They got into our car at a stoplight. It was cold. We never lock the doors in back. There were two of them. At the apartment they terrorized us. It took all day, most of the night. There was beating and thrashing and scorn and damage and fear. Sounds I didn’t know could come out of us. Above all it was boring. In the sense that it was all actions and all bad; there is no life of the mind available amid beating and thrashing and scorn and damage and fear, no space at the back of oneself to go to and think anything else. Long stretches of boredom that fill up with something like thinking but there is nothing to think except what it is, what it is to be in this, and what it is to be in this is simply and utterly nothing but what it is, no volume around it, no beach, no reverie. At one point Washington raised his arms to me and blood ran down both arms to the floor. I watched it hit the tiles, it would have been something to think about, cleaning blood off tiles. Sometimes it’s better to just replace them. Eventually in fact that’s what we would do, replace the white ones. We kept the black ones, which were sort of speckled anyway. But “eventually” is not a concept of mind that exists amid beating and thrashing and scorn and damage and fear. Even when they had Washington dance in the red-hot shoes, I wasn’t imagining analogies, Snow White, I was soaked into Washington’s dread, it had no edge. That is what boredom is, the moment with no edge.

To survive you need an edge.

One of them seemed to have the name Grimaldi. I’m slipping, Grimaldi said every so often in a breaking-apart voice and the other guy would cross the room and stand close to him and murmur. Then they returned to what they’d been doing, breaking glass, making sandwiches, whatever it was. Washington had blacked out by this time, he didn’t hear it or see it. I was on the floor with little holes burned in me but otherwise okay, pretending my hands were still tied although they weren’t, watching for the edge.

I’m slipping is what I thought he was saying but I couldn’t quite hear, it might have been I’m leaking or I’m lingering. There it was, the edge. He sounds like one of the undead, I said to myself. Now, I don’t believe in the undead, I’m a scientist, but numbers of people do and it stands to reason that among them are those who claim they are the undead and on that account fear leaking, lingering, perhaps slipping. They are people snapped shut on themselves. Don’t fall asleep yet. Their voices seemed made of wood or blows falling on rotten wood. If I moved, he laid his lash onto me, the one called Grimaldi, it was a length of plastic skipping rope he wore draped around his neck, sandwich in the other hand. His colleague was looking through our tea cupboard, Grimaldi came over, they were grunting and flailing and Grimaldi with the end of his lash knocked a tin off the counter, Formosa oolong, it crashed to the floor, bounced. He cursed. Washington’s eyes flapped open like a soul on a clothesline.

How blue are Washington’s eyes and what a good thing it is. Like sudden oceans. Like the shadow at the back of each wave after the fresh collapse. Blue as blue lane lines on the bottom of a blue swimming pool. Blue as the Atlantic at 30,000 feet. Blue as a Chinese winter dawn, blue as an Ohio summer dusk, blue as crows in the sun. Blue as distance. Gatorade blue, Alice blue, salt-lick blue, satellite blue. Satellites aren’t blue. I go too far with analogies. Washington notes this from time to time. I’m a blurter, a leaper, a presumpter, I come forward, he goes back. Every couple has a score, don’t they, I mean an orchestral score. And the fact of him being somewhat inward and me as subtle as a cheap-motel sign gives our score a jumpy character. We met on a bus in northern Greece, Washington and I. A vacation tour. Everyone else on the bus was Chinese. I don’t recall why I took the Chinese tour and I never asked Washington why he did. Our guide was perplexed but valiant and translated all her monologues into shrill unusual English. Her name was Ling. I wondered idly where Ling got her English until the day, it was a long apathetic day of mountain switchbacks and hollow clouds leading to early dinner at an olive-oil factory managed by Ling’s cousin, when she unfurled the microphone and turned up the volume, already quite high, to favor us with the entire repertoire of Karen Carpenter. She smiled while she sang. All this sentimental material I could mention to our couples therapist the next time we met was flowing across the front of my mind while at the back I rummaged for anything I knew about the undead. Bad walkers? Brain eaters? What else? But now he was frowning at me. You have a problem, I said. Need to piss, said Grimaldi. I gestured with my forehead in a down-the-hall direction. Off he went, sidling and ducking. He forgot his lash.

I saw Washington notice this, the lash. I lay back on the floor in a posture of reflection. I was in physical pain. From the pain came anxiety crawling out all over the place. A hot-and-cold-at-once anxiety on little childhood currents, starting up everywhere in body and mind, tingling every follicle. The vagus nerve organizes such reactions. I was mentally following the path of the vagus nerve around my body and seeking to quiet it when a cry broke through my thought. From the direction of the bathroom. Grimaldi had met Rocket.

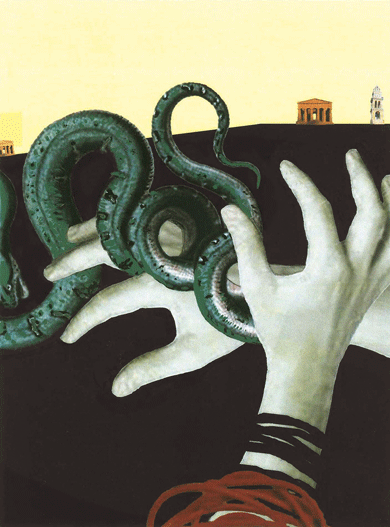

We keep Rocket in the bathroom. He likes to nest in a pile of towels and have easy access to the bathtub, filled. A python bathes most of the day when he isn’t sleeping or otherwise busy. Rocket has a calm and accepting nature generally but snakes don’t see very well and have no ear canals at all. They navigate chiefly by smell. So when a scent triggers the feeding response the next thing that moves is food. Perhaps Grimaldi ought not to have wandered into Rocket’s environment with a sandwich in one hand. They were in close communion when they toppled out of the bathroom. Grimaldi’s cries tore the air and a terrible smell came off him. Pythons subdue their prey by wrapping the upper torso of the victim and tightening the coils gradually. Constriction has as its main purpose the reshaping of the victim into a narrow oblong package fit for swallowing, preferably alive. Items up to the size of a small antelope can be dealt with in this way. Grimaldi was, as it happens, too big to be swallowed by Rocket but he did not know this and Rocket was proceeding with enthusiasm, hence Grimaldi’s repeated cries of Hack the thing! Hack it off me!

Meanwhile I was starting to focus in on the relationship between these two guys. The other still wearing his big KGB sunglasses. I remembered thinking he looks like Putin when he got into the car all those hours ago. Rescuing Grimaldi was evidently a low priority for Putin at this point. From where he sat on the La-Z-Boy he aimed a command across the room. Machine down, Grimaldi, machine down. His voice was like feces, if feces had a sound, if feces were a sound and I know what that sound would be from dreams I’ve had since then in which his bottom-of-the-shit-barrel voice is a dark soundtrack. At the same time, I’d noticed earlier, Putin had no smell. A sort of iridescence came out of him and stayed in the air.

The big KGB sunglasses turned in my direction. Get it off him. Well, ordinarily this would have been difficult because the way to deconstrict a python is to have Person A hold its head while Person B uncoils the coils one by one and loops them onto the floor. However, at the sound of the other guy’s voice Grimaldi’s entire body had gone limp and seemed to shrink so suddenly that Rocket lost his grip. The snake paused, then slid off across the floor and up the fire screen to the mantelpiece. Grimaldi lay silent and was jerking a bit. By now I was sure his relation to the other guy was that of personal slave, with Putin controlling his mind by keeping him drugged to the eyeballs, in the zombie tradition. Grimaldi had lost one shoe and one sock in the fracas with Rocket. He had a long white foot like a rabbit’s, covered all over the sole with weird little cuts, as if he had walked on ground glass or some very spiny thistles. I recognized standard zombie-enslaving procedure (or at least the theory of it that was current when I studied pharmacology some years ago): an abrasive residue like glass is mixed with Datura stramonium (plus extract of the puffer fish) and put in the shoe of the victim. The poison burns into the bloodstream through the abraded skin of the foot and stuns the poor bastard’s metabolism, sending his inner manikin screaming down to the back corner of his soul where it crouches and waits for orders. From the sole to the soul, as it were. Sorry, my puns aren’t much better than my analogies. Washington frequently notes this, too.

I gazed at the ceiling and considered S-O-U-L-S. The “soul of Greece” was a topic that often arose in conversations with elderly gentlemen in tavernas when Washington and I were on the Chinese tour. These gentlemen seemed to mean something glorious and transhistorical rather than the irregular lump of solid “it” that most of us have in mind. Washington’s soul I did not glimpse at all until the very end of our time in Greece. We had left the bus and traveled to Athens for our final two days. It was 42 degrees Celsius in Athens. We kept having small violent fights about small stupid things. If I describe them I will soon sound like a pressed piano key so I will merely mention that whenever Washington entered our hotel room he locked it behind him. Then closed and locked the windows. Then checked the closets. It wasn’t the sheer illogic of these actions (why check the closets after you’ve locked the door?) so much as their banality that bothered me. Big philosophical forms of dread are fun to discuss but tiny terrestrial terrors just make me depressed. And if I questioned him he’d say, I was brought up in New York City I have these fears, and give a sort of fake gangster laugh. So there we were, our last evening in Greece, not speaking, trailing around behind an English tour group in the new Akropolis Museum of Athens. It was wonderfully cool in the marble corridors of the Archaic Gallery. Everything seemed to float, in fragments, in its own vague light. Here are broken-off pieces of buttock or torso or shoulder, draperies streaming in midair, and many an empty pedestal with removed to the british museum inscribed quietly underneath. I was studying a shard of pottery on which someone in the seventh century b.c. had scratched a single name, over and over, the same name, and I was wondering whether a person would do that as a blessing or a curse — or maybe in hapless sorrow, like the postcard my mother once got from my brother when he was on the downslope to drugs and death. On the back of the card he’d written simply Michael Michael Michael, his own name, three times. Just then I heard the closing bell ring and I looked around, realizing I had quite lost track of Washington. I made my way to the main exit, couldn’t find him. Threaded back through the crowd to the Parthenon frieze, couldn’t find him. Dashed around the gift shop, nothing. Returned to the main exit and lingered there until firmly ejected by a guard.

Outside it was darkening. I walked toward Kolonaki Square and sat down on a stone bench. Men at small lighted kiosks were handing out gelato and ices all along the boulevard. The heat hung in shreds. I watched people drift past, talking busily, everyone in pairs or groups. Feeling ugly and sweaty and lonely and snubbed I closed my eyes. Flashes of accident, death, flying home with his coffin crossed my mind, and where had he put our passports? How much money was left? Who could I get to phone the airport? Should I call the police? Would they believe me? What’s the Greek word for “police”? I took off my glasses and was searching my pockets for something to clean them, all smudgy with heat and despair, when a person sat down on my bench.

Outside it was darkening. I walked toward Kolonaki Square and sat down on a stone bench. Men at small lighted kiosks were handing out gelato and ices all along the boulevard. The heat hung in shreds. I watched people drift past, talking busily, everyone in pairs or groups. Feeling ugly and sweaty and lonely and snubbed I closed my eyes. Flashes of accident, death, flying home with his coffin crossed my mind, and where had he put our passports? How much money was left? Who could I get to phone the airport? Should I call the police? Would they believe me? What’s the Greek word for “police”? I took off my glasses and was searching my pockets for something to clean them, all smudgy with heat and despair, when a person sat down on my bench.

He took my glasses from me and polished first one then the other lens with a handkerchief taken from his breast pocket. A familiar Washington-clean-linen smell rose around me, mingling with my own vapors. There comes a moment when you realize that other people are not interchangeable. I looked for you! I said and suddenly wept. He wept, too. Later that night he gave me the poem he’d composed in the café at the Akropolis Museum. He said it was a found poem and I said, Good I’m a found person. Using a red pencil he had circled all the past participles in the Akropolis official museum guide.

Adapted

Balanced

Blown up

Bombarded

Climbed

Contested

Converted

Demolished

Drilled

Encroached on

Excavated

Fortified

Hunted

Kept secret

Not planned

Occupied

Painted

Partly planned

Planned but never built

Polluted

Prohibited

Refurbished

Revered

Rock-cut

Sketched

Sold

Sprung fully armed

Tested superbly

To

be continued

I guess you can guess the title he gave it. It was I who alphabetized. The poem is framed now over our kitchen stove. But I digress.

Kiss me, Grimaldi. The voice ran hot across the room and into Grimaldi’s pooled limbs, organizing them instantly the way a coat hanger organizes a coat. Grimaldi scuttled over the floor and began pressing kisses to the toe of Putin’s boot, a dark-leather boot stitched with tiny mirrors, a voice that seemed to come from the boot. What is the kiss for, Grimaldi? and Grimaldi answered, To buy love. Putin: What are the mirrors for? Grimaldi: To bend evil. What are the scissors for? To cut me if I extend.

Now, I myself saw no scissors in evidence but neither was the kitchen floor covered in water, and so Putin’s next command — Walk in the water, Grimaldi — indicated a private slave code. Grimaldi got to his feet. He looked around wildly. He was very young, I hadn’t noticed this before. His eyes were holes in his head. But Grimaldi was not seeing in the outward direction, something had reversed the function, his eyes only registered what or who was looking at him. Shame eyes. Time to cha-cha, said Putin. Suddenly I was afraid. There was endgame in the air. How many kinds of kisses are there, Grimaldi? said Putin. Nine kinds, Grimaldi answered, for some reason whispering. Use number six. Grimaldi began to move.

Pity is a corrosive substance. I’ve learned to avoid it in my work (I work in a lab). I can’t love everyone, I can’t give back their prayers. As Grimaldi began to move he forgot that his one foot was bare and his traction unequal. The left foot slid fast on the floor and he stumbled forward. He stumbled heavily. He looked stupid. He looked like he knew he looked stupid. He looked like my brother. Pity came over me in a wave. There’s not much to know about my brother except that when he was alive we had a charged speechless relationship like a vacuum tube. To me (I was younger) his life always seemed to be falling apart — rented rooms, railroad bridges, skinny girls, dirty deals, everything betrayed him but it wasn’t his fault. It was never his fault. He’d come home after, betrayed and bloody, and we patched him up. My mother patched him up. I watched from the stairs. I hated watching but I couldn’t stop. His broken face, his whole surface throbbing with shame, annihilated me.

When Grimaldi stumbled and his shame eyes swallowed the room in all directions, my hands reached out to him. What was I thinking? My brother and I never embraced, kissed, hugged, we weren’t that kind of family, except the day, I recall a rainy Saturday, that he stood before me in the kitchen in tears because his girlfriend was knocked up and needed cash. I was important that day. I pitied him and gave him cash. Those were the deepest feelings we got to. Years later when he died drunk in a bathroom in Europe I realized I had had no real interest in or compassion for him, just this weird sibling dissolve at the edge where my personality met his, this smudging of two selves into one. A dark form shimmered past my visual field on the left.

Rocket was on the move, too. I could see the snake’s tongue flicking in and out. Snakes, as I’ve said, learn the world by smelling — that is, through the tongue, which is covered with sensory corpuscles that are able to carry the slightest trace of information back to the palate and thence to the brain. But Rocket had descended the mantelpiece and paused, he needed more data. By laying his lower jaw on the floor and picking up ground-borne vibrations he could chart his course precisely. He was charting for Putin, who had been standing by the door to the balcony, was now stepping out onto the balcony, humming to himself and doing a bit of cha-cha, a little this way, a little that, lightly absorbed in his own trance, his body moving like a scarf dropped through air onto water and turning with the current, coolly turning. He was a beautiful dancer. Rocket was up his leg, across the torso, and wrapping his neck before you could say stand-up comedian. Putin cha-cha-ed no more that day.

Grimaldi had subsided to the floor, confused. I think his body confused him. Air confused him. From his body and from the air was suddenly absent the entire hot horrible pressure of the other guy. Did he connect Putin’s fallen form on the balcony with this absence? He turned over and lay on his back, making small sounds that were (to me) like a broom sweeping the stairs, this calm sound. When my brother died I swept the porch and the stairs all afternoon. Something about sweeping and death, they go together. And there went Rocket gliding past in the other direction. He had an expressive look. People assume reptiles lack moral sense but that is because we make no close observation of their decisions. Rocket has a keen appreciation of the ruthlessness of men but on those rare occasions when ruthlessness abates he is moved to wonder and sympathy. He was sliding along Grimaldi’s leg and up over his T-shirt into the V-shaped hollow formed by his bent arm. Here he coiled himself carefully and paused, laying his head on the edge of Grimaldi’s chest with a small sigh. Grimaldi raised his head to look dazedly at the python. Snake likes me, he shyly shone. Then as a moonlit road he dimmed again and ghosts blew across him.

I’ve always thought random homonyms startling. Words that sound alike but mean differently, like sole, “bottom of the foot,” and soul, “principle of life, thought or spirit.” Linguists tell us that, given the great number of meanings we want to express in our language and the limited number of sounds we can produce with our mouths, there’s nothing startling here at all. Homonyms are inevitable. Still, perhaps you share with me a compulsion to find some primordial link between, on the one hand, being able to walk along the world on little platforms of tough flesh and, on the other hand, having a conscious, sensible, or spiritual otherness aloft within your body. A primordial link between the sole and the soul is of course etymologically bogus. The two words have separate historical formations (sole of the foot derives from Latin solea, “shoe or sandal,” while the origins of soul as spiritual essence are quite unknown). Any overlap in sound is, scientifically speaking, a total accident.

And yet, and yet. Don’t they overlap in other ways? What comes to mind are considerations of tenderness or vulnerability — where is pain felt as sharply as in the bottom of the foot if not in the spirit? Then too there’s a spatial aspect. The OED defines sole as “the lower part, bottom, or under surface of anything” — from a plow to a rudder to a drainpipe to a furrow to a glacier — and don’t most people think of their S-O-U-L as a deep-down layer, a metaphysical substrate? In any case, the reason I mention all this is that, as I pondered the python curled in the crook of Grimaldi’s arm with his smooth snaky belly exposed, I found myself staring at the perfect little soles of Rocket’s feet. You almost certainly know that snakes once had feet, attached to legs, which they shed — for shame according to the Book of Genesis, for mobility according to theories of natural selection. Legless, a snake can travel as fast as a human, climb trees, navigate almost any horizontal trajectory, and swim more gracefully than a fish. The python does retain vestigial traces of hind legs, those two tiny protuberances on the underbelly that poke up like the soles of forgotten feet. Every time I noticed them I felt strange; a wind rushed by. Is there such a thing as evolutionary pathos? Two bumps of bone evoking a 130-million-year-ago hesitation in whatever random process or brooding intelligence was nudging creation along at the time. Snakes also carry inside them the remains of a pelvis. Does this make it uncomfortable to grind along the floor on your belly? But snakes don’t feel pain the way we do, do they? Snakes have this in common with zombies, or so I have heard, although my real opinion is that, even from our lofty place on the ladder of being, we don’t really know what snakes feel or zombies think. We don’t know who has a soul and who doesn’t. There’s no test for soul. You may be familiar with the story of Dr. Duncan MacDougall, who in 1901 attempted to discover the weight of the S-O-U-L by calculating the mass lost by a human body at the moment of death. His experiments gave him an average result of twenty-one grams but these could never be replicated by anyone else and are regarded as scientifically meaningless. More recently an Oregon rancher tried a similar experiment on eight sheep, three lambs, and a goat, who all gained weight at death. He continues to puzzle over this result.

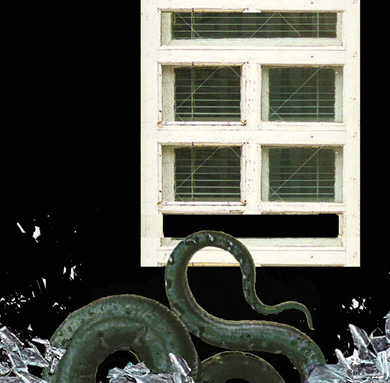

Scientists in general regard the soul test as a futile research. I’m not so sure. I think there are clues. I don’t mean some bluebird that flies through the room and keeps going and ends up in heaven. On the other hand, why was that window open?

So finally this long day and night come to an end. Hours later. We are sitting at the kitchen table. Washington has the lash in his hands, vaguely unfolding and refolding it around its plastic handles. A cold dirty yellow dawn has strayed in. On the other side of the table is a sort of pile of Grimaldi, adrift in his hoodie, face absent. When the police arrive they will remove Putin’s body and take Grimaldi into custody. He seems quiescent. I try questioning him. He looks at me, his eyes burn across the air, the air falls apart, he makes his broom-sweeping-the-stairs sound, possibly a laugh.

I hate this laugh.

I hate sitting here. Grimaldi sinks back down into his hoodie. Well then, I say. Something needs to happen, I don’t know what. Screaming? Sobbing? Laceration? A thunderstorm? Some kind of exchange between me and this blind beaten person. Some documentary-style explanation — They tied my foot to a pole at night, they told me they could put me in a bottle anytime they liked? Or perhaps a moment of redemption (we all light sparklers and go out to the balcony, stand side by side gazing out on the dawn)? Then again why not just have Rocket murder him.

But Rocket has made his own decision. When the police officer bustles in and out of the bathroom to take a piss right beside his head, Rocket does not even wake up.