I reached the town of Maesteg, in Wales, where the weed was first reported in the wild, late in the afternoon. I had seen so much of it already that day, and in such calm profusion, that I was no longer sure what I was expecting to find in the place of its original escape. Since it breached the redbrick walls of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, in West London, at some point during the 1850s, Japanese knotweed has colonized pretty much every corner of the British Isles, but nowhere with more assiduity than the wet valleys and clean towns of South Wales. Many local people, particularly from older generations, swear that the plant, with its reddish, hollow canes and bowing stems of green, ovate leaves, has been there all along.

There was a playing field low in the valley, next to the fast-flowing river that runs through the town. I parked the car and stood on a bridge above the water, looking for signs of the weed. John Storrie, a curator of the Cardiff Museum who died in 1901, was responsible for the early sighting in Maesteg. In The Flora of Cardiff, published in 1886, he described around sixty foreign plant species that had gained a foothold in the lower half of Wales. Storrie found most of these exotics growing on heaps of ballast that had been dumped along the coastline, the jetsam of docking ships, but he noted that Polygonum cuspidatum (one of many Latin names that existed for the weed before biologists settled on Fallopia japonica) was “very abundant on the cinder tips” near the town, among the mines and darkened hills about five miles inland.

The knotweed is native to Japan’s volcanic fumaroles. It was born to be inundated by ash and poisonous gases for years at a time. The Welsh valleys of the late nineteenth century were a home away from home. In the 1880s, Maesteg was emerging from half a century of primitive iron production and was about to sink into a hundred years of coal mining. Across Europe, plant nurseries advertised the hardy newcomer as fodder for cattle; its canes a good material for matchsticks; its underground stems, or rhizomes, an effective agent for stabilizing sand dunes. It was, they promised, “inextirpable.” No one knows whether it was originally planted near Maesteg with some purpose in mind or arrived from somewhere else — as it usually does — by means of a wandering root. In 1992, scientists showed that just 0.7 grams of knotweed rhizome, a fingernail, can spawn a new infestation.

The weed entered Britain in a box of forty Chinese and Japanese plants that was opened by the clerks at Kew Gardens on August 9, 1850. Specimen number 34, between a tree peony and a fan palm, was labeled Polygonum sieboldii. It was a simple shrub, known in Japan as itadori, or “pain puller,” and was used in the preparation of medicinal teas. The crate had been sent to London by Philipp Franz von Siebold, a Bavarian doctor and ethnologist who dedicated his life to opening the closed nation of Japan to the world and trying to make money from the subsequent rupture. Following the botanical custom, he offered his plants to Kew in the hope that the clerks would reciprocate and send him some Asian stock that he would be able to sell from his nursery on the outskirts of the Dutch city of Leiden. But Siebold’s box wasn’t up to snuff. “On account of the bad selection he is written to, telling him that only six of them are probably new to us,” reads the clerk’s note in the archives.

Of those six, plant number 34 was (and remains) sterile — or, more specifically, the weed does not produce male gametes. Dug up outside Nagasaki, most likely by one of Siebold’s Japanese students, she survived the six-month sea voyage to the Netherlands and subsequent transplantation in the nursery at Leiden with no other means of regeneration than her rhizomes. This means that the weed now present in more than 70 percent of the 3,859 ten-kilometer recording squares of the British Isles is a single female clone. It is the same story in most of mainland Europe. With the exception of a few massive matings with her cousin, the less-intrusive giant knotweed, itadori has conquered by what biologists call “vegetative spread” alone. People who make a living killing itadori, most of them men, often describe the weed as the largest female organism on the planet.

When I first arrived in Maesteg, I wondered whether the town might have driven out the weed. Wales’s former mining communities tend to be forbiddingly neat. On the cusp of evening, ornamental flower baskets filled the high street, as did the home-bidding smell of Chinese takeout. A group of children, none older than ten, careered down a hill of silent, immaculate houses on their bikes, screaming with happiness. I did not see the weed at all until I spied an alley, down the side of Bethel, “a church in the community for our community,” where it was casually pushing over a wall.

As I explored, I began to see that the whole town, rising up the slope, away from the river, was crisscrossed with other strangled back-routes. Maesteg’s external appearance was trim and organized, but its heart was full of knotweed. In the fading light, I chatted with a couple of dog walkers, who spoke with amused annoyance about the almost supernatural power of the plant, which they knew from their gardens. Later I encountered stranger, stronger reactions.

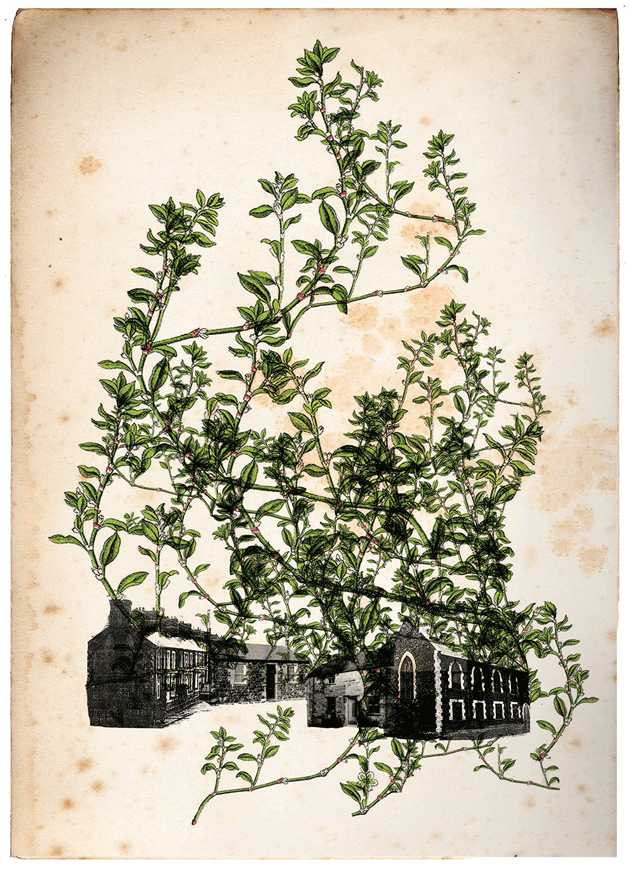

“Fallopia japonica & x bohemica, Swansea, Wales, U.K., 2005,” by Koichi Watanabe, from his series Moving Plants. Work from the series will be on view in December at The Third Gallery Aya, in Osaka. Courtesy the artist and The Third Gallery Aya, Osaka.

A powerful-looking man named Richard, with a black eye and a tattoo of thorns, showed me where he had just dug the weed out of his back yard. All that was left was tired earth and a browning string of bramble. He led me down a lane that was becoming a green tunnel, and pointed out a corrugated-iron shed that was almost buried inside the weed. He had a small trailer and seemed to be moving a lot of stuff out of his house. His young children had nowhere to play. “It’s heartbreaking,” he said. The weed was a monster.

Just a few yards on, however, I came across a middle-aged couple who had never stopped to wonder what the stuff growing all around them was. We were in a chamber of knotweed, one wall of which had been poisoned and flattened by a neighbor, allowing a view of the hills outside the town. I tried to explain that Maesteg was one of the first places that the weed got out. They asked whether the plant was rare, and whether it might be worth some money.

It was almost dark. I was due to spend the night with my father-in-law, who lives a couple of towns over from Maesteg, across the hills. I set off driving, but the road that I was planning to take was closed, forcing me into a detour that began to seem interminable. As night fell across the unfamiliar landscape, I struggled to distinguish the names of Welsh hamlets that flashed past on the road signs and clustered unintelligibly on my map. brynmenyn. aberkenfig. bryncoch. abergarw. bryncethin. To my surprise, the road emerged on a ridge — and I realized that I was high up — before it slid down into the valleys and the undergrowth again. The darkness, pressed against the car, felt quite foreign. I became disoriented, making guesses at turnings. Along every road I took, like bands of murky stars, the knotweed seeds glowed the same.

The first canes in Maesteg, which cropped up on slag heaps at the edge of the blackened town, were only a prelude to the main event. In South Wales, it was the deindustrialization of the region in the second half of the twentieth century — the earth movings, the fiber-optic layings, the retail-park raisings — that allowed the weed to really take control.

I saw this for myself in Swansea, Wales’s second city, which has been for decades now overrun. Sean Hathaway, who heads Swansea’s campaign against the weed, showed me around places where it is not supposed to grow but does anyway: through the heavy asphalt along the seawall, along the city’s sandy, salty beach. Officially, Swansea has around 250 acres under knotweed: 62,000 metric tons of alien biomass. But there hasn’t been a proper survey for years. Hathaway, a nimble, chuckling man who spends his days scrambling over root-threaded walls and down green, weed-blocked passageways, told me that after fifteen years of conflict he sensed that the battle in Swansea had now reached a stalemate. Each year the city poisons a few hectares, and each year the plant gains new ground elsewhere. Its stems grow up to four inches a day in the summer, cracking through roads, undermining buildings, filling in riverbeds. “It’s a bit like the Somme, really,” he said. “No one going that way, or the other way.”

“Fallopia x bohemica, Swansea, Wales, U.K., 2005,” by Koichi Watanabe. Courtesy the artist and The Third Gallery Aya, Osaka

There are places, however, where the weed has now taken such hold that its removal is impossible to contemplate. Hathaway took me to the site of an old quarry, not far from the city center, where the plant’s prodigious root structure was holding up a hillside. If the weed were removed, the land would fall into the road below.

We left his white Ford pickup and climbed into the vegetation. After a few yards the sounds of traffic were buffeted to nothing, and all I could see was the back of Hathaway’s checked shirt, framed in an enveloping wall of leaves. There was the odd bit of rubbish (thieves in Swansea have been known to fence their goods in knotweed thickets), but the character of the jungle lay in its monotony. It was late September, when the weed is in full vigor and heavy with seed, and all we could see was a stillness of canes, mulch, and last year’s leaves.

Up close, itadori’s leaves are the size of young children’s faces. They hang in their thousands from tubular, glabrous stems that stand twelve feet tall and emanate in groups from heaped, brown mounds known as crowns, which serve as the weed’s carbohydrate store in winter. Hathaway and I fell silent. The characteristics that make invasive plants and animals such a fundamental threat to the planet’s biodiversity — their desert monocultures, their boring, uncanny vitality — are impressive to behold in the flesh. “All it does is grow,” said Hathaway after a while.

He uncovered a nest of woody rhizomes that were as thick as wrists. They can stretch for twenty feet and are adapted to lie dormant in the ground for years at a time, in case the land above is destroyed by an eruption. “All of this knotweed is bits of von Siebold’s,” said Hathaway, as the plant towered over us. The nightmare is if she breeds. A single stem of Japanese knotweed can produce 190,000 flowers. As we talked on the hillside, tiny white seeds pattered onto my notebook and covered my hair. “If it suddenly decided to mutate and each of these grew into new knotweed,” said Hathaway, “then we’ve had it, I’m afraid.”

When we emerged from the vegetation, a couple was arguing by the side of the road. The weed loomed over the fence behind them. Hathaway took me on a tour of vantage points across the city, from which we could look out and see itadori lying over Swansea hillsides and abandoned plots in great, regular washes, like a green avalanche come to rest. We finished in a graveyard that had been treated with herbicide four or five years earlier but that, because of a lack of donations or a viable church congregation, was rapidly being overwhelmed again. “The scene you expect to come across is a skull on the end of a stem,” Hathaway said as we tripped over the uneven ground. It was the only moment all day when his cheery demeanor — the necessary optimism of a man who finds himself swimming an ocean — deserted him. The swallowed gravestones around us looked completely peaceful, and completely wrong. “You don’t get used to it,” he said. We drove back to his office, and he left me by my car.

Siebold’s first contact with the Japanese was with a group of shipwrecked sailors that his vessel, De Drie Gezusters, brought aboard after a typhoon in the East China Sea. “Their competence and refined behavior,” he wrote, “was most astonishing.” Siebold was twenty-seven years old. He was on his way to the Dutch trading post of Deshima, a man-made island in the harbor of Nagasaki, where he was due to serve as the colony’s doctor. For almost two centuries, thanks to its apparent lack of interest in converting Japan to Christianity, the Netherlands had been the only European nation allowed to maintain any kind of presence in the country. By 1823, Deshima had become a drab, claustrophobic place. Two ships visited each year. Access to the mainland was possible only by crossing a guarded bridge. Still, the Japanese were fascinated by Western scientific knowledge, which they called rangaku (“Dutch learning”), and European medical men sent to Deshima were expected to trade on this curiosity and bring back as much information about Japan as they could. (David Mitchell’s novel The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet investigates this period; its protagonist is a Dutch clerk posted to Deshima.) Siebold was the son of a distinguished family of German doctors and recognized in himself the ability to do great things. “I do not intend to leave Japan until I have described it in detail, and until I have collected enough material for a Japanese museum and a flora,” he wrote to his uncle.

For five years, Siebold responded to the shogun’s intricate restrictions on the activities of foreigners by ignoring them. He learned to read and write Japanese, which was against the law. He performed cataract operations, fixed cleft lips, and removed tumors, and because of his fame he was allowed to open a medical school in Nagasaki, where his students paid him in essays about Japanese life and brought him plants, animals, and models of bridges. He employed an artist, Kawahara Keiga, to paint more than a thousand pictures of plants and of daily life. And he fell in love.

Otaki was the sixteen-year-old daughter of one of Seibold’s patients. He brought her to live with him on Deshima (she was designated a concubine, the only status a woman was allowed on the island), and they had a baby. All the while, he continued his relentless, illicit learning. When he went for a walk, Siebold carried a hollow cane, which he used to collect seeds secretly. In 1826, on a long trip to Edo to see the shogun, Siebold hid a compass in his hat and drove his minders crazy by disappearing up hillsides to meet with local geographers. Villagers presented him with gifts: an albino deer, two salamanders. In Edo, he persuaded the court astronomer, Sakuzaemon, to give him a rare map, and the physician, Genseki, to give him a linen cloak embossed with the imperial insignia. On the way back, he used a sextant to measure the height of Mount Fuji, which was a state secret.

Siebold’s luck gave out on September 18, 1828. As he prepared to sail for Europe with eighty-nine crates of animals, plants, and objects, a storm forced his ship aground. The authorities moved in and the doctor stayed up all night copying out maps and hiding precious items in false-bottomed flower boxes. The ship was allowed to sail, but Siebold was not: he was detained and interrogated for nine months. Sakuzaemon, the astronomer, was questioned, had his teeth smashed in, and died. His son and around fifty other Japanese, many of whom who were only loosely connected with Siebold’s activities, were exiled to remote islands or imprisoned. Toward the end of 1829, Siebold was banished from Japan for life. On the morning that he sailed for Europe, a small boat carrying Otaki and their two-year-old daughter, Oine, came out from the shore, and Siebold waved goodbye to them in the mist.

He landed in Antwerp the following July. The Belgian war of independence began the following month. It took Siebold more than two years to find his feet, track down his scattered collections, and rent a large house on a canal in Leiden. He opened a nursery in the poorer end of town and began to market his unearthly sieboldianas across Europe: hostas, wisterias, a blue hydrangea that he named for Otaki.

Invasive species often inspire wonder, at first. After observing fleas in the early nineteenth century, the people of Aitutaki, one of the Cook Islands in the South Pacific, concluded from their restless nature that they must be the souls of dead white men. In 1833, as Siebold was publishing the first installment of his encyclopedic study of Japan, Charles Darwin marveled at the success of the artichoke thistle, a native of the Mediterranean, on the plains outside Buenos Aires. “Over the undulating plains, where these great beds occur, nothing else can now live,” he noted. Darwin theorized about the catalogue of effects — on invaders and invaded alike — that must have followed the disembarkation of the first colonists in the New World. He pictured European pets and farm animals, unchecked by enemies and masters, running amok in the vastness. “The common cat, altered into a large and fierce animal, inhabits rocky hills.”

In 1847, the Japanese knotweed won a gold medal from the Society of Agriculture and Horticulture in Utrecht for being the most interesting new ornamental plant of the year. It was another century before biologists began to realize that a systemic collision was taking place: humanity’s project to connect the world was overriding the earth’s natural barriers of water, mountain, and desert. During World War II, globalized supply chains introduced 140 alien species of grass into the forests of Finland. In the early Fifties, the brown tree snake, a native of Australia, arrived in Guam, where it has wiped out twelve bird species and reached a population density of 13,000 snakes per square mile.

Biologists sometimes use the term “enemy-release hypothesis” to describe the ability of foreign creatures to overwhelm a new habitat. If there is a food supply and nothing trying to eat you, then even humble beings can become monsters. In the case of itadori, her roots found new vigor in the tarmacked towns and polluted waterways of industrial Europe. The two hundred or so insects that plagued her in Japan and the stronger rivals that stole her light were nowhere to be seen.

In the 1970s, a plant biologist named Ann Conolly published the first maps showing the spread of the knotweed across the U.K. In 1981, itadori became one of the first plants named under Britain’s Wildlife and Countryside Act, which makes it a criminal offense to release the weed into the wild. But like many other well-meaning pieces of paper intended to stop invasions, the law against the knotweed didn’t change a damned thing.

Within a few years of planting itadori, Victorian gardeners became alert to her unbounded ways. They loved her — she was “handsome in rough places,” according to William Robinson’s The English Flower Garden — but they could not stop her. In 1887, just a year after her escape was noted in Maesteg, the fellows of the Microscopical Society in Oldham, 200 miles to the north, found that knotweed “turns up unexpectedly in nearly every piece of cultivated ground” in the town’s park. Twelve years later, Gertrude Jekyll, a powerful figure in Britain’s Wild Garden movement, was urging caution to her readers. Still, the plant was sold as a fashionable Japanese import until the 1930s.

In the United States, where itadori had been planted in Central Park and had become a staple shrub of large gardens and woodland walks, the mood began to turn at about the same time. In 1938, for example, the Massachusetts Horticultural Society was publishing advice on “Exterminating the Knotweed” alongside tips on “Burning Weeds with a Torch” and “Burning Out Tree Stumps.” The U.S. Forest Service observed that knotweed clusters can wait for fifty years before their growth turns suddenly exponential. In 1999, a single clump of knotweed washed down the Hoh River in Washington State during a winter flood. Within five years, it had grown 18,585 canes. The plant is present in at least thirty-six states, and is considered “noxious” in seven of them. It is occasionally compared to kudzu, its infamous Japanese relative, whose spread across the American South became so overwhelming in the 1940s that it was believed, for a time, to be the work of Japanese spies.

The only reliable method for killing knotweed is poison. You can use ordinary old glyphosate, also known as Roundup, the systemic herbicide developed by Monsanto in the 1960s. But what you really need is patience. It takes five years of repeated applications, in the spring and in the late summer, for the chemicals to go through the plant and kill the rhizomes. There are two ways to go about it: spray the leaves and canes, or inject the poison into the stems. Stem injection is better for targeted work, gives a higher dose to each cane, and sounds more efficacious. In truth, the two methods work equally well — or poorly. In the U.K., the only other technique, which is rarely used, is to dig out a plant completely. This means excavating to a depth of two meters and a radius of seven meters, and carting the resulting 308 cubic meters of earth to a specially designated landfill. The remaining soil must be lined with a copper membrane. This operation costs as much as £54,000 (nearly $80,000) per square meter of knotweed.

It helps to love what you do. When I went to see Brian Taylor, a professional knotweed killer based in Northamptonshire, he excused himself to fetch a book. He promised that it would be the oldest book on plant spraying I would ever see, and returned a few minutes later with Ernest Lodeman’s The Spraying of Plants: A Succinct Account of the History, Principles and Practice of the Application of Liquids and Powders to Plants for the Purpose of Destroying Insects and Fungi (1896). We sat quietly at his kitchen table while Taylor, a large man with curly black hair, leafed through early photographs of men in sou’westers treating orchards, and diagrams of steam-powered spraying machines. “I am so into this you wouldn’t believe,” he said.

Taylor, whose father was also a weed guy, spent his teenage summers helping out on pesticide experiments at a government research station in Oxfordshire. In his early thirties, he spent four years testing the nozzles of crop sprayers in a large wind tunnel before getting into the knotweed game full-time. Now in the prime of life, drinking a cup of tea, Taylor exuded the fulfillment of a man confronting his nemesis at last. “Japanese knotweed is, without doubt, the supreme weed,” he said. “People used to say that if humans disappeared in the U.K., we would be replaced by an oak forest in a few hundred years. That is no longer the case. The future would be Japanese knotweed.”

The plant’s implacability provokes this kind of apocalyptic thinking, along with visions of the financial and political power that would be required to get rid of it by force. The last cost estimate for a nationwide spraying program in the U.K., made ten years ago, was £1.56 billion. Taylor briefly sketched his own war plan for me, which depended on emergency legislation that would allow access to all private property to destroy those volcano-proof rhizomes. “I don’t think the army could do it,” he said. “You would need special acts of Parliament. If you were serious about it, you might get control in twenty to thirty years.”

In the real world, poisoning the weed means skirmishing, and protecting what we have. It was a summer afternoon and we went into Taylor’s vegetable garden. We were surrounded by well-kept fences and the neat backs of suburban houses. Taylor rotated through the four points of the compass, calling out the location of the nearest knotweed in each direction: “Thirty meters that way. Fifty meters that way. A hundred meters that way.” He turned to me. “It’s scary, isn’t it?”

The job that afternoon was a stand in the village of Claybrooke Parva, across the border in Leicestershire. It was on a patch of common pastureland. The local church had hired Taylor to kill its knotweed with stem injection. As we drove, Taylor took calls for other jobs and we talked about the history of the weed. It struck me that men driving around the countryside in poison-filled vans a century and a half after the alien landed represented, in a way, our island’s evolutionary response. “We are the predator, if you like,” said Taylor. “The knotweed destroyer.”

The weed was in a meadow, bookended by a hawthorn tree and a spruce, and it stood with the authority of a small forest. Taylor put on a set of blue overalls, took his JK1000 stem-injection gun out of its padded case, attached a tub of Roundup Pro Biactive, and crawled into the canes. Leaves shook. From the outside, it looked like a large but benign animal was loose in the undergrowth. I got on my knees and followed Taylor in. Under the leaves, it was cool and dry and clean. The light was filtered green. Beyond the weed, we could hear the small, contented sounds of village life: the jingle of car keys, the start of a lawnmower. “It makes me think of my childhood, building dens,” said Taylor. He inserted the gun’s hollow needle into one of the stems and pulled the trigger to release the herbicide. As he worked, the afternoon filled with the discordant sound of church bells. Taylor handed me the gun, and I started to pierce the knotweed stems just below their joints. Sometimes the poison overflowed and ran down the outside of the canes, making them sticky. The bells rang out. Taylor watched gravely. “This is not doing the lady any good at all.”

Three months later, he would send me a photograph of the site, which showed a bare and shriveled mass. But that afternoon, as we headed home, Taylor told me that he often pondered the philosophical soundness of the concept of weeds. In Japan, itadori is just another volcanic bush. It contains resveratrol, a polyphenol compound that is believed to counteract heart disease and the effects of aging. Taylor kept talking about the knotweed’s power and versatility, and I thought I detected in his voice some of the admiration that I had heard from other professionals who had dedicated their working lives to controlling the weed, a feeling that Trevor Renals, the national invasive-species adviser at the U.K.’s Environment Agency, described when he told me about the time he saw a shoot of knotweed rise from a plant that he thought he had killed thirteen years earlier. “That’s my girl.”

But in fact what Taylor was expressing was not admiration but the pain of recognition, another feeling that many people experience when encountering the plant, and one that I found myself suffering from during the summer I spent in its company. There is no weedier or more invasive species than humankind, and the world that we have made is for generalist organisms like us — Norwegian rats, common crows, zebra mussels, long-horned beetles, brown tree snakes — that can thrive on the far side of any mountain. “I mean, Antarctica is the only place we’ve not actually gone to and adapted to,” said Taylor. “Japanese knotweed is the same.”

There is a photographer in Osaka named Koichi Watanabe who has spent much of the past decade traveling around the world and documenting the spread of knotweed, which he regards as both a consequence and a metaphor of our own globalized and increasingly homogeneous existence. One morning I spent an hour with him on Skype. In 2006, Watanabe told me, he photographed a knotweed infestation in Katowice, in Poland, in the lee of two huge water towers. Five years later, he returned to find the towers demolished and the weed abundant. “This indicates the future scene,” he said. “If human beings are gone from this world, itadori remains.”

Toward the end of The Day of the Triffids (1951), by John Wyndham, the book’s narrator, a biologist named Bill Masen, sits in his fortified garden and considers whether to move his family off Great Britain. The island has been almost completely overtaken by lumbering plants that can communicate with one another and kill people with lashes of their deadly stings. Masen has been asked to join a colony of fellow survivors on the Isle of Wight, where he might have the space and time to devise a drastic weapon against the plants. “I could see hundreds of them in a dark green hedge beyond the fence. There must be research — some natural enemy, some poison, a debalancer of some kind, something must be found to deal with them.”

The Bill Masen of the war against knotweed is a entomologist named Dick Shaw. In Swansea, Sean Hathaway told me that he could see no end of the conflict “until Dick becomes our savior.” Since 1994, Shaw has been dreaming of releasing a natural knotweed enemy — what scientists call a biological control agent — to stop, and turn back, the advancing canes. He works at the Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International (CABI), a little-known intergovernmental research organization that used to be named the Imperial Bureau of Entomology. For more than three hundred years, the British Empire served as the planet’s most prolific vector of alien plants and animals, and the bureau was set up in the early twentieth century to protect crops in distant lands. Now CABI’s U.K. research center, in a stately home in Egham, on the outskirts of southwest London, does a lot of work unpicking natural invasions. It acts as a kind of international clearinghouse of pathogens, disease, and infestations.

On the afternoon I visited, Shaw, a direct, positive man in his forties, took me through a row of small greenhouses in an old stable block, all of which are growing plants that have turned invasive somewhere in the world. There was wild ginger, a menace in Hawaii; Himalayan balsam, running riot along Europe’s rivers; and Australian swamp stonecrop, a pest in Belgian canals. Signs on the doors hinted at the experiments under way. predator mite applied. last for six weeks. When we reached the final greenhouse, Shaw opened a back door and lifted the lid off a freezer box containing Azolla filiculoides, the floating water fern, a South American pond plant for which his team had found a highly destructive weevil. If afflicted pond-owners get in touch, Shaw sends them weevils in the mail.

Identifying a suitable biological control agent requires years of repetitive testing, against dozens of native species, to ensure specificity. Even then, there is no guarantee that an agent will ever be released. In one greenhouse, Lantana camara was growing. Lantana is a South American shrub that is causing devastation in the Galápagos Islands. CABI has found a rust fungus, generally the most specialized of all biocontrol agents, that will kill it. “A rust is your dream,” said Shaw. But so far the Ecuadoran government has chosen to spend its invasive-species budget elsewhere. “We bid for it. We wanted a hundred grand or something,” said Shaw. “They spent it all shooting goats from helicopters. Every penny of it.”

Shaw could see the potential of using a natural enemy against Japanese knotweed as soon as he started working on the problem, in the mid-Nineties. He had returned to arthropods after a few years working for Goldman Sachs and a few years working as a builder. “It was a sitting duck from the outset. We knew there were loads of potential enemies in Japan; we knew it was exotic to the country; we knew it was pretty much clonal,” he said. “And everyone hates it.”

Shaw made his first trip to Japan, in 2000, with John Bailey, a professor at the University of Leicester, who had used DNA analysis and chromosome counting to successfully trace Siebold’s plant back to Nagasaki. Then Shaw began the process of auditioning 186 potential Japanese predators. As we talked in the sunshine, he occasionally turned nostalgic when he recalled the hopes that he had entertained for each. “There was a weevil, two beetles, a sawfly,” he said. “Really nice sawfly. Really damaging. Two leps. Lepidoptera.” There was also a rust fungus, which turned out to feed on another plant during the winter, and some spectacular Hepialidae moths, which Shaw brought back with him on the plane from Japan. “I had these plastic boxes. It was literally chewing out of them in my suitcase.” He shook his head. “It chews out of boxes. Amazing beast.”

After five years, there was only one candidate left. Shaw led me into a gloomy garagelike space lined with sinks, yellow plastic buckets, and bottles of glyphosate. I saw a biohazard sign and a large steel autoclave. On the left was a white door marked growth room 1: psyllid culture. As we went in, Shaw told me that he would have to search me thoroughly before I left the premises. That is because, five years after it was approved by the British government, the Aphalara itadori, a jumping plant louse named for the knotweed in its native country, is still allowed only at eight secret testing sites around the U.K. Inside the small room, hundreds of tiny, speckled brown bodies were stuck to pieces of yellow flypaper under the lights. Along a wall, in a row of plastic cases filled with young knotweed plants, the rest of the psyllids were feasting.

For someone accustomed to seeing the weed pristine, it was a shock to see it in the presence of death. A. itadori feeds on itadori sap. The psyllid nymphs suck the leaves dry, leaving a smoky white trail, before going to work on the stems. I walked along the wall, looking at preyed-upon knotweed that was sprouting dwarfish leaves in an attempt to outgrow the pests; their edges were turning black and about to die. Shaw said that one of the main challenges in the growth room was how quickly itadori was devoured. At the test sites, however, it has been a more complicated story. Shaw has released 300,000 lice, but the research has been interrupted by poor weather and the constraints of CABI’s license. Sometimes he dreams of driving down a motorway, psyllids pouring from his car windows.

Nonscientists are often skeptical about the release of one alien species to hunt another. They only remember the farces: the kiskadee in Bermuda, the cane toad in Australia, the old lady who swallowed a bird to catch the spider to catch the fly. In fact, there are almost 7,000 biological control agents currently deployed around the world to contain invasions, and we rarely notice them. They take time. If everything goes well in the U.K., it will be twenty or thirty years before the Aphalara really makes an impact, and even then the flies will never eliminate the weed. Shaw spoke instead of “a slow opening of the canopy.” Soils and their fungal populations will rebound. The natives will rise, and itadori — naturalized, in a manner of speaking, by the company of her pest — will become just another bully of the undergrowth, a bramble or a bracken. In the process, by the measure of one more added species, the islands of Britain will take one step closer to ecological conformity with the islands of Japan.

“I could sum up the future in one word,” J. G. Ballard said in 1994, “and that word is boring. The future is going to be boring.” I got the sense that Shaw, a scientist steeped in the devastation of the Homogenocene era, would take boring. Several years ago, he told me, he had given a lecture in Mauritius about Varronia curassavica, an invasive shrub that was reduced to unremarkable proportions by insects imported from Trinidad in the 1970s. No one had any idea what he was talking about. “That would be a perfect scenario,” he said, “if everyone forgot what knotweed was by the time my child grows up.”

In large ways and small, Siebold’s personal project to end the isolation of Japan proved unstoppable. The breach was made. In 1844, he persuaded King Willem II of the Netherlands to let him draft a letter to the shogun, Ieyoshi, on the king’s behalf, describing the reality of a shrinking world. “An irresistible force draws nations to each other. Due to the invention of steamships, the distances are constantly diminishing,” Siebold wrote, as the king. “Any people wanting to exclude itself from such general rapprochement will have to face the hostility of many.”

In 1859, at the age of sixty-three, Siebold finally got his chance to return to Japan. This time, though, he went as a participant in the frantic diplomatic efforts that accompanied the opening of the country under pressure from British and American warships. By then, he had changed his opinion about the promise of international rapprochement. “In my mind I drift back to the Japanese island kingdom, for the country where I spent my scholarly youth,” Siebold wrote to a friend, “and which is now threatened by a European culture with all its horror and misery.” He carried a small lacquer box with portraits of Otaki and Oine for the rest of his life.

On a perfect sunlit morning, toward the end of the knotweed-killing season, I took the train to Leiden. In the botanical garden, where fifteen of Siebold’s original plants are still growing, I met Carla Teune, its retired curator. Teune told me that the Netherlands was the world’s largest producer of seedling potatoes, which came originally from Peru. “As soon as people think they are profitable, they carry,” she said. “You feel a bit sad, but it is also inevitable.”

I walked out along shining canals to find Siebold’s nursery. In the years after his death, in 1866, the garden, which had once boasted more than a thousand species, went untended. By 1883, it was overrun with knotweed. Later, the land was turned over to rows of two-story housing. The only traces of the nursery were street names — Sieboldstraat, Floresstraat, Decimastraat — and a few petals formed in bricks in the road. i love flowers, and flowers love me read a sign, in English, in someone’s window. I nosed through a small park, looking for knotweed, and went into the local bar, Café Decima, to try to talk about Siebold and Japan. A few guys playing cards told me I was in the wrong place. They said the street names were the result of Asian immigration to Leiden.

That evening I walked until I found itadori. The weed was penned into a railway embankment near a strip of chain hotels and a contact-lens factory. The canes seemed eager and waiting for something, like a crowd of sports fans hanging over a fence. I went and ate all-you-can-eat Japanese and the next morning I woke up early, to be at the museum in Siebold’s old house when it opened. Low-lit cabinets were filled with some of the 25,000 fragments of Japan that he brought back: kimonos, dictionaries, a stuffed heron, his dog Sakura, the fragile remains of archived plants. Upstairs, in a set of shallow drawers, I found a copy of the secret map that led to his expulsion. Behind me, a television on the wall played an interview with one of Siebold’s surviving German relatives, Count Constantin von Brandenstein-Zeppelin. The count, a great-grandson of the airship builder, wore a brown tweed suit and brandished Siebold’s hollow cane. “This was forbidden,” he was saying. “But I believe that the Japanese and all persons connected were happy he took this pragmatic path.”

A few days later, I reached the count on the phone. He is the custodian of Siebold’s lacquer boxes. “I think his point was: humans have to exchange,” he told me. “Humans with their brains and their knowledge and their science, they have to do exchange, and to surpass the constraints of nature on one side and the people who don’t understand it on the other side.” The count lives in a castle in a forest not far from Frankfurt. In Germany, itadori is called Japanischer Staudenknöterich, and I asked him if there was any in his garden. “Ja,” he said, and he started to laugh. “It is growing so horribly fast.”