I made a deal with the deer: I plant double, you take your half, I take my half. They broke the deal before the ink was dry. Shoots of corn and beans, and later the flowers of peppers both hot and sweet — cayenne, tabasco, California Wonder — the deer went deep into my half for any tender offering. Even my heirloom zinnias. So I built a standard three-rail fence around the garden. Three rails, though, are like Tinkertoys to deer. They jumped my ridiculous fence and were back in the garden early the next morning, taking out a further swath of summer’s promised bounty. I nailed iron posts to the fence corners for elevation and then strung plastic mesh. They jumped into the mesh and, I think, immediately back out; the mesh apparently frightened them. I restrung it, and the garden became mine again. Until a mockingbird swooped down on me. I was transplanting Burpee’s Big Boy tomato seedlings with a small shovel when he attacked, and I threw the shovel at him. That was my first engagement with this, or any, mockingbird.

He pushed his claim to high office again when the Big Boy transplants had matured and began to fruit. The least hint of red was his beacon. He would peck into the red just enough to ruin the entire tomato. And so I moved my tomato patch into a small abandoned dog kennel and put the magic plastic mesh over the top to keep him off my Big Boys, Brandywines, German Johnsons, Black Krims, Mortgage Lifters, and Mr. Stripeys. This infuriated him, and he began to make dedicated swoops at me when I went out in the morning to get my newspaper.

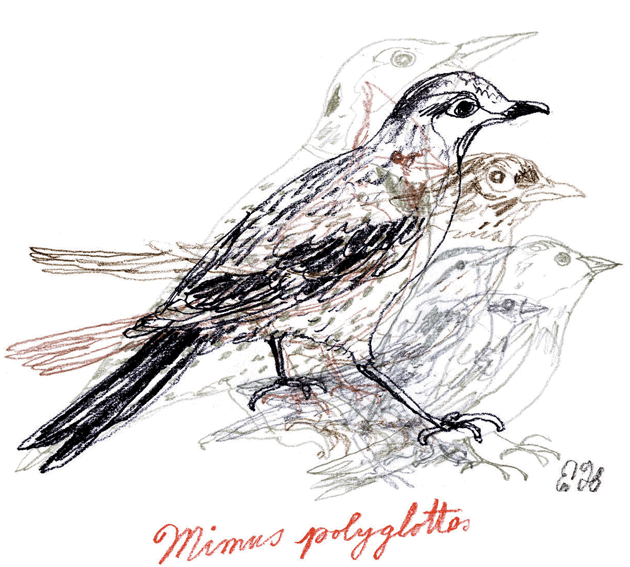

According to the website Birdzilla, the mockingbird is very aggressive when it comes to defending its territory and nest, attacking even snakes, cats, and humans. The mockingbird is also a talented vocal mimic, Birdzilla tells us, and can imitate the songs of many other birds, as well as manmade noises such as car alarms or squeaky pumps. I have read, too, that it can mimic the bark of a dog. Before federal laws were passed to protect native birds, so many mockingbirds were captured for the pet trade that they became scarce across much of their natural range.

This one is not scarce across any part of my range of four acres. And it is clear from his derring-do and claim to dominion that he regards himself in heroic measures. Beowulf’s windblown and birdlike ship comes to mind — here, in Seamus Heaney’s translation:

Over the waves, with the wind behind her

and foam at her neck, she flew like a bird

until her curved prow had covered the distance

and on the following day, at the due hour,

those seafarers sighted land,

sunlit cliffs, sheer crags

and looming headlands, the landfall they sought.

He is the very ship that has plied its way through difficult waters to reach the sunlit cliffs, sheer crags, and looming headlands that are now transformed into my yard and vegetable garden. But he is outraged by the traditional gender assignment. The ship, a she. That’s part of how I account for his animus. The other part is that he’s just an asshole.

Among his other assumptions of regnancy, he has taken over my birdbath, which is a tidy copper basin designed for the feathered friends to whom I have extended a welcome: my Carolina wrens — tea-kettle, tea-kettle, tea-kettle-tea, or sometimes simply toodlewee; the titmice — Peter-Peter; the goldfinches — per-chick-o-ree or potato-chips, also zwe-zeeeee; and my favorite, the common sparrow — come-come-where-where-all-together-down-the-hill. (Voices rendered by the Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds.) In their bathing, these favored birds of mine have a delicate economy of motion, soft flicks and twitches, conserving water as if they know others are waiting in line. The mockingbird’s bath is an orgy of thrashing and writhing about. When he has finished, one of the innocents alights on the rim of the basin and looks with disbelief at the thimble of water remaining.

And so daintiness and restraint are not qualities inscribed in the mockingbird psyche. Nor is reason. Mockingbirds will attack their reflection in a window, hubcap, or mirror, often with such intensity that they injure or kill themselves. My mockingbird went at himself for hours in the side-view mirror of my Ford Ranger pickup, repeatedly challenging the invader with what the Audubon guide describes as a harsh chack. (To be fair, the bird is capable of music, but is it finally his? The songs of thirty-six other species were recognized from the recording of one mockingbird in Massachusetts. Serious personality disorder there, or unrelenting guile.)

As for injury and death in general, those losses are part of the natural order of a bird’s life. Usually it is death from above. Have you ever seen a bird’s eyes not constantly parsing the sky? Landward there are cats ready to pounce. And other threats you wouldn’t dream of. A black snake climbed a column on my front porch and ate the eggs in a nest my sparrows had built on the overhead beam. The natural order, I figured. Not that I wasn’t chilled to see the snake on the beam above me, its overlapping coil gleaming ebony in the morning light. I poked it down with a shovel and took it to a thick winter-honeysuckle bush at the edge of my yard. I wanted to keep it around to eat the field mice and rats that had my garage in mind. The bulge of three sparrow eggs in the snake’s body was unmistakable.

Other sparrows had a nest in the bend of a downspout just outside one of my front windows. The nest was at eye level with the window, and I would stand there to watch the mother bird feed her four peeps. The day after I delivered the black snake to its safe haven, I looked out to find the nest empty. On the ground by the downspout were the dead bodies of two of the peeps. These were not fledglings, and I reasoned that the snake had come from the honeysuckle, had its fill of the two other baby sparrows in the nest, and then dropped these two to the ground. Or perhaps they had attempted flight.

So it goes. The snares and foils are many. Birds mistake the large windows on either side of my house for open passages and fly into them. I can hear their bonks as they hit the glass. I go out and try to help them get reoriented. A gorgeous yellow-shafted flicker wobbled around for twenty minutes or so after I gave it a gentle massage, and then took flight into the trees bordering my creek. Doves hit particularly hard; they are fleet and sometimes don’t recover from the collision with what looks to them like plein air. One afternoon I heard an unusually forceful hit and went out to find a dead dove on the grass. I plucked the feathers, freed the breast, and took it inside. Sautéed in butter with a sliver of garlic and hint of thyme, it was three-star Michelin, five-toque Gault et Millau.

More recently a pine siskin collided with a window. As with the dove, I was unable to revive it. It reminded me, though, of the ortolan, a bunting that some French gourmands drown in Armagnac, pluck, roast, and eat whole. I couldn’t bring myself to eat the little pine siskin, not even if prepared in the manner of my dove. As for the ortolan, European Union member states have banned the deliberate killing or capture of these birds because of their endangered status. The French have been lax in enforcing the ban, and poachers continue to trap this sparrow-size bird. Diners cover their faces with linen napkins and eat the entire bird, though the less venturesome forgo the head, beak, and feet. The covering of the face is said to have been initiated by a priest (friend to French gourmand Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin), who did so to hide his gluttony from God.

I have followed a red-shouldered hawk — kee-yeeear — from the time he was a fledgling. He was in a black walnut tree at the border of my property when I first spotted him, and for the past few years I have watched through binoculars as he drops down precipitously on field mice. He will also eat grubs. And occasionally I find clusters of fluffy gray feathers in the grass, but I do not know if he or some other raptor has intercepted a flying dove. That would be no small feat. My mockingbird will attack other birds, and me, but he does not mess with this hawk. I was elated recently to spot my hawk and a female, only just arrived, resting together on a piece of sculpture in my back yard. I am hoping for young red-shoulders soon from their pairing.

My sculpture appropriates an iron wheel rim from an old farm wagon. Welded within the circle of that rim is a sinuous S of metal, making for a yin-yang effect. Bluebirds often perch on the sculpture, though always solo for some reason. The smaller birds tend not to perch there, perhaps because the wheel rim is too wide to afford a secure purchase. Or maybe the mojo of the mandala is too much for them. I don’t know. I am not a birder by any stretch, but I can sit and watch these creatures — in the birdbath or on the wheel rim or in flight — for long periods of time, rapt with fascination and wonder.

In all of this behavior, I detect a manifest social order in the bird kingdom, and I don’t mean simply a pecking order. The cowbird, for instance, is a brood parasite. It lays its eggs in the nests of songbirds. Some of them will reject the cowbird egg; others will lay down a new nest lining over it. But most will rear the young cowbird, which matures quickly at the expense of the host’s young, pushing them out of the nest or taking their food. Added to this parasitic behavior is the cowbird’s lack of any prepossessing physical attractiveness, at least to my eye. I watched a brown-headed cowbird alight near three of my common sparrows on a section of fence. Sort of like Charlie Chaplin disciples, the sparrows edged away in a comical sideways avoidance maneuver. The cowbird tiptoed awkwardly along the fence railing after them, trying to seem nonchalant but making an obvious bid to be a buddy. He edged over, they twiddled a few steps away, he edged over again, and the sparrows finally took flight. The cowbird remained there, alone and gripping the fence rail in ignominy.

I am not going to kill the mockingbird. Truth to tell, I have become amused at his antics. Yesterday morning I walked out toward my garden and he took flight from the fence. I have a screenhouse that is elevated on wood pilings, but there is only a three-foot space between its floor beam and the ground. The mockingbird made a straight course for that restricted opening and flew under the screenhouse and out the other side. Show-off. But maybe a hint of détente. He didn’t swoop down on me.

In To Kill a Mockingbird, Miss Maudie Atkinson tells Scout that “mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

Up against Miss Maudie’s sentimentality — and my own, in tracing the delights of my little birds — is an alternative truth. In the closing scene of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, there is a robin on a tree branch. The robin is central to a dream that Laura Dern’s character has had, and she interprets its return as the return of love. The scene is controversial, but I regard it as ironic. The robin (which, by the way, is a stuffed robin) has a bug in its beak, and its gaze registers nothing resembling love. Dern’s character is in denial of the reality of predation, dramatized in chilling detail by Dennis Hopper’s character as he inhales whatever it is, helium or nitrous oxide, from a face mask and enters a deeper chamber of his psychosis. And so what are the truths that birds bring to us in their perches and flights, and in our dreams of them?

In the Venerable Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (circa 731 a.d.), we are told of a bird who flew into a festive hall from the night of rain and snow outside, only to pass into that night again through a window on the other side of the hall. Such is our brief passage through life. It is from darkness into darkness, unknown on either side. But there is the warmth and light and joy and sadness of the hall. In my imagination it is a mead hall, with venison and pheasant, quail, the pig on the spit, dogs asleep by the ancestral fire, bold women and men our friends, laughter, song, weeping over spoken poems of human error and downfall. We are that bird in flight. But we are not alone. Flying with us are the wrens and titmice, the goldfinches, my two hawks, the common sparrows. Come! Come! Where? Where? All Together Down the Hill!