On my way home today I saw someone in the field, someone I once knew. I was coming down the road from a hill and saw him from a distance. Yet I knew it was him, even from afar and after so long. It was as though he had always been there, still as a tree. Kostya, with the weight of an old grief on his shoulders.

I headed down. He made his way across the field. And then he was there, in front of me, older now, with gray in his hair, but the same to me.

“Misha,” he said. “Hello. Can I walk with you?”

I was trying to recall the last time I had seen him or heard his voice. How long it had been. He had spoken to me in Russian. I wondered what he had been doing out here. It was quickly growing dark. And cold. He seemed tired but restless. There was no one else, not in the field or on the road.

So we walked. Kostya fell into step with me. I followed the road, passing under the old linden trees that we used to ride under with a bicycle, me on the seat and Kostya pedaling.

If he noticed me looking at him he didn’t seem to mind. He placed his hands in his jacket pockets. It was a hunting jacket that was too large for him.

“You still have that bag,” Kostya said.

I lifted the bag I was carrying. It was a leather tool bag that had been my grandfather’s. He had bought it from a tinker the day he was released from the camp, not knowing what it was for. He just wanted something of his own, he said.

I used it every day. I packed my lunch and a book. If it was light outside, I walked home reading, something I knew I should never do but did.

A motorbike almost hit me once. I felt the rush of air and the whisper of the motorcyclist’s arm as I tumbled into the field. As the engine noise faded, I saw the dim shape of a plane fly above me and thought of Kostya. It was the last time, I realized now, that I had thought of him.

“Here,” I said. “You can carry it for me.”

Kostya laughed. Still the same laugh. It was nice to hear it. He took the bag from me and we continued down the road through the fields.

The evening came. We smelled the cattle farm. We had been told that winter was coming earlier this year, but there was no wind tonight and the sky was open, full of stars.

“I was heading to the railway,” Kostya said. “When I saw you. I was heading to the mill.”

We called it the mill because it was once a facility for wool, but it was now a maintenance station, for the Trans-Siberian and the local lines, and I worked there. I had worked there for years. I repaired the insides of the train cars. I ripped out the old seats and bolted in new ones. I checked the safety windows, the luggage compartments. I found the things passengers dropped into the crevices — money, house keys, the backs of earrings — and I brought them to the lost and found. Because of my leg I had to rest often, but I had been there the longest and they let me work alone and at the pace I wanted.

Sometimes I stayed on the trains I repaired and went a few stops with the conductors. I liked trying the new chairs. I liked watching the country pass. When I was a child my mother used to take me as far as Vladivostok, but I never went that far now. I didn’t want my father to worry.

Our home was three hours north, at the start of the valley. I lived in my father’s inn. This was in Primorski Krai. The Maritime Territory. My grandparents had moved here. Kostya’s had as well. They were Korean refugees from the Second World War. They had come from the Pacific, from Sakhalin Island, where they had been forced to work in a Japanese labor camp.

After the war, when they were released, there was nowhere to go, nothing for them to return to. So they settled here, in the Far East. They found work and started families of their own.

Kostya used to work in the rice fields with his father. But when his father died, he came to help at the inn my father started. It was a busy time for us. It was beautiful country, and people visited or passed through. We helped guests with their luggage or vacuumed the lobby. We cleaned the rooms together. Sometimes Kostya would notice me rubbing my leg and he would say, “Misha, go rest on the bed,” and he would finish for me, all the while talking about a book he was reading, an adventure story, a hunt.

He liked books. When she could, my mother would bring one back from the city for him. Then he would vanish for hours and I would go looking for him. I would walk through the fields surrounding the town, through the high grass, until I felt something enclose my ankle like the soft mouth of a dog. I was expecting it and yet it always startled me. I slipped down and there he was, sitting there with the book on his lap. So I stayed with him.

Kostya who always slowed for me.

For a while there had been no lights along the landscape, but now we could see the distant windows of the farms and, as we headed into the valley, the town.

He asked how the leg was, and I said, “Good. It’s better now.”

It was how we met as children. He had made fun of the way I walked.

Suddenly there was a noise. Kostya stopped. He could always hear the planes before I did. I caught the quick shape of it flying over in the dark. I tried to make out Kostya’s expression but there was just his head tilted and his eyes under the evening. He was still carrying my bag.

A military base was nearby. They often did their practice runs in the evening. I knew this because Kostya had flown with them. I saw very little of him then. He would come back during a furlough but that was all. I wasn’t supposed to know where he was but I knew that everyone on the base was in Chechnya during those years. The seasons grew slower, and for extra pay I started working at the maintenance station.

A military base was nearby. They often did their practice runs in the evening. I knew this because Kostya had flown with them. I saw very little of him then. He would come back during a furlough but that was all. I wasn’t supposed to know where he was but I knew that everyone on the base was in Chechnya during those years. The seasons grew slower, and for extra pay I started working at the maintenance station.

When Kostya came home, he stopped flying planes. I thought he would come work with me at the station but he stayed at the inn, cleaning the rooms. He didn’t seem to mind that there were fewer guests, less to do. I would come home sometimes to find him cleaning a tub, trying to remove a stain that was many years old. “Kostya,” I would say. “It’s good enough.” And he would smile and nod, put the cleaning supplies away, and head to his room.

I wondered now whether my father was worrying about me. I wondered where Kostya was sleeping tonight. He had yet to mention his house. I didn’t want him to see it. But we were approaching the split in the road. If we went straight we would go down a slope farther into the valley and enter the town. The road on the left was narrower and still unpaved, with a sign that directed travelers to a small lake.

I took my bag from him. I said, “Kostya, where are you staying? Let’s go to the inn.”

But Kostya ignored me and turned onto the dirt road. So I followed him. It was the one road that had remained unchanged since we were children, except for the lamps that now shone on the path and the surrounding grass. We used to play soccer here. Or I would try.

The lake appeared. It was the only moment tonight when Kostya walked faster than I could. I let him. He kept slipping in and out of the light of the road lamps. I could see the reflection of the mountain in the water.

We were nearing three houses that stood behind a line of trees. Kostya had been born in the middle one. I thought he would enter the short pathway toward the front door, but he simply paused and looked across at his old house and the two others, keeping his distance.

None of their lights were on. The houses had been empty and in disrepair for a while now. The roofs were broken by the winters. Sleeping bags and empty bottles littered the front lawns. Kids used the houses for parties. From the town, I could catch their flashlights in the trees, or the smoke of a bonfire. Hear their music, the bottles they broke.

Kostya walked into the field, toward the lake. He found an overturned canoe with a crack in its hull. He brushed the dirt and the weeds away and sat down. I sat beside him, rubbing a knot in my leg.

“I’m sorry, Kostya,” I said.

“I was thinking of working on the house,” he said. “I could fix it up.”

“I’ll help,” I said.

In the dark I thought he smiled.

“Yes,” he said. “We’ll work on it.”

We had lost a ball once. It floated into the center of the lake and I was the first to swim out. It never occurred to me that my leg would cramp up, and I panicked, I went down, and for a moment I felt nothing. It was as though I had found a different place, something far greater than a lake, and it was wonderful to me. I wanted to stay. But I was pulled up. Kostya dove and pulled me up.

A radio tower was blinking on the mountain. It looked like a single tree on the far ridge. On the island, our grandfathers had felled trees. Then, later, they mined coal. They were kept there for six years, through the war, never knowing where they were exactly in the world. They even met men who were unaware that they were on an island. They had left Korea in a cargo hold and arrived dehydrated and disoriented, and for six years they worked. Our grandfathers worked while the bodies of those who didn’t survive were carted away. They worked as planes flew overhead, erasing briefly the sounds of the sawing and the drilling and the coughing.

Once a month they were brought to the sea. They were given time to bathe. It was the only time the guards didn’t seem to care what they did. Someone always tried to escape. One person always tried to swim. The guards let them. And our grandfathers would say nothing and hurry to clean themselves as the man vanished into a swell, rose, kept going. Sometimes they would come back a month later to find an unrecognizable body on the shore, picked at by the birds.

When I was young I didn’t understand what an island was. I used to believe the camp lay just beyond the mountain range. That they were right there. I used to hold my grandfather’s ruined hands and feel the curve of his spine and wonder if the misshapen bones in my body were from him.

“Kostya,” I said. “Were you looking for me? When you were on your way to the station?”

The radio tower continued to blink. We hadn’t moved from the canoe.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I was just looking.”

He had brought nothing with him. During the war in Chechnya I used to listen to the radio as often as I could. Whenever Kostya returned I asked him how bad it was. “Not bad,” he always said. And in the years following I forgot that he had gone at all, the two of us living together at the inn the way we did when we were younger.

I used to hope that he would take me into the air. But he never did. I would get angry at him. I would act like a child. And he would let me. He would stand there and let me say things to him. And I remembered this now. And I remembered how much I had once missed him.

Something skimmed the surface of the water. We heard it. We followed the wake.

It was bright in the town but the streets were empty. Only the grocery store was open, with a song playing on the radio. A boy pedaled by on his bicycle, turning to look at us as he passed. We watched him vanish into an alleyway.

“Where has everyone gone?” Kostya said.

I looked at the houses we were passing. I had not been looking at them lately. I didn’t know. Novosibirsk. Vladivostok. Farther. Seoul. Tokyo. Shanghai.

My father’s inn was three stories tall and the last house on the street. The sign was lit but the inn was closed. He had begun to close it in the evenings, retiring to his room earlier. I looked up to see if he was awake, but his window was dark. He had left the entrance light on for me, which he always did.

I turned the locks, and as we went inside we were met with the familiarity of a place that was older than us: the fireplace and the furniture, the striped wallpaper.

“Is he asleep?” Kostya asked, and I nodded, putting down the bag in the hall.

“He’ll want to see you,” I said, but Kostya raised a finger to his lip.

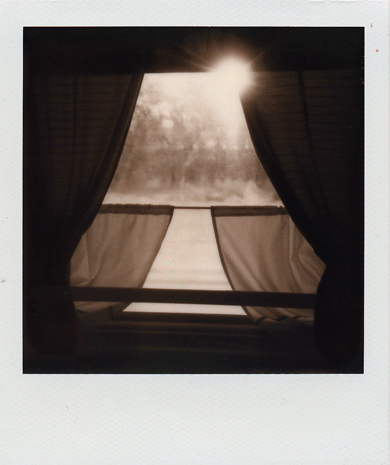

As I came inside, the air felt stale to me. I went and opened a window, reminding myself to shut it before the morning.

Kostya hung his jacket on the rack the way he always did before fetching the cleaning supplies from the closet. How diligent he had been. How hard he had worked under my father.

With a lightness he now stepped around the desk and turned the television on. The sound blared, briefly, before he muted it. A game was on. It was a game from a week ago that I had already seen.

He settled into the chair, wide-eyed, and watched. It was as though he had not seen a game in a long time. Inside, under the ceiling lights, I could see the years on him: his thinning hair, the wrinkles around his eyes. His frayed clothes. He was thinner than I remembered, gaunt.

I went into the kitchen and looked for some food. I made us cheese sandwiches with mustard. I brought the plate and two beers to the desk. He reached for the sandwich without looking and took a bite and drank the beer.

The clock read eight o’clock. It had felt earlier to me. I didn’t know where the hours had gone. I wanted to talk to him but I didn’t know what to say. I gathered a stack of bills I had yet to pay and put them on a shelf. Then I sat at the edge of the desk. He kept staring at the silent television.

“Kostya,” I said. “Where have you been?”

I could see his eyes track the ball across the field.

“Kostya,” I said again.

I gave up. I was suddenly aware of the age of this house under the old lights, the old wallpaper and the old wood and the old smell in the air. The outdated television. I was suddenly embarrassed. I didn’t know why I had brought him here. I didn’t know what to do. I stopped.

There was a photo on the desk. It was of my mother, Kostya, and Kostya’s father. They were in front of the inn, their hair wild from the wind. My father had taken the photo. I could never remember where I was on that day.

“Do you ever think of her?” Kostya said.

Then he said my mother’s name and it startled me. I drank my beer. I couldn’t remember the last time someone had spoken it out loud, the last time I had heard it.

She was a teacher at the local school and I used to wait for her to appear down the street, wait for her to come back to the inn. Even though she was tired from her day she would take me around town, and if she had money for it she would buy me an ice cream.

But most days she brought me back to the school, to the room where there was a piano. She would unlock the blue door and sit beside me and teach me scales, her hands moving across the keys like birds. Then I watched as she played something from memory, never sure where she had learned to play or who had taught her.

She did this every day in her last year with us. How I loved approaching that door. The shape of it, like the hull of a ship. The way she would stand there in front of it and tell me to wait as she looked up and down the hall, fumbling for her keys. To sneak in and play the school’s piano with me. As though preparing us both for some new future.

It was strange to think of them now, her and my father. To think of what promise they had contained in each other. A child of Korean refugees and the Russian woman who was staying at the inn one day. The woman who had come back.

That was all I knew of that story. They had me. They had tried.

“It was a long time ago,” I said. “No. Not really. No.”

“You’re never angry with her?”

“No, Kostya. I’m not.”

He considered this. I wasn’t sure whether he believed me. It didn’t matter. He caught me looking again at the photo.

“We used to always wonder where you ran off to. You and your private life. Your imagined worlds.”

I told him he was the one who had always wandered off. Him and his books.

He didn’t respond to this. On the television a goal was scored, and he watched the silent shouting, the running.

“I miss the air,” Kostya said. “Do you know this feeling? You’re living whatever day you’re in and you suddenly feel a longing. As though there has been an absence in you all this time and you never knew. But you don’t know what it is. You can’t find it. And it eats at you. For days it eats at you. Do you know it? I think I was missing the air. The takeoff. The first bank you make, the first turn. The world tilts, you look down. And then you go higher. I was missing that. I think that was what it must have been. Because I don’t feel it when I’m up there. I feel, instead, held.”

He wasn’t paying attention to the game anymore. He had picked up a pen. I watched as Kostya leaned forward and colored in an old scratch on the desk.

“You used to look for the bodies,” he said. “The victims of the camp. Do you remember? You were very young. It was before your father told you where the island was. And about coasts and oceans. You used to think the island was here. You would carry a shovel around, digging. Convinced you were living among ghosts. And I followed you. I helped.

“I helped until the day my father caught us. But he couldn’t hit you. You see, Misha, there was your limp already. He felt sorry. We all did. So he went after me. He took your shovel and he went after me. And as he approached I thought he would strike my face. What surprised me was that he didn’t. He hit my stomach. The way you would use a bayonet. The tip of the shovel ripped me open, and I think he would have pushed harder if he hadn’t woken from wherever he was.

“When I think of that day it’s never the pain or what happened or what we were doing or the shovel or even how young we were. I think of where my father was in that moment. Where in his mind he had gone. I had never seen that from him before and I never did again.”

Kostya put down the pen. We heard the floor creak upstairs. I thought my father must be awake.

I said, “I’ll go get him.”

“Tomorrow,” Kostya said. “I’ll see him tomorrow.”

I reached over him and selected the first key I could from the wall. I placed it in his hand. I was standing behind Kostya now and I wrapped my arms around him and rested my chin on top of his head. I smelled the earth in his hair. He smiled again, jangling the keys.

“What’s the rate?” he said.

“On the house,” I said.

“On the house,” he repeated.

That night Kostya slept in a room on the top floor. I brought him up. The rooms were all clean and the beds made. As I shut the door, I could see him sitting on the edge of the bed with his back to me. In the hallway I passed the faded botanical drawings my father had purchased a long time ago.

I went down one floor. My father’s room faced the street, above the reception. Mine was on the ground floor and he stayed up here. He always liked being slightly above. His room was decorated identically to the others. He always said that if it was good enough for the guests, it was good enough for him.

I had been wrong earlier. I must have heard something else. I opened his door to check on him and he was asleep in the dark. His body and his blanket illuminated by the hallway. I was about to step out, but he heard me and woke.

“Misha,” he said. “Is everything all right?”

I could hear the pull of a dream in his voice. I stepped in. I sat next to him. He turned on the bedside lamp.

He repeated what he had said, and I smiled. I said, “Yes, yes, everything is fine.”

I wanted to say that Kostya was here. But I kept myself from telling him for a little while longer.

I just wanted to be with him. I reached for his hands. I settled them onto my lap. His knuckles were cracked and dry. His lips were dry, too. I looked at his face. At his tired face that smelled of sleep and was speckled with moles, and I brushed back his gray hair.

I asked whether he had taken some aspirin. For his hands.

But he was falling asleep again. He was shutting his eyes. He said, “Misha, it’s going to snow. Not tomorrow, but soon. Don’t forget the spikes for your boots.”

His grip on me loosened. Outside the window the boy passed again on his bicycle. I could hear the spin of the wheels. Then I heard the light turn off above me. I wondered where the moon went. And then there was nothing, only the buildings of this town and the mountains.

Kostya stayed with us for a little while. In the mornings he would walk with me to the maintenance station. I thought he could work with me this time but he never went in, only waved. “That’s okay, Misha,” he said. “Have a good day.” And then he walked back to the inn, where I would find him in the evenings.

I liked looking at them through the window, Kostya and my father sitting near the floor lamp, the two of them tracing the arc of something in the air, talking.

“It’s good now that you’re here,” my father often said to him, taking his hand.

And it was. And I thought it would go on like this, the three of us together at the inn, not minding so much that there were no guests anymore.

But as the months went on we began to see less of him. He wouldn’t say where he went or what he did. He would return late or not return until days later, avoiding us. And then, like before, we didn’t see him at all.

I went to the air base a few times. I stood at the gate and asked the guard whether Kostya was there, but he wouldn’t say. The guard was only a boy. He went back to reading his magazine. When I didn’t leave, more guards came and took my arms and my shoulders, and they led me back to the road. One of them was older and recognized me. He knew I always failed the exams, and he told the other guards.

He said, “Friend, you can’t fly with that leg,” and then from behind the gates they said something about the inn, something I couldn’t hear from the road.

I walked to the field where I had first seen Kostya. I waited at the lake. I waited by the canoe, listening to the kids having their parties in the old homes. I kept looking up, for the airplanes. Then, one day, I stopped looking.

Winter started. It began to snow. And then the snow settled and didn’t go away. I put spikes on the soles of my boots and a liner in my coat. I went to work and brought dinner home from the grocery store.

One night, replacing the chairs of a train car, I fell asleep. When I woke my left hand was in a bowl of warm water and two conductors were sitting beside me, grinning.

“It didn’t work,” they said.

“Misha,” they said. “You were supposed to piss your pants.”

I waited for my eyes to adjust. It was bright, daytime. I saw the blue of their uniforms and then I looked out the car window. I focused on the great pale arches of a building looming over the tracks. I wasn’t sure where I was.

“Vladivostok Station,” they said.

I sat up, awake. I moved too quickly and felt a muscle in my leg tighten and pull. I knocked the water over. They laughed. They rose and helped me up. One of them took out his handkerchief and wiped my hand. Then whatever mischief escaped from them, and they looked at me with a tenderness I had never seen in them.

“Misha,” they said. “We didn’t want to wake you. You have an hour before we go back. It will be the local. Get some air, Misha. See the city. Have a coffee. Go shopping. Go find a woman.”

They hit my shoulder.

“Go,” they said.

I stepped out onto the platform.

“Just don’t miss the train!” they shouted, and laughed some more.

I entered the station. I passed through the waiting room where there was a mural on the ceiling of a skyline. I passed the chandeliers, the arched windows. Passengers already waiting on the blue chairs for their trains.

I hadn’t been here since my mother had taken me. We would come twice a year to shop. She was a city person, had always preferred it to where she was. The city was where she bought my father clothes. School supplies. Coloring books. And then the secret gifts. A small perfume for herself. Candy for me. I used to watch the way she would dip the bottle against one wrist, her arms suddenly alive with the smell of flowers and herbs. I would lean against her on the train ride back, slipping my fingers under the band of her wristwatch as the country passed.

Where did she go? We never knew. Or if my father knew he never said. But I didn’t think he did. I used to imagine her here alone, waiting for wherever she was going. In the room with the mural and the chandeliers. On the train platform. Wearing her long coat. My mother, Lidia, at the Vladivostok Station.

I went out into the city. I crossed the main road and headed toward the port. I stopped at a café and had a coffee. The woman behind the bar noticed my railway uniform under my coat and she gave the coffee to me for free.

In the distance, cargo was being loaded onto a ship, the arm of the crane pivoting in the gray sky. It was warmer here than in the mountains but still cold, the rain gutters and the edges of roofs already cluttered with icicles that would last and grow for months.

It was then I saw a bookshop. It was near the water, on a street corner. I approached the windows first, seeing what books they had on display. I thought that in another life I would like to make book covers. I didn’t know whether that was something one could do for the rest of their life, just that today, this morning, it made me happy thinking of it.

I had time. I went inside. The man behind the desk greeted me. I browsed the shelves. I saw novels and history books and books of poems. I wanted to buy one. I checked my pocket and realized my wallet was in my bag, which I had forgotten in the train car. I had only some coins, not enough. I promised myself that I would come back one day and buy a book.

I returned to the street and approached the harbor. The sound of the ships and the machines grew louder. The birds. I could smell fish. Engine oil. A vendor was selling peanuts on the small boardwalk, the steam rising into the air. I walked to the first pier and then back. I saw dockworkers in their thick gloves, their faces covered in masks to keep warm. I saw a ship with Japanese characters painted on its hull.

There was a telephone booth at the end. I slipped inside. Flyers with naked women were scattered on the floor. I took out the coins, pushed all of them in, and dialed. The glass of the booth was dirty and already fogging with my breath. I wiped it away. I was facing the harbor.

I didn’t know if he would pick up. It kept ringing. I wondered if he was still asleep. Or if he had gone somewhere. I wondered where he might have gone. Where we would go.

A train whistled.

And then he was there. He picked up.

I held the telephone and looked out.

“Dad,” I said. “I’m by the sea.”