Driving through Beverly Hills one afternoon this spring, I pulled over at a corner lot with a tennis court, a pool, a guest house, twenty towering sycamore and redwood trees, and an acre of emerald grass. I had arrived at the mansion of Lisa and Joshua Greer, their five children, and an American Staffordshire Terrier rescue. Although California is now in the fifth year of a historic and devastating drought, the Greers have kept their lawn looking as lush as if it were in Ireland. “I just didn’t want brown,” Lisa told me. Lisa runs a management-consulting firm; Joshua cofounded RealD, a company that makes 3-D glasses and sold last year for $551 million. Lisa was standing on her front walk sporting a Fitbit, designer sweats, and a perfectly coiffed auburn bob. “Some people are like, ‘We just let our grass go brown,’ and I’m like, ‘Really?’ I don’t know if that’s the right thing to do.” A stretch safari jeep packed with tourists was slowly rolling along the street. Lisa gave me the rundown: Jimmy Stewart’s old house was on the corner, Lucille Ball’s (“Lucy’s house”) was the Mediterranean villa across the street, the Gershwins were a few doors down, and Ella Fitzgerald lived a half block away. “Especially with these star tours all day long, I didn’t want our house looking like a dump,” she said.

Automatic sprinkler at 4:30 p.m., Beverly Hills. All photographs from southern California by Mike Slack

Lisa Greer’s sense of propriety about her yard is not uncommon in southern California. “You’re in lawn country,” one Angeleno told me. Down the coast and throughout the inland valleys, some 212,000 acres of thirsty turfgrass continue to be irrigated year-round, at tremendous expense, with billions of gallons of water imported from hundreds of miles away. For many people, a southern California house without a lawn would be like It’s a Wonderful Life without Jimmy Stewart. But there is also a revisionist view — the lawn as architect Elizabeth Diller described it recently: a “platform for controlled domestic growth, but also a sinister surface of repressed horror.”

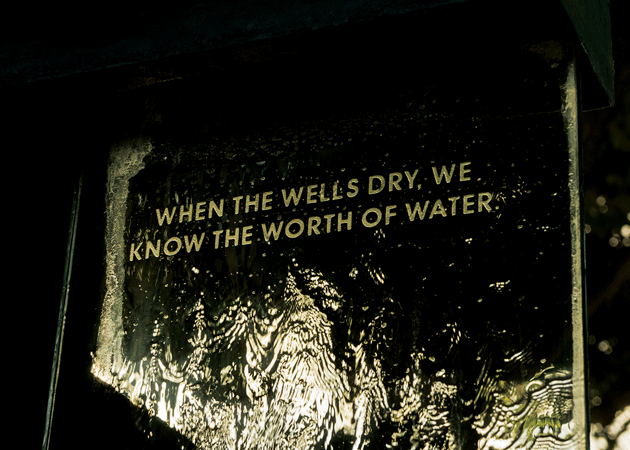

The Greers began to worry that their lawn’s days were numbered last year. On April Fools’ Day, Governor Jerry Brown had stood in a bare field in the Sierra Nevada Mountains — where the snowpack is usually five feet deep — and announced unprecedented statewide water restrictions. Urban areas, he ordered, were to reduce their total water consumption by 25 percent. To meet that target, individual cities and towns would be required to conserve different amounts specified by the state water board, ranging from 8 percent in cities such as Compton (small lots, with gravel, hardscape, or dead grass) to 36 percent in wealthy inland communities such as Arcadia (huge lots, with grass and flower beds). Brown also called for 50 million square feet of lawn (1,148 acres) to be replaced with drought-tolerant landscapes, which would save the state 488 billion gallons of water a year, the equivalent of 739,000 Olympic-size swimming pools. In his announcement, Brown declared: “The idea of your nice little green grass getting lots of water every day? That’s going to be a thing of the past.”

Since the state began keeping records, California has periodically experienced brief droughts, typically lasting around three years. Yet geophysical evidence indicates that the region has also known 200-year droughts, suggesting that modern California may have been built during an unusually wet century and is now returning to the drier norm. Compounding that possibility is climate change. The state’s snowpack — which, like a water tank, accumulates reserves all winter and spills down meltwater all summer — is disappearing.

When state officials saw that the spring’s snowpack was zilch, they were forced to start reckoning with the possibility that the drought wasn’t going to end. Water used on outdoor landscaping became an obvious and immediate focus, because in California’s urban areas, an average of 50 percent of the water supply irrigates lawns and gardens. “People don’t realize that,” Felicia Marcus, the chairwoman of the State Water Resources Control Board, told me. “They are routinely using this highly treated, precious, drinking-water-quality water to overwater their lawns.” Local water agencies pushed for turfgrass removal. The Metropolitan Water District, which sells water wholesale to cities and towns throughout southern California, serving more than 19 million people, offered $340 million in cash-for-grass rebates. (From the time the rebate was first offered, in 2008 — at a pittance of thirty cents per square foot of grass removed — to the time the drought was declared a state of emergency, in 2014, the program spent only $10 million.) Smaller water agencies had their own grass-removal rebate programs, too. Homeowners could combine the M.W.D. rebate with their local municipality’s and get as much as $3.75 for every square foot of lawn removed. The program “took off like gangbusters,” Jeffrey Kightlinger, the M.W.D.’s general manager, said.

In the Greers’ neighborhood, however, cash rebates meant nothing. As the rest of the state withered, Beverly Hills remained a world unto itself, full of rainbows glistening in sprinklers and rolled-out tracts of turfgrasses with come-hither names like Bermuda, Marathon, and red fescue. Pools burbled and leaked, and every dawn saw drenched sod. By October 2015, the city had failed to meet its conservation target, and the state water cops issued a $61,000 fine, insisting that Beverly Hills residents should be “ashamed.”

Local and national media couldn’t get enough of the story, and drought shaming went viral. The Center for Investigative Reporting revealed that the top water guzzler in Los Angeles — “The Wet Prince of Bel Air” — had used 11.8 million gallons in one year. The person’s identity was not publicly revealed, so Maureen Levinson, a member of the Bel Air–Beverly Crest Neighborhood Council, went in search of the culprit. “I’m just a mom with a camera,” she told me. She patrols the streets, a vigilante in a minivan, intent on exposing the most egregious water offenses in the hills to city officials. She also drafts policy recommendations, and her pursuit of the Wet Prince was likely a factor in the city’s imposition of a new, stricter conservation ordinance in late April.

The Greers began to worry that they might be targeted, and their water bills had become awfully high. Beverly Hills had introduced a new penalty structure: if customers did not reduce their water usage by at least 30 percent from their 2013 consumption, they would pay surcharges on an escalating scale. The Greers’ first bill under the new system was nearly quadruple what it had been before. “The penalty alone was five digits,” Lisa said. Outraged 90210 residents sent letters to city hall to protest the fees. The Greers, with the help of a landscape architect, decided to replace their lawn with Agrostis pallens, a type of bent grass native to the California coast, and to plant an evergreen ground cover called Myoporum between the sidewalk and the street.

I stood on the finished product and, had I not known better, I would’ve thought that it needed as much water as any lawn in Los Angeles. Though the project cost more than $100,000, Lisa said that she and her husband expected to make back the investment in less than a year, considering what they would have had to pay to keep their old lawn green. So far, the new landscape has cut their water usage by more than the 30 percent target. She held up an iPhone to prove it on Water Tracker, an app provided by the City of Beverly Hills. “I’m rabid,” she said. “I check it every day. I can see my water usage by the hour!” She tapped and scrolled, showing me comparisons by month and year. In March, the Greers were down by 42 percent from 2013. They hoped the results would continue.

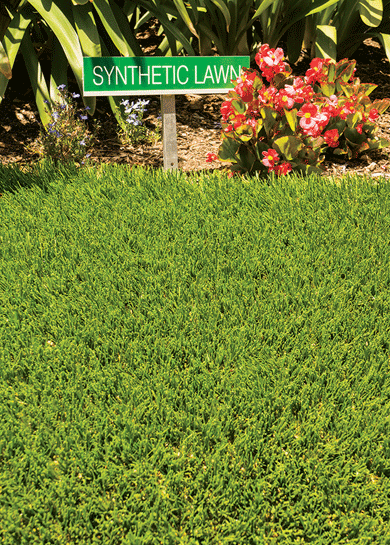

Lisa Greer, exemplar of California aspiration, seemed to have figured out how to have it all: the lawn of Hollywood dreams and the satisfaction of doing the right thing. Of course, most people can’t afford to install an acre of beautiful yet drought-tolerant sod. Most people either let their lawns die slowly (and maybe hire one of the companies that paint brown lawns green) or replace their yards with gravel, synthetic turf, or sandy xeriscapes dotted with rocks and cacti — all of which can be seen on a drive through Los Angeles.

Nearly two centuries ago, the English aristocracy’s idyllic lawns captivated a young American horticulturalist named Andrew Jackson Downing. In 1841, he published a book on landscaping that made the lawn the most common and unifying aspect of the American suburbs. In A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, Downing explains that if a man surrounds his home with a soft and refined lawn (mowed frequently with an English scythe), it “not only contributes to the happiness of his own family, but improves the taste, and adds loveliness to the country at large.” Americans, taking cues from the blue bloods, viewed lawns as a sign of affluence — a luxury, at first, and then a symbol of paradise in a prosperous democracy: arrival in the middle class.

This enchantment with claiming one’s patch of grass was lit upon by corporate America — sod producers, machine and chemical manufacturers, irrigation companies. Postwar suburban developments razed forests, wetlands, and coastal chaparral, replacing them with tract housing and a monoculture of turfgrass. Lawns are the single largest irrigated crop in America, according to a satellite-image study funded by NASA. The nationwide lawn-care industry takes in $77 billion annually, and its largest market is in California, where lawn and garden retailing are worth nearly $10 billion. The state is also the country’s top producer of turfgrass.

Southern California’s singular appetite for grass is largely thanks to Werner Gramckow, a former Nazi soldier who survived the Battle of Stalingrad and immigrated to California in 1950. When he got off the plane in Burbank on a hot August day, Gramckow recalls in his memoir, the landscape was the opposite of what he had imagined. “What the hell is this?” he muttered to himself. “So, this is a desert. Everything bone dry.” In the early Sixties, at the height of the suburban housing boom, he and a friend began growing sod for developers and landscapers. A decade later he started a wholesale turfgrass company in Oxnard with his son Jurgen, a Stanford engineering grad. The Gramckows’ business, Southland Sod, is now the region’s largest supplier of ready-made lawn. At its peak, the company was farming 1,800 acres.

By the late twentieth century Los Angeles was a city filled with tens of thousands of miniparks. (As the sociologist Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo writes in her excellent book Paradise Transplanted, the government and local developers didn’t invest in many public parks.) Everyone had a lawn, even the poorest people in the most troubled neighborhoods. But since 2008, with the recession and the housing crisis, and then with the drought, the lawn has started to become a marker of inequality once again, a luxury available only to the rich.

Werner Gramckow died a few months before Governor Brown announced the mandatory water restrictions. Southland Sod scaled down to 500 acres, and Jurgen Gramckow went on the offensive. In op-eds and TV and newspaper interviews, he criticized the government’s cash-for-grass program — what he called a “lawn bounty” — and extolled the environmental virtues of grass. He told the Los Angeles Times that Californians were “kidding ourselves that by scapegoating lawns we’re really going to change the paradigm here and have enough water to live happily ever after.”

The turfgrass industry, which is worth $40 billion, had Gramckow’s back. Turfgrass Producers International, a trade association, issued a press release with a photo of misty morning light sparkling around a single tree surrounded by greensward — the kind of dreamscape familiar to, say, Vermonters. The industry magazine Turf published a story warning landscape companies about new lawn-care techniques in California that “require significantly less maintenance, including less mowing and chemical use.”

By July 2015, Gramckow had laid off thirty of his employees, and his sales were down by half. When I called him, he made his case: “We’re not creating cancer here. All the negativity is really undeserved.” On the contrary, he went on, sod does more for the environment than “butterfly bushes” could. But most scientists would disagree. Alison Lipman, an ecologist at UCLA, pointed out to me that not only do native plants provide food for the region’s butterflies, bees, and birds, they also are better carbon sinks than common grass. You don’t have to mow, and the diversity creates complex and deep root systems that are better able to filter rainfall. Turf, by contrast, is a monoculture, she said, which is “pretty much non-biodiversity.” It sits on “dead soil,” so water streams off it, carrying toxic herbicides and fertilizers straight into the ocean.

Most residents of southern California don’t have a clue about which plants are native and which are not. Common guesses are cacti and succulents, though these account for a tiny percentage of all native plant species, of which there are approximately 6,500. California farmers grow and export the largest quantity of wholesale flowers and nursery products (including sod) in the country, with floriculture sales totaling a billion dollars, but they mostly avoid raising native plants. Megastores like the Home Depot and Lowe’s have more market power than ever, and sell few varieties. Over time, natives have been almost entirely eliminated from designed landscapes in favor of water-loving hydrangeas, azaleas, and impatiens. The horticulture guide California Native Plants for the Garden says, “For most Californians, native plants remain outside their daily experience, a vague veneer on the distant horizon.”

Recently, however, fans of Rachel Carson and Lorrie Otto, the anti-lawn environmentalist, have been gaining traction in their quest to kill the sod and fill gardens with native flora. Because of the drought, southern California is a booming ideological center for activists, writers, horticulturalists, landscapers, and scientists who see an opportunity — and a need — to move arguments that remained on the fringe for decades to the center of political debate. Even Randy Record, the chairman of the M.W.D., now says, “The only person who really walks on the lawn is the gardener every other week. What’s the point of having it?”

Lisa Novick is a leading member of the native-flora movement. She is fifty-nine, with prominent cheekbones and large green eyes, and works at the Theodore Payne Foundation, a nonprofit nursery dedicated to California’s native wildflowers and plants. She invited me to her house, in the wealthy L.A. town of La Cañada Flintridge, where for fifteen years she has played the role of genial antagonist. Big lawns and ornamental gardens still predominate, and Novick is not shy about confronting her neighbors about their extravagant yards. “I’m a pariah here,” she told me. She shrugged, and seemed almost amused.

Novick’s yard looked ecstatically alive, as if it were breathing. The shrubs and small trees were thrumming: native bees buzzed in black sage, a butterfly floated above a manzanita shrub, bushtits flitted through the branches of Santa Cruz Island buckwheat. The garden smelled like an earthy revelation, making every inhale semi-intoxicating. All of Novick’s plants are natives, requiring minimal water. But in 2015, La Cañada Flintridge was cited for having the highest per capita water use in all of Los Angeles County. Novick responded by writing an article for the Huffington Post, outing her neighbors for running their sprinklers at full force and arguing that “lawns are a criminal infringement.” She attributes her community’s resistance largely to its affluence, conservatism, and concern about property values. “When I look at a highly manicured lawn that is using pesticides and herbicides when we’re in a water crisis, that announces a person who has her head in a bag,” she said.

Novick’s colleague at Theodore Payne, a longtime horticulturalist named Lili Singer, teaches a course called Look, Ma, No Lawn!, which became tremendously popular as the drought worsened. “I could not schedule enough classes last year,” she told me one Sunday morning at the Hollywood Farmers Market, where she runs Theodore Payne’s “baby nursery” booth. The interest was largely driven by the M.W.D. cash-for-grass rebate, she said. First-time gardeners who could barely tell a poppy from a petunia were arriving en masse, and one devoted alumnus raved that talking to Singer was like talking to God. (When I mentioned this to Singer, she said, “I’m a third-generation atheist.”)

But last summer, the M.W.D. rebate funding ran out, which brought the program to an end. And while southern California remains in a state of “exceptional drought,” conditions improved enough in the northern half of the state that this May, Governor Brown ended mandatory water restrictions, returning authority to local agencies. In Los Angeles, many restrictions remain in place, yet the sense of urgency has waned. “Even with the focus on outdoor water efficiency from the governor on down, and the historic investment in turf rebates, there’s still a huge educational challenge,” Patrick Atwater, who heads the California Data Collaborative, told me. “The message has largely been around turf removal and a general ‘eat your broccoli’ style of conservation.” Homeowners had trouble seeing the possibilities outside prickly cacti. A good portion of the millions issued in rebates wound up going to corporations and golf courses, undermining the program’s neighbor-influence effect. Attendance at Lili Singer’s classes is way down. “I have felt pretty devastated,” she said. “It’s terrible, this idea that you’re only going to come if they’re giving you money.” Southland Sod has rebounded, and Jurgen Gramckow told me that the company is back to 800 acres, an apparent win for the status quo campaign. Even though water agencies spent half a billion dollars on lawn-removal rebates, and even though southern Californians ripped out around 150 million square feet of turf, that was only 1.6 percent of the region’s lawns. A post-grass mentality is still hard to accept.

When Andrew Jackson Downing sought the model of a perfect lawn for his book, he found the Livingston estate near Hudson, New York, where acres of hills were covered in velvety grass. It was only in a letter to a friend that he mentioned maintaining the lawn required the labor of ten men.

In southern California, even with the invention of the power mower, the perfect lawn is made possible only by the work of tens of thousands of Latino immigrant gardeners, many of whom work off the books, for minimum wage, six days a week. They are known as “mow and blows.” (The fathers and sons who mow their own lawns in images of midcentury domestic bliss are now a rare sight.) These gardeners find themselves the primary managers of water use, which sometimes puts them at odds with the demands of their employers, who want to avoid brown spots.

In wealthy Hancock Park, in central Los Angeles, I met Ramon Espinoza, a landscaper from Zacatecas, Mexico, who has run a garden crew in southern California’s chichi neighborhoods for two decades. He was working on a corner property, watching his longtime partner, Álvaro, straddle a branch two stories high while wielding a chain saw. “He’s been working in trees for fifty years,” Espinoza said as we studied Álvaro’s balletic maneuvers.

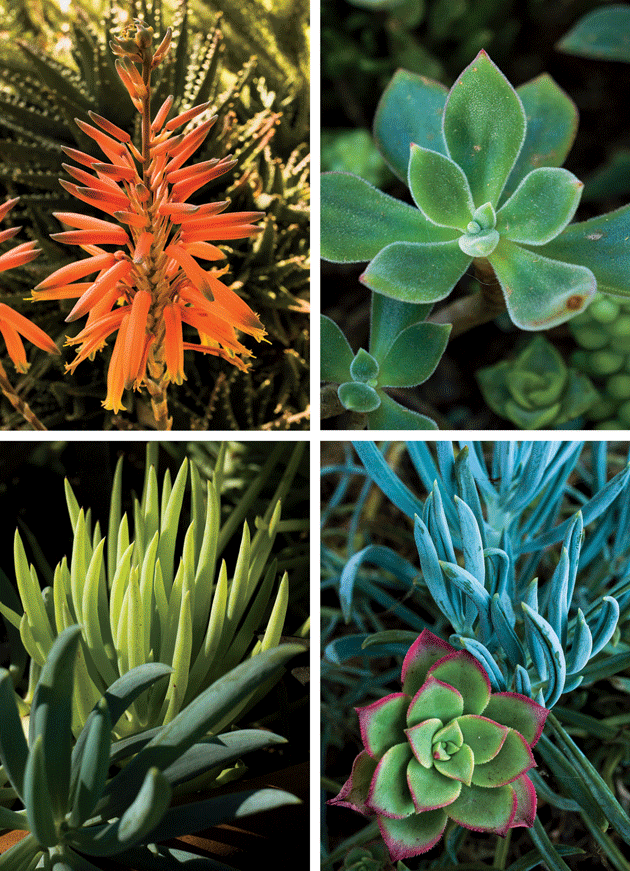

Many residents of Hancock Park have been hiring Espinoza’s crew to remove grass and replace it with desert plants, like cacti and non-native succulents. “They do well,” he said. “You don’t need a lot of water.” When I asked him about California natives, he said that he didn’t know plants by their origins — he just learned the plants that nurseries sold and that his clients wanted. It often seemed that apart from people at the Theodore Payne Foundation, the landscape industry was unfamiliar with the wide variety of native flowers and shrubs.

Espinoza lives in Inglewood, a community with one of the lowest per capita water-usage rates in the county. A UCLA study on residential water consumption in Los Angeles found that Latino households irrigate less than other demographic groups. Espinoza has no sprinklers, and his back yard is covered in a gold-dyed decomposed granite, or DG, which looks like sparkly sand. Some of his neighbors are switching from grass to gravel and pavers. Few fetishize their own lawns. “They don’t worry about water,” he said. “The politicians can worry about that.”

This approach has not been promising. “Angelenos never let a good crisis go to waste,” Eric Garcetti, the mayor of Los Angeles, announced in his 2015 State of the City address. “We’re even using this drought to create jobs. For example, Turf Terminators is an L.A. company that leverages rebates to replace water-guzzling lawns with beautiful, water-wise plants.” Within months, after blighting city yards and replacing lawns with bleak gravel while taking entire rebates as pay, Turf Terminators folded. In May, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power announced the start of a bilingual program to train mow-and-blow gardeners to create and maintain drought-tolerant landscapes, but there have been no signs of classes starting up anytime soon.

One Sunday afternoon, I drove to Laguna Beach to meet Kevin Naughton, who recently closed the nursery that he and his wife had run for thirty-five years. Laguna Beach was originally established as an artists’ colony — something locals like to mention — but it had the misfortune of being built in a gorgeous canyon. Today, it is overrun with millionaires. Naughton belongs to an earlier generation (long hair, Lichtenstein print on his T-shirt), and still works as a landscape contractor. “There’s so much money in this town,” Naughton said, “that people will say, ‘I don’t care, I just want my garden to look good. I’ll pay the fine.’ ”

Lately, even Laguna Beach has pressed its residents harder, with public-education campaigns, rain-barrel giveaways, and hose-nozzle rebates. Naughton offered to show me around a drought-tolerant plant display outside the city’s water-district building. It was almost dusk, and the garden — California natives; Mediterranean herbs; and exotic, sculptural succulents — was enchanting. The succulents, now so trendy that they’re almost passé, were eye-popping to the uninitiated. The blue chalk sticks were a little stunted, haunted even, like alien fingers pointed at the sky. Aeonium arboreum “Zwartkop” was glam punk, Crassula vintage folk, and kangaroo paw outback chic.

We stopped in front of sea lavender, scented geraniums, and several different species of pungent native sage. We both took a sniff. “Sages are my personal favorite,” Naughton said. When he was starting out, he taught himself about native plants by hiking into the hills beyond Laguna Beach to “pick and smell” anything aromatic. He’d stock up, but the finds weren’t especially popular. In those days, he recalled, “No one had any awareness about natives or succulents. Everyone wanted palm trees. You can’t give away a palm now.”

I followed Naughton to the edge of the garden, where there was a small patch of grass next to a koi pond. “I don’t like this,” he said, shaking his head. I realized that the grass was in fact synthetic turf. It looked more real than other fake turf I’d seen. The stuff is made from old tires and plastic, it’s mostly impermeable, it has to be washed, and it gets hotter than asphalt in the summer. At a $25 million house Naughton was working on, his crew was placing it between strips of patio. “I do it when I’m forced to, but I really loathe it. It’s like laying carpet down on the earth.” We watched the koi circling for a moment, and a small turtle popped her head above the surface.

Southern California is filled with people from other places. Many were drawn by images of an earthly paradise, first promulgated by nineteenth-century boosters hawking the land’s Mediterranean climate and new Edenic gardens full of imported exotics. (For the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, developers and railroad companies sent the landscape on tour, packing train cars with palm trees, tropical ornamental plants, and patches of lawn.) Modern transplants are still drawn by the sunshine, mild temperatures, and gardens where anything can grow all year round — as long as there’s water. The idea that they might now have to trade in their green plinth and favorite rosebush for a drought-tolerant landscape is understandably abhorrent.

Some residents seem determined to deny the very existence of the drought. In Bel Air and other hilltop communities, the extravagance is incredible — a parody of unchecked water greed. Maureen Levinson, the minivan vigilante, showed me around one Tuesday afternoon. Enormous houses were under construction, and despite the magnificent view of Santa Monica and the Pacific beyond, it was hard to relax with the incessant noise of jackhammers, groaning cement mixers, and exhaling Jake brakes ricocheting across the canyons. “So over here is a seventy-four-thousand-square-foot home,” Levinson said, pointing at a concrete colossus. The neighbors were saying that the owners might be connected to Qatari royalty. The giant structure next to it, she explained, would be their 20,000-square-foot guest house. “I think they have three pools.” She pointed out several other new houses, in various stages of construction, which also had multiple “water features,” she said. “There’s no pool cover on any of them. This is just to show water flowing.”

In another part of Bel Air, we stopped at an open house. “Look at that lovely view!” Levinson marveled innocently. The plans for the house that would replace the one we stood in were displayed on the walls. As Levinson studied them, a broker gushed about the layered infinity pool that would run the length of the facade and look out over the ocean. Levinson asked about another blue section in the design. “This is a waterfall,” a second broker said. “So you’re looking over water, over water, out to the water.” Levinson gave me a look. “And the guest house will have the same thing?” “That’s exactly right,” the broker said. “A lot of water.” As we left, sprinklers were irrigating the vacant home’s clay tennis courts.

I returned to Hancock Park. It was five o’clock as I turned up Rimpau Boulevard. I rolled my window down: there, for the first time, I spotted a person standing on a lawn who hadn’t been paid to be there. His name was Michael Johnson, and he was walking barefoot, sprinkling his grass with white grains of fertilizer from a ziplock bag. I waved hello and asked how his lawn was doing. Johnson seemed happy to receive the question. “If we get enough rain to dissolve this chemical, it’ll green up nicely,” he said. “Until it dries out again. Then your choice is to pray for more rain or give it water, and that’s when people drive by and go like this,” he said, demonstrating a lively bras d’honneur.

Johnson is sixty-two, AfricanAmerican, and built like a former linebacker. He retired from public relations after twenty-five years; his wife was an editor at the Los Angeles Times. They bought their house, a “seven-bedroom cottage-on-steroids,” twenty years ago, “when it was a dump.” But they brought the place back, and now consider it the best investment they ever made. “It’s all we have,” Johnson said. “Our kids have squandered all of our nest egg.” The property has a wide border of cashmere-leaved herbaceous shrubs. Parts of his lawn had threadbare patches the color of straw, but there were plenty of green blades, too. “Do you like the color palette?” he asked. I did. “See the subtleties in the Brugmansia?” He pointed out their flowering shrubs. “There are people who stop me on the street and ask me about my Brugmansia. But I need to trim it.” There were also Pittosporum tenuifolium “golf ball,” sweet pea, and Eugenia trees. “Want to see the rest?”

I followed Johnson and his fourteen-year-old Labrador retriever, Frank, up the driveway and into the back yard. There was a pool, a patio, a grill, and more patchy lawn. “We just harvested the kumquats,” he said. Some had fallen onto the pool deck, staining it with splashes of orange pulp. He gave me a tour of his succulents and his ficus garden, splashing through little puddles in the lawn left over from sprinklers he’d run earlier. “Grass has always been important for me, from a cultural standpoint,” he explained. When he was six, he moved with his single mother and three siblings from Long Island to South Central Los Angeles. “We lived in rented properties. Always with a little plot. You could have your barbecue, your picnic — just ten square feet, but you could say, ‘That’s my lawn!’ ” Now he was standing in his own resplendent yard, under an olive tree. Johnson’s delight in his garden was contagious, and it suddenly seemed unfair that someone who relishes the grass under his feet should be made to give it up. And yet his generation of southern Californians is likely the last that will enjoy suburban verdure free of guilt and without spending a fortune. In the future, perhaps people will consider expanses of lawn to have been a twentieth-century folly — like smoking on an airplane — with some combination of nostalgia, pity, and envy.

I followed Johnson and his fourteen-year-old Labrador retriever, Frank, up the driveway and into the back yard. There was a pool, a patio, a grill, and more patchy lawn. “We just harvested the kumquats,” he said. Some had fallen onto the pool deck, staining it with splashes of orange pulp. He gave me a tour of his succulents and his ficus garden, splashing through little puddles in the lawn left over from sprinklers he’d run earlier. “Grass has always been important for me, from a cultural standpoint,” he explained. When he was six, he moved with his single mother and three siblings from Long Island to South Central Los Angeles. “We lived in rented properties. Always with a little plot. You could have your barbecue, your picnic — just ten square feet, but you could say, ‘That’s my lawn!’ ” Now he was standing in his own resplendent yard, under an olive tree. Johnson’s delight in his garden was contagious, and it suddenly seemed unfair that someone who relishes the grass under his feet should be made to give it up. And yet his generation of southern Californians is likely the last that will enjoy suburban verdure free of guilt and without spending a fortune. In the future, perhaps people will consider expanses of lawn to have been a twentieth-century folly — like smoking on an airplane — with some combination of nostalgia, pity, and envy.

Johnson grabbed a big recycling bin and wheeled it down the driveway to the street. A hummingbird fluttered in a neighbor’s ficus hedge. Johnson turned back and faced his home. “It was my dream when I was a kid to have a great house with a great lawn,” he said. “Life is ironic. Just when you get that, the whole paradigm changes, and now you have to be responsible for something else. It’s been like, goddamnit, I’m going to have my great lawn. And we just battle it out day to day on the water.”