. “The temptation comes,” she wrote, “to take what seems almost like a vacation in another country and above all in another time.” In her 1986 novel Innocence, her first attempt at a researched setting, the clicking of the gears is still audible, and the machinery never quite comes to life. But Fitzgerald’s last three books are marvels, and whenever I’m tempted to parrot Henry James’s indictment of the “fatal cheapness” of the historical novel as a genre, they stop me. James complained that imagining oneself into the consciousness of an earlier era is so difficult, and so little likely to be appreciated by most readers, that historical novelists almost always resort to papering over their failures with a decoupage of period-appropriate details. I’d add that imagining a past free of one’s presentist assumptions requires so much intellectual labor that most historical novelists make the mistake of giving it their whole attention, forgetting that the most interesting thing about the consciousnesses of the past, while they were being lived, was that they were changing. Most historical novelists construct something too easy to know, too definite — no longer a mystery, as a living consciousness always must be, even to itself.

Fitzgerald didn’t make these mistakes. Her heroes and heroines never quite understand themselves, or one another, no matter how hard they try. She was able to catch moments of transition, perhaps because she understood that to a responsive consciousness they may feel as much like loss as like opportunity.

She returned again and again to the question of the soul, which seemed a focus for these changes and mysteries. She handled it gingerly, touching it only through layers of irony. In The Beginning of Spring (1988), the owner of a printing house watches the blessing of an icon. He is struck by the reverent attention of one of his employees, who had previously asserted that “soul and body were like steam above a factory, one couldn’t exist without the other,” and begins to doubt his own doubt. Perhaps, he thinks, “I have faith, even if I have no beliefs.” In The Gate of Angels (1990), an aspiring particle physicist defends the soul because he belongs to a university club called the Disobligers’ Society, which requires its members to argue positions they don’t believe in, and the intellectual exercise feels to him “like hanging upside down or breathing the wrong element.” A confused older professor in the audience thinks he’s in earnest. The poet-hero of The Blue Flower (1995) believes that only souls exist and that bodies are no more than shadows, destined to fall away in some future apocalypse, but he falls in love with a twelve-year-old girl who thinks that life after death sounds silly. “What insolence,” he writes in his journal, “what enormity.”

One can’t quite figure out what Fitzgerald herself thought of the soul, but perhaps that’s as it should be. True novelists don’t think in syllogisms, after all, and it’s motion, rather than structure, that gives a sense of life. One does get the impression, however, that the soul, as Fitzgerald understood it, is rather more in the plight of eel than of heron.