In the old days, when a new movie arrived at the theater, it was a collection of heavy, cumbersome cans containing the reels of 35-millimeter film. That physicality has nearly vanished. Today, a movie consists of a so-called Digital Cinema Package and looks like a plump DVD. It’s inserted into a player at the theater, and the distribution company transmits an electronic key that frees the film for screening.

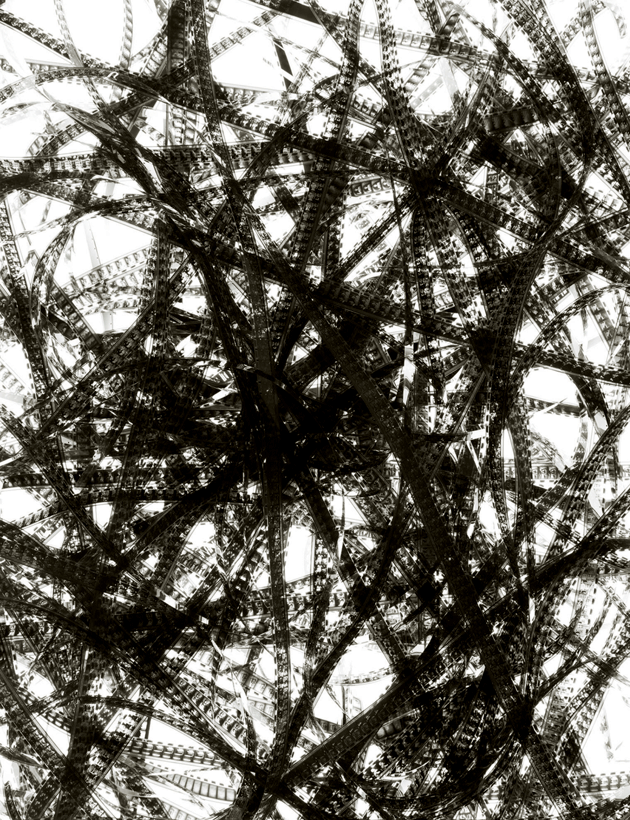

On a film set, of course, the director of photography still frames an image and adjusts exposure and focus. But there are no silver salts on celluloid, waiting to be burned into. When the film is edited, there are no reels to examine by eye and cut by hand. I don’t mean to sound wistful, and I realize how much money these advances save, but few now hold film stock between their fingers or think of it as something alive, the material of story. A bond with reality has gone, and sometimes you wonder whether that fosters our feeling that movies are a fleeting art.

In a similar sense, when movies are virtual rather than physical, they become unstable. Near the end of 2014 we had a hysterical interlude with Sony and The Interview. It went from finished movie to terminated entertainment within just a few days. Then it was back as a liberated thing, ready for our fun. Many who saw the film almost wished that it were still banned — that certainly would have enhanced its legend. Imagine a scholarly conference, decades hence, at which Seth Rogen and James Franco could rhapsodize over the chimerical Interview as if it were Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons.

Now, that was a physical movie once, a story in cans, and a glorious one, but disliked by its owners. The Magnificent Ambersons was released in 1942 by RKO, and it does exist, at eighty-eight minutes. You can get it on DVD; you can sometimes find it playing on a big screen. But the Ambersons that Welles wanted to make was more than 130 minutes. Though the film we have is ravishing, the full version might have eclipsed Citizen Kane. Some sources suggest that the excised footage was dumped in the Pacific Ocean along with deleted material from many other films.

That which is lost is especially desirable. So people have been searching in the abiding hope that there might still be a print of the entire film, in a cellar or an attic or a Rio de Janeiro favela. And perhaps there is — I’ll get to that in a moment. But first, let’s consider the curious nature of lost or out-of-reach films and what makes them so precious.

You can only watch one picture at a time,” my mother would tell me. “Be patient.”

She was right, but I was never satisfied. It was 1950, and we had walked up to the Regal or the Astoria in our South London suburb to see something. Let’s say it was Burt Lancaster in The Flame and the Arrow, and my mother was trying to be as eager as I was. But here came the trailer for Richard Widmark in Night and the City! “Look, it’s London,” said Mum, as Widmark ran through bomb sites in the dark. I was nine, old enough to absorb the excess of the ad lines slashing the screen. The anticipation of Lancaster’s grin (two minutes away) yielded to Widmark’s craven sneer, and I wanted it to be next week already. “You said the same thing last week,” she reminded me. That’s when the trailer for The Flame and the Arrow had seemed more vital than Jimmy Stewart in Winchester ’73.

The dynamic of moviegoing was clear: you could see only one picture at a time, no matter how tantalizing you found the coming attractions. I knew the pattern of distribution. A film opened in the West End of London, then seeped out to the suburbs: first the north and then the gray infinity of the south. We had the picture for a week. And then it was gone. I can still remember missing Alan Ladd in Branded (it may have come during that holiday on the Isle of Wight). Kids teased me rotten over that hole in my life. They said it was likely the best film ever made.

When I discovered Red River, it was rapture to sit there on its bank and watch. The film was a river as much as a story, and forced you to stay with it. With a book, you could pause before the denouement and have a nap. The book would wait patiently. The music you liked was on a record; you could go back and revisit its immediacy until you knew it by heart. But a movie was wild and it went away — which meant that old movies were like stale newspapers. For a few hours, watching them was as urgent as knowing the score in today’s Chelsea–Arsenal game. But the teams would play again soon. Who wanted to see old news? Who bothered to be sure the old stuff was safe in some vault?

We hear it said that at least 70 percent of the silent movies made in this country have been lost, as well as a frightening proportion of the sound films. These assertions are undoubtedly correct, just as everyone who fought in the First World War is now dead. It was bound to happen: if the machine guns and influenza didn’t get you, old age was waiting. So we should be more understanding of the reckless commerce and cultural indifference that lie behind these losses. The companies that owned motion pictures lacked the space to store them; they never grasped that there could be a second commercial life for their product, never anticipated the arrival of television, which might have been obliged to show live executions and traffic accidents if it were not for old movies. Also, they knew the films were decaying anyway. The images themselves tended to fade and disappear, and the base on which the film was printed was made of cellulose nitrate, a volatile compound capable of turning to dust or to an oozing putrescence that gave off a foul odor before exploding or catching on fire.

In 1987, I visited the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas. The Ransom Center has one of the world’s great gatherings of literary manuscripts. But it has other holdings as well, including the archive of David O. Selznick, the movie producer. I was in Austin with Jeffrey Selznick, one of his sons, with whom I was making a documentary to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Gone With the Wind. The hope was that we would find some useful materials: screen tests for Wind, or 16-millimeter home movies of the era.

The helpful staff at the Ransom Center took us to where the film was stored, and as we came out of the elevator, Jeffrey and I knew we were on the right floor. You could smell the nitrate several hundred feet away, and that meant it was dangerous. An explosion in that building would have put D. H. Lawrence, Graham Greene, James Joyce, and a Gutenberg Bible in jeopardy. Within forty-eight hours, the film was moved to an abandoned missile silo on the edge of town.

Not that anyone is going to save actual film stock from time’s erosion. What happens now, when an archive has sufficient funds, is that a film on nitrate is transferred to a more stable base. Then the film is stored at the optimal temperature and humidity — and you wait for time to take its course. The colors in nearly every system except for the original Technicolor have deteriorated in the past eighty years. No one knows whether the digital versions of movies that are now ubiquitous will be safe and eternal. It also remains an open question whether original prints of the alleged golden age will stand up to time better than the paintings of Vermeer and Velázquez — or seem as beautiful. (Those canvases, too, are subject to physical decay, but Las Meninas is unlikely to incinerate the Prado.)

Scholars and librarians ask why the country most associated with the development of cinema does not lodge a copy of every film with the Library of Congress. In fact, Congress provided for this very practice more than a century ago, in the Copyright Act of 1909 and its subsequent amendments. But then the library itself declined to follow through. I think this reflected some anxiety over where to put the film, and how long it would last. Ultimately the LOC settled on a selective process, under which they have tried to fill the gaps created by their own policy of not enforcing the original act.

Even if the Library of Congress had been as thorough with films as it was with written materials, another problem would remain. The Copyright Act applied to copyright holders, meaning the companies that financed movies and released them. So when Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released Greed, in 1924, the company would have simply deposited the version that played in theaters. Yet Greed, like many films, emerged from extremely muddled circumstances. It may be our most celebrated lost film, its title an apt reflection of the attitude of the industry that created it. But Greed is not simply lost.

Erich Stroheim (to use his given name) was a humble Viennese who came to America early in the twentieth century and rose to some prominence as an actor playing Germanic figures in Great War movies while advising studios on uniforms and military etiquette. As Erich von Stroheim, he began to direct, and his films — Foolish Wives, Blind Husbands — revealed an unusual grasp of psychological realism, then in its movie infancy. He was also someone who challenged bosses.

In the early 1920s, he signed on with the Goldwyn Company to make a movie from Frank Norris’s novel McTeague. Stroheim’s contract for what became Greed stipulated that the film would be about a hundred minutes long and that it would cost $175,000 (though Goldwyn doubled the budget shortly before shooting began). Stroheim wanted real locations — he took the crew to Death Valley in 120-degree heat. He also shot far more than he had promised, and his first cut ran forty-two reels, or about ten hours.

Lucky to have shot it his way at all, Stroheim knew enough to attempt a second cut, and proposed showing this six-hour version in two parts on successive nights. His luck didn’t hold: the project fell under the aegis of an old enemy, Irving Thalberg, when the Goldwyn Company became part of MGM.

One person who saw the ten-hour version was Irene Mayer, the daughter of Louis B. Mayer. She said it was stunning but boring; it had immense and great things, but too many of them. Her father and Thalberg obligingly ordered the film cut down to two hours. The director couldn’t bring himself to watch the released version until ten years later. “It was like seeing the corpse in a graveyard,” he noted. “I found a thin part of the backbone and a little bone of the shoulder.”

Greed is what Stroheim is now best known for, along with his mournful onscreen presence in Renoir’s La Grande Illusion and Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard. It is treasured by film lovers, recognized as one of the greatest of silent pictures. You can still marvel at Stroheim’s vision of Death Valley as the ultimate golden hell, and his keen eye for the way money supplants sexuality in the heroine’s dreams.

The MGM-sanctioned version of Greed has been available for decades, at 140 minutes, and leaves no doubt about Stroheim’s genius, his powerful realism, and his antagonism toward Hollywood’s money-grubbing instincts. There is also a scholarly version, fleshed out to 239 minutes with surviving stills and accounts of what is missing, which was assembled by Rick Schmidlin for Turner Classic Movies. MGM got rid of most of the cut material, though, and no amount of searching has ever brought it to light.

Of course, we can’t know what we haven’t seen. We do know that we are missing films such as the 1926 Great Gatsby, as well as pictures by Mauritz Stiller and Yasujiro Ozu, to name a few. In addition, thousands of films have been released as something less than, or other than, what their makers intended.

We have fragments from Stonehenge and Mesa Verde, and we hardly know their purpose or history. Robert Musil published the initial volumes of The Man Without Qualities, but the long final section was cobbled together by his widow. Similarly, Charles Ives’s Fourth Symphony is played in a compromise between the composer’s dream and the practicality of performance. If Stroheim was the genius, fatalist, and self-destructive figure we cherish, did he expect the full version of Greed to keep his name alive, or the ruined remains to become his Ozymandian monument?

Sometimes being lost can help. In 1958, Alfred Hitchcock made a mystery film that some people thought gave away its ending too early. It also lacked the sardonic edge that people relished in his work. Vertigo was gloomy, oppressive, and hard to enjoy — and it did poorly at the box office. This may have stung Hitchcock all the more because it was as close to a confessional as he would ever come.

Almost immediately after Vertigo, however, Hitchcock’s status improved. Psycho, released a couple of years later, was a success that saw art bleed into box office, and any question about Hitchcock as a mastermind was set aside with the 1967 publication of François Truffaut’s book-length interview — a landmark in conveying what a film director might be. Then Hitchcock proved himself a brilliant showman by withdrawing a select group of his films from circulation. (It was another mark of his intelligence that he controlled the rights to these pictures.) The group included Vertigo, and the withdrawal started in 1973, just as the discipline of film studies was invading colleges and universities.

Interest in the “lost” film soared. A few, who had loved Vertigo in 1958, could dine out just by recounting its tortured plot — it is the story of a lost woman. Occasionally there were reports of secret screenings. The film was written about with visionary adoration. Hitchcock died in 1980 — and three years later, when the film was rereleased, it took off. The Sight & Sound poll of 1982 placed it at number seven (out of nowhere); by 2002 it was second only to Citizen Kane; and in 2012 it was, officially, “the greatest film of all time.”

In none of this consideration do I ask how good Vertigo is. What intrigues me is how its deferred glory seems just a larger version of my longing for Branded. If Orson Welles had lived beyond 1985, and if he had owned Kane (instead of just having a contract that kept it uncut and stopped Ted Turner from colorizing it), his audacious coup in 2012 could have been to withdraw the film. Its victory in the 2022 poll would then have become a foregone conclusion.

Which brings us back to The Magnificent Ambersons. Welles finished editing the film in early February 1942, producing a 131-minute cut with his voice-over narration. The last of this work was done in Miami, with his editor Robert Wise, just before Welles flew to Rio de Janeiro, where he had plans (rather vague) to make a film for the war effort — something that would improve relations between the United States and Latin America. Welles and Wise foresaw further refinements to their cut, and a print was sent to Welles’s hotel in Rio so that he could study it as he prepared to shoot Carnival footage and meet the dancers at that nonstop festival.

Welles was fond of dancers. He plunged into Carnival and neglected the possibility that back in Los Angeles there might be doubts brewing about Ambersons — it was, after all, long, depressing, and darker than the Booth Tarkington novel that was its source. Furthermore, Welles had split the RKO administration between those who believed in him and those who thought he was all hot air. He had also been forced to accept an amendment to the Kane contract that canceled his right to a final cut. He should have foreseen that some of his studio enemies might gang up on Ambersons, and he owed it to his film to return to Los Angeles at the first sign of trouble.

Instead, he stayed in Rio, and in his absence the film was chopped down and given a fatuous happy ending. This interference seems to have broken Welles’s heart. He returned to America in due course, but without the unique print of his cut that Wise had sent him. He could have kept it and given it to a library. Who would have refused it? But he left open the possibility that somewhere in Rio, or in wider South America, there is that nitrate print, coiled among the snakes, the heart of darkness and greatness.

Perhaps Welles believed that fate would preserve his picture. Or was he sufficiently melancholy to see that after you’ve made the perfect film, you lose interest in perfection? He had already made the complete Hollywood movie, one that was studio-bound, lovingly fabricated, traditional and innovative at the same time — and done on a carte blanche contract, as if he were the most venerable of artists and not just a shocking kid. No wonder much of Hollywood hated him. No wonder loss and downfall became his subjects. Remember that Citizen Kane is a song for the emotive power of vanished things — although Kane owns that famous sled, along with everything else in his warehouses, he has lost track of it as anything but a memory.

Not long before he died, Welles said, “I believe that the movies — I’ll say a terrible thing — have never gone beyond Kane. That doesn’t mean that there haven’t been good movies, or great movies. But everything has been done now in movies, to the point of fatigue.”

Is that remark terrible because it exposes his vanity, or because it might be accurate? Was there a fatalist in Welles, a rueful magician, who realized that triumph ends in smoke? Perhaps there was even a moment in Stroheim’s struggle when he said, “Very well, I will make an impossible movie. And then I will lose it.”

Some devotees of Welles and Stroheim will be upset by such speculation, because they prefer to regard their heroes as victims of a cruel system. But the point goes beyond these two cases. The culture of film has changed so much. Technology has carried us forward and turned film history into an easily accessible archive that awaits on your shelves or your device of choice. But do those old movies survive repetition? Or were most of them like fruit, sweet for a few days but perishable?

Welles said he had seen so much Kane in editing it that he could not endure to watch it again. Suppose Casablanca, which Turner Classic Movies has already aired 130 times, were lost, except for some emblematic stills and a snatch of “As Time Goes By.” Think of The Philadelphia Story as no more than a recollection by an aging Katharine Hepburn, in which she muses about the warehouse fire that consumed it. “Oh, that picture was yar,” she says, leaning on a few fragmentary memories.

Memories and fragments are the nerve system of movies. All the work can come down to one line or a single glance — like that huge mouth saying “Rosebud.” During his last fifteen years, Welles was making a feature film, The Other Side of the Wind, about a movie director, played by John Huston. When Welles died, the shooting was close to complete, but the ownership of the film was as dismayingly confused as most of his affairs. In the three decades since, there have been several attempts to resolve rights and to finish the film as Welles would have wanted. It has become another legend, by virtue of being lost.

But now we may be closer than ever before. The labyrinthine legal issues are said to be resolved. The picture needs to be cut and finished. There was a dream of opening it at the Cannes Film Festival this May — Welles would have been a hundred on May 6, 2015. Still, as of April, there was no editor on the project, substantial funds were required for postproduction work, and no one had yet agreed to release the picture.

How good could the film be? The script is very long; the fragments shown so far do not cohere; most of the actors are gone, so reshoots are impossible. More than ten years ago, I saw a couple of passages, completely out of context. One was a sex scene, more candid and arousing than anything else Welles ever put on film. It was striking, but it didn’t seem to be from a Welles movie.

Welles did leave some instructions behind, but he also said the subject might be dated and that he had thought of turning it into an “essay film.” Yet our anticipation demands something complete and impressive. Or could this great rumor remain unreleased — not exactly lost, but magic still, an attraction that is forever coming but never quite here? Could it be that the best way to preserve film culture is to make sure that at least a few great movies stay on the other side of the wind?