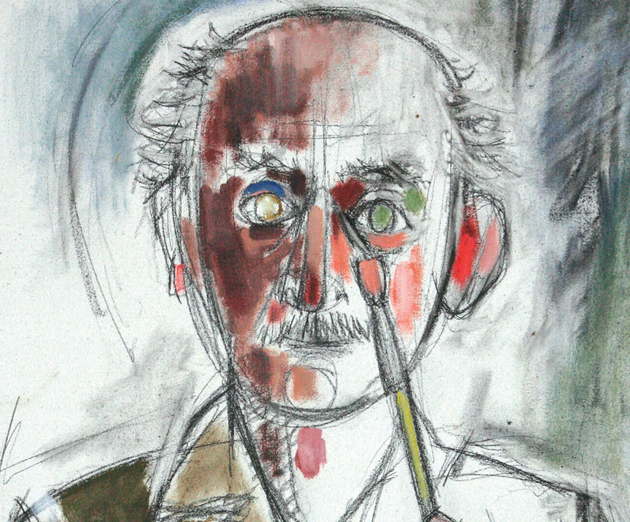

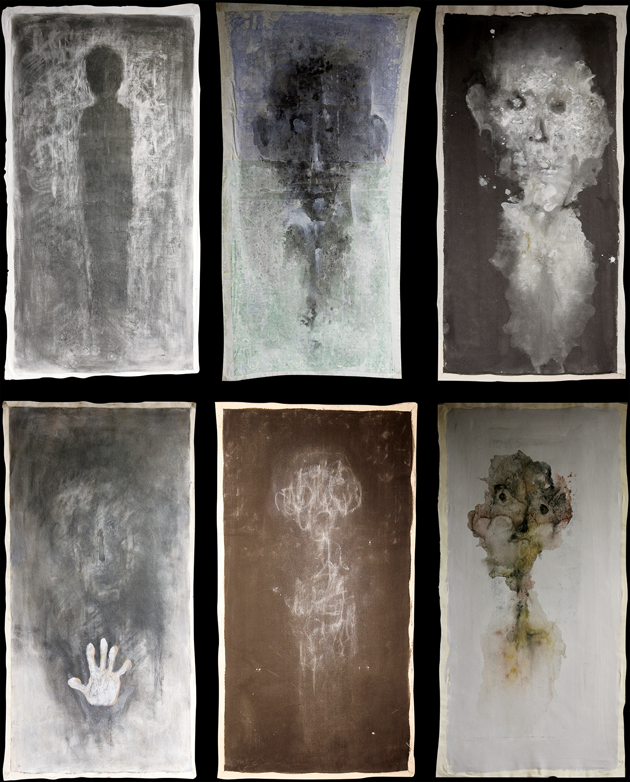

Si Lewen’s ghost is hanging in my studio — or, more accurately, I should say that one of Si Lewen’s “Ghosts” hangs there. The artist painted about two hundred of these haunted and haunting figures in a series he began in 2008. He gave me my “Ghost” the first time we met, at his rest-home condo near Philadelphia back in the spring of 2013. Si was ninety-four years old then, a dynamo: a charming and elfin man, frail but bubbling with enthusiasm, wry humor, and unorthodox opinions. He spent his long days in the small second bedroom of his apartment — he had turned it into a fully functioning, miniature-size painter’s atelier — working on his canvases, as he had most of his life.

I asked if he had any friends who lived at the facility, and he waved me off. “Nah! They’re all too old for me — ghosts! Besides, I was always a loner.” In his German-inflected English, he went on to say, “You know what keeps me going, Art? CURIOSITY! I want to find out what I’m going to paint tomorrow!”

I heard that line often in our subsequent phone conversations, though since early 2014, he has slowed down considerably. Instead of telling me that every morning, between sleeping and wakefulness, ideas for paintings would start clamoring for his attention, he has begun reporting that when he wakes up it takes him quite a while to figure out if he is still here or has already died. He is an atheist — the son of a highly regarded atheist Yiddish writer and a mother who was the direct descendant of a famous Hasidic wonder rabbi, the Seer of Lublin — but Si is the most God-fearing atheist I’ve ever met.

He had been aware of graphic novels and my work before we knew each other, and in 2011 he talked about the form at the Michener Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, at an exhibition of drawings from A Journey, a story in pictures that he drew in the 1960s. He has continually tried to convince me to become a painter, since “comic books don’t last, but a painting can be seen and appreciated forever, for centuries after it’s painted!”

After we made contact, I began to appreciate the breadth and depth of Si’s lifetime of work as well as to learn more about the fraught and full lifetime that shaped the work. He was born in Lublin, Poland, on November 8, 1918, just as World War I ended. The family moved to Berlin when he was almost two to escape Polish anti-Semitism, only to discover the German variant. Taunted by the German children, and his teacher, as “that Polish Jewboy,” Si retreated from contact with others, and, by the age of five — having been given some paints to occupy him while he was confined in a Swiss sanatorium when suspected of having tuberculosis — he declared himself a painter. Long and repeated visits to Berlin’s art museums with his parents from toddlerhood on were his joy and the core of his education. Si told me that various paintings had spoken to him, but he wished they had been hung closer together “so they could talk to each other.” This observation planted a seed that would come to fruition years later in his mature work.

The young atheist resisted a traditional bar mitzvah, but made several dozen drawings to illustrate stories from the Bible instead. A few months later, he had his first exhibit in the small back room of a local bookshop, and began to sell his artwork. One oil painting of miserable workers trudging through the snow proved especially popular — it was “full of weltschmerz,” Si said — and he secretly made multiple copies, each of which he sold as the original. He felt his art career was off to a glorious start. It was dramatically interrupted in 1933.

Very soon after Hitler became chancellor, fourteen-year-old Si presciently insisted on fleeing Germany. He and his older brother Isaac, a little over sixteen, left the family behind and took a train for Paris, staying briefly with friends of their parents (where shy Si lost his virginity to their hostess, by the way), and then traveled to a farm in the Loire Valley to learn skills that might help the two young refugees emigrate to Palestine.

By a miracle involving a wildly successful plan to raise private money for Admiral Byrd’s expedition to the South Pole through the selling of a commemorative stamp — organized by an uncle of Si’s in America who ran the numismatic franchise at Gimbels department store — a grateful Senator Harry F. Byrd, the admiral’s brother, arranged impossible-to-get visas for the entire family to immigrate to America in 1935.

One of the two traumatic events that permanently scarred the young artist brought Si’s first euphoric year in New York to an abrupt end on a summer afternoon in 1936. Sitting by the lake in Central Park after one of his many visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he was beckoned over by a policeman in a rowboat who, on hearing his accented English, rowed him out to the center of the lake and bludgeoned him repeatedly with a blackjack — robbing him as he hurled anti-Semitic epithets. Aiming a gun at Si’s head, the policeman warned him not to tell a soul about what had happened or he’d come find him and kill him. Bloodied, in pain, humiliated, and terrified, the refugee — an outsider even here in his “promised land” — made his way home. Deeply depressed, Si tried to poison himself a few weeks later — his first near-fatal suicide attempt — and was committed to a mental hospital in Westchester for observation. Only after meeting his future wife, Rennie, a year and a half later, did he begin to come to terms with the assault, which has haunted him all his life. He was unable to tell her, his closest confidante, about it until after more than forty years of marriage.

In 1942, Si married Rennie, shortly after enlisting in the army. Wanting revenge on the Germans, he temporarily overcame his pacifist inclinations and joined an elite intelligence unit of native German speakers, mostly young immigrant Jews like himself, who were trained at Fort Ritchie, Maryland, and used in translation, espionage, and psychological warfare. Si’s primary duty was to broadcast from a sound truck at the battlefront to persuade German soldiers to surrender. Landing in Normandy nine days after D-Day, Si traveled along the front lines and into Germany, where he encountered his second lifelong trauma: witnessing the Buchenwald concentration camp shortly after it was liberated. Surrounded by living skeletons and the smell of death, he wandered into the recently cooled crematorium. Having steeled himself through combat and with the help of schnapps, he broke down sobbing and — deeply shaken — fled. As he later wrote in Self-Portrait, his unpublished memoir: “My insides were one wrenching mess. I knew that I was finished as a soldier, seeing the world for what, I thought, it was: a slaughterhouse, a bordello, and an insane asylum, run by butchers, pimps, and madmen. . . . A hospital ship brought me back to America, and half a year later I was discharged — ‘as good as new,’ one of the doctors said. I was not so sure.”

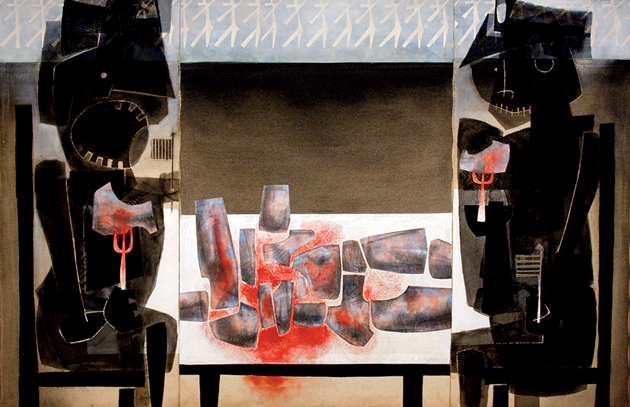

Back in America, Si was surprised to find that, when he picked up his paintbrushes again, his postwar works eschewed blacks and were suffused in dappled layers of color, forming a prismatic Cubism with an Expressionist edge. They gave him a way to put the dark past behind him and were greeted with commercial-gallery success. His work began to appear in museum exhibitions in the United States and Europe. The fourteen-year-old dropout now taught art at Cooper Union, and then at the New School as well. The birth of two children — Vivian, in 1947, and Nina, in 1949 — made his future as sun-drenched as those paintings.

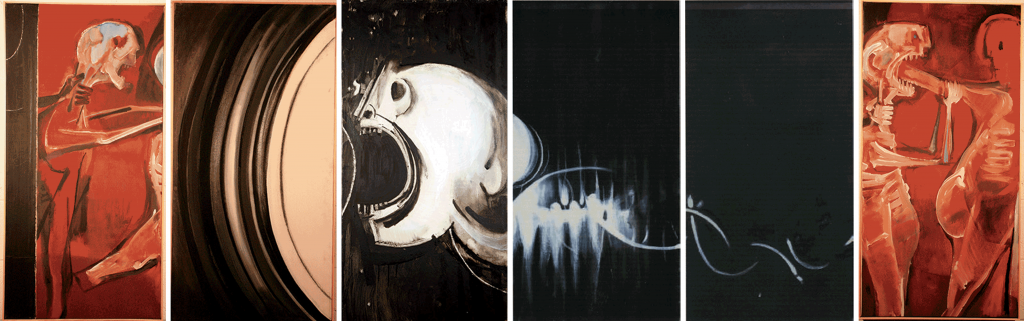

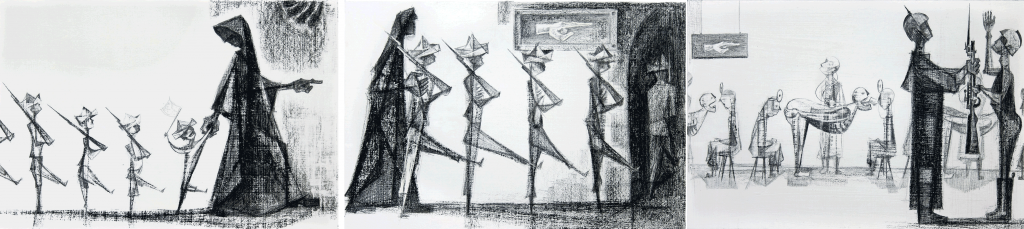

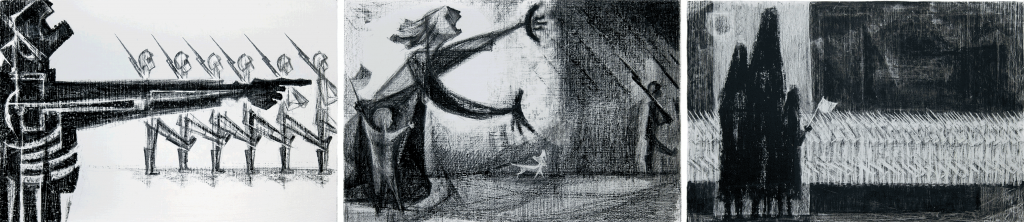

Still, by the turn of the decade, Si’s turbulent memories and feelings of displacement began to reassert themselves. “My world of translucent color and light was turning into transparent lies,” as the artist put it. By 1950, Si was pursuing an idea that had begun to gestate while he was still a soldier. Inspired by a lifelong love of movies — and in conscious resistance to the pure nonrepresentational abstraction that was coming to dominate contemporary art — he made The Parade.

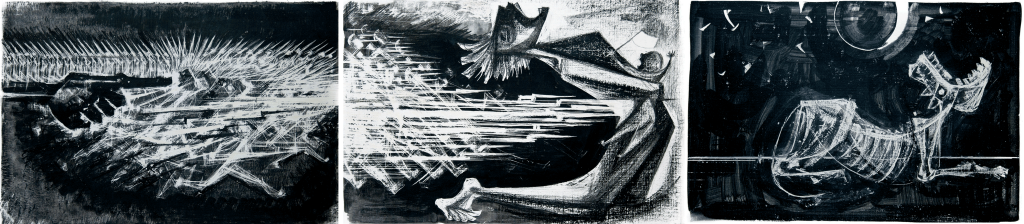

The work begins with an excited crowd of flag-waving parents and children who gather to cheer a military procession of soldiers that turns into an abstract engine of war. Little boys playing with toy guns are beckoned from the arms of their mothers into the arms of a shrouded Grim Reaper, who transforms the children into helmeted, goose-stepping cannon fodder — interchangeable cogs in a relentless war machine. A series of vignettes focuses on scenes of escalating havoc and suffering — the disasters of war — replete with bayoneted mothers and babies, terrorized families fleeing bombed-out cities, and devastated farms. The images accumulate into a panoramic harvest of blood and death. The parade turns into a hanging row of severed heads, a procession of the wounded and maimed, a march of ravaged survivors staggering under the weight of the coffins they carry.

A gray smoke-filled sky with a few birds finally gives way to a simple, somber image of exhaustion: the bodies of two soldiers each slouched over the other in a death embrace, pierced by each other’s bayonet. A swirling and manic “victory” dance of the survivors immediately follows. In front of the ever-present flag-waving crowd, a small yapping hound — one of the many dogs of war running through The Parade — continues to bark as a mother protectively gathers a child with a flag to her bosom. This is a powerfully moving free-jazz dirge of a book that depicts mankind’s recurring war fever. It remains sadly urgent and relevant today.

In the fall of 1953, forty drawings from The Parade were shown at the Lotte Jacobi gallery in Midtown Manhattan, and described in the Sunday New York Times as having “a curiously impersonal yet intense feeling and are tremendously effective.” Lotte Jacobi, best known as a portrait photographer, had arranged for a version of The Parade to be shown to her friend and frequent portrait subject Albert Einstein two years earlier. Einstein wrote Si a glowing letter, stating, “Nothing can equal the psychological effect of real art. . . . Our time needs you and your work!” Reviewers of the exhibit and the eventual book, published in 1957, compared the work with Goya’s Disasters of War, the drawings of Käthe Kollwitz, and Picasso’s Guernica. Si was always artistically ambitious and aimed to be part of this pantheon, but in a 1963 interview, when asked what his future plans were, he responded, “To put one foot in front of the other, as I’ve always done.”

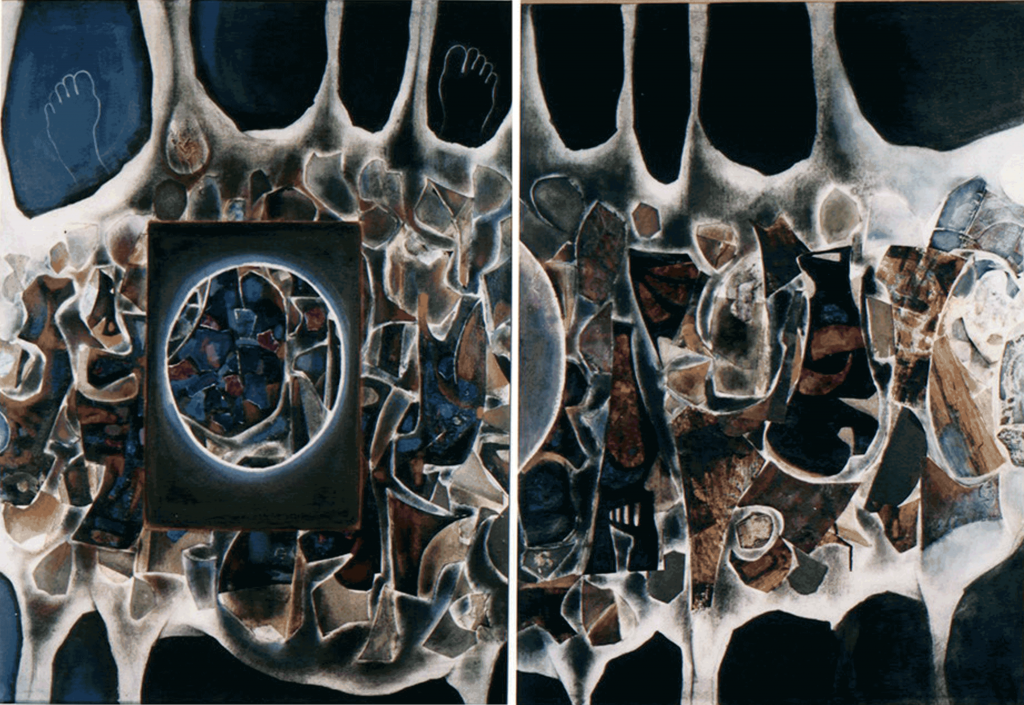

In the early 1960s, Si followed The Parade with another story in drawings, A Journey, a work more personal, albeit less universal, than his emotionally resonant Parade. Soon the two books of sequential drawings rather organically developed into painting sequences on canvas — often incorporating his developing approach to collage — in a project he called The Procession. Going well beyond diptychs and triptychs, Si began to produce a very long “multiptych” — extending imagery from one panel to the next, cinematically “intercutting” these panels with others in very different styles and moods. This was his childhood vision of putting museum paintings close together so they could “talk to each other.” Although The Parade and A Journey are probably the most overtly narrative series Si ever made, these serial paintings unabashedly traffic in time as well as space. Putting one image, as well as one foot, in front of the other became his operating principle.

The long Procession of mostly figurative twenty- by forty-inch canvases, begun in about 1960, kept growing over the years until there were more than 1,800 panels. In 1963, The Procession was joined by another developing series, Centipede, thirty-six- by forty-eight-inch morphing images that Si intended as “one hundred feet of continuous, panel-by-panel progression. . . . A serpentine creature evolving into figures, into landscape, breaking up into floating rocks, suns, moons, and galaxies, joining again into perhaps a snake turning into a mountain range, and on and on.” It quickly outgrew its original name and was rechristened Millipede — finally expanding to more than three thousand feet of panels.

In 1967, Si began withdrawing his work from commercial galleries, and by 1985, after he officially proclaimed that “Art is not a Commodity! Art is Priceless!” his opportunities to be included in museum shows began to dwindle dramatically. But he still wanted his work to be seen, just not owned. He tried to set up a system somewhat like a public library that would “loan” paintings to anyone interested who signed an agreement not to sell them. He was surprised to find that other artists didn’t follow his example.

When art is priceless, it is also — as Si was quick to note — worthless. This pushed him not into retirement but into a torrent of productive activity that did not abate until 2014. Si plowed under earlier “worthless” works and redeployed them in his new ones with impunity — shuffling, rearranging, and adding to his mostly undated serial paintings. Images of walking figures, mountain landscapes, soles of feet stacked up as if in concentration-camp barracks, feathered Indians, dancing figures, and celestial constellations kept coming up in the mix. No longer even vestigially tethered to any style, the paintings swung between looming tormented heads and bubbling, erotic panels of colorful biomorphic abstractions.

One short evocative series called Eva, made in 1994, consists of figure paintings of a naked woman, often doubled over in pain. With no indication of which side is up in the forty- by forty-inch paintings, no identifiable background, and no consecutive numbering, they evoke an adult creature floating in vitro.

Shortly before moving to the condo where he now lives, Si had abandoned an epic project of at least 330 pieces, The (Unfinished) Odyssey of Si Lewen, 1918–. It’s an autobiographical work: an assemblage of family snapshots, occasional printouts from his unpublished memoir, postcards from his far-flung vacation travels, details from his seventy years of older paintings directly collaged or sometimes photocopied and extended into newly painted images, all on twenty- by thirty-inch stretched canvases, like the dummy pages of an enormous book designed to be placed end to end across the sky. Some kind of graphic novel, I guess.

Though most of Si’s series are far from traditional narratives, many hold a special interest for me as clues to one direction that comics might explore now that they’ve begun to be embraced by galleries and museums — not only as Pop Art or as exhibitions of original artifacts that were first intended for print publication but as allusive narrative works for intelligent adults looking at art made expressly for walls, willing to let a procession of canvases “unpack” their mysteries through repeated viewings. One can’t immediately understand what the pictures are saying, but one understands that they are indeed “talking to each other.”

In our regular phone conversations, Si began to complain about the pain in his right hand caused by rheumatoid arthritis. It had become excruciating to hold a brush, and nothing the doctors did helped at all. He’d announce his “retirement” in occasional emails, but it never lasted more than a few days, since painting was what kept him going.

At the beginning of 2014, I got a message from Si’s daughter Nina. Si was in the hospital. He had tried to cut off his right hand with the buzz saw he used for making canvas stretchers and had been found unconscious and bleeding in his condo the next morning, having scrawled the word “Enough!” on his studio wall in large brushed letters. As he convalesced, the doctors said they ought to put him in a mental hospital. Except that he wasn’t crazy. Si promised, “I’ll never do that again. I didn’t realize how hard bone is!”

As an extremely radical form of self-therapy, cutting through all the nerve endings in his wrist eventually stopped any sensation in his hand (including the rheumatoid arthritis) after his wounds healed. Back in his studio with a permanently useless right hand, Si tried to learn how to paint as a lefty, but he was unhappy with the occasionally interesting results. Although he did not have much history as a sculptor with either hand, Si thought he might get less frustrating results with his untrained left hand in a new medium. The “installation” I saw in his studio that spring made me gasp: more than a dozen white sculpted hands of different sizes and different degrees of abstraction jutted up from the floor — sometimes the whole forearm, sometimes just fingertips. It looked like a zombie apocalypse! No — more accurately, it looked like the severed hands from A Journey, the book he had drawn about fifty years earlier!

Very recently, I told Si I intended to write about all this, and he asked if I was going to tell the truth about his hand or say — as he had to some people who inquired — that it had been an accident. “The truth,” I said. He sighed and agreed. I tried to console him: “Hey! It worked for van Gogh — did wonders for his career!” Si laughed.

On February 12, 2015, Si’s wife, Rennie, died. A few weeks later, I visited Si in the new quarters he had moved into. He called it his “cave.” It was small and dark, but more specifically, he had painted directly on the walls as well as put up his paintings and tacked family photos everywhere. He had tried to continue painting by placing a plank on his narrow bed and kneeling in front of it, but couldn’t keep that up for long. He needs a walker to get around, sleeps more now, and listens to the classical music he and Rennie used to share. Like some clockwork toy whose gears are gradually grinding to a halt, Si has begun to shift his curiosity toward the possibility of an afterlife.

I reminded him that he’s an atheist, but Si has faith, if not in God, then certainly in the value of art (priceless) and in his own worth as an artist. Having made art the center of his world, Si Lewen has devoted himself to using art to express the core of his experiences, emotions, and convictions. Some of the styles and tropes he used are firmly fixed in what now looks like no-longer-modern Modernism, caught in the currents of Surrealism, Expressionism, Abstraction, and the other art storms he has lived through. Some of his work — the stylistic collisions and shifts, the juxtapositions forming series with temporal narrative beats — seems well ahead of its time. His horror at man’s cruelty and stupidity, his moral lucidity, seem prescient and right on time. It doesn’t take an Einstein to believe our time still needs him and his work.