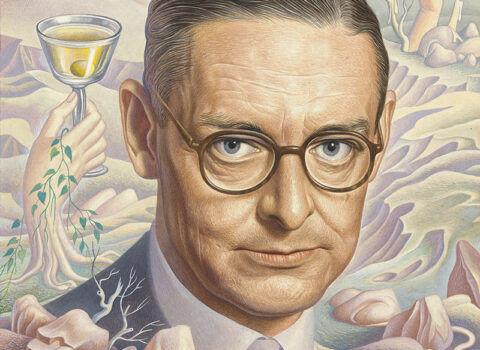

Discussed in this essay: John le Carré: The Biography, by Adam Sisman. Harper. 672 pages. $28.99.

At the height of the Suez Crisis, in 1956, the headmaster of Eton College, Britain’s grandest public — meaning private — school, invited Lord John Hope, a Foreign Office minister in Sir Anthony Eden’s Conservative government, to discuss the situation with his staff. A number of Eton masters, outraged by Eden’s invasion of Egypt, were thinking quite seriously, the headmaster had learned, about sending a strongly worded letter to the Times. Around a fifth of Conservative members of Parliament were, in those days, Old Etonians, including Eden himself, half of his cabinet, and Hope, who had recently joined the school’s governing body. So Hope would have understood that such a letter would not do. That, presumably, was the reason he agreed — in the middle of the foreign-policy disaster that would finally make it clear to Britain that it was no longer a freestanding world power — to put the case for attacking Egypt to a handful of secondary-school teachers.

In the matter of heading off a letter to the Times, Hope’s mission was a success, to the headmaster’s relief. But few of the angry teachers found the government’s line convincing, and the same held true in the wider world. When the Eisenhower Administration put a stop to the Suez adventure by threatening to cause a run on the British pound, it was hard for Britons to decide whether they felt more humiliated by Eden’s grandiosity and ineptitude or by seeing their leaders treated with the same kind of high-handedness that had been, in living memory, the British Empire’s stock-in-trade. Eden, a sick man, flew to Jamaica after the ceasefire and spent several weeks recuperating at Goldeneye, the writing retreat that Ian Fleming owned on Oracabessa Bay. Eden’s cabinet rivals used his vacation to mobilize against him — it didn’t help that Fleming’s wife, Ann, was known to be friendly with the Labour Party leader, Hugh Gaitskell — and within weeks of his return he resigned as prime minister to make way for Harold Macmillan.

Eden’s choice of Goldeneye had come about by chance. Fleming, an Old Etonian roué who’d worked in intelligence during the war, knew him socially but didn’t particularly like him. All the same, it says something about the tightly woven nature of Britain’s unreconstructed postwar upper class that the prime minister who’d come to personify the country’s rapid diminishment found himself borrowing a house from the writer who was doing more than anyone else to project a compensatory fantasy of secret British power. James Bond wasn’t yet big business at the time, but Fleming hit his stride the year after Suez, in From Russia, with Love, which was soon followed by Dr. No (1958) and Goldfinger (1959). As Simon Winder points out in The Man Who Saved Britain (2006), an entertaining study of the Bond phenomenon, these three books — Fleming’s best — “were written, published and hugely read during the final implosion of the old British imperial state with Macmillan’s post-Suez decision simply to bail out, at all costs, from empire.”

Bond mania peaked in the early Sixties, softening America up for the Beatles with the aid of an endorsement from John F. Kennedy and, beginning in 1962, the movies. As originally conceived, however, Bond was very much a creature of the backward-looking elite that welcomed Britain’s long run of Conservative governments, inaugurated in 1951, as an antidote to what he calls, in Thunderball (1961), “the cheap self-assertiveness of young labour.” Fleming’s patrician worldview — which made it natural for him to liken Bond’s relationship with a black sidekick to “that of a Scots laird with his head stalker” — was out of step with the younger British intelligentsia, who mostly spent the Fifties feeling suffocated by the apparently interminable rule of men who’d been officers in the First World War. In their different ways, such figures as the novelist Kingsley Amis, the playwright John Osborne, and the satirist Peter Cook came to define themselves against the kind of chap who ensured that his old school tie was correctly knotted as the world he’d inherited collapsed around his ears.

The task of bringing this more caustic sensibility to bear on Cold War spy fiction fell to John le Carré, whose early thrillers are, among other things, a rogues’ gallery of preposterous late-imperial types, all of whom are depicted as utterly empty inside. Call for the Dead (1961), his first novel, introduces an anti-Bond in the poorly dressed, bespectacled, frequently cuckolded person of George Smiley, who in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974) unmasks an old-fashioned romantic patriot in British intelligence as a Russian mole. It was Suez, the mole explains, that “finally persuaded him of the inanity of the British situation.” He also mentions that he hates America “very deeply.” Le Carré was well qualified to handle these themes, having served under his real name, David Cornwell, as both a spy and a teacher at Eton, where he’d been one of the indignant masters Hope had aimed to talk round. Almost from the start, he was said by reviewers to have wiped the floor with Fleming, who died in the summer of 1964. Six months earlier, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963) had reached the top of the U.S. bestseller list.

John le Carré came into being in 1960, when Cornwell was twenty-nine. (His first choice of pen name, Jean Sanglas, didn’t last long.) The pseudonym was penetrated four years later by Nicholas Tomalin of the Sunday Times, who identified its owner as a diplomat working in Germany. Le Carré denied being an intelligence officer — the spying stuff in his books was “just a gimmick,” he said — and continued to claim to be wholly untainted by the mischief of espionage until 1983, when he admitted to having “nosed around the secret world” to a reporter from Newsweek. Since then, he’s given numerous interviews, and written several substantial articles, including for this magazine, about his strange upbringing and brief career in intelligence, both of which he also fictionalized in A Perfect Spy (1986). As a result, a broad outline of his life and times has been available for decades, though Adam Sisman corrects a few misunderstandings — some of them promulgated by the novelist himself — in the pages of John le Carré: The Biography.

Sisman is an Englishman who’s established himself as a deft biographer of postwar Oxford grandees, though he’s probably best known for Boswell’s Presumptuous Task (2000), an account of the writing of the Life of Johnson. One of his earlier subjects, the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, knew his way around the secret world, where he gave offense by not concealing his low opinion of some of the minds he encountered, and it’s easy to imagine Sisman dealing expertly with Steed-Asprey, Fielding, Jebedee, and the rest of the donnish spymasters in the background of the Smiley novels. His credentials evidently passed muster with le Carré, who talked to him at length and gave him the run of his papers. According to the book’s introduction, however, le Carré “dislikes, or even disputes,” some of Sisman’s interpretations, and here and there the narrative feels constrained by negotiated reticences. Sisman says that he plans to publish a revised and updated version “in the fullness of time,” and he invites anyone with letters from le Carré to get in touch with him.

At the heart of the story the book sets out to tell is a sense that spying, performing, and writing fiction are more or less interchangeable activities. “When people ask me whether I am a spy,” le Carré said in a lecture in 1978,

I am tempted to reply with a hearty — “Yes, and since the age of five.” For a state of watchfulness must surely be the first requisite of a writer, as it is of a secret agent. A writer, like a spy, must prey upon his neighbors; like a spy he is dependent on those whom he deceives; like a spy he must somehow contrive to keep a distance from his own feelings and by doing so conjure up a package that will meet with the approval of his masters. Like a spy, he is not merely an outsider, but implicitly a subversive.

As these rolling cadences suggest, and as Sisman shows, there’s an actor, too, inside le Carré, who prides himself on his powers as a mimic and raconteur, his close attention to speech patterns and gestures, and his ability to manipulate an audience. Behind all this, in turn, there seem to be two attributes that le Carré often gives his double agents. One is an insatiable emotional neediness, of the kind that’s common among performers. The other is the insider-outsider’s need to be seen as fluent in a social code — in this case, that of the British establishment of the Fifties and Sixties — that he’s uneasily in love with and uneasily despises.

As A Perfect Spy inadvertently demonstrates, le Carré’s childhood might as well have been designed by a heavy-handed novelist with the idea of instilling exactly these qualities in him. He was born in 1931 in Poole, Dorset, on England’s southwest coast, to Ronnie and Olive Cornwell, a lower-middle-class couple from “Bible-punching” stock. Ronnie’s family were Baptists, Olive’s Congregationalists. This put Olive a rung above her husband on the social ladder, though both would have been marked down as “dissenters” by posh people, who would also have been alert to any trace of a West Country accent in their speech. Olive contributed to her younger son’s neediness — an elder brother, Tony, was born in 1929 — by leaving permanently when he was five. When le Carré next saw her, in his second year at Lincoln College, Oxford, she informed him that Ronnie had given her syphilis while she was pregnant with him, “and that as a result he had been born with pus dripping out of his eyes.”

Ronnie was essentially a con man, an investor-fleecing entrepreneur who built and lost successive property empires on the back of several creatively managed mortgage schemes. A charismatic speaker with the oratorical style of a respectable small-town evangelist, he got his start in his father’s insurance office, where he tapped into the provincial business networks associated with Freemasonry, the Rotary Club, the Baptist church, and the Liberal Party. He was well known in the bankruptcy courts and served time in prison in 1934 for “obtaining money and goods on false pretences.” Among a shifting cast of girlfriends and hangers-on, Ronnie brought his boys up in a string of big houses, which were abandoned now and then to ward off his creditors. His circle came to include sports stars, aristocrats, gangsters, police officers, MPs, and assorted “lovelies” — young women he’d introduce to important contacts. “We was all bent, son,” one of Ronnie’s associates told le Carré admiringly years later. “But your dad was very, very bent.”

It was important to Ronnie that his sons be gentlemen, which meant sending them to private boarding schools — first in outer London and Berkshire, then, in le Carré’s case, in Sherborne in Dorset. These institutions were run on Victorian lines with the aim of producing hardy, clean-living recruits for the officer corps and the colonial civil service. They were suffused by official Anglican piety and also functioned — as they still do — as incubators of class consciousness: le Carré learned to sneer at the rough tongues of “oiks,” while hugging to himself, he later said, “the shameful secret that my aunts and uncles spoke that way themselves.” Ronnie, who was often late with the school fees and once sent cases of gin and dried fruit in lieu of payment, presented a similar problem. During the Second World War, in which Ronnie didn’t serve, le Carré tried to save face with his classmates by hinting that his father had joined the secret service.

Sisman points to a children’s book called Oscar Danby V.C. (1916), about heroic espionage in the First World War, as the immediate inspiration for this fantasy. Le Carré’s reading soon moved on to Conan Doyle and Chesterton, and at Sherborne a school newsletter praised his free verse’s “musical rhythm and mastery of vowel sounds.” He did well academically, performed in school plays, and went out to bat for the cricket team. But the contradictions between his home and school lives overwhelmed him. In 1948, aged sixteen, in an attempt to escape both Ronnie and the public-school ethos, he left Sherborne to enroll at the University of Bern, in Switzerland. Homesickness took him to an Anglican church, where he was befriended by a tweedy couple from the British Consulate, who introduced themselves as “Sandy” and “Wendy Gillbanks.” They invited him round for sherry and steered the conversation toward the question of how he felt about service to his country. Before long, le Carré had agreed to travel to Geneva “and sit on a park bench with a volume of Goethe’s poems open on his lap” until a passing stranger uttered a code phrase.

An odd feature of le Carré’s ensuing double life — his new friends worked for the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), popularly known as MI6 — was its near-total lack of ideological passion. In Bern he was recruited to keep tabs on left-wing students, and when he reached Oxford, in 1952, he did similar tasks for MI5, the domestic arm of British intelligence. He left with a first in modern languages, and taught at a prep school and at Eton. In 1958 he became a full-time officer at MI5, dealing mostly with security vetting. Two years later he moved to SIS, which sent him to Bonn, West Germany, apparently to keep an eye on neo-Nazi groups. (He’s still tight-lipped about his duties there.) In 1964 he resigned and became a full-time novelist, his superiors having calculated that being the world-famous author of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold wasn’t altogether compatible with working as a secret agent.

At no point in Sisman’s account of these years does le Carré come across as a young man driven by fervent nationalism or anticommunism. That’s not especially surprising in a British context: though MI5 had its share of fire-breathing reactionaries, the services prided themselves on having officers who were less conservative too, and the U.K. had no equivalent of Joseph McCarthy or J. Edgar Hoover. “The justification for what we did” — that there was an active intelligence threat from the totalitarian East — “was one I accepted and still accept,” le Carré told an interviewer in 1999. Even so, it’s hard to square his record as a man of the left and a sour observer of the British establishment with the business of filing clandestine reports on his friends. Sisman’s solution is to follow his subject’s lead and to treat spying as a response to obscure inner urgings rather than as a purely instrumental activity. As in le Carré’s fiction, you get the impression that role-playing and having secrets became more absorbing than the ends to which they were supposedly directed.

The security services also presented themselves as a natural outgrowth of the elite educational institutions whose ways le Carré had absorbed since early boyhood. As such, they were a bulwark against his father, who’d gotten into the habit of whisking his household to Switzerland for free vacations laid on by gullible hoteliers. Ronnie was viewed with suspicion by every authority figure who crossed le Carré’s path. “I don’t like his father,” his prep-school headmaster informed his future teachers at Sherborne, where his housemaster, in turn, noted his “unsatisfactory home background” and urged him to “choose between God and Mammon.” At Lincoln, he came under the pastoral care of Vivian Green, a clergyman-scholar who served as one of the intellectual models for Smiley. (Sisman delicately describes this eccentric Oxford character, venerated for years by le Carré, as “someone whom one needs to have known in order to appreciate fully.”) Green stiffened le Carré’s determination to accept no more of Ronnie’s pilfered cash, and helped him find other sources of income.

Ann Sharp, whom le Carré married in 1954, when he was twenty-three, acted as another counterweight to his father. Like le Carré, she was a refugee from a broken family — a philandering father, a vacuously uninterested mother — and a product of English boarding schools. A would-be writer and — awkwardly for an embassy wife — a member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, she was uncomfortable with his easy charm and worldly Oxford friends. Both were sexually inexperienced when they met. “I have decided that in future I will let [him] touch my breasts, but nothing more,” she wrote in her diary during their long courtship. Le Carré seems to have felt a need to make her jealous, perhaps as a test of her unconditional love, and in due course he gave her good reason to feel that way. He was thrown off balance by the birth of their first child, in 1957, retreating to a monastery in Dorset for a week, and by the time they reached Bonn, where he had an affair with an unnamed woman, the marriage was in tatters.

Spying, too, began to feel stifling; le Carré increasingly saw it as a day job. He wasn’t alone in having outside interests: Maxwell Knight, MI5’s leading agent runner in the interwar years, was better known as a writer and broadcaster on ornithology, while his former deputy, John Bingham, a tubby Irish peer of strongly right-wing views, wrote thrillers. (In addition to inspiring some of Smiley’s tics, Bingham introduced le Carré to his first literary agent.) There were other writers at MI5, but none with le Carré’s greedy eye for the comic-opera aspects of British intelligence. MI5 was packed with faded “ex-colonial administrators,” as one of his characters puts it, who were considered less likely to think it un-British to steam open a fellow’s mail. Nubile young women, “traditionally . . . from upper-class families,” looked after the filing. The social tone was higher still at SIS, a.k.a. Those Sods Across the Park, where Kim Philby — a former senior intelligence officer who’d been under heavy suspicion, since 1950, of spying for the U.S.S.R. — was still on the books as an asset. Some continued to believe, in the face of abundant evidence, that a man of Philby’s outstanding service and gentlemanly background couldn’t possibly be a Soviet mole.

Le Carré seems to have spent a lot of this time in a state of creative ferment. A compulsive, ferociously speedy writer, he was also a busy painter and draftsman, a trait he later passed on to the mole in Tinker Tailor. His air of inward agitation continued to gather after his commercial breakthrough, in 1963, and “it would take him a while,” in Sisman’s words, “to grasp that he could now afford almost anything he wanted.” One of the things he wanted was a way out of his marriage and, more generally, the buttoned-up manners he’d learned. A louche novelist named James Kennaway, whom he’d known since Oxford, seemed to suggest a freer approach to life. Kennaway preached sexual libertinage in the name of getting one’s writerly juices flowing, but changed his tune when his wife, Susan, embarked on an affair with le Carré. The resulting tangle led to an identity crisis, a divorce from Ann, and The Naïve and Sentimental Lover (1971), an undigested, spy-free self-satire that became le Carré’s one acknowledged flop.

A change comes over Sisman’s narrative when it reaches 1972, the year le Carré married his current wife, Jane Eustace, and settled down to the demanding work of turning out bestseller after bestseller. We’re told that Jane, a former publisher, accepted his need to have “impulsive, driven, short-lived affairs,” and that the secrecy and tension these involved “became a necessary drug for his writing.” Beyond that, Sisman declines to poke around, saying only that the marriage has been very happy, and the story rolls smoothly on toward the present by an increasingly familiar route: the 1979 BBC adaptation of Tinker Tailor, which made le Carré a household name in Britain; his long run of number ones on the U.S. bestseller lists in the Eighties; his feeling, which arrived with the end of the Cold War, that capitalism could do with a dose of glasnost; and his disgust at the Bush–Cheney Administration’s faith in torture and exemplary war. It isn’t hard to guess his views on David Cameron, the sleek Old Etonian political trimmer who led the Tories to victory in this year’s British election.

Sisman has interesting things to say about his subject’s working methods. Le Carré doesn’t block out his plots in advance, which means that Tinker Tailor’s intricate time scheme was worked up over three very different full drafts. (He advises novelists “to come into the story as late as possible; the later the reader joins the story, the more quickly he or she is drawn in.”) Borrowings from life get pinned down: the recurring character Toby Esterhase, for instance, a Hungarian émigré with a poor grasp of English idiom, was modeled after the publisher André Deutsch. There’s a rehearsed sheen, in the biography’s second half, to many of the showbiz and publishing anecdotes, but also a feeling that le Carré hasn’t fixed his own identity as thoroughly as he’d like. Even writing A Perfect Spy didn’t exorcise Ronnie, who died, still a rogue, in 1975, having recently seduced “a woman in Brussels” by impersonating his son. As a man who’s grown rich by peddling stories, and — as the British say — a shagger, the son seems to worry that he’s continued in the old man’s line.

It isn’t clear that a more ruthless audit of le Carré’s love life would add much to Sisman’s book, however — in part because, by the time the blinds come down, the novelist is becoming merely an accomplished producer of unusually well-written, unusually leftish blockbusters in which the authentic-sounding dinginess and bureaucratic squabbling of the earlier novels have less impact. Sisman provides some clues as to how this came about: from The Honourable Schoolboy (1977) onward, the novels were more research-driven, and le Carré’s inner ham inched toward the driver’s seat as he sought out colorful people to base characters on. Social change was another problem: in spite of his best efforts, he’s never quite mastered the evolving language and manners of Britain’s elite under Margaret Thatcher and beyond. The connection between inherited privilege and the upper reaches of the civil and security services, which fueled the social criticism in his early novels, has weakened in his lifetime, too. The likes of “Biffy” Dunderdale and “Sinbad” Sinclair — real names from the annals of British intelligence — would now work in banking or in commercial law.

In the Sixties and early Seventies, when such figures had more clout, le Carré was writing on a different level, and the best parts of Sisman’s biography detail the circumstances that gave The Spy and Tinker Tailor their lightning-in-a-bottle quality. On one level, he had an amazing knack for timing: Philby’s escape to Moscow in 1963 electrified the publication of The Spy, and the revelation that Sir Anthony Blunt, former surveyor of the Queen’s pictures, had been a Soviet agent added to the excitement over Smiley’s People (1979) and the Tinker Tailor miniseries. Le Carré saw the Wall go up in Berlin, and he hammered out The Spy’s closing chapters — which picture the opposed superpowers as monster trucks blindly crushing a small civilian car between them — during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Anguish over the state of his marriage, his lover, and his children’s future also fed the novel’s gloom, which still shapes the climate of feeling around the Cold War. His depictions of spies either as unromantic, morally dubious manipulators or as ineffectual fantasists proved to be indelible, too. (“You bastard,” a former colleague yelled at him years later.)

On a deeper level, the spy novel offered le Carré a versatile set of metaphors for the decomposing empire he grew up in. The secret agents in the early books are not the only ones who have to piece cover identities together from the historical debris that comes to hand. In Tinker Tailor, Smiley is an idealized character, but le Carré — fresh from his troubles with the Kennaways — put a negative version of himself into the portrait of the mole, someone who’s “less, far less, than the sum of his apparent qualities,” taking “here a piece, there a piece” from those around him, “and finally submerging this dependence beneath an artist’s arrogance.” It’s an extraordinary mixture of psychodrama and state-of-the-nation novel, and an entertainment built to last. Even Philby, writing from Moscow to Graham Greene in 1982, expressed admiration: le Carré was “good reading after all that James Bond nonsense,” he said, though his plots were “more complicated than anything within my own experience.” He owned all the books, he added, and — apart from The Honourable Schoolboy — “enjoyed them all.”