Seldom can major national news be distilled to a single boneheaded decision, particularly one that poisoned a city. This circumstance alone could determine a narrative of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. Yet when I arrived there on a Sunday afternoon last spring, I found myself driving the city’s grid, trying to find a certain house that might reveal some historical explanation. This is the city where I was born, and I know of a larger story.

My destination was not much of a house, not even when it was new, just one cracker box among many in the old neighborhood of Mott Park. A few blocks northwest of downtown, Mott Park was designed in the Twenties as a workers’ paradise: each street curbed and sidewalked, a bungalow in every lot, patches of lawn to mow, and trees that yielded leaves for raking. Returning after sixty-five years, I noticed first the empty spaces, like gaps in a hockey player’s grin. Flint’s main public-works project these days is razing a thousand houses a year, a number limited only by available funds. The supply of abandoned houses delivered by the collapse of the auto industry, the financial crisis, and now poisoned water has, at least, created work for bulldozers. Most of the houses not yet razed are falling in or filled with trash, or have been gutted by fire. Some have been boarded up against squatters, but hardly any people remain here, in this treacherous part of a city routinely ranked among the most dangerous in the country.

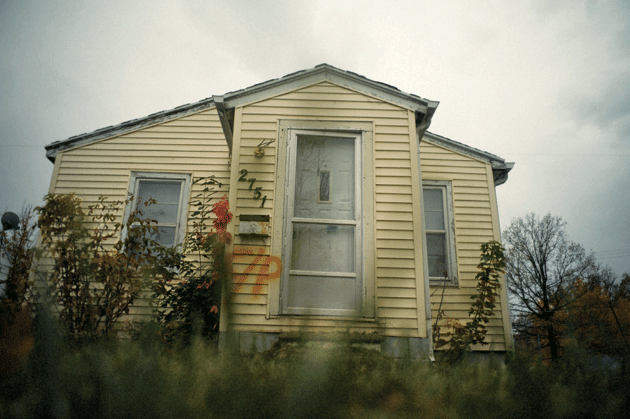

Against the odds, as I turned onto Raskob Street (named for John J. Raskob, a board member of General Motors) I found that the house I was seeking, number 2751, still stood. Barely. The roof had sagged. The siding was painted yellow — in Flint, the color of dirty water and denial. Someone had fastened a thick steel hasp to the front door and padlocked it, but the back door’s window was broken in a way that would allow an arm to reach the dead bolt inside. It seemed to suggest that I enter. As I approached the concrete stoop, shards of glass ground beneath my boots. But I couldn’t go in. I couldn’t find the will to ascend the steps that I had climbed as a toddler. This was my first home, but it had been many years, and it wouldn’t be safe to trespass, I reasoned. So I backed off, snapped a photo, and drove away.

My reckoning of what happened in Flint really begins with another photo, taken on July 4, 1942. My grandparents are in standard American Gothic pose, flanked by a neat, stair-step line of four skinny young boys in fedoras and suspenders. The backdrop is their farmhouse, which stood and still stands a couple of hundred miles north of Flint, on Manning Hill. Within ten years, all four of those boys would be working in Flint, mostly in construction. The photo does not show my aunt, already in Flint by then, working at a defense plant. It does not show the tin shack a mile away, where my mother lived with no plumbing, nor her father and two brothers, who within a couple of years would be shop rats in Flint, and continue as auto workers their whole careers. Most critically, it does not show the four of my paternal grandmother’s ten children who died as children.

The best explanation I have found for the connection between this photo and the one I shot on Raskob Street last spring appears in a recent book, Robert Gordon’s The Rise and Fall of American Growth. Over some 800 pages of exhaustive fiscal and demographic analysis, Gordon, an economist at Northwestern, argues that the boom during the middle of the twentieth century, which created much of what we still think of as the American dream, was a one-shot deal, an unprecedented and since-unequaled anomaly that spanned the dates on the picture at my grandfather’s farm and my own high-school graduation photo, taken several miles away in 1969. These dates mark the period when innovation made the whole country thrive. Then the dream of shared prosperity died. It’s over. If you think otherwise, ask Flint.

Flint’s pain is the result of so many different failures,” Donald Trump said when he visited the city’s Bethel United Methodist Church in September. “The damage can be corrected and it can be corrected by people that know what they’re doing. Unfortunately, the people that caused this tremendous problem had no clue.” This reasoning — which was correct insofar as it was broad and empty — was largely overshadowed by Trump ridiculing the pastor who had invited him to speak. A deeper explanation of who gets the blame for poisoning Flint would mention the Republican governor, Rick Snyder, who placed the city under emergency management, a provision in Michigan law that allows governors to step over bankrupt local governments and impose state rule. In Michigan, bankrupt cities are mostly poor and black, as are a good number of the congregants at Bethel United. To save money, the city’s emergency management decided to switch the drinking-water source from Lake Huron to the Flint River.

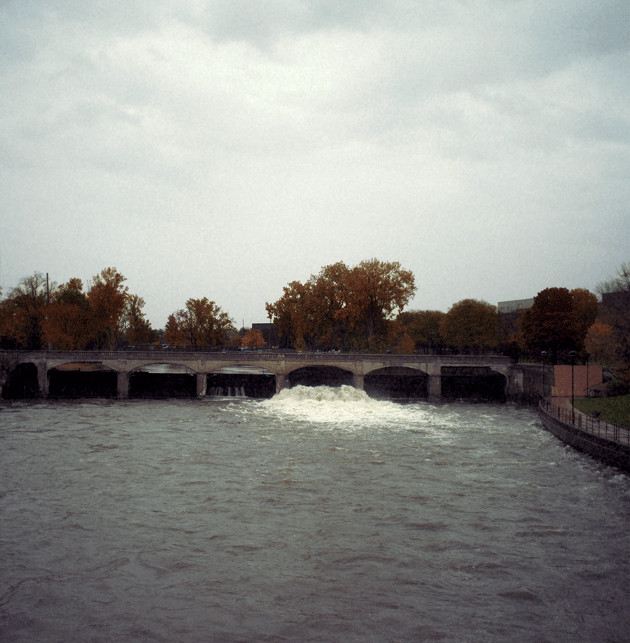

There is nothing especially wrong with the Flint River, which wends through the farmlands and suburbs of Lapeer and Genesee Counties, downtown Flint, and the Shiawassee National Wildlife Refuge before dribbling into Lake Huron’s Saginaw Bay. Yes, the river did take more than its fair share of industrial pollutants when GM workers were busy building cars in Flint’s factories. But the 1972 Clean Water Act was aimed at places like this, and it has remedied the worst of the rust belt’s waste, leaving the Flint River relatively innocuous. The most troublesome pollutants today are pesticides and fertilizers from farms, suburban lawns, and golf courses, as is the case with most rivers across the nation. Kayakers celebrate the Flint River’s cleanliness by paddling away from the edge of downtown, and bald eagles nest along its banks.

In a roundabout way, however, water from the Flint River is toxic because of our devotion to automobiles. My first car was a 1960 Corvair, which my maternal grandfather had a hand in building at the Fisher body plant. When it rolled off the line he tracked it to Applegate Chevrolet, a few blocks away, and bought it. The car was pretty well spent when I paid him a hundred dollars for it, six years later. Friends helped me break it in half within a few months, simply by piling in five or six passengers. By then the Corvair was so badly rusted that it folded under the load. All cars in Michigan rusted out within four or so years, a fact that we earnestly believed was traceable to obsolescence planned by the auto industry and executed by Governor George Romney, a former auto executive. The working hypothesis was that Romney personally ordered his highway guys to spread more salt so that the car guys could sell more cars. This conspiracy theory is not provable, but it deserves some credence, because the practice of salting roads to remove ice, now widespread in the northern states, began in Detroit in 1940.

Like everything automotive, chloride from road salt became layered in Michigan’s geology. As salt runoff flowed from expressways to ditches to creeks over seven decades, finding its way to the Flint River, the water became corrosive — less so than Mountain Dew, but still corrosive. We call the corrosion of metal “rust,” and any water-plant operator worth his paycheck understands how this works. Municipal water plants routinely neutralize the corrosion of pipes with high-school chemistry, usually by adding a bit of orthophosphate, which is cheap and harmless.

Underground water pipes form a narrative of a town’s history, capturing in variously aged segments the patches and workarounds of infrastructure. Each part represents what was available, affordable, and considered a good idea at the time. City water systems — usually made from steel, zinc, copper, and lead — are all corruptible to some degree. But lead is our focus here, because it poisons people. Some of the earliest pipes are pure lead; others, mainly copper pipes, used lead as a part of the solder. In normal systems (to the extent that there is such a thing), most of the lead stays put, wrapped in a coat of oxidized metals that builds up between water and pipe, but corrosive water breaks down that coating, allowing the lead to make its way to taps.

When routine tests showed corrosion, plant operators in Flint did not treat the city’s water. State regulators counseled that they should instead monitor the pipes for six months to see what could possibly go wrong. After GM noticed that water was corroding engine parts at one of its very few remaining plants in the city, and after the first case of household lead contamination was confirmed, in the home of LeeAnne Walters, whose children lost their hair and had persistent rashes, a year passed before Snyder’s administration announced that something had indeed gone wrong.

It’s easy to forget that Flint is not the outlier it seems to be. It is a basket case of a city, but basket-case cities are not so rare, especially in the rust belt. This catastrophe was set off by bankruptcy, but it was enabled by a normal river, an old infrastructure of pipes, and a government as creaky as its water system — each of which appears in similar configurations in many places. A USA Today investigation found that there are at least 350 schools and day-care centers in America where the Environmental Protection Agency has, since 2012, identified unsafe levels of lead in the drinking water. The problem seems particularly prominent in Maine, which has corrosive water, and in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Water contamination is going to happen in other towns too.

There was another house I went to see. My marker for finding it was a creek. I drove ten miles or so on an east–west artery south of Flint, Bristol Road, trying to make the scenery fit a five-year-old’s version of the world. Oddly, it was a tree, not the house, that confirmed I was in the right place. I had not thought of the tree even once in all the time since I’d lived with it. Now it stood coppiced to a stub, a willow between the house and the creek, but it snapped into memory as a Leica-sharp image of what it was back then, in full histrionic weep. Its limbs were my mother’s source of switches. She’d break one off and flail me for playing in the creek, which flowed to the Flint River. You should not read too much into this. I certainly don’t. It’s what people we knew did at the time.

Another memory probably has more to do with explaining why my family moved from that little house on Raskob Street to this one, at the edge of Burton. It was the mid-Fifties, and my mother caught me mouthing a penny, as children do. “Don’t put money in your mouth,” she scolded. “You don’t know whether a colored person has touched it.” Actually, my memory has her using the more incendiary label for African Americans. Most of the people I grew up with did so casually.

Her racism reflected official policy in Flint. For instance, about ten years before, in the Forties, black residents had pressured school and recreation officials into granting them access to a public pool. They were admitted only on designated days. Then the water would be drained before white swimmers came, since it was like the penny in my mother’s mind, sullied by contact. She and some of the city officials were Baptists, and so had deep-seated faith in the ability of water to remove sin and wash it away. Maybe it suited them to imagine that having black skin was a sin that remained in the water.

The auto industry drew African Americans from the South to Flint almost from the beginning of the twentieth century, but after World War II, GM began active recruitment and the trickle built to a wave, a volatile mix of hillbillies and black people. (U.S. 23, “Hillbilly Highway,” delivered Appalachians to Flint, Detroit, Ypsilanti, and Saginaw.) Between 1950 and 1960, Flint added about 13,000 white people, many of them Southerners, and the black population doubled. GM helped keep the groups apart by institutionalizing segregation, not just at swimming pools. Real-estate transactions included specific language forbidding sales to African Americans in most neighborhoods. Banks redlined. Schools gerrymandered boundaries as rigidly as Jim Crow. Once, a mix-up somehow allowed a black student into an all-white classroom, and administrators dealt by placing his desk in a closet.

Yet racism in Flint was realized geographically in curious ways, largely owing to the difference between Ford and General Motors. Henry Ford wanted nothing to do with cities, consciously founding his empire in the suburbs. Today the metonym for the auto industry is Detroit, but the reality of it was not the city itself.

GM, on the other hand, which began in Billy Durant’s carriage shop, where the river runs through downtown Flint, was from the start consciously urban. GM chose to try to keep all of its factories within the city, and, when forced to seek more land outside Flint, built close to the boundary, intending to be annexed.

Deacon Darris Berry of Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church waits for Flint residents to collect water that they will use in their homes

The segregation of that boom period immediately after World War II was imposed in city neighborhoods, but the center could not hold. White people who could afford a Chevy moved outside the city limits, and commuted in. My parents joined the exodus in their new Bel Air as soon as they were able. Certainly, there were forces in this beyond race: wide-open spaces, creeks, green grass, that sort of thing. But this system allowed white families to take advantage of the infrastructure, commerce, and employment afforded by the density of a city without paying city taxes.

The population shift pushed Flint in the direction of the Ford suburbanization model, which proved to be toxic. And, as had been the case with all things Ford during the latter half of the twentieth century, the pattern became codified in Michigan law: First was a rewrite of annexation legislation that largely prevented cities from capturing growth at their boundaries, meaning that cities lost their tax base. Second, the state decided to cap property taxes and instead share proceeds from a statewide sales tax with local governments. Over the years, the state legislature, increasingly dominated by suburban lawmakers, tweaked that formula to favor the comparatively affluent suburbs. The result has been that the proceeds of the sales tax — a regressive form of taxation on its own — are disproportionately granted to the rich.

During the Sunday-morning breakfast rush at a Bob Evans where Flint ends and the suburb of Flushing begins, I met Dan Kildee, who represents this district in Congress. Kildee is a tall, balding guy with a guileless Midwestern demeanor. We realized that both of our great-grandfathers had come to Michigan in the middle of the nineteenth century as loggers. Mine was from England by way of Ontario, his from Ireland. Kildee’s grandfather’s generation, and my father’s, came to Flint. Dan Kildee’s seat in Congress is the same one that his uncle had held for eighteen terms.

Kildee learned to straddle the city–suburb line; he represents both sides, which was clear as he worked the room, recognizing constituents and greeting them warmly, mostly with double handclasps. But Kildee, who was born in Flint, is a city guy. He founded the Genesee County Land Bank, a nonprofit that collects money to raze abandoned houses, and later started the Center for Community Progress, which develops strategies to cope with sprawl and blight in cities nationwide.

We sat down at a table and ordered our strip-mall breakfast dreck. I asked him about Flint’s changing demographics and the people who left. “They could stop cities from expanding to capture the true footprint of the community,” he said. “Hopping the border to a less costly part of the geography, it’s really grossly unfair. They are doing what they see as best for themselves, but in the aggregate it’s not good for anybody. They starve the city.”

In November, Kildee was voted into his third term. He carried 61 percent of the ballots, in a district that, like most predominantly urban areas, went blue in the presidential race. His constituents had listened to Trump’s talk of “infrastructure first” — a policy that promises investment in clean water — but they couldn’t decipher the plan in the blur of promises. “People who live in these cities don’t see the Republican Party or Donald Trump as their path forward,” Kildee said when I called him after the election. “We are turned off by his pretty obvious pandering when he talks about rebuilding and revitalizing inner cities.”

The story of the water crisis has mostly been about the city of Flint, but it shouldn’t be. Flint needs to be considered along with places like Burton. My parents’ Bristol Road house is best viewed on a map that shows Burton and Flint sitting side by side, stitched together like two squares of a quilt, and like a quilt, the image gets its meaning from the clash of colors and patterns. Today, Burton is 88 percent white, 7 percent black; Flint is 37 percent white, 57 percent black. Median household income in Burton is $42,002; in Flint, $24,679. Burton ought to be part of Flint in any concept of organic community growth, but it is a separate place, troubled by the collapse of the auto industry while still enjoying new houses, functioning schools, and drinkable water. Same deal in the clean-water towns of Davison, Grand Blanc, Flushing, Fenton, Clio, Montrose. All of these are in Genesee County, of which Flint is the seat, yet since 1960 Flint has lost half its population, of nearly 200,000, while smaller towns in Genesee County have grown. None of these places is bankrupt; Flint is bankrupt only because of how we choose to draw the lines that define place. Likewise for Detroit. This is the public-sector version of the asset-stripping that drove a binge of corporate takeovers in the private sector.

Flint is full of lead-poisoned children not because the Flint River is bad or because inner cities are a “disaster,” as Trump claims. Flint is full of lead-poisoned children because social policy is corrosive enough to deliberately engineer the bankruptcy of places where poor black people live.

My fondest childhood memories are of days spent with my father and his brothers. On weekends we would gather and build things. Brotherly banter, then tools were unpacked from pickups, mud got mixed, and a concrete wall rose — same thing they did all week in their jobs putting up houses and laying roads. One of the boys in that 1942 photo, Dale, the youngest, survives. When I visited him a couple years back, he was pushing eighty and building his new house, by which I mean swinging a hammer, not writing checks to subcontractors. I can imagine what the people who raised me would think about the city of Flint tearing down the houses they constructed, by the thousands.

Douglas Weiland, who served as the director of the Genesee County Land Bank started by Kildee, told me that occasionally houses come along that can be rehabilitated, so their organization sends in a crew, spiffs them up, and sells them as the market allows. But most don’t get offers. Perfectly good houses, tasteful old rambling Victorians, brick bungalows that would fetch half a million on either coast or even fifty miles away in Ann Arbor, won’t sell for enough to cover the cost of rehabilitation. For example, Weiland said, a Cape Cod in Mott Park — my old neighborhood — that sold for $80,000 in 2000 and then for $15,000 a few years ago, showed up on the latest foreclosure list, abandoned as worthless. He noticed it on the list because it was once his house.

To economists, the empty homes awaiting bulldozers are more than just lost houses. Houses were part of the infrastructure supporting the economic boom of the middle of the previous century, as were highways, sewers, water pipes, and water-treatment plants. For decades, engineers have been harping on the nation’s failure to care for this infrastructure, saying that our neglect places us in peril. Trump alluded to his vague ambition for an overhaul in his victory speech: “We’re going to rebuild our infrastructure, which will become, by the way, second to none. And we will put millions of our people to work as we rebuild it.” But tending to existing infrastructure is a lot cheaper than replacing it, and there is no better evidence than Flint’s water system, where $50,000 worth of treatment could have saved more than a billion. Long-term economic analysis suggests the need for even greater attention to Flint’s example: if Robert Gordon’s meticulous research is right, and the midcentury boom was a one-off, then not only is it cheaper to maintain infrastructure, that is our only choice, because nothing on the horizon — certainly not tax breaks to private investors, as Trump has proposed — promises to generate enough money for a do-over.

Gordon establishes that the setup for the economic expansion of the midcentury began in the Aughts and Teens — first in cities, and then in rural areas — with a decline in infant mortality and an increase in life expectancy. He argues that often-cited factors in the transition to the modern era, like improved medical knowledge and nutrition, were not the most transformative. Rather, he writes, babies stopped dying when sewers and contemporary public-water systems were introduced in U.S. cities. Yet today in Flint, contaminated water has flowed to at least 25,000 children, and nationally kids in 4 million households have been exposed to lead. A dozen people in Flint have died from Legionnaires’ disease, believed to be the result of poison in their taps, and the effects of contamination on children there and across the country will be harshly revealed as our pipes continue to break down.

On a crisp Saturday morning in Flint, the sky was blue, but frost still hung in the air. I drove along Martin Luther King Avenue, passing wasted, falling houses. Then I spotted a bigger, boarded-up concrete building. The front door was propped open and a guy was wheeling out stacked cases of bottled water on a hand truck to a rusty, canary-yellow Chevy at the curbside. A family loaded the water into the trunk.

This had been a school and was now a bottle warehouse, with a hint of something on the nameplate still visible: bunche community school. The building was surrounded by a weedy expanse, once a cultivated park, wooded with mature maples and oaks. A year before I arrived, a collection of neighborhood groups had bought the property, but there were no signs of rehabilitation — the place looked overgrown and neglected.

A city contractor replaces lead pipes with copper ones. The city replaces between six and eight lead service lines a day

Education, a commitment to the next generation, had been essential in Flint when I was born, and this was because of the auto industry. General Motors and the United Automobile Workers, who gained recognition in 1937 through sit-down strikes, actively bargained and collaborated to run the city and the schools and everything else — not textbook democracy, but it worked. If a resident had a problem with, say, her drinking water, she took it up with the union, and the union fixed it. This arrangement spread across the state and established broad support for schools and universities. There is no doubt in my mind that my path from that shack on Raskob Street to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor was paved this way.

Bunche Community School bears the fingerprints of one original GM principal in particular, Charles Stuart Mott, a Republican three-time mayor of Flint and very generous philanthropist. (Mott Park was named for him.) In the 1930s, Frank Manley, a local teacher, sold him on the concept of community schools. Manley’s notion, picked up from Flint’s Socialist Party, was to charge public schools with a wide mission, including adult education and courses in health and athletics, as well as enrichment classes for children. Schools were set in sprawling parks with gyms, pools, and skating rinks that were open day and night.

The Charles Stuart Mott Foundation remains Flint’s major philanthropic force. Neal Hegarty, who runs its programs, began working in the city sixteen years ago, and couldn’t help but notice that whenever locals talked about their experiences at the community schools, they would wind up in tears and say something I’d heard, too: “I didn’t know I was poor.” Hegarty told me, “This community had everything one could imagine.” All the people I spoke with about community schools said that there was an underlying message in whatever they learned: the program was a conscious effort to teach the social contract. “It led me into a lifetime of community activism,” David White, a Flint historian, said.

The community schools were segregated, however, and Andrew R. Highsmith, in his book about Flint, Demolition Means Progress, singles out the program as a Mott-funded effort to bolster racial division. Mott died in 1973, during the peak of white flight, and the foundation announced that it would quit paying for community schools in 1977.

When I met Inez Brown, Flint’s city clerk, in a well-worn conference room adjacent to her office in City Hall, she expressed no interest in lamenting the discrimination she’d experienced. She was generally polite, slight, soft-spoken, and thoughtful. As a kid she had lived down the street from Berston Field House, a community school that provided extracurricular programs in the afternoon. Black children went there to swim, and though I didn’t get this from her, Highsmith writes in his book that on days when white kids wanted to swim at Berston, the pool was among those drained and refilled. “At the time it was kind of segregated,” Brown told me. “I hate to say it that way, but it was.”

She wasn’t there to swim. She was there for the books. The schools sponsored competitions for most books read. “I can remember as a child I was interested in everything,” she said. “I wanted to be an anthropologist one time. Then I wanted to be a writer. Then I decided I wanted to be an actor.” Before she became Flint’s city clerk, Brown was an aide to Senator Don Riegle, specializing in urban policy, and then she worked in the Chicago office of the Small Business Administration during the Clinton years.

Brown could see that we were around the same age, and she said something that seemed to include us together in an important category: “You and I were both taught that every generation needs to be better than the next,” she told me. “That’s not happening anymore.”

When we spoke again after the election, she said that Trump’s form of bigotry had sounded similar to language she had heard all her life. “In every presidential election that I can recall in the past, racism has always been interjected,” she explained. “But the way it was interjected this time was in a different manner, and it did cause more anger and consternation.” Now, she told me, “We’re at a crossroads.”

Only once during my return to Flint did I allow myself to spiral into a towering rage. It didn’t happen at either of my old houses — I have left those behind — but on hallowed ground, in an open field of grass in the inner city. This place, framed by a new parking lot and a paved trail along the Flint River, was known to generations as Chevy in the Hole. It was once a sprawl of eight plants on 130 acres, where nearly 20,000 people built cars — the setting of the United Automobile Workers’ strike — and has since been become part green park, part industrial wasteland.

My rage kicked in as I approached the chain-link fence that separated the field from the river. Beyond the fence was a tilted wall that stretched along each bank all the way downtown — a mile, give or take — forming a long concrete casket. The encasement of the river was a flood-control project by the Army Corps of Engineers, in the Sixties. The auto plants on the banks had been built in a floodplain (“the hole”), and this was their truly wretched way of preventing water from spilling. Concrete channels kill rivers, directly and indirectly — it’s hard to care about a dead drainage ditch.

I suggested to people that what Flint really needed was to make the Army Corps come back and pull out the concrete. Everyone told me that this was a bad idea, even as they lined up for water bottles. Expensive. Besides, there are sites that once held factories — brownfields, now — all up and down the river, underlain by toxic waste and better left undisturbed. I still think that Flint needs to tear out this concrete, but maybe that’s just me.

My anger here was personal and misplaced. It had to do with mobility. The river lost its mobility so that we could have ours, so that GM could make Chevys to carry people to the suburbs and beyond. My father was infected with this mobile spirit, always moving, mostly because he could not keep a job. He had a pathological streak of antiauthoritarianism, and if it is genetic, I thank him for it. By the time the Sixties came around, we had left Burton, lived in Tennessee and Ohio, and come back, 200 miles north of Flint, to build a house on a corner of my grandfather’s farm. My father’s habit was to leave us there while he went away, traveling from job to job in construction, preferring his mobility over his children. In particular, he left me to fend for my six younger siblings in a house that was not equal to Michigan’s winters. He could not abide staying put, and so he went to Flint, to work in concrete, on this very project, pouring the concrete walls along the river.

From Chevy in the Hole, one can walk straight north across the bridge that Flint cops crossed with tear gas, clubs, and guns in 1937 to try to end the auto workers’ strike, and on the other side step into Einstein Bros. Bagels. At a table I found Jack Stock, director of external relations for Kettering University, and Dallas Gatlin, a longtime GM executive and former plant manager who now runs a homeless shelter.

The Einstein Bros. had been brought in by Kettering, a science and engineering school once run by GM — it was then called the General Motors Institute but known widely as the West Point of the auto industry. Now Kettering was a private nonprofit, just across the street. The site where we were eating had been a liquor store before, derelict and dangerous; Kettering works with the Land Bank to buy up such places and open mundane little amenities that elsewhere would be taken for granted. Gentrification? Maybe somewhere else, but on these streets the word gets no traction. Stock explained that the university was ultimately responsible for shielding students from crime in Flint, where the murder rate is about ten times the national average. (A shooting occurred a couple of blocks from where we sat two days later.) The university could either wall itself off or engage, Stock went on, and Kettering had chosen the latter. In March, the university began offering its employees loans of as much as $15,000 to buy houses in the neighborhood; the loans would be forgiven if the employee simply remained in the house for five years. There have been three takers.

Gatlin had joined us because his homeless shelter is part of the University Avenue Corridor Coalition, which includes Kettering, along with Hurley Medical Center, the city, GM, and some NGOs. The idea is to use the river as an asset to promote development, and a homeless shelter counts, at least in Flint. The shelter, Carriage Town Ministries, is a new facility a few blocks east, which anchors a network with a clinic, gardens, and parks for the several hundred people it serves. Residents do chores for their keep, like picking up litter along University Avenue. In winter, the homeless had started shoveling sidewalks because the city couldn’t afford to plow, and Kettering bought them snowblowers. The lessons about community responsibility once deliberately taught in Flint’s public schools now occur in its homeless shelters.

We were in the emerging core of Flint, among the “eds and meds,” as the locals say. It’s a lash-up of necessity, to fill the void created by dysfunctional governance. When state regulators actively sought to cover up the water poisoning, and the EPA tied itself in useless knots for months, the scandal came to light only because outsiders, nongovernmentals, did the spadework. These were people like Marc Edwards, an independent researcher from Virginia Tech, and Mona Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician at Hurley, one of the eds and meds from the neighborhood.

A year since the news broke, talk of Flint continues. Several state and local officials have been charged with misconduct, yet the government has not remedied the infrastructure that made public water unfit to drink. Faucet filters have been distributed, but people tend to feel safer buying water bottles. The EPA under the Obama Administration, which has seen its budget slashed and is operating with the smallest staff that it’s had since 1989, is at risk of being eliminated entirely by Trump. When asked by Fox News whether he would cut federal departments, he said, “Environmental Protection, what they do is a disgrace. Every week they come out with new regulations.”

We speak of a postindustrial society, but ours is also postgovernmental. In the halcyon days of the industrial era, the period of our greatest collective prosperity, the Eisenhower years, there were seventy-eight Americans for each employee of the federal government; today there are 150.

Before I left town, I went to see Heidi Phaneuf, a city planner by training, who was working to take the city apart. The Genesee County Land Bank had hired her to help manage their house-demolition project. She got her degree at the University of Michigan campus a couple of blocks away from her office, which was downtown, by the river. When Phaneuf greeted me, her preternatural pleasantness and youthful laugh made her seem green. But she isn’t, not after having been through all she has.

Phaneuf lives in the Grand Traverse neighborhood, a thin strip of resurrection and stately old wood-frame houses just south of the river. Hers is the same house that her grandparents lived in. When the roof and foundation caved, she and her husband tried to borrow enough money — some $20,000 — to renovate. The banks refused, but cheerfully offered to loan them $100,000 to move to the suburbs. They stuck around, scratched together the money a bit at a time, and did the work themselves. “My car is worth more than my house,” she said. The house is valued at $12,600.

Mostly, Phaneuf’s work is to be an urban undertaker, and like an undertaker her greatest service is easing Flint residents through denial, and perhaps several other stages of grief, about the death of their neighborhoods. She showed me maps, as planners do. Hers depicted Flint over recent years, with each progressive year showing increasing concentrations of black dots that signified demolished houses. Many were north of the river, above the heart of Flint, and a few were south and along the city’s commercial arteries. There were big blank spaces where factories once were. I asked her about where this was headed, insisting that she was a planner so what was the plan, and then I realized that this was irrelevant. What she understood and I had not was that she was not redrawing these maps herself.

Once, maps detailing Flint’s future were drawn by the heavy hand of GM to create a habitat for its workers. GM is gone, and with it nearly 100,000 people. Still, as many remain, compelled by their commitment to the social contract. And there are newcomers, artsy urban pioneers drawn by $15,000 houses. Circumstances have presented Phaneuf and others with an opportunity to fill in the blanks with a city designed to meet the needs of those who live there now, the needs of people, not of a governing corporation. (Since we met, she has taken a new job, as a planner at the Michigan Department of Transportation.) Flint is feeling its way toward a postindustrial, postgovernmental future, and we all have a stake in the outcome.

I came away from Flint with a preoccupying question: whether the place where I grew up could still serve children the way it had served me, by offering a pathway to a valuable life. No one I talked to on my trip saw how it could. Like many in my generation, I desperately want the path remade, and I have cast about for the dimly recalled elements of prosperity and social commitment that allowed it. None of my best-laid plans, or anyone else’s, will pull us from the ditch we are in. We can only watch as this city redraws itself along its one meandering bold line: the river.