I just squandered two or three precious should-be-working hours trundling around music-streaming sites looking for “The Banks of Sweet Italy,” my all-time favorite Incredible String Band song. Dotty, druggy, sublime ye-olde mimsy: you will no doubt remember the arpeggiated fake-medieval daftness of it all. Finger bells and tootlings. Ladies and unicorns. Pointy handmade shoes. Heavenly treacle for wizard ears!

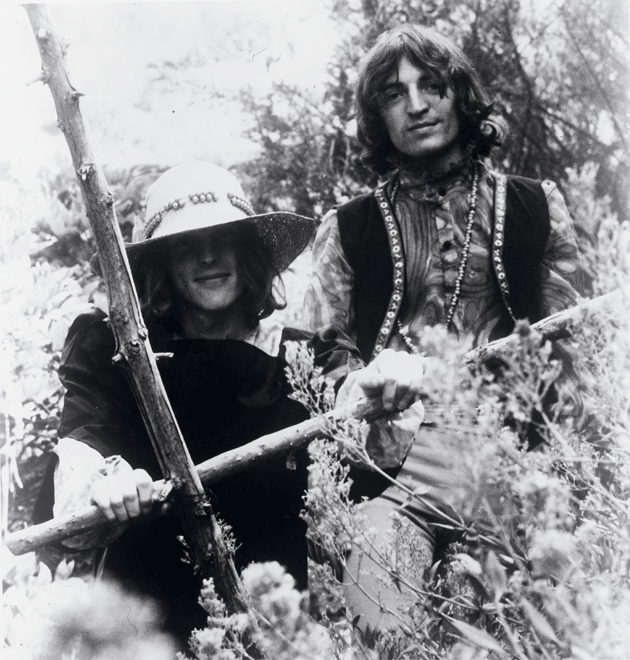

When I finally lay cybergauntlets on the song, it turns out to be from Earthspan (1972), one of the group’s later, somewhat decadent albums, made when Robin Williamson — the band’s most visionary, droll, and profusely gifted member — and Mike Heron, his coleader, were starting to bicker. Blond hippie girl Licorice McKechnie (Robin’s girlfriend at the time) is first up, delivering the opening verse in a shrill, eldritch, teeth-on-edge soprano:

And must you go, my flower, my gem,

My laughter and my hope of joy,

To follow fortune through all the world?

May luck pursue you, my darling boy.

She yields, some will say blessedly, to recorder and lute-plucking, followed by Mike and Robin and Malcolm Le Maistre — suitably boomy — singing a nutty Knights Templar refrain:

The sun shines bright in France.

Yellow it shines on high Barbaree.

Oh, be my light of day

Tarry not long on the banks of sweet Italy.

Then, finally: darling Robin alone, in gleeful banshee mode, whirling forward into his signature vocal arabesques. Haverings, stork cries, labyrinth sounds, mystic ululations that envelop the listener like a cloud of Scottish fairy dust — he’s liquid, primeval, the guardian spirit at the heart of the maze. Yes, it’s 2015. Old friends have vanished in the mist. Countless species have become extinct. But here I am again: At One with the Great God Pan.

Is there anything more shaming than doting on the electrified English folk-rock of the late Sixties and early Seventies? It’s taken me, I confess, a dreadfully long time to come to terms with it — to acknowledge that I adore, nay, have always adored, the whole tambourinetapping, raggle-taggle mob of them: Pentangle, Fairport Convention, Sandy Denny, John Renbourn, Shirley Collins, Bert Jansch, Martin Carthy, Steeleye Span, Maddy Prior, Richard and Linda Thompson, Lindisfarne. I still venerate Jethro Tull and its leader, the psychedelic flutist Ian Anderson, unforgettable for his dandified overcoat, harelike skittishness, and giant comic aureole of red beard and frizzy hair. It’s like admitting you’d rather go to the local Renaissance Faire than hear Mahler’s Lieder at Wigmore Hall.

One is cruelly dated by one’s doting. The British fad for switched-on folk reached its apogee somewhere between 1968, when the Incredible String Band released its sitar-laced masterwork, The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter, and 1978, the year that the lissome but likely inebriated Sandy Denny, former lead singer of Fairport Convention, died of blunt head trauma after falling down a flight of stairs. Yes, one capered and twirled through it all. Alas, one is now fairly eldritch oneself — positively rime-covered.

I became a fan in the early Seventies, partly out of some romantic “Englishness” (British parents) and partly out of a Tolkien-influenced countercultural interest in ballads, alchemy, ancient magic, Celtic standing stones, and the literature of the Middle Ages. I was a bookish grad student, living alone in the Upper Midwest, yet oddly obsessed with Sir Gawain and dowsing wands. Long Lankin, Matty Groves, and Black Jack Davy — not to mention any number of ladies on milk-white steeds — somehow became my imaginary posse. Hearing Steeleye Span’s rollicky up-tempo rendering of “Little Sir Hugh” — Child Ballad No. 155 — on a radio show one morning was, I recall, a watershed moment:

Mother, mother, make my bed

Make for me a winding-sheet

Wrap me up in a cloak of gold

See if I can sleep

That Little Sir Hugh (speaking here) has just had all the blood drained from his body by a lamia is part of the charm.

Nothing quite the same, I found, existed in North American rock of the time — not in the heraldic, folk-guitar-spangled sound of the Byrds, or in pleasantly cheesy one-offs like Simon and Garfunkel’s “Scarborough Fair.” While still revered, perhaps, by New Age witches now residing in Wiccan assisted-living covens in Oregon and Big Sur, terminally wyrd favorites of mine such as Buffy Sainte-Marie’s doomy “Reynardine — A Vampire Legend” or Pentangle’s “Lyke Wake Dirge” were hardly emblematic of American popular taste. The United States, alas, was signally lacking in shires and sprites and elf-knights, not to mention mummery and morris dancers.

The heyday of true British folk-rock was brief. Along with Sandy Denny, other leading musical lights had disappeared from view by the late Seventies. Shirley Collins, the innovative balladeer behind the hugely influential album Anthems in Eden (1969), damaged her voice and stopped singing. Richard and Linda Thompson, one of the most unusual and mesmerizing vocal partnerships of the late twentieth century, became devout Sufis and later divorced. The Incredible String Band broke up in apparent acrimony in 1974. Robin moved to California, where he became active in the Church of Scientology. Licorice went with him, though she subsequently vanished into the Arizona desert. (Internet ghost trails suggest that after renouncing Scientology — as Robin seems to have done also — Licorice wished to evade L. Ron Hubbard’s vengeful myrmidons and assumed a new identity.)

Musical tastes had changed dramatically by then. Electronic pop and rock went in two antagonistic — yet both firmly anti-folkie — directions in the late 1970s: toward disco, rap, and urban dance music on the one hand (sexy, sleek, fun), and toward punk on the other (mock savagery, crashing chords, and taking the piss). My own, somewhat wistful, defection came around 1980, after I was mercilessly satirized by my neopunkoid quasi boyfriend Dick for hoping he might grok Richard Thompson’s dark and skirling live version of “Poor Will and the Jolly Hangman.” Yet as soon as I’d (reverently) laid down the needle, I had to snatch it up again — prompted by my companion’s hideously mimed display of convulsive writhing and retching. (I should have anticipated my folly: Dick had recently traded his pretty, bowl-shaped Botticelli haircut for one of clipped, David Byrne–style severity.) We had to wash out our ears at once with some bacteria-rich Iggy Pop and Sex Pistols. I later regained a mote of Dick’s respect because, unlike any other girl he knew, I actually owned several Ornette Coleman records and had started tiptoeing toward Alfred Ayler, Cecil Taylor, Anthony Braxton, and other thoroughly haute-arcane exponents of the jazz avant-garde. Such mandarin interests were enough to recall me, probationally, to the ranks of the maybe-elect.

But so too began my decades-long slide into musical pretentiousness: Cage and Webern, Harry Partch, rediscovered Baroque opera played on period instruments, obscure blues vamps, Renaissance polyphony, historic recordings from the decaying urns of forgotten French record companies, Ligeti études, Pauline Oliveros, Captain Beefheart, and Moroccan gnawa music — these became preferred listening. Manfred Eicher’s much-lauded German boutique label, ECM — notorious for its cerebral emphasis on the more severe strains of avant-garde chamber music (musique concrète, György Kurtág, Pierre Boulez) and stark, echt-minimalist jazz (mostly northern European) — became a go-to source for hardcore experimental stuff.

Yet life has its freaky surprises, and even kitsch of a long-gone era can suddenly — bizarrely — start pinging on one’s snob-radar. Take Robin Williamson. Yes, mon vieux, the golden-throated, once-and-future Ariel behind the Incredible String Band still makes records! The curly blond hair is an elfin silver now, but the voice remains intact — as Panlike and mellifluous as ever.

It turns out that after the Incredible String Band broke up, Williamson — who is now seventy-one and seemingly indefatigable (he still lives in California and continues to tour, with his wife and fellow musician, Bina) — carried on singing and recording for four long decades, most of them unremarked by the musical mainstream. But he has recently returned to view by way of four burnished and resplendent CDs, all of them on hallowed ECM. The most recent of these, Trusting in the Rising Light, was released in November. Like its forerunners, The Seed-at-Zero (2001), Skirting the River Road (2003), and The Iron Stone (2007), the new disc features Williamson, warm Scottish burr and all, declaiming over a growling, haunting jazz-folk accompaniment. In earlier recordings he riffed on the poems of William Blake, Dylan Thomas, Henry Vaughan, John Clare, and Walt Whitman. Here he sings and recites his own verses, vocalizes wordlessly, and improvises on Celtic harp and guitar to uncanny and arresting effect.

He is joined by several top-flight players from the experimental-jazz world — the most improbable being Mat Maneri, the quiet, mad genius behind what one can only call a seriously downtown, seriously daunting, post-post-post one-man string section. A brilliantly untethered improviser, Maneri can expostulate, seemingly effortlessly, on the five-string viola, electric six-string violin, and the baritone viola. I first came across him via the beautiful but hermetic recordings of his father, avant-garde saxophonist Joe Maneri (1927–2009), a renowned teacher of microtonal music at the New England Conservatory of Music. (Both Maneris, unsurprisingly, are represented in the ECM catalogue.) Joe’s microtonalism — reflecting a lifelong study of world music and non-Western scales — seems to have rubbed off on Mat: in the words of one critic, both father and son trade in a similar “slippery, space-filled alien blues.” Mat, in turn, has spoken of his artistic debt to Indian ragas, serialism, Baroque chamber music, and the atonal compositions of Elliot Carter.

Okay: I know it all sounds weird — like Queen Latifah singing Bartók. But adventurous listeners will be rewarded. Robin is still Robin — free and unabashed by the oddity of his material or his own throwback status, and in flagrantly glorious form. Maneri, meanwhile — one can almost hear him listening, E.T.-like, to Williamson’s ancient cadences — supports him in what gradually becomes an astringent and exquisite conversation. Though sometimes inclined in the past to the gushy and shambolic, Williamson here is bracing and austere. And Maneri, tracking the folkways, shows himself a man, warm-blooded and wise — not a space alien at all.

Literary types — especially lovers of English Romanticism — will take particular delight in Williamson’s late resurgence. The term “bardic” still gets thrown around a lot in college English classes, typically to refer to a preliterate, visionary, or divinely inspired strain in epic poetry. Homer — whoever he (or she) was — is usually cited as the first Western bard: a poet-musician who knew his archaic material by heart and performed (to lyre accompaniment) with incantatory gravity. For fans of Wordsworth or Coleridge or Blake, it is hard to see anyone coming closer than Williamson has to the “bardic mode” as reimagined by the great English Romantic poets of the early nineteenth century. He seems to channel the Muse directly. To hear him deliver, say, “The Four Points are thus beheld,” from Blake’s mystical poem “Jerusalem,” is to feel summoned to a peculiar and solemn attention.

But there’s a happy kind of respite here too — a gentle turn away from apocalypse. If living every bright and horrible twenty-first-century day is making you feel appallingly old all of a sudden — a sort of scarified, baby-boomer Methuselah — Williamson’s remarkable creative rebirth in what he calls the October of his life can be encouraging. The endgame, thrillingly, is not quite so endgamey as you feared. A so-called late period is possible, even if you’re a Scottish singing hippie who was once garlanded in wildflowers and the goofy radiance of youth.

And certain things are indubitably better when reexperienced. One of the unsung pleasures of encroaching senility, or so I’m finding, is how many things from the past suddenly reveal themselves as even more awesome than you thought they were the first time. The Four Tops, for example. Madame Bovary. Studebaker station wagons. Little baby rabbits. Schopenhauer. You’re not embarrassed by any of it anymore. The plastic seat covers. The pellets. The World as Will and Representation.

Rediscovering Robin Williamson — or someone like him — may in turn prompt further recalibrations. You drag out your old Incredible String Band albums and find in them countless marvels of Musical Genius Personified: ravishing melodies and colorful, polyphonic structures; an inspired use of non-Western instruments (tabla, oud, sitar); witty, not-half-bad lyrics (surely no worse than early Yeats and far less lugubrious); an overall effect of loose, lightsome, psychedelic joy in life. You begin to relish your new connoisseurship: you feel sagelike. Maybe aging, after all, is simply a new form of getting stoned? The Very Long Nap will come soon enough; for now, let these little floods of pleasure continue. Dear Licorice, that means you. Tarry not long on the Banks of Sweet Italy. We want to hear you again.