Discussed in this essay:

The Lost Time Accidents, by John Wray. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 512 pages. $27.

Waldemar “Waldy” Tolliver has been exiled from time, trapped at 8:47 “this” Monday morning in the library of a Harlem apartment that was once inhabited by his two maiden aunts. He has an armchair, a table, half a bottle of beer, paper, and a refillable tortoiseshell pen. Around him are piles of junk: newspapers, Game Boys, carburetors, assault rifles, and “chronometers of every make and model, pendulums primed, springs oiled and wound, circuitry buzzing.” The book Waldy is writing, a history of his family and its fatal fixation on time, will turn out to have been John Wray’s new novel. At least initially, it looks like an energetic postmodern romp in the manner of recent books by David Mitchell, Ned Beauman, Jonathan Lethem, etc. It straddles the twentieth century (and our stub of the twenty-first), features a large cast, and plays with the conventions of genre fiction and the fuzzy line between genre and highbrow. “I’ll have to treat my duration as a mystery and a sci-fi potboiler combined,” Waldy announces, before going on to treat it as a historical and epistolary novel too.

In June 1903, Waldy’s great-grandfather, a pickle magnate named Ottokar Toula from the town of Znojmo, in Moravia, is run over and killed by a watch salesman. Ottokar had been engaged in “a series of experimental inquiries into the physical nature of time,” and when he arrives at the hospital after the crash a cryptic note addressed to his mistress is found in his pocket. Some of it seems to be in an alliterative code — “Bears boors & bohemians bedevil these lateral labors” — and it includes suggestive phrases: “Time can be measured only in its passing”; “Backwards time is impossible, forwards time is absurd.” Ottokar’s descendants, beginning with his two sons, Kaspar and Waldemar — the narrator’s namesake — become obsessed with figuring out what the note means, what Ottokar was after, and whether or not he found it. The brothers go to university in Vienna, where Waldemar gets absorbed in the hermetic world of chronology and becomes a recluse. Eventually, he thinks he’s grasped what his father was driving at, that time moves in circles, “chronospheres,” not straight lines, but before he gets the chance to publicize his discovery, Einstein comes out with the special theory of relativity, which invalidates it. Einstein’s triumph confirms Waldemar in his already pungent anti-Semitism. His research curdles into the conclusion that time is a Jewish conspiracy. He joins the Nazis, becomes a notorious interrogator in the Gestapo, and ends up a Josef Mengele–like mad scientist at a concentration camp, where he performs ghastly experiments on the inmates in the attempt to prove his theories. Kaspar, on the other hand, falls in love with Sonja, the daughter of a Jewish physics professor. They produce twin girls, whom they name Gentian and Enzian. When the Nazis come to power, Kaspar’s family escapes to Buffalo, New York, and changes its name to Tolliver. Sonja dies en route, but Kaspar builds a successful watchmaking business with her cousin, marries again, and has a son called Orson, the narrator’s father.

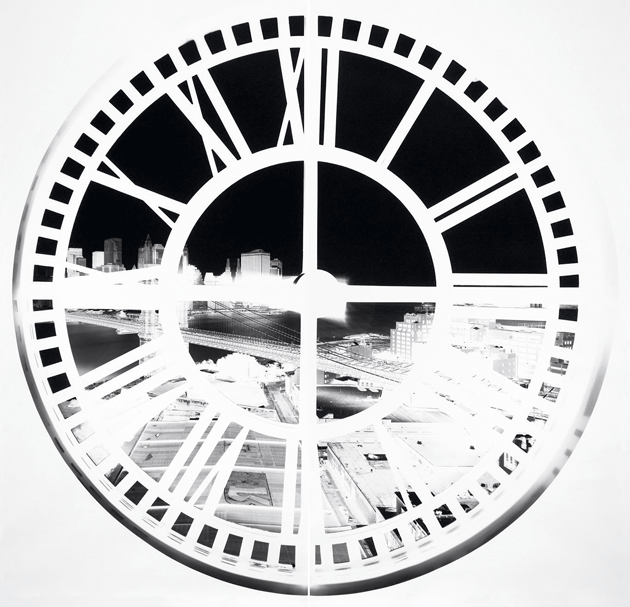

“Clock Tower, Brooklyn, XLIV: June 22–23, 2009,” a photograph by Vera Lutter. Courtesy the artist and Alfonso Artiaco, Naples, Italy

Waldemar vanished from the camp at the end of the war. The disappearance burdened his family with the possibility that he may have been onto something — that he managed, perhaps, to escape justice by dislodging himself from the flow of time. Enzian and Gentian are strict Jews and read the Talmud to each other at bedtime, but they are sure that Waldemar has figured something out: Enzie studies physics at college, though she continues to refuse to speak the name of Einstein, whom she believes robbed her family of its place in the history books; Genny sets about curating an “archive” of objects relating to time — more or less everything, hence the piles of junk — in their apartment. Orson becomes a writer of sci-fi erotica as well as the author of The Excuse, a novel about the future that becomes popular in Age of Aquarius America — and a bestseller when some of the predictions it makes turn out to have been correct. It becomes the holy book of the United Church of Synchronology, a religious organization that reveres Orson as a prophet. Waldy, Orson’s son, has an affair with the wife of the church’s “First Listener” (a sort of cross between CEO and high priest) in the course of his own temporal investigations. Wray splices the story of their relationship with the story of the rest of Waldy’s family: where the two stories collide, the novel peaks, and the family’s secret — the secret behind their secret — is revealed.

Waldy’s vocabulary is thick with his family’s preoccupations even when he isn’t thinking about time. “You were trapped inside a Möbius loop of admirers” is how he describes his first encounter with the woman who will become his lover. Characters he meets seem equally obsessed: an old man at the nursing home where he works has memorized the average life span of everything from a rainbow trout to a football. Like the aunts’ apartment, Wray’s novel is stuffed with souvenirs of the past century. Scenes play out against a whirl of political moments, scientific and artistic breakthroughs, and wars. In Vienna, a salon hosted by Wittgenstein’s dad buzzes with word of Einstein’s latest theory. Sonja is a foulmouthed revolutionary Communist who models for Klimt.

In New York, Waldy’s aunts become a fixture of 1960s hipsterdom, known for their extravagant dinner parties at which they play host to the likes of Eldridge Cleaver, Harry Smith, Carl Van Vechten, William F. Buckley Jr., Charles Mingus, and Buckminster Fuller. One of their guests is Joan Didion, whom Wray cheekily ventriloquizes:

It’s a pretty nice evening and not much is happening so someone suggests that we go see the Sisters. Not having any idea who the Sisters might be, I wonder aloud whether they won’t object — it’s past ten o’clock on a Wednesday — but LaMont waves my question aside. “They’re having one of their nights,” he says, as if that explains things.

At the end of The Excuse, Orson writes that “our consciousness is all the time machine we need,” a slogan that finds its way onto hippies’ T-shirts. Wray has fun with the notion, constantly probing the relationship between time and mind. Kaspar tells his brother that when he has sex with Sonja he feels as though time stands still. Waldemar misunderstands him and tries to borrow Sonja so that she can stop time for him too. Wray reminds us that we often think about our lives using the language of time travel, projecting ourselves into possible futures, posing what-ifs about the past. “What are you going to do, Mr. Tolliver?” the nursing-home guy asks the narrator. “Go back in time and kill your father’s uncle?” In a sense, that’s exactly what he intends.

Reading can transport the imagination back or forward in time; it can also accelerate our experience of time or slow it down, as Waldy discovers when holed up in an attic with almost nothing to read but The Official World of Warcraft Game Guide. Wray himself pulls off a fiddly piece of time wizardry by telling Waldy’s story alongside his family’s. The family story covers a hundred-odd years, Waldy’s barely thirty, but both take up about the same amount of space on the page, obliging the reader to experience narrative time at two velocities. Physical and literary time are conflated most dramatically in Enzie and Genny’s apartment, which Waldy realizes is a massive time machine. Waldy sits down in the middle of the apartment and starts to write; by giving him the space in which to do so, the machine fulfills its function.

The Lost Time Accidents revisits the historical period in which Wray set his first novel, The Right Hand of Sleep (2001). That book tells the story of an Austrian man’s return to the village of his childhood after becoming a deserter during the First World War and spending years of semi-slavery on a Ukrainian collective farm. The Anschluss happens some way in, as it does in The Lost Time Accidents, but the style and tone of the two novels are different. The Right Hand of Sleep is a somewhat dutiful realist novel that was, on its release, flatteringly compared to Joseph Roth. It opens in October 1917 and shuffles toward the outbreak of the Second World War and a denouement that most readers will have seen coming from about page fifty. The Lost Time Accidents, by contrast, is frantically paced and unpredictable, and instills the reader with a sense of urgency from the get-go — about Ottokar and Waldemar’s “breakthrough,” and then about Waldy’s confrontation with his diabolical ancestor. This is the first sentence of The Right Hand of Sleep: “A boy came out of the house first, the crumbling, sun-yellowed house with the dark tiles and ivied sides, the peaked roof and sandstone steps down which he went stiffly, nervously, adjusting the plaid schoolboy’s backpack on his shoulders.” Here’s the opening of The Lost Time Accidents: “Dear Mrs. Haven — This morning, at 08:47 EST, I woke up to find myself excused from time.” The former leaves nothing to chance; the latter, in far fewer syllables, introduces a set of mysteries and stakes its success on their resolution.

Wray has declared himself untroubled by his lack of a consistent authorial voice: “I’m not a big adherent of the ‘find your voice’ school,” he admitted in an interview shortly after the publication of his third novel, Lowboy (2009). “I don’t actually believe that we’re all somehow born with some voice that’s inherently ours.” He has also spoken of his admiration for film directors such as Stanley Kubrick and Billy Wilder, who could “go from directing a thriller to a period piece to a romantic comedy without missing a step” — and said he had set out to imitate their versatility. Canaan’s Tongue (2005), Wray’s second novel and another period piece, switched the dappled nostalgia of Old Europa for the heat of the American South in the nineteenth century, and the cast of Mitteleuropeans for a vibrant jangle of Southern dialects — Twain looms large as an influence, as does Poe. With Lowboy, Wray reinvented himself again, as both a thriller writer and a visionary surrealist. The novel follows a paranoid schizophrenic teenager, who has escaped from a hospital, as he travels around New York on the subway. He has stopped taking his medication, and Wray’s prose mirrors his increasing mental disorder. At the novel’s climax, the escapee, Will, tells his girlfriend about a florid psychotic episode he experienced. The text here is doubly mad — a mentally ill man’s account of the most extreme phase of his illness — and Burroughsian in its mix of body horror and narcotized syntax:

Every day the world got flatter like a pancake or a candle on the dashboard of a car. Everything in the world was made of paper. I woke up one night with paper in my mouth and paper stretched across the room and light blue paper on me like a dress. . . . The ceiling came and brushed against my face it wasn’t painful but it was difficult to watch. Things kept on moving. The nurses for example. But how did they keep from sliding into each other . . . how did they keep from tearing themselves up.

For all Wray’s stylistic side-switching, his books share a certain kind of protagonist: one who is in some way out of step with his society, and whose alienation affords him a privileged perspective on the events of the story. Wray — who has been in his time a cab driver, groundskeeper, tutor, and rock musician, and who dropped out of two creative-writing programs — appears to feel a kinship with the anomic. Thaddeus Morelle, the Southern outlaw at the center of Canaan’s Tongue, is a moral relativist, a skeptic contemptuous of the faith and optimism of his countrymen, which he exploits for his own ends: “This nation was founded on belief — credulity pure and simple. . . . Without an understanding of belief — without a sympathy for it, a talent for it — you will never make your penny.” In The Right Hand of Sleep, Oskar Voxlauer is granted a more rounded view of his country’s political situation because his life has liberated him from ideology. His time as a soldier in the First World War led him to ditch his father’s kaiserism; his subsequent zeal for Communism is lost when he is sent to a labor camp along with his girlfriend, who has been charged with being a kulak; and his absence from Austria means that he can see Nazism for the pathology it is. In Lowboy, Will’s condition leads him to believe that the earth is getting hotter and that, as a result, the world is going to end. He is, of course, absolutely right: it’s our complacency that’s peculiar. In each of Wray’s novels, the central character’s outsider status colors the language of the book and sets up its central drama: Will’s condition imbues the writing with visionary weirdness, whereas Waldy’s exclusion from time enables him to produce the novel we’re reading and to face up to the other Waldemar.

Wray draws discreet connections between The Lost Time Accidents and The Right Hand of Sleep. For one thing, he gives a minor character in The Lost Time Accidents the name Ryslavy, which is also the name of a Jewish barkeeper in The Right Hand of Sleep who is forced out of his home by the Nazis. In both books, the Nazis’ sanctioning of anti-Semitism poisons communities, turning former friends and family members against one another. Villagers who have been drinking happily at Ryslavy’s for years suddenly begin to suspect him of all kinds of underhandedness. Waldemar’s anti-Semitism commits him to disowning his brother after his marriage to Sonja. Though Ottokar is a Christian, Wray casts doubt on the Teutonicity of his heritage, describing his beard as one that “demands to be described as Talmudic” and underscoring the absurdity of ethnic segregation in a community that is so intermixed.

The two books, however, characterize their Nazis very differently. Kurt, the most prominent Nazi in The Right Hand of Sleep, is hardly sympathetic, but Wray takes care to explain how he turned out the way he did. He lived with an abusive, alcoholic uncle, and he gets a long flashback sequence in which he describes his daring escape from the scene of Chancellor Dollfuss’s assassination, followed by his lonely rise through the party. His longing for a father figure is met by his superiors, including Himmler, who possesses a look of “schoolteacherly attentiveness.” The older Waldemar, on the other hand, from the moment of his father’s death, is monstrous, a caricature, a loon. His nickname, the Black Timekeeper of Czas, elicits a pulp-fiction frisson. He believes that “sequential time is a convenient fiction, an item of propaganda — a fable propagated from the birth of Jesus outward by a collective of interests.” He means the Jews, who are now “approximately one thousand, nine hundred and five times more powerful than they were at the beginning of the so-called Christian Era.” When Waldy finally gets to confront him, he finds the Black Timekeeper to be unrepentant, still inclined to view humans as “test subjects.” Waldemar the narrator may be the first of his family with enough distance between himself and his ancestors’ crimes to be able to reckon with them, but he is still unable to comprehend the Black Timekeeper as fully human. This isn’t a failing of the novel, it’s a failing that Waldy shares with all of us who find it difficult to square the actions of Waldemar and Mengele with their humanity. Like us, Waldy can only comprehend them as monstrous.

Fredric Jameson recently wrote in the London Review of Books that the time-travel narrative is “pre-eminently suitable for its use in ideological interpellation.” A time-travel scenario, he suggests, allows an author to situate different historical (and future-historical) periods alongside one another, making plain the advantages and disadvantages of both — a utopian past versus a dystopian present, or a dystopian present versus a utopian future. Wray has no discernible ideological agenda, but his characters do. The myth of their family’s ability to time travel — or to crack the riddle of Ottokar’s note — is a protective screen, a way of papering over Waldemar’s appalling crimes. Enzie and Genny bury themselves in their experiments and their archive; Orson escapes into his novels, and then into the self-delusory pseudo-pomp of his position as head of the Church of Synchronology. It’s up to Waldy to journey into the past and “close the circle.” In its final quarter, The Lost Time Accidents begins to feel more somber, less romplike. It becomes a book about guilt and about storytelling as a means to obscure and address that guilt.