While tramping through the Daniel Boone National Forest, it is not unusual to come across a family cemetery — stones broken, names faded — or the foundations of a house, or a collapsed chimney. One afternoon I was driving with Johnny Faulkner, an archaeological technician for the forest, down a dirt-and-gravel Forest Service road, pines standing stiff as corpses on either side of us, as if they didn’t yet know they were dead, when suddenly we came upon tidy, shiny clumps of daffodils and the remains of an apple orchard another twenty yards or so into the forest. People had lived here once, cleared the land with axes and mules, built a house and farmed, and some woman who worked as hard as a mule herself had wanted a garden — daffodils and lilies, maybe rose of Sharon, just something pretty to tend. You might come across the remnants of a still — fragments of glass jars, galvanized buckets, crudely constructed beds where the moonshiners would sleep. You might find traces of a niter-mining site, holes drilled into the sandstone during the Civil War, or wooden boards from leaching vats. Or evidence of a Native American hunting camp from thousands of years ago. This is lived-in, worked-over land . . . still.

One morning, I go up in a helicopter from the Civil Air Patrol field in London with men hunting for pot patches. Harold Sizemore, a legendary spotter, rides shotgun. We are rechecking for some pot found the other day, a tiny patch, but they want to show me how an operation might work.

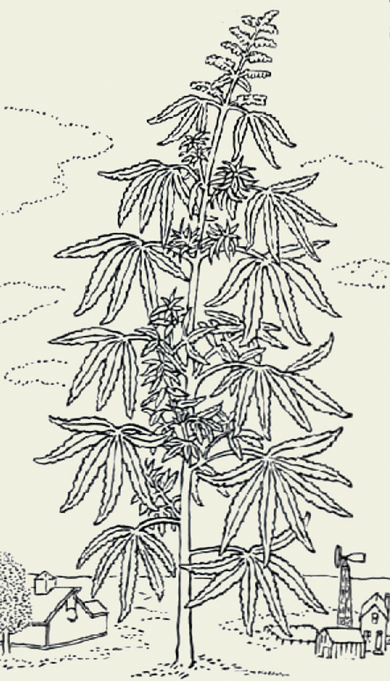

We’re flying over Laurel County, better known for meth labs than for marijuana farms, but that’s where they’ve found a patch that’s close to the road, so when I go in later with some of the drug cops who will eradicate the plants, I won’t have a long hike. Much of the work these units do is arduous: they often trek miles over mountainous terrain to get to a site, or rappel into pot patches from helicopters and chop down the plants. Then they and the plants are lifted out and set down on some plateau, and once the helicopter has landed, they board it again. Sometimes they will do five or six jumps in a day — and all of it in the sticky heat of summer and early fall. The team scans the terrain below. They are looking for things that don’t belong, Harold explains: an odd hole in the forest canopy, a cluster of dead, leafless trees, a peculiar change in the thickness of the foliage, and a particular shade of green — nothing else in the forest is that hue, the drug cops tell me. Bob O’Neill of the Two Rivers Drug Task Force, a High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) team composed of Forest Service agents, national guardsmen, and local law enforcement, says that this green stands out to him as vividly as the orange on a hunter’s vest.

The team scans the terrain below. They are looking for things that don’t belong, Harold explains: an odd hole in the forest canopy, a cluster of dead, leafless trees, a peculiar change in the thickness of the foliage, and a particular shade of green — nothing else in the forest is that hue, the drug cops tell me. Bob O’Neill of the Two Rivers Drug Task Force, a High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) team composed of Forest Service agents, national guardsmen, and local law enforcement, says that this green stands out to him as vividly as the orange on a hunter’s vest.

Marijuana cultivation is the forest crime that has gotten the most attention by far — from the federal government, from the media. Once, people made moonshine in these mountains; now they farm pot, playing the same cat-and-mouse game with the authorities. The counties that produce the most pot are among the poorest in the nation. The Appalachia HIDTA team is considered a highly successful crime-busting unit, but if you add up the amount of marijuana eradicated, the number of meth labs cleaned up, the drug arrests made, and the length of the prison sentences handed out, and compare them to the area’s illiteracy rates (48.4 percent, the highest in the nation), average individual income ($12,000), and morbidity rates (Appalachian Kentucky has the highest death rate in the nation from all cancers), it is clear that the government has fought the drug war and abandoned the people, ensuring that the war never ends.

From “Crimes Against Nature,” which appeared in the July 2008 issue of Harper’s Magazine. The complete essay — along with the magazine’s entire 166-year archive — is available online at harpers.org/fromthearchive.