All the way, at odd times, far off, with neither sense nor sequence, the guns have sounded almost like the noises of peace — blasting or pile-driving. Now, outside the village, as the ambulance comes out upon the hill, they sound for the first time like the noise of battle, much nearer and much more terrible. Now, too, far off, as the car runs in the open, the drivers see the star-shells going up and up, and bursting into white stars, and pausing and drifting slowly down, very, very slowly, pausing as they come, far apart, yet so many that there are always more than one aloft. They are the most beautiful things in modern war and almost the most terrible. Often they pause so long before dying that they look like the lights of peace in lighthouse and city beacon, or like planets in the sky.

In this open space the drivers can see for some miles over the battlefield. Over it all, as far as the eye can see, the lights are rising and falling. There is not much noise, almost no continual noise, but a sort of mutter of battle with explosions now and then. Very far away, perhaps ten miles away, there is fighting, for in that quarter the sky glimmers as though with summer lightning; the winks and flashes of the guns shake and die across heaven.

In this open space the drivers can see for some miles over the battlefield. Over it all, as far as the eye can see, the lights are rising and falling. There is not much noise, almost no continual noise, but a sort of mutter of battle with explosions now and then. Very far away, perhaps ten miles away, there is fighting, for in that quarter the sky glimmers as though with summer lightning; the winks and flashes of the guns shake and die across heaven.

One side of the road here is screened with burlap stretched upon posts for half a mile together; otherwise daytime traffic on it would be seen by the enemy. Some of the burlap is in rags and some of the posts are broken; the wreck of a cart lies beside the road, and in the road itself are roundish patches of new stones where shell-holes have been mended, perhaps a few minutes before. This part of the road jingles like the rest with traffic, though here, for some reason, there are fewer motor-lorries and more horse-wagons. Here and there are working parties filling up shell-holes with stones. That piece of road is always much shelled in the daytime.

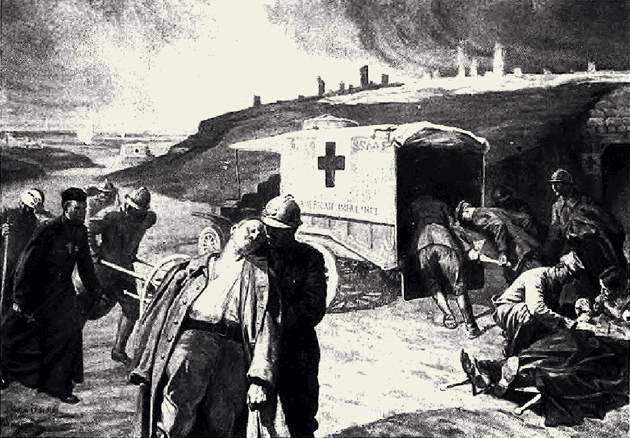

By this time the moon is riding the night in beauty. The ambulance passes from the danger patch into a desert with neither hedge nor tree upon it. In the moonlight one can see the fields on each side of the road for perhaps a quarter of a mile, as in a summer dusk. One glance at the fields is enough to show that they have been bedeviled by the hand of war. All the countryside shows like a warren, with holes and tossed-up earth, as though rabbits as big as horses had been burrowing there for years. The earth lies scooped up in lines and heaps and hillocks, paler than the grass in this light, but all irregular and meaningless and useless. Near the road the pits and tossings of the earth run into one another at every yard, and out of them project the bones of their victims — carts with their wheels in air, the skulls of horses, the bonnets of ambulances, and splinters that might have been anything.

Once, for three weeks on end, day and night, all that road and the land beside it was rained upon by shells of every kind till it became as it is now, blasted from all likeness to land. There are not five consecutive unscarred yards upon any part of it. It is torn and burrowed in and pitted with the pox of war; the flesh of the earth is eaten and blown away and the bones of the solid world laid bare. At seeing this for the first time in its fullness a man has just that sense of infamous desecration which comes to him when he first sees wounded men brought in from the battlefield. During the weeks of that fury the men and horses that were killed upon that land were buried and unburied daily many times, and torn at last to dust and laid with the dust.

From “The Harvest of the Night,” which appeared in the May 1917 issue of Harper’s Magazine. The complete essay — along with the magazine’s entire 165-year archive — is available online at harpers.org/fromthearchive.