Early one morning in July, while hiking through the mountains of eastern Bosnia, I came upon a warehouse that was partially hidden by a clutch of beech trees. The long, flat concrete edifice was stippled with bullet holes, and across the front were a number of bluish posters, each with an airbrushed portrait of Vladimir Putin as well as a tagline in Cyrillic lettering: eastern alternative. I was walking with Ethan Putterman, an offbeat, white-haired professor who was born in Los Angeles and teaches Rousseau at the National University of Singapore. As we peered through a gate that hung in front of the entrance, Putterman said to me, “Do you know what this is?”

A warehouse in Kravica, Bosnia and Herzegovina, where, in 1995, 1,300 Bosniak men and boys were executed, July 10, 2015 © Matej Divizna/Getty Images

I had met Putterman only a few hours earlier, on the trail of the annual peace march that retraces, in reverse, the route taken by thousands of Bosnians who fled the town of Srebrenica during the Bosnian War. That morning, the third of the march, we had set out from the village of Pobudje with several thousand people. When we reached Krainovici, a scattering of homes that was too small to register on a map, Putterman and I had followed the path down a thicketed descent and ended up in the yard of a pale stucco house. The family who lived there served us coffee in plastic cups. After we rejoined the trail, picking a course through the blue-green hills, whose gentle, sinuous lines had gone bleary in the midsummer heat, we found that we’d lost sight of the march.

A wrong turn had delivered us to Kravica, and to the warehouse — where, Putterman told me, more than a thousand Bosniak (Muslim) men had been murdered in the summer of 1995. When Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence from Yugoslavia, in 1992, an amorphous three-fronted war broke out among the new country’s Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats. Starting in the spring of that year, as many as 50,000 Bosniaks sought refuge in and around Srebrenica, an alpine town of placid houses and boxlike socialist buildings that the United Nations established as a safe area in 1993. Despite the U.N.’s presence, the armed forces of the Bosnian Serbs, which were supported from Belgrade by Slobodan Miloševic, laid siege to Srebrenica for three years. They overtook the starved, suffocated town on July 11, 1995, and two days later transported some 1,300 captured Bosniaks to the warehouse in Kravica. Once the warehouse was full, the Serbs opened fire, including with rocket-propelled grenades, and executed the men throughout the night.

The posters we saw on the front of the warehouse were a plea to Putin to block a proposed U.N. resolution that would formally acknowledge that the mass killings at Kravica and around Srebrenica had constituted genocide. Evidently the appeal had been successful; two days earlier, Russia had vetoed the resolution. While Putterman and I were taking pictures of the structure — he with his iPad, I with my phone — a police officer in a navy-blue uniform appeared through the trees. He shouted at us, pointed unhappily at Putterman’s iPad, and waved us off in the direction we’d been heading before. After a few minutes of walking more quickly than we tried to let on, Putterman said, “Don’t turn around, but he’s following us.”

It wasn’t long before a police cruiser drove up from behind us and cut off our path. The officer checked our passports and asked to see the iPad. Though Putterman swiped carefully away from the photos and video he’d just taken, the policeman opened the back door of his car and indicated that we should get in. He drove us to a crossroads, left us in his airless car while he had a long conversation with his chief, and finally dropped us off at the bottom of a hill. When another car sped toward us, Putterman and I ducked into a cornfield; we decided it was best to take a taxi to Potocari, a hamlet a few miles away. The peace march was due to arrive there later that afternoon.

On July 11, 1995, the day that Srebrenica fell, some 25,000 Bosniaks fled to Potocari, where a detachment of U.N. troops from the Netherlands was stationed in an old battery factory. The mission of the Dutch battalion was to protect the civilians in the Srebrenica enclave, but the peacekeepers denied entry to many of the refugees who arrived at the compound. Those who were allowed inside were soon turned over to the Serbs. Ratko Mladic, the Serb military chief, entered Srebrenica virtually unopposed, and over the next seven days his forces murdered more than 8,000 Bosniaks, nearly all of them men and boys, in the Kravica warehouse and in fields and farms around the region. (Mladic was arrested in 2011 and extradited to The Hague, where he is on trial for genocide and crimes against humanity.)

Eight thousand is an ungraspable number, but the boundless plane of tombstones — white marble obelisks inscribed with Arabic epitaphs — that today curves up the hillside of Potocari gives some sense of the magnitude of the crime. This year, 136 fresh graves were dug for victims whose bodies had been discovered since the 2014 commemoration. (In many instances, the Serbs exhumed and reburied their victims to hide evidence of the killings.) One of them was for a man named Becir Velic, from the town of Cerska, just outside Srebrenica. His grave was marked 1939–1995. On the morning after the peace march arrived in Potocari, twenty years to the day after the fall of Srebrenica, I watched the men of his family kneel around a hole in the earth and lower the casket. They folded themselves over in prayer, while the women, their heads covered with white scarves, stood behind the men and cried.

At the battery factory, Land Rovers pulled up and disgorged the designated VIPs for the day’s commemoration ceremony: the French ambassador and the Dutch foreign minister, the deputy secretary-general of the United Nations, and, finally, Madeleine Albright and Bill Clinton. When the prime minister of Serbia, Aleksandar Vucic, arrived from Belgrade, the press shoved cameras in his face. Vucic and Clinton shook hands. The dignitaries gave speeches that followed a predictable pattern — expressions of sympathy and regret followed by exhortations to future togetherness — and made a brief cavalcade through the cemetery, where they laid flowers at a monument, pausing for the pack of cameras that tailed them. As Vucic passed among the gravestones, protesters threw rocks and plastic bottles at him, which some Serbs would later describe, somewhat cynically, as an assassination attempt.

One person who was not in Potocari for the ceremony was Pedja Kojovic, the president of one of the country’s newest political parties, Naša Stranka (“Our Party”). A former journalist and a sometime poet, Kojovic, who is fifty, has shoulder-length brown hair that he parts down the middle. He speaks with a slight, thoughtful reticence. On non-parliamentary days, he wears a tight black T-shirt and jeans, a holdover from the years he worked as a cameraman for Reuters. A week before the peace march, I met him in one of Sarajevo’s ubiquitous cafés. We sat at a counter that looked out onto the brutalist structures and neo-Renaissance buildings in faded greens and pinks that alternate along Marshal Tito, a boulevard that runs through the city center. Kojovic had plans later that month to visit the village of Doljani, where he’d come across the aftermath of a massacre in 1993, and he had loudly condemned Russia’s veto of the U.N. genocide resolution. But he expressed a wariness about the ways in which various groups had appropriated the annual Srebrenica ceremony for their own purposes. “I don’t want to turn it into a marketing campaign,” he said. In the decades since the war, commemorations in Bosnia have become a new battleground, where feuds over narrative — who was guilty, who was victimized — are played out in grotesque pantomime. Srebrenica lies deep inside a part of the country that is now governed by the Bosnian Serbs, and, as I discovered, the authorities there have been known to make trouble for visitors who come to pay tribute to those who died in the genocide. “When we are able to recognize that all victims were our victims,” Kojovic said, “that will be the first step in reconciliation.”

Kojovic spent the first half of the 1990s reporting on the wars of independence that accompanied the disintegration of Yugoslavia: he followed them first to Slovenia, then to Croatia, and finally back home to Bosnia. Aleksandar Hemon, the novelist, who was his roommate at the time, described for me recently the tense months leading up to the Bosnian War, which had brought an almost frantic pursuit of pleasure. According to Hemon, Kojovic had fallen in love with a woman from Istria, in Croatia, and “he would lie back, with his eyes closed, and repeat these Istrian words that he found strange. And the word that he would say was something like ‘mruljice.’ And I’d say, ‘What the fuck is mruljice?’ He told me it was a dustpan. The least romantic object in the world. But he would just be on his back repeating the Istrian word for ‘dustpan.’ ”

Reality quickly upended their late-twenties oblivion: when Kojovic was dispatched to Croatia, in 1991, he was detained and tortured by the Croatian army. “He was all beaten up,” Hemon told me. “He would spend an hour in the bathtub soaking his bruises. He was so destroyed he couldn’t sleep.” Kojovic’s father, a Serb, was an eye surgeon who worked at the hospital in Bosniak-controlled Sarajevo throughout the war; near the end of the conflict, he was arrested by the Serbs and put in a concentration camp for aiding the enemy. After he was released, four months later, he and his family, including Pedja, left for the United States.

Kojovic had been working for Reuters in Washington, D.C., for twelve years when, in 2007, he returned to Bosnia to promote a book of poems he had written. In Sarajevo he had coffee with Danis Tanovic, a filmmaker who won an Academy Award at thirty-three for his first feature, an absurdist reverie on the Bosnian War, and Dino Mustafic, a popular theater director. Over the course of a long conversation, they found that they were all troubled by the paralysis and corruption of the country’s postwar political system. Kojovic moved back to Sarajevo the following year with plans to read and write poetry, but he ended up joining Tanovic, Mustafic, and a multiethnic group of artists and intellectuals who were disappointed with the Bosnian left and had decided to run in local elections as Naša Stranka. Tanovic lent the party the considerable heft of his name — “It was like Danis was opening a nightclub, and ten thousand people showed up the opening night,” Kojovic said — and Mustafic brought the political connections.

The founding members of Naša Stranka spent the summer and fall of 2008 visiting sixty towns around Bosnia. “We had zero cash, so we used our friendships and authority to provide some sort of campaign,” Kojovic told me. They incurred a hundred thousand dollars of debt. “I would go and say to a friend who runs the printer’s shop, ‘Hey, can you print us fifty thousand posters of this? I’ll pay you sometime.’ ” But they all felt that reform could only happen from within the system. “It couldn’t be done by writing open letters or civil society, that kind of stuff,” Kojovic said. Given the party’s limited time and resources, the members of Naša Stranka counted it a considerable victory when they won nearly 15 percent of the vote in Sarajevo that fall.

The horrors of Srebrenica helped to expedite a peace agreement that was finalized in November 1995, in Dayton, Ohio. The Dayton Accords were a welcome and necessary accomplishment, but in the twenty years since, it has become clear that the major powers that conspired to extract peace — the United States, the United Kingdom, and France, along with the U.N. — were not caught entirely unaware by what had happened in Srebrenica. Indeed, U.S. intelligence agents had seen, nearly in real time, satellite images of the slaughter. According to some critics, Srebrenica was sacrificed by the leaders of the Western powers for the sake of a peace deal.

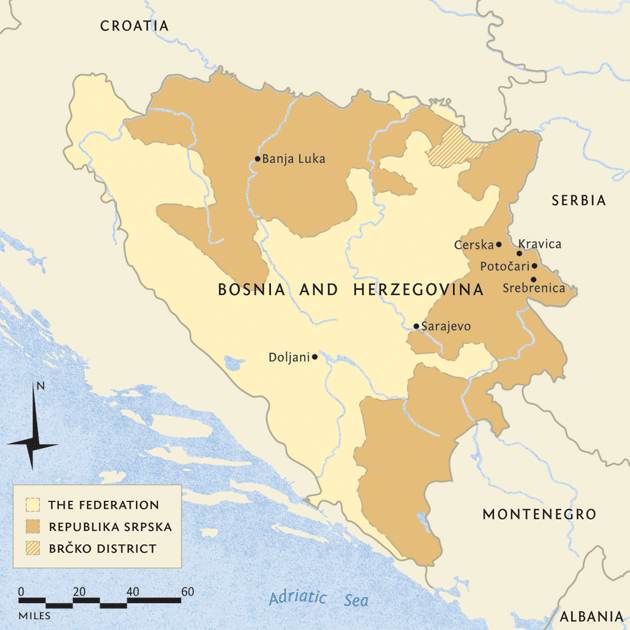

The Dayton Accords stopped the Bosnian War, but because the deal was hammered out before there was a clear military victor, it relied on a complicated patchwork of ethnically organized governments that satisfied everyone and no one. Most saliently, it divided the country of Bosnia and Herzegovina into two quasi-autonomous “entities,” which coexist in a turbulent union. The Serbs were permitted to maintain much of the territory that they controlled at the end of the war — 49 percent of the country — in an entity that they called Republika Srpska. Meanwhile, the Bosniaks and the Croats were given control of the other entity, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, known colloquially as the Federation. Together the entities form a sort of bicameral nation, which is governed by a three-member presidency that consists of one Bosniak, one Serb, and one Croat. (The Brcko District, in northeastern Bosnia, formally belongs to both entities but governs itself.)

Throughout the conflict, Serb and Croat leaders had lobbied to divide Bosnia along ethnic lines, but Richard Holbrooke, the American diplomat who was the chief architect of the Dayton Accords, felt that such a solution would legitimize the ferocious Serb nationalism that had incited the war. Even so, he would later look back with a measure of regret on some aspects of the partition: “We underestimated the value to [the Serbs] of retaining their blood-soaked name,” he wrote in his memoir. The country that Holbrooke and his team ultimately fashioned is extraordinarily complex: today there are fourteen separate governments, each with its own ministries and parliament, for a country of 3.8 million people.

Many Bosnians blame Dayton for their country’s present situation, but the principles that underlie the agreement can be traced to the fall of Communism. When the country declared independence, it was the most ethnically diverse of the former Yugoslav republics: Bosniaks made up 44 percent of the population, Serbs 31 percent, and Croats 17 percent. Leaders of the new nation thought that each of the three so-called constituent peoples of the country should be represented by a single political party, a system that remains, for the most part, in effect today. As Kojovic told me, the leaders believed that “there would be no division within ethnic groups; all Muslims will vote for the Muslim party, and all Croats for the Croat party. For them, that was the multiparty system.”

Some of the faults of the system are revealed in its idiosyncrasies. In postwar Bosnia, a citizen can claim full rights only by declaring himself a member of one of the three constituent peoples. Though Kojovic is unofficially as multiethnic as his party, and indeed his country — his mother is Croat-Bosniak — he is, as far as the government is concerned, a Serb like his father. What’s more, he explained, each member of the presidency must be a resident in the part of the country that “belongs” to his ethnicity. “I cannot be a president of Bosnia, because I’m a Serb who lives in the Federation,” he said. “I would have to move to Republika Srpska. Imagine if there was a law in America that says, if you’re Hispanic and live in Texas, you can be the president of the United States. But if you’re Hispanic and live in Washington, D.C., then you can’t. Everyone would think the whole country’s a joke.”

Much of what was settled at Dayton wasn’t designed to be permanent, but the agreement created so many checks and balances that change has been extremely difficult to come by. “When you propose an ethnic solution, you create new problems,” Jasmin Mujanovic, a political scientist at York University, in Toronto, told me. “Twenty years down the line, you have a generation born into that system that believes it’s the only possibility.”

Naša Stranka was founded with an eye toward breaking the logic of Dayton. The party’s founders were convinced that the stranglehold of ethnicity in postwar Bosnia had made the country’s corruption intractable. Albin Zuhric, the party’s general secretary, suggested that even Sarajevo’s water restrictions could be blamed on ethnic politics: “For twenty years, it wasn’t the most competent people that we employed in the companies that supply water to most parts of the city. It was the people that the three ethnic parties put there because they were loyal.” As Kojovic put it, Naša Stranka “wanted to introduce a political option that’s based on the political options that democracies are based on — on ideology, not ethnic or religious background.”

Though Naša Stranka’s results in the 2008 election were respectable, the party encountered trouble in the national elections two years later, when it formed a controversial coalition with a party based in Republika Srpska. Tanovic won a seat in the regional parliament, but Naša Stranka was severely punished by voters, and it nearly disbanded. (These days, Tanovic and Mustafic have mostly returned to their art; according to Kojovic, “the gravity of their work turned out to be stronger” than the pull of politics.)

In its most recent national election, in October of last year, Naša Stranka had its best showing yet, and this summer the party provided a crucial vote for a significant labor-reform law. Even so, Kojovic acknowledged Naša Stranka’s limited presence within government bodies. He insisted that some of the party’s most important accomplishments have happened outside institutions. It supported an unpopular decision to permit a commemoration for a massacre of Serbs in Sarajevo, and has defended LGBT interests — two controversial positions, for which its members have suffered in the voting booth. “Naša Stranka is like a MacBook Air with no USB port; they’re technologically two steps ahead of reality,” Florian Bieber, a professor at the University of Graz, told me. Kojovic looked at it differently. “There are writers for the public, and there are writers for other writers,” he said. “And we are in part a party for other parties.”

Many photographers and filmmakers who covered the war in Bosnia found that the most effective way to communicate the suffering of Sarajevo was to capture it in the winter. In images of the besieged city, snow lining the concrete modernist apartment blocks of downtown sapped all color from the frame. Sarajevans who’d had the windows blasted out of their homes by mortar shells endured four Januaries with sheets of plastic over the gaps in the walls. There was no heat, or electricity, and people slept in ski gear. Hardly a tree was left intact.

These days, Sarajevo is best encountered in the summer. At sundown, a dusky haze settles into the skyline, and then darkness descends on the town center, which runs along the Miljacka River at the base of a green valley, before the surrounding mountain homes light up the metropolis from above. During Ramadan, the city performs a ritual each evening: a cannon sounds to signal the end of the day’s fast, and the sidewalk tables in Bašc aršija, the Ottoman-era old town, fill with Sarajevans for the iftar meal — flat somun bread, Bey’s soup, burek pastries with meat, dolmas, and baklava served with Bosnian coffee or tea. Afterward, people stroll through the neighborhood’s narrow alleys and into the Ozymandian lanes of the adjacent Austro-Hungarian quarter. The smell of sweet tobacco hangs over the cobblestones, and covered women pause to snap iPhone photos of girls in harrowingly tight dresses.

Rebecca West, who compulsively chronicled the Balkans in the 1930s, was enraptured by the “air of immense luxury” she found in Sarajevo, and its “unwavering dedication to pleasure.” But West also noted that this atmosphere was, “strictly speaking, a deception, since Sarajevo is stuffed with poverty of a most denuded kind.” A war, a socialist regime, and another war later, Sarajevo’s festive airs are buoyant as ever; yet the paradox that West identified endures. When the Dayton Accords were signed, many analysts projected that Bosnia’s economy would recuperate in five years if the new nation did everything correctly. Twenty years on, the country’s inflation-adjusted GDP is still below prewar levels. Unemployment stands at around 40 percent, with youth levels just above 60 percent, and the country is by some calculations the poorest in Europe.

The situation poses a dilemma for young Bosnians especially, many of whom want to help revive their country but don’t want to waste their lives in a system that seems incapable of making progress. “There are so many creative people here,” Dennis Gratz told me one afternoon at Naša Stranka’s headquarters. Gratz is a former president of the party, and, like Kojovic, he now holds a seat in the parliament of the Federation. A thirty-seven-year-old lawyer and novelist, he wore New Balance sneakers and a crisp oxford shirt. “There are parts of Sarajevo where you feel like in Williamsburg. But this system drives you mad. It makes you hate — first yourself, and then the rest.”

I caught up with Gratz again later, one evening after iftar. We sat on the patio of an Italian restaurant in a courtyard off Marshal Tito, across the street from his law practice. Sarajevo is a compact town, and if you were to spend enough time idling in a café — as many people do — “the whole city,” Hemon has written, “would eventually circulate past you.” At our first meeting, Gratz had talked spiritedly about the travails of Greece’s Syriza, which was a few days away from a referendum on the terms of a proposed European bailout. Five years ago, the two parties occupied comparable roles within their respective political landscapes, though Naša Stranka’s economic program is considerably more centrist. About an hour into that conversation, Gratz informed me that he was observing Ramadan, and hadn’t had anything to eat or drink. Now, adequately nourished, he was even more sardonic. “It’s so easy to solve the Greeks’ problems,” he said with a smile. “I would like to know how to solve our own.”

Before joining Naša Stranka, Gratz had never voted. “I was one of these educated people who are disgusted by politics,” he said. Dino Mustafic eventually persuaded him to get involved. In the early days of the party, Gratz told me, “it was very sort of intellectual, like, let’s meet for coffee, let’s get drunk and discuss politics. But we had no idea what we were getting into.” After the first election, Gratz went to New York for a year. He returned to Sarajevo in 2010, just in time for the party’s disastrous performance in the national elections; the opposition “cut us in pieces,” he recalled. “But we could not just stand by and do nothing.” Gratz was unsparing in his lament: “There is no democracy here. Politicians have access to money, they are deeply corrupt, and every aspect of public life is criminalized and morally so sold, so compromised, that it is almost impossible to understand how we get along with it. The only reason why we are not Somalia is our geostrategic importance. We are far too much in Europe, and we simply are a problem to be dealt with.”

It is no small irony that the ethnic tensions the Bosnian political system was designed to stop have become a crucial mechanism in that system. Ethnic conflict, and the fear it elicits, serve as a potent distraction from Bosnia’s all-consuming kleptocracy. Milorad Dodik, who is now the president of Republika Srpska, the Serb entity, was a moderate when he was prime minister in the late Nineties. “If more leaders like Dodik . . . emerged, and survived, Bosnia would survive as a single state,” Richard Holbrooke wrote in 1998. Today, however, Dodik is one of the most belligerent Serb nationalists in the country; in June he railed against the proposed U.N. genocide resolution and declared Srebrenica “the greatest deception of the twentieth century.” According to Jasmin Mujanovic, of York University, “He figured out what the system rewarded.” Dodik has been threatening secession for years, and in July he proposed a referendum on whether Republika Srpska should continue to recognize the legitimacy of Bosnia’s judiciary system. Many analysts suspect that one of Dodik’s objections to the courts is that they would probably send him to jail if he fell out of power.

A week after the peace march, I took an early-morning bus to Banja Luka, the capital of Republika Srpska. I watched through the window as the pointed roofs of the houses in the countryside around Sarajevo gave way to the waved domes of the Serbo-Byzantine style. In Banja Luka I met Bojan Šolaja, a thirty-one-year-old who runs the city’s International Press Center. He had a buzz cut and wore a turquoise polo shirt, and he looked at me skeptically for most of our conversation. Behind us stood the city’s gold-crested Orthodox church, majestic but lonesome, in the middle of an empty square. Šolaja harbored a deep sense of victimization at the hands of the international community, and ran down a list of grievances that are shared by many in Republika Srpska: the Serbs had been blamed, wrongly, for starting the war; what happened in Srebrenica had been declared, falsely, a genocide; and now the Western powers were continuing to meddle, in typical imperial fashion, in affairs that no longer concerned them, as evidenced by the proposed U.N. resolution. “Why Serbs, why Srebrenica, why now?” he complained. He insisted that Serb interests would always be distinct from those of the Bosniaks. “They see Bosnia and Herzegovina as one country in the future. And that’s a problem,” Šolaja told me. “You will never have a Bosnian nation.”

Milica Plavšic and Aleksandar Trifunovic, Serb journalists who occupy the other end of the political spectrum from Šolaja, were in low spirits when I met them at their office in Banja Luka that afternoon. “My mother is an educated woman and a pensioner, and she doesn’t live so well,” Plavšic told me. “She knows about the corruption, and she doesn’t really like Dodik. But she chooses to believe him. There is so much fear.” Trifunovic accused Dodik of shuffling away enough money to take care of several generations of Dodiks. He alluded to recent demographic estimates that put the proportion of Serbs in the entity at about 90 percent: “Now you have a situation where Republika Srpska is possibly becoming ethnically ‘clean,’ and at the same time, many people say our main problem is Bosniaks or Croats. This kind of fear is the result of manipulation.”

It is very easy to fall in love with Sarajevo. People sit all day at the cafés along Ferhadija, the pedestrian promenade that runs into the old town, and sip sweet espresso. The city is laid out like a stratigraphic soil sample, and it displays the stunning architectural articulations, refurbished since the war, of five centuries of ruling cultures — Ottoman, Hapsburg, socialist. The many ornate mosques, churches, and synagogues lend Sarajevo a seductive cosmopolitanism. It’s no surprise, then, that the city has already been anointed the next great tourist destination, even though one need push only lightly for its allure to give way. The National Museum, one of the country’s most important cultural institutions, was shuttered for three years; it finally reopened in September thanks to an activist campaign. When I tried to visit the bright-yellow Holiday Inn, a Sarajevo landmark — it was built for the 1984 Winter Olympics, and became the informal headquarters for reporters and diplomats during the war — I found it padlocked, caught in the midst of bankruptcy proceedings.

Still, Sarajevo is substantially better off than the rest of the country. “Central Sarajevo is beautiful, everything looks good,” Nidžara Ahmetaševic told me at her apartment behind the old town. A ceramic bust of Karl Marx that doubled as a piggy bank looked at us from across the room while we ate ružice, a syrupy walnut cake, and drank rakija from a tall plastic bottle. Ahmetaševic, a forty-one-year-old journalist with elegantly short hair, criticized Naša Stranka for failing to address the destitution in the rest of the country. “Njihova Stranka,” she called it — “Their Party.” “You can’t be a political party in this country if you stay in central Sarajevo,” she said. “Would Barack Obama win if he stayed in Manhattan?”

Ahmetaševic was deeply involved in a protest movement that erupted in February of last year, when the public’s rage at the economic situation and corruption broke through the passive postcommunist political culture. Protesters were beaten by security forces, and demonstrators in Sarajevo and the northern industrial city of Tuzla set fire to government buildings. The burning gave way to plenums, public assemblies in which citizens put forward concrete demands and forced the resignations of several government officials — “a political theorist’s wet dream,” as Jasmin Mujanovic described them. “We need another wave of protests desperately,” Ahmetaševic told me. “We need people to feel what democracy is, to feel power. Everything is ruled over by politicians — banking system, schools, private universities, even shops belong to politicians. Our lives, in a way, belong to them.”

Just before I arrived in Bosnia, in late June, the Federation’s three-month-old ruling coalition had collapsed. The supposed reason was a dispute over control of state-owned companies, though as with everything in Bosnian politics, there were several murky layers of subtext. With no government to speak of, the Federation’s parliament lay empty for much of the summer, yet Naša Stranka still continued to draft new legislation. “Dennis is like the guy with the soccer ball on the field,” Kojovic said of Gratz. “Like, ‘Hey, where is everyone?’ ”

At the end of July, Kojovic and several members of Naša Stranka drove out of Sarajevo toward the rocky bluffs of southwestern Bosnia. For the first time in twenty-two years, he was returning to Doljani, the village where he’d discovered a massacre of Croats in 1993. At the time, he had been reporting for Reuters on a Bosniak military offensive in the region. “I came across it like in a Fellini movie,” he said. “There was a priest running through a field. He was completely lost. He told me that civilians were trying to get away.” The priest said that his parents were trapped in Doljani, and he begged Kojovic to drive him there. On the way, they came upon a field where there were several dozen lifeless bodies whose hands were tied behind their backs. The priest knew the victims, and he ran around the meadow, calling out their names. Kojovic took out his camera and began to film. The whole clearing erupted with a cry. Kojovic found the priest weeping next to the bodies of his mother and father.

Working as a war correspondent in other countries had been difficult enough, but it was even harder for Kojovic to rid himself of the trauma he had encountered at home. Now, two decades later, he walked around the clearing, to a place where a Croat couple had lain, and then to another, where he’d discovered two dead girls intertwined. The weather was the same as it had been in 1993, sunny and warm. He told me later that it was jarring to find the field without the bodies: “So strange to see this beautiful meadow on top of the mountains, whereas I remember it as an entrance to hell.” A Catholic service, part of a commemoration of the massacre, was held beneath a tent flying a Croatian flag. Kojovic said that during the ceremony the Croats in attendance had looked at one of the younger members of Naša Stranka and whispered that she didn’t know how to cross herself correctly. Unlike Srebrenica, Doljani rarely received outsiders, and the people there hadn’t imagined that non-Croats would come.

During the war, Kojovic often traveled back and forth across the front lines while following stories. “He knew people. He wasn’t too afraid,” Aleksandar Hemon said. “He would go farther than anyone else, to places that other people had no access to.” When I asked Kojovic how his experiences twenty years ago affected his work today, he told me that he had made a habit during those years of attending funerals on all sides of the fighting. Sometimes he went to so many in a single day that he would get confused about whether the ceremony he was observing was for a Bosniak, a Croat, or a Serb. “Not many people had the opportunity to see that, okay, we’re suffering here, but over there they are suffering, too,” he said. “There were small differences in the rituals, but when you see the faces of the people being buried, they look exactly the same.”