Staging — the practice of deliberately arranging a scene — has coexisted with documentary photography from the beginning. When Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre published a seminal tract on a method for fixing images onto a shiny piece of silver-coated copper, in 1839, he also described the relatively recent art of the diorama. Photography and staging, you might say, were launched into the world as twins.

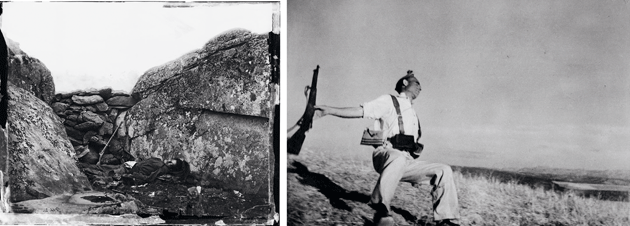

Nineteenth-century portrait photographers readily took to fakery, often posing their subjects in tableaux that were designed to evoke classical or religious motifs. From portraiture, staging spread to war photography. In the years leading up to the American Civil War, Mathew Brady rented ornate studios in New York and Washington to stage portraits. His associates, Timothy O’Sullivan and Alexander Gardner, were accustomed to posing Washington’s bon chic, bon genre amid fringed and Gothic chairs, a Corinthian column, a gold clock whose hands rarely moved, and a leather-bound tome. When they went on to photograph the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, in July 1863, the pair saw little difference between moving a dead sharpshooter from his redoubt to a better setting nearby and posing a model in the studio. During the Spanish Civil War, seven decades later, Robert Capa probably had a Republican militiaman fake his own death for a photograph. These interventions did not diminish the ability of the images to communicate the gruesomeness of war, but no one pretends that’s all there is to say on the matter.

“A Homestead on Submarginal and Overgrazed Land. Pennington County, South Dakota,” 1936, by Arthur Rothstein. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

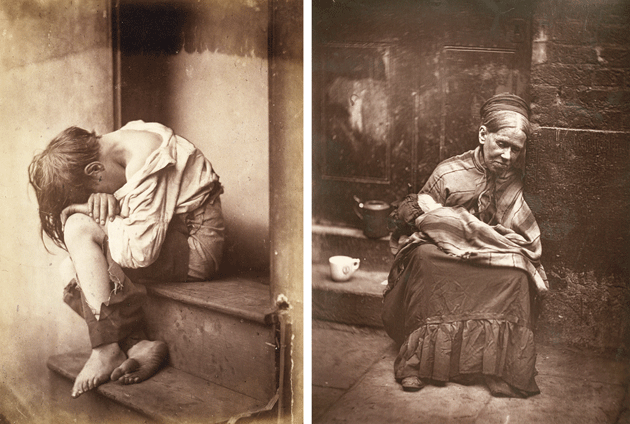

One obvious danger is the ease with which the origins of a staged image, or an artist’s intentions, can be forgotten over time. Consider Oscar Gustav Rejlander’s portrait “Homeless” (circa 1860), which shows a boy in rags sitting on some steps with his head bowed, and John Thomson’s “The ‘Crawlers’ ” (1877), which depicts a destitute woman in a crumpled dress. The photographs were both taken in London and are similar in mood, and if you did not know anything else about them you might never guess that while the latter wasn’t, as far as we know, photographed indoors, the former was staged with a model in a studio. Time readily erases the difference.

The same elision happens even with photographs that are now widely known to have been staged. In 1936, Arthur Rothstein, a twenty-year-old photographer, visited Pennington County, South Dakota. Rothstein, who worked for Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Resettlement Administration, was looking for a way to demonstrate the seriousness of the conditions that led to the Dust Bowl. While walking along a dried-up alkali flat, he found a bleached steer’s skull. He moved it onto a patch of cracked mud, photographed it, and later used the skull as a prop in several other scenes. One of the resulting pictures, published in the Washington Post, among other places, met with much acclaim before Rothstein’s staging was discovered. Political opponents of the New Deal used the opportunity to paint Roosevelt’s efforts to ameliorate poverty as deceitful. Other photographers suffered similar controversies. Walker Evans has drawn posthumous scrutiny for adding an alarm clock to a tenant farmer’s mantelpiece, whereas Edward Curtis took flak during his lifetime for removing alarm clocks, along with every other modern device, from his portraits of Native Americans.

From left to right: “The Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg,” 1863, by Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; “Death of a Loyalist Militiaman,” 1936 © Robert Capa/International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos

In the years after World War II, Life magazine hired Robert Doisneau to photograph a story about lovers in Paris. The apparent aim was to portray the city as quaint and romantic, to play to the nostalgia of servicemen returning from the fighting in Europe. Doisneau used actors to stage the photo essay, and while it’s unclear whether he intended to hide what he had done to set up his scenes, the decision came back to bite him forty years later when two people who claimed to be the loving couple at the center of “Le baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville” sued, unsuccessfully, for a cut of the royalties.

From left to right: “Homeless,” circa 1860, by Oscar Gustav Rejlander, courtesy George Eastman Museum; “The ‘Crawlers,’ ” 1877, by John Thomson, courtesy London School of Economics Library

In 1999, Werner Herzog, the film director, made his so-called Minnesota Declaration, in which he explicitly embraced staging:

There are deeper strata of truth in cinema, and there is such a thing as poetic, ecstatic truth. It is mysterious and elusive, and can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.

His view echoes that of John Ruskin, the nineteenth-century artist and critic, who defended J.M.W. Turner’s impressionist paintings as representations of “moral truth” over “material truth.” Since 1936 at least, documentary photographers have struggled to find acceptance for ecstatic or moral truth. The public, meanwhile, has simply expected truth.

“To manipulate an image is to lie”: for Patrick Baz, a French photojournalist and a juror for the 2015 World Press Photo competition, the equation was clear enough. In an essay for Le Nouvel Observateur last year, Baz explained why a fifth of the photographs that had made it to the penultimate round of the contest were disqualified. He was talking not about staging but, of course, about Photoshop. Many of the offending images had been altered to remove inanimate objects, a miscellany that included a garden hose, cigarette butts, electrical wires, and skin imperfections. In other pictures, day had been turned into night, buildings had disappeared into thin air, and captions had presented inaccurate information. As further controversy emerged, the news-photography industry closed ranks in opposition to post-processing and manipulation of any sort.

Top: “Raising a Flag over the Reichstag,” 1945 © Yevgeny Khaldei/Corbis. Bottom: John Filo’s original photograph of the Kent State protest © John Filo/Getty Images (left), and the altered version as it appeared in the November 6, 1972, edition of Time (right)

But manipulation is almost a necessary adjunct to digital photography. Digital cameras record images using millions of sensors that are laid out like a Roman mosaic. To create the appearance of a seamless whole, a camera must interpolate — i.e., guess — the missing information it needs from the surrounding pixels. The lower the camera’s resolution, the more interpolation is required to paint a digital photograph.

Two of the primary reference points for news photographers are the codes of ethics supplied by the Society of Professional Journalists and the International Federation of Journalists. The latter states clearly: “Respect for truth and for the right of the public to truth is the first duty of the journalist.” If that’s too vague, Santiago Lyon, the director of photography at the Associated Press, has a clearer standard: “The bright red line is the addition or subtraction of elements of a picture.” Four years ago, the Associated Press erased all the pictures of one contract photographer from its archives. The crime: removing a shadow — his own — from a sports picture.

Part of the problem is that “photojournalism” and “documentary” are often used interchangeably, when the former is really a subdiscipline of the latter. Much of contemporary documentary photography lies somewhere between journalism and art. Like Herzog, I find the insistence on an objective truth a bit too literal. Couldn’t documentary photography concern itself with a different ideal than absolute fidelity, something akin to what Seamus Heaney called the act of “undeceiving the world”?

While the ethics that govern photojournalism differ from those applied to other forms of image-making, the ethics of deception are, I think, constant. Any form of undeclared and intentional falsifying of a photograph (or a painting, for that matter) is lying. But what does actual deception look like? Two well-known historical examples of manipulating photographs both involve the addition of smoke plumes. The first, Yevgeny Khaldei’s “Raising a Flag over the Reichstag,” depended on both staging and manipulation. The Soviet Army claimed the Reichstag, in Berlin, late at night on April 30, 1945, when it was too dark to take a picture. To remedy this difficulty, Khaldei staged a flag-raising two days later. In the darkroom, he added plumes of smoke, borrowed from a separate negative, for dramatic effect. Later, under official orders, he removed one of two wristwatches visible on the arm of a soldier in the photograph. (The authorities wanted to avoid the suggestion that the soldier might have been looting.) There were truths there — the time the Reichstag fell, the state of Berlin, the evidence of possible looting — that Khaldei was obscuring.

The second example is the Lebanese photographer Adnan Hajj, a freelancer who worked for Reuters. In 2006, he doctored an image of Beirut, adding smoke to the skyline. After Hajj uploaded a second doctored image, which showed an Israeli F-16 fighter firing flares, Reuters removed every one of his pictures from its digital archive.

People’s sensitivities have changed since the early 1970s, when a technician blithely removed a distracting fence post from an image that showed the killing of a student at Kent State University. Today, manipulation of news images is taken seriously, and appropriately so. As Maria Mann, the director of international relations at the European Pressphoto Agency, told me, “People are tired of being lied to.” At the same time, she said, the volume of content being sent to news agencies, and the downsizing of editorial support for photographers, “works in the favor of those who want to deceive.”

So where are we left when it comes to staging and manipulation? For documentary photography that is not photojournalism, the standards are a bit more progressive. They allow for works such as Jeff Wall’s enigmatic staged photograph “Men waiting” (2006). Wall, who refers to his work as “near documentary,” has been open about his method. To create “Men waiting,” he cast unemployed Vancouver men, drove them to the location — a street corner in the eastern part of the city — and told them how to pose. That kind of transparency is what’s needed for any documentary photography that involves staging.

Top to bottom: “Videogame,” 2009, by Ana Casas Broda, courtesy the artist; “Men waiting,” 2006, by Jeff Wall, courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York City; photograph at the Royal Naval College, Helder, The Netherlands © Paolo Verzone/Agence VU

The self-representation of motherhood is the subject of Kinderwunsch, a series that Ana Casas Broda published in a 2013 book. (Kinderwunsch means “desire to have children.”) Casas Broda’s photographs are intimate staged portraits in which she engages visually with the experience of losing ownership and control of her body at a time when her children’s needs, at every turn, reigned supreme. In the book, Casas Broda describes her staging as collaborative, a time for the family to connect: “We play, they come up with ideas. We put together a scenario and they do whatever they want.” In one revealing “half-staged” photograph from 2009, her seven-year-old son, Martín, sits in the foreground, at home in Mexico City, holding a PlayStation controller. Concentrating fully on a game of Sonic Riders, Martín seems to be oblivious of his mother, who lies naked and asleep on the couch behind him. In the photograph he appears unaware of the sacrifices she has made to bring him into the world.

As it happens, the World Press Photo rules already make an exception for staging, at least when it comes to portraiture. Last year, after Paolo Verzone won an award for his staged portraits from Europe’s military academies, he called his discipline “the last secret playground, because you are free from constraints.” One photograph shows a Spanish cadet posed in an auditorium; another, a cadet in front of some painted torpedoes. Both images formed part of the prize portfolio. “The staging is part of the accepted process,” Verzone said, “not only by the industry but because all the portraits in the history of mankind have been staged.” For Verzone, military cadets make perfect subjects: they don’t fidget and are used to being told where to stand. “It’s the beauty of the portrait to be staged. There’s so much to invent in the photographic portrait.”

Members of the Grigioverdi del Carso association dressed as Italian soldiers during a World War I reenactment © Alex Majoli/Magnum Photos

For a recent project about the centenary of World War I, Alex Majoli, an Italian photographer, re-created battle scenes in the Italian Alps with a cast of actors. To my eye, the photographs look more real than the few images of fighting above the snow line that survive in German and Italian archives. In Europe, the practice of staging continues to evolve, notably in the work of Marta Soul, Jill Quigley, and Alison Jackson.

What, then, of “truth”? Last year, I put that question to Oliva María Rubio, the artistic director of La Fábrica and an art historian trained at the Autonomous University of Madrid, who has studied the Robert Capa photograph and others like it. “The history of photography has already shown that photography can lie,” she said. “The idea that photography is the truth or the sole basis of reality has been surpassed. Reality is what we construct for ourselves.” If partitioned from factual reporting, documentary can become a means of taking us beyond the type of images or stories that we are accustomed to seeing. An alternative reality, perhaps, albeit one that seeks to undeceive our own.

“But where do the boundaries of documentary lie?” I asked.

She laughed. “I didn’t say there were any.”