Ashley arrived for her prenatal appointment at Black Hills Obstetrics and Gynecology, in Rapid City, South Dakota, wearing a black zip-up hoodie and Converse sneakers.* To explain her absence from work that morning — a Tuesday in April 2015 — she had told a co-worker that she was having “female issues.” She was twenty-five years old and eight weeks pregnant. She had been separated from her husband, with whom she had a five-year-old son, for the better part of a year. The guy who’d gotten her pregnant was someone she’d met at the gym, and he’d made it abundantly clear that he wanted nothing more to do with her. Ashley found herself hoping that the doctor would discover some kind of fetal defect, so that her decision would be easier. She glanced across the waiting room at a television playing a birth-control ad and laughed darkly. “Jesus, Lord, it would be so nice if someone just pushed me down a flight of stairs.”

In the exam room, she perched on the table with her feet crossed at the ankles, her blond hair brushing the back of her pink hospital gown. “I don’t know what’s available for me here,” she told her doctor, Katherine Degen, who sat facing her on a stool. “I figured nothing.”

“Big, fat zero, unfortunately,” Degen said, making a 0 with her fingers. The last doctor who provided abortions in Rapid City retired in 1986, three years before Ashley was born.

The baby was due in November, when Ashley, who was a nurse, hoped to be enrolled in a graduate program to become a nurse practitioner. Getting pregnant as a teenager had forced her to put that dream on hold, but she had thought that she was finally ready; she had even submitted her application shortly before the March 15 deadline. For the first time in her adult life, Ashley felt as if her plans were coming together. Then she missed her period.

It would be too difficult to attend school as a single mother of two, Ashley knew. She had made an appointment for three weeks from now at the nearest abortion clinic, in Billings, Montana, 318 miles away. But just a week and a half ago, her husband had said he wanted to get back together and offered to raise the child as his own. Was it a sign that she was meant to continue the pregnancy? As a rule, Ashley approached her problems with resolve. She was capable and tough; she liked shooting guns and lifting weights. She kept track of her stats and checked off her goals as she achieved them one by one. Yet the dilemma before her had shaken her confidence. She leaned back and turned to watch the ultrasound screen. The black-and-white image danced. A sharp, fast thumping emerged from the machine. As Degen removed the wand, Ashley wiped the corner of her eye.

“Whatever you want to do,” Degen told her, “we’re here for you.” She left the room. Ashley stood quietly in her orange socks, looking down at the sonogram she held in her hands.

Later, I asked the doctor how often she saw patients who were considering an abortion. “Once a month, maybe,” Degen answered. “And how many don’t tell us?” She knew patients feared her and her colleagues’ disapproval. Very few of the women, she guessed, ever went through with the procedure.

At eight weeks, four days pregnant, Ashley was still within the recommended ten-week window for mifepristone and misoprostol, pills that are taken in two doses to induce miscarriage. In some states, a medication abortion is easily obtained — even nurses can administer one. But Ashley’s doctor could not offer to write her a prescription, because Black Hills isn’t licensed as an abortion facility.

South Dakota law requires facilities that provide abortions — including medication abortions — to obtain a special license from the Department of Health. Yet for patients like Ashley, the problem isn’t merely that the law makes it hard for doctors to perform the procedure; it is that few in Rapid City would be willing to. Physicians’ right to refuse is legally protected. Since 1973, the state has exempted medical professionals from any liability that might result from such a refusal, regardless of whether a woman is seeking an elective abortion or having a medical emergency.

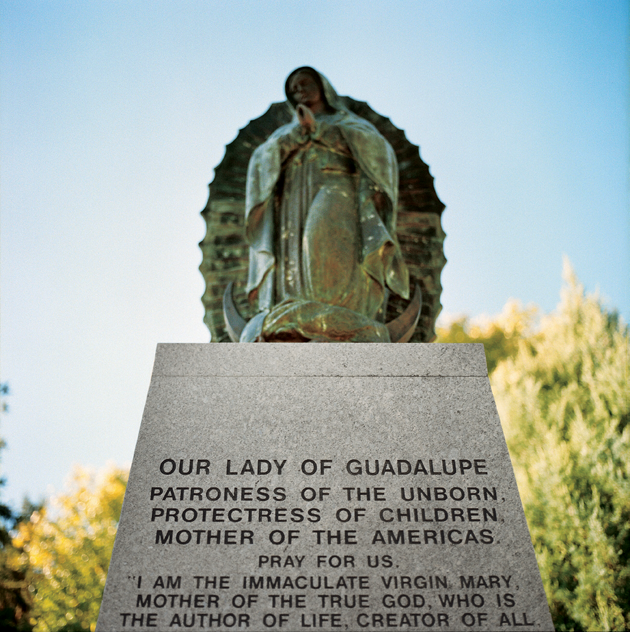

These and other laws make South Dakota among the most difficult places in the United States to end a pregnancy. Lawmakers tried to ban abortion in both 2006 and 2008. The first time, the proposed ban was absolute, except to save the life of the mother; the second time, it made exceptions for rape and incest. Proponents campaigned against “abortion as birth control.” Kate Looby, a former director of Planned Parenthood of South Dakota, remembered the censorious tone of the legislators: “Women, if you’re going to have sex, you’re going to have to deal with the consequences.” Voters rejected both bans by a margin of around 10 percent each time, but new restrictions have been introduced nearly every year since. In 2011, the state mandated a seventy-two-hour waiting period that requires women to make two separate trips to the clinic: first for an initial consultation, and then, three business days later, another for the procedure itself. Regulations compel doctors to tell women that “abortion will terminate the life of a whole, separate, unique, living human being,” that abortion is linked to suicide and depression, and that state funding may exist to cover the cost of prenatal care and childbirth. Women must be told the gestational age of the fetus and what it looks like.

These and other laws make South Dakota among the most difficult places in the United States to end a pregnancy. Lawmakers tried to ban abortion in both 2006 and 2008. The first time, the proposed ban was absolute, except to save the life of the mother; the second time, it made exceptions for rape and incest. Proponents campaigned against “abortion as birth control.” Kate Looby, a former director of Planned Parenthood of South Dakota, remembered the censorious tone of the legislators: “Women, if you’re going to have sex, you’re going to have to deal with the consequences.” Voters rejected both bans by a margin of around 10 percent each time, but new restrictions have been introduced nearly every year since. In 2011, the state mandated a seventy-two-hour waiting period that requires women to make two separate trips to the clinic: first for an initial consultation, and then, three business days later, another for the procedure itself. Regulations compel doctors to tell women that “abortion will terminate the life of a whole, separate, unique, living human being,” that abortion is linked to suicide and depression, and that state funding may exist to cover the cost of prenatal care and childbirth. Women must be told the gestational age of the fetus and what it looks like.

Also in 2011, legislators passed a bill that forces women to visit a crisis pregnancy center in addition to making the two trips to the clinic. C.P.C.’s, which are run by antiabortion groups, often discourage the use of contraceptives, and are known for such underhanded tactics as telling women that abortion is linked to breast cancer and infertility. That bill is currently stayed by a district court, but in March 2016, South Dakota passed two additional laws. One mandates that women receiving medication abortions be told — erroneously — that the procedure is reversible if they change their minds between the first and second doses. The other prohibits abortions at or beyond twenty weeks — meaning that a woman who discovers too late that she is carrying a nonviable fetus must wait for it either to expire in utero or to die after birth.

Largely rural and sparsely inhabited, South Dakota has two main population centers: Rapid City, in the west, and Sioux Falls, in the east. They feel like separate states; each is in a different time zone. “West River,” as South Dakotans call the region Ashley comes from, west of the Missouri River, is the more conservative. The major industries are cattle ranching and mining. Most residents are religious — the assumption is that you’re a Christian. At Rapid City’s Rushmore Mall, Sunday services are held at Hills of Grace Fellowship, next door to MasterCuts and around the corner from Hot Topic. Things here tend to stay the same. Families can trace their roots back three or four generations. Some residents never leave their zip code.

People living in Rapid City must travel farther to reach an abortion provider than residents of any other place in the nation. The lone abortion clinic in the state is the Planned Parenthood in Sioux Falls, 350 miles away, in South Dakota’s more progressive southeastern corner. I-90, the main thoroughfare between the two cities, is frequently closed during the winter because of snow and ice. A few years ago, when a blizzard hit, dead and bloated cattle lined the highway. All the Planned Parenthood doctors fly in from out of state, and patients are required to see the same person for both their appointments, so if a doctor’s plane is canceled or the highway is closed on any leg of the trip, the process has to begin all over again. “Most people make the trip on Monday and have their visit and turn around and drive right back,” explained the clinic manager. “And the same thing on Thursday.”

Once South Dakota’s waiting-period law went into effect, the Red River Women’s Clinic, in Fargo, North Dakota, began seeing an increase in patients crossing the border. Red River is the only abortion provider in North Dakota, and in fact the same few doctors serve the whole region, flying from Minneapolis to Fargo, Sioux Falls, and a few other cities on a rotating schedule.

The cost of the abortion, the cost of transportation, the cost of childcare, missed work, an overnight stay, a possible delay because of snow or ice — these are among the burdens women in South Dakota must bear when they seek a medical procedure that is now regulated unlike any other. But the law is not the only source of the pressure that women experience: the bounds of what is culturally acceptable are also narrowing. In Rapid City, even pro-choice activists seemed nervous when I spoke too frankly in public. “Watch the a-bombs,” one woman whispered to me in a restaurant.

Ashley grew up in a former mining town in the Black Hills. Her high-school class, which graduated in 2008, had fewer than eighty students. Sex education was limited; the assumption was that kids would learn what they needed to know at home. Ashley’s family attended mass every Sunday, and her parents counseled abstinence until marriage. But students nonetheless tended to become sexually active in early high school. Ashley and her friends would get together for “cackling-hen talk,” as she called it, about what the guys were doing to impress them when they “went all the way.” She guessed that at least five girls in her class were pregnant before they turned twenty.

Ashley grew up in a former mining town in the Black Hills. Her high-school class, which graduated in 2008, had fewer than eighty students. Sex education was limited; the assumption was that kids would learn what they needed to know at home. Ashley’s family attended mass every Sunday, and her parents counseled abstinence until marriage. But students nonetheless tended to become sexually active in early high school. Ashley and her friends would get together for “cackling-hen talk,” as she called it, about what the guys were doing to impress them when they “went all the way.” She guessed that at least five girls in her class were pregnant before they turned twenty.

In college, Ashley met Peter at a fraternity party, in a dark, smoke-filled basement. A year after they started dating, Ashley discovered she was pregnant. She was nineteen. Her sophomore year had barely begun. She and Peter got along well, but they weren’t in love. She had wanted to travel the world in her twenties, not start a family in her teens, yet the path seemed clear. “We’re definitely keeping it, right?” Peter said when Ashley broke the news. Both of them came from Christian families and they were raised to know right from wrong. It was 2009, the year after South Dakota’s second attempt to ban abortion. Ashley had seen the pro-life ads, read the op-eds by pro-life pediatricians, witnessed the heated demonstrations. The fervor helped reinforce what was acceptable and what wasn’t. At her wedding, she was twenty-one weeks pregnant.

Ashley stayed in college, but pregnancy ended her career on the cross-country team and wrecked her athlete’s body. And while she loved being a parent, she sometimes felt that she had no life outside her roles as a wife and mother. These feelings began to change in 2013, when she took up weight lifting. On social media, she documented her changing body and growing sense of autonomy. In one video, she looks off into the distance, takes a deep breath, and deadlifts more than her body weight.

Ashley considered herself an independent thinker; she believed that women who faced unwanted pregnancies should be able to do whatever best suited them. But now that she was pregnant again, none of her options seemed good. She already had one child, so pregnancy was not an abstraction; she couldn’t avoid imagining the fetus as the beginnings of a specific person rather than as a collection of cells. At the same time, she knew that if she kept the baby, her parents would be terribly disappointed in her. The child would be born out of wedlock, and Ashley worried they wouldn’t love it as much as her first. The “sperm donor,” as Ashley called him, was half black, and in all likelihood she would be the mother of a noticeably biracial baby in an overwhelmingly white city. Ashley knew that her husband wouldn’t be seen as the “real” dad — he was “as white as the day is long.” She imagined herself as the maid of honor at her sister’s wedding that fall, seven months pregnant with another man’s child.

The logistics were yet another consideration. She would need to be gone for at least a day and a night. Who would watch Ashley’s son if not her parents? How could she explain needing to leave town on a Wednesday, the only day the Billings clinic could schedule her surgical abortion?

Ashley’s close friends were mothers, and asking for their support — emotional or material — would be asking them to aid in what was, to them, a moral wrong. “They would say abortion is murder,” Ashley explained. “Or selfishness on the mom’s part. Like, ‘Well, you should’ve kept your legs shut, then.’ ”

The obstacles encountered by women seeking abortions in South Dakota are not unique to that state. Five states — South Dakota, North Dakota, Missouri, Kentucky, and Mississippi — have just a single clinic left. Fourteen states demand waiting periods that necessitate two trips to the clinic. Nineteen ask abortion providers to have a relationship with a local hospital that includes admitting privileges (which are often denied, especially in conservative areas) or an emergency-transfer agreement. Twenty-one require clinics to make expensive, unnecessary upgrades that effectively transform them into mini-hospitals. A state can restrict a woman’s insurance from covering an abortion or force her to view a sonogram; it can require a teenager to seek permission from her parents. Stiff regulations have become the rule, not the exception.

How did we get here? Most of the current restrictions owe their existence to a standard that was established by the Supreme Court in 1992, in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion in 1973, had prohibited states from impeding access to the procedure before fetal viability (now understood to be around twenty-four weeks). In a landmark shift, Casey established that the state had an “interest in potential life” from conception and could attempt to persuade women against abortion by expressing a “preference for childbirth.” The only laws that Casey forbade were those whose “purpose or effect is to place substantial obstacles in the path of a woman seeking an abortion.” The decision permitted legislation that claimed to serve women’s health. It allowed states to restrict abortion so long as the measures did not impose an “undue burden” on women. What that meant, exactly — what qualified a burden as undue — has been a political and legal point of contention ever since.

How did we get here? Most of the current restrictions owe their existence to a standard that was established by the Supreme Court in 1992, in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion in 1973, had prohibited states from impeding access to the procedure before fetal viability (now understood to be around twenty-four weeks). In a landmark shift, Casey established that the state had an “interest in potential life” from conception and could attempt to persuade women against abortion by expressing a “preference for childbirth.” The only laws that Casey forbade were those whose “purpose or effect is to place substantial obstacles in the path of a woman seeking an abortion.” The decision permitted legislation that claimed to serve women’s health. It allowed states to restrict abortion so long as the measures did not impose an “undue burden” on women. What that meant, exactly — what qualified a burden as undue — has been a political and legal point of contention ever since.

After Casey, the antiabortion movement adopted an incremental strategy. Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, as federal rulings progressively narrowed the definition of “undue,” legislators successfully passed restrictions in state after state. In 2007, the Supreme Court upheld a Nebraska ban on so-called partial-birth abortions and reaffirmed the undue-burden standard. The ruling energized the antiabortion movement. When Republicans swept state legislatures and governors’ races in 2010, antiabortion activists seized the moment. According to the Guttmacher Institute, between 2011 and 2013 thirty states passed no fewer than 200 abortion restrictions — more than the total number passed across the country in the previous decade.

On the other side of the state from Ashley, in a small bungalow on a tree-lined street in Sioux Falls, Ann and Evelyn Griesse’s phone rings upwards of ten times a day. This residential number is the line for South Dakota Access for Every Woman, a fund that helps women cover the cost of abortions; it also serves women in North Dakota, Iowa, Nebraska, and Minnesota. “Please do not call at night,” the fund’s website implores.

Ann and Evelyn are sisters in their seventies. Ann, who generally handles the calls, is a retired librarian; Evelyn, a retired physical therapist, still works three or four days a week as a nurse’s aide at Sanford Hospital in order to finance the project. The two are the primary donors to the fund.

Evelyn walks with a slight shuffle. She keeps her hair in a bun and wears wire-rimmed glasses. At the hospital cafeteria, she sprinkled Fritos over her split-pea soup and told me about her experience obtaining an abortion as a young woman in the early 1970s, before Roe. “I didn’t know who the dad was,” she said. “And I didn’t care.” She flew from South Dakota to a clinic in New York — not a difficult trip if you had the money, but impossible if you didn’t. Later, she began to feel that she owed it to women with fewer resources to help them.

The Griesses’ callers are young and pregnant, old and pregnant, jobless and pregnant, pregnant in high school, pregnant after getting laid off, pregnant by an abusive partner, pregnant from rape or incest — pregnant under all the many conditions that can prevent women from accommodating a child in their lives. Some must take drastic measures to reach the nearest abortion clinic. “If you’ve got something to sell, you sell it,” Evelyn said.

She shuffled a stack of papers. They were notes from interviews with abortion-fund applicants. “Here’s a domestic-violence situation,” she said. She read the cursive handwriting. The woman was a full-time cosmetology student with a ten-month-old child. Her abusive partner would not help pay for the abortion. The clinic fee, after a discount, was $490.

Callers often wanted reassurance. “You’re making the best choice that you can for your life and the kids you’ve got now or the ones you’re hoping to have in the future,” Evelyn told them. “Even if you don’t have kids, you’re still a family. I think of one person,” said Evelyn, who is unmarried. “That’s a family.”

In 2014, the Griesses disbursed $20,820.40 to 104 women (around one third of the callers). Close to half of the women they help already have children. The Griesses cannot cover the entire cost of an abortion, but they chip in between $100 and $300. In 2015, the money ran low, and the sisters gave out just $7,291 to sixty-three callers. They frequently referred applicants to other abortion funds, many of which are also overburdened.

When women called from South Dakota, Evelyn told them about the seventy-two-hour waiting period. “If you can make it to Fargo, if you can make it down to the Omaha area, if you can get over to Wyoming or Colorado,” Evelyn advised, “do it.” But she had noticed a curious development: these days, hardly any of the callers were from South Dakota.

Ben Munson was the last abortion provider in the West River region. He began offering abortions at his ob-gyn clinic in Rapid City in 1967, before they were legalized, and continued doing so until 1986, when he retired at the age of seventy. (He died in 2003.) Protesters were a near-constant presence outside his practice. “He didn’t come up in polite conversation,” remembered Marvin Buehner, a colleague of Katherine Degen’s at the Black Hills clinic. But Munson didn’t care what anybody thought of him, people said.

After Munson retired, no one picked up where he left off. That made Buck Williams, in Sioux Falls, the only abortion provider in the state. Even in more liberal eastern South Dakota, Williams faced resistance. Every day, he had to walk through a crowd of protesters to get to work. His clinic lost its lease; a laundry service refused its business; antiabortion activists called his staff at home, and at one point distributed pictures of decapitated fetuses to their neighbors. After receiving death threats, Williams began wearing a bulletproof vest to work. “You are the town abortionist,” he told the Washington Post in 1990. “This is not an easy way to practice ob-gyn.”

When Williams retired, in 1994, Planned Parenthood replaced him as the city’s abortion provider, and South Dakota joined North Dakota and other Midwestern states in needing to fly its abortion doctors in from out of town.

This pattern is all too familiar. Many abortion providers had been inspired in the pre-Roe years by seeing “the wards” — the hospital wings devoted to women who had suffered botched abortions, illegal or self-inflicted. In the decades that followed Roe, they began aging and retiring. The next generation lacked the same sense of urgency. Many ob-gyn programs made abortion training optional or stopped providing it altogether. Hospitals ceased performing elective abortions, out of fear for their reputations and the desire to avoid being labeled “abortion mills.” This was especially true in rural areas, where the number of medical centers accepting abortion patients dropped 51 percent between 1977 and 1988. Doctors willing to perform the procedure faced constant protests, threatening phone calls at night, and a real danger of assassination.

“Getting doctors is the number-one problem everywhere,” Alexander Sanger, the president of Planned Parenthood of New York City, told the New York Times in 1992. The restrictive laws that have swept the country since then have exacerbated long-standing issues of access. Today, many secular hospitals are merging with tax-exempt religiously affiliated facilities, many of which refuse to do abortions even in cases of nonviable fetuses. In a Catholic hospital, the termination of a fetus without a brain, for example, is still deemed an elective procedure.

The Black Hills clinic is across the street from a soaring Catholic cathedral, where churchgoers reportedly were once urged to boycott the practice because Marvin Buehner had voiced opposition to South Dakota’s attempts to ban abortion. No one in the building performs elective abortions, yet protesters still visit, carrying signs that proclaim real doctors don’t kill babies. Buehner explained that adding surgical or medication abortion to the clinic’s list of services would make it difficult to provide any other services and possibly jeopardize the practice. Women seeking a Pap smear or an IUD insertion don’t want to have to brave throngs of screaming protesters.

Another local ob-gyn said that the mere fact that she was pro-choice would be enough to prevent other doctors, if they knew, from referring patients to her.

The figure that the Planned Parenthood in Billings quoted Ashley for a first-trimester surgical abortion was daunting: $1,000 out of pocket. Like most insurers, Ashley’s employer-provided plan wouldn’t cover the procedure. Ashley figured that she would need another couple hundred dollars for gas, meals, and a night in a hotel, as the clinic advised her not to drive herself home after the procedure. All told, the trip to Billings would wipe out her savings.

Even so, with her steady job, Ashley would make do. Other women in the state were in worse straits. The two poorest counties in the nation are in western South Dakota. For struggling South Dakotans, most health care — not just abortion — is out of reach. “I have patients that show up for their OB appointments only when they have gas money, or when they can find some family member with a car,” Buehner told me. “They’re not going to come up with a thousand dollars to make two trips and get an abortion in Sioux Falls.” What’s more, poor women usually have to spend weeks or months gathering the money. This delay pushes an abortion to later stages of pregnancy, when the price is higher.

Poor women find it difficult to afford birth control as well. The most effective forms — for example, IUDs and the Pill — are also the most expensive. Condoms are cheaper, but just 82 percent effective with typical use. Plus, South Dakota schools teach abstinence in sex education. The state makes it “really easy to get pregnant and stay pregnant and have a child,” Katherine Degen explained. “They make it very difficult for any other option.”

The cost of raising a child over a lifetime, of course, is far more than the cost of abortion or birth control. But immediate expenses trump those that accrue over the long term, and having children qualifies women for financial assistance that they wouldn’t receive otherwise. South Dakota is one of nineteen states that still haven’t expanded Medicaid. The working poor are stuck in a coverage gap: they earn too much to qualify for Medicaid and too little to qualify for Affordable Care Act subsidies. Few get insurance from an employer. Once a woman is pregnant, however, she can receive Medicaid even if her household income is above the federal poverty limit. In this way, more than a third of births in the state are covered by the federal program. By contrast, there is no money available to subsidize ending a pregnancy; the Hyde Amendment, which has been on the books since 1976, restricts the use of federal funds for abortions.

Some women take matters into their own hands. Not long after South Dakota’s second attempt to ban abortion, in 2008, a pregnant Native American girl, still in her teens, arrived in Buehner’s office, her uterus perforated with a toothpick. Because the risk of infection posed a medical emergency, Buehner was able to perform what Rapid City Regional Hospital deemed a medically necessary abortion, which has a different legal status from an elective abortion (and is thus exempt from the seventy-two-hour waiting period and other restrictions). “That’s how desperate people are,” he said. “There’s going to be more of that.”

Yet many women don’t even raise the subject of abortion with their health-care providers. Karen Pettigrew, a nurse midwife who recently retired from her job at a community health center in Rapid City, where she worked with low-income patients, described the sense of resignation that she frequently observed. “They’re not feeling in control of themselves or their future, and they don’t have a plan, so this” — pregnancy, childbirth — “is just one of the many things that happens to them.” The poverty that contributes to such feelings is even more pronounced on South Dakota’s Native American reservations, where unemployment can reach 80 percent. Native Americans receive health insurance through the Indian Health Service, which is a federal program; none of its funds can be used for abortions. “Everyone just has their babies,” said Chas Jewett, a Lakota activist who works on environmental and reproductive issues.

Ashley’s doctor took a similar view. “I think, here, women are just more —” Degen paused. “I don’t know if ‘defeated’ is the right word, but they kind of accept that this is how it is.”

A few days after Ashley’s prenatal appointment, I met M. B. Nielsen, a nurse midwife who works at a women’s clinic on the Pine Ridge reservation. Born and bred in South Dakota, she has worked with women throughout the West River region. After dinner, we headed to a dive bar called the Brass Rail. As we drove through the wide, shady streets of Rapid City’s historic district, where the doctors and lawyers live, Nielsen’s phone rang. The caller was a woman who wanted to know about medication abortion. Nielsen laughed. “In Rapid City? Do you know where you live?” The woman said she hoped that her family doctor could give her the pills. “I would eat my hat if she did that,” Nielsen said. “But you can try.”

The woman asked about herbs, and Nielsen told her what she tells everyone who asks: you can bleed to death that way. The woman begged for assistance in inducing a miscarriage, at home where no one would see her. Gently, Nielsen said that she’d go to jail if she helped. Although nurse midwives and nurse practitioners in South Dakota can prescribe medication, it’s illegal for them to participate in abortions, even when collaborating with a physician. (Nielsen would not in fact risk arrest, but she could lose her license.)

The woman said that she would do anything to avoid traveling to Denver. She was terrified that someone might see her there, that word would somehow get back to people she knew in Rapid City.

After hanging up, Nielsen explained that the caller’s business could lose half its clients if anyone found out. Nielsen, who has had two abortions and used to have her own home-birth practice, faced a similar reality. If anyone had discovered her history, she, too, would have lost clients.

The day after I saw Nielsen, Ashley and I met for lunch at a coffee shop in downtown Rapid City, an area hardly bigger than four square blocks. We ate outside at a small table. The Black Hills loomed in the distance.

Ashley had a picture of the sonogram on her phone and looked at it periodically. When her husband saw the image, Ashley said, “He was like, ‘Well, we have to keep it!’ ” She laughed. “What is this ‘we’ business?”

She wasn’t sure that he understood what was at stake. “Are you prepared to have your family maybe hate me?” she asked him. “Or your friends? Are you prepared for that?” Peter was confident that he’d love this child as much as their son, but Ashley had her doubts. What if he backed out when the time came?

She wished that they could have a fresh start, without a pregnancy on top of everything else. “We were rocky as it is,” she said, trailing off. “I don’t know.” The phrase was a refrain throughout our meal. She pronounced “know” in the South Dakota way, long, the vowel like the soft double o in “book.”

Her son could tell something was up. When he asked what was wrong, Ashley reassured him that she had just been thinking. “You’ve been thinking a lot lately,” the boy observed.

Before Ashley and Peter reconciled, the decision had seemed clear-cut: she simply couldn’t raise a second child without a co-parent. But now she felt that she needed something that would tip the scales in one direction or another. She hoped that admission to grad school might help her decide. “If I found out I was in, it would give me another excuse to be like, ‘Oh, this really isn’t a good time for me,’ ” Ashley explained. But it would be another few weeks, maybe longer, before she would hear back.

Ashley told me that she’d rather face just about any other medical predicament than this one — even an S.T.D. such as chlamydia or gonorrhea. Her lunch break was drawing to a close. She turned to me. “Do you ever have those moments in life where you wish you could just un-insert a penis from yourself?”

For years, federal appeals courts were split on how to apply Casey’s undue-burden standard. Did the state have to prove that a law protected women’s health? Or did abortion providers have to prove that restrictions created “substantial obstacles” for women? Where did the burden of proof lie?

These questions came to a head most recently in Texas, in a series of appeals that caught national attention. Twenty-three of the state’s forty-one abortion clinics were forced to close as courts upheld a 2013 law that required doctors to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital and clinics to meet the same standards as ambulatory surgical centers. The long travel times that would result from clinic closures, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled, were not prohibitive. Under this interpretation of the undue-burden standard, the state had tremendous leeway to pass further laws that purported to serve the well-being of women, and no obligation to show how they would do so.

In June 2016, in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, the Supreme Court struck down parts of the Texas statute. The majority ruled that the law increased the obstacles faced by women seeking abortions and didn’t provide any health benefits, or none that withstood “meaningful scrutiny.” The decision clarified how the undue-burden test should be applied by the courts, explained Maya Manian, a professor of constitutional law at the University of San Francisco. The state would no longer be able to assert that legislation protected women’s health without providing evidence to back up that claim. Although the ruling was a victory for the pro-choice movement, its effects may take a long time to be felt. Outside Texas, similar laws targeting abortion clinics will need to be challenged and struck down individually.

Of the twenty-three clinics that closed in Texas, some might never reopen; others could take years to get recertified under the state’s onerous licensure procedures. Days after the Whole Woman’s Health ruling, new abortion restrictions went into effect in four states, including South Dakota.

In the three weeks between Ashley’s prenatal appointment in Rapid City and her abortion appointment in Montana, she became more and more attached to the jelly bean, as she had taken to calling it. Her husband’s excitement over the prospect of a second child grew, too. Ashley, Peter, and their son spent Mother’s Day at her parents’ house, making snowmen.

Ashley’s abortion was scheduled for ten o’clock on the morning of Wednesday, May 13. That day, she went instead to the YMCA in Rapid City to lift weights. A few days before, she had squatted a personal record.

If she had gone through with the abortion, she would have set out for Billings before dawn. She would have driven alone for five hours. She would have spent another five hours at a clinic two states away, where all the faces were those of strangers. She would have had surgery with no one by her side to hold her hand.

The idea made her profoundly sad. That evening, she told me on the phone that she was glad she didn’t go through with it. But when I asked what she would have done, a few weeks before, if her doctor had offered her prescriptions for mifepristone and misoprostol, she allowed that she might have chosen differently. “If she just offered something right there,” Ashley said, “ ‘You don’t have to go here to get it, you don’t have to go do something’ — I would have definitely either given it some serious thought or just taken her up on it while I had the balls.” It angered her that so few alternatives existed in the state. Like most West River women, she had assumed before she got pregnant that she could get any medical procedure she needed in Rapid City. “I guess in a way it makes me feel fortunate I at least had the option.”

But did she really have the option? As all women must, she made a decision that was governed by her circumstances. In the end, she felt that she couldn’t travel to Billings. “I for sure would have some form of guilt for the rest of my life,” she said. She laughed in a way that made it clear the subject was painful. “Ending a heartbeat. I just didn’t think I could mentally handle that.”

When she and Peter told her family about the pregnancy, they simply said that they were having a son. They were hoping that the father’s genes would prove to be recessive.

In June, Ashley learned that more than a hundred people had applied to the nurse-practitioner program; only twenty were admitted. She was not among them. The news came as a blow, but she accepted it.

Ashley’s family would soon outgrow its two-bedroom duplex. She and her husband looked for a bigger house in Rapid City. Her mom was thrilled that the couple were back together, Ashley said. She had been concerned about her daughter’s prospects of “finding another man.” A woman needed a husband; now everything was as it should be.

Ashley gave birth to a healthy baby boy on a cold Thursday in November 2015. The same night, the first snowstorm of the season hit South Dakota, grounding flights across the Midwest. As fall turned to winter, Ashley shoveled snow for exercise and, when she could, took the baby to the gym, where she rocked him beside the weight-lifting bench. Sometimes she thought longingly of the number of pounds she used to be able to lift, or wished she were in grad school. But more often she felt good about how her priorities were changing. Her son had been the best thing she had done with her life, and now she had another. In May, her firstborn finished kindergarten. Ashley was glad, she told me, to be raising her family in the place where she belonged.

In summer, Rapid City fills with families on vacation, many of them headed to Mount Rushmore, a half hour away. this baby is a blessing, read a billboard I saw for adoption services. A flyer in the window of a Catholic bookstore advertised Rachel’s Vineyard, a retreat for those facing “the emotional or spiritual pain of an abortion.” Around the corner, in E’Lan’s Vintage Boutique, E’Lan LaBeau, the owner, and her friend JJ Shultz grew thoughtful when I asked them about their views. Both are natives of Rapid City, and they remembered a number of high-school classmates who’d gotten pregnant.

“Most girls just buck up and take it,” Shultz said.

“But that’s their choice,” LaBeau replied.

“But it’s not a choice,” Shultz said. “Not here.”