(1)

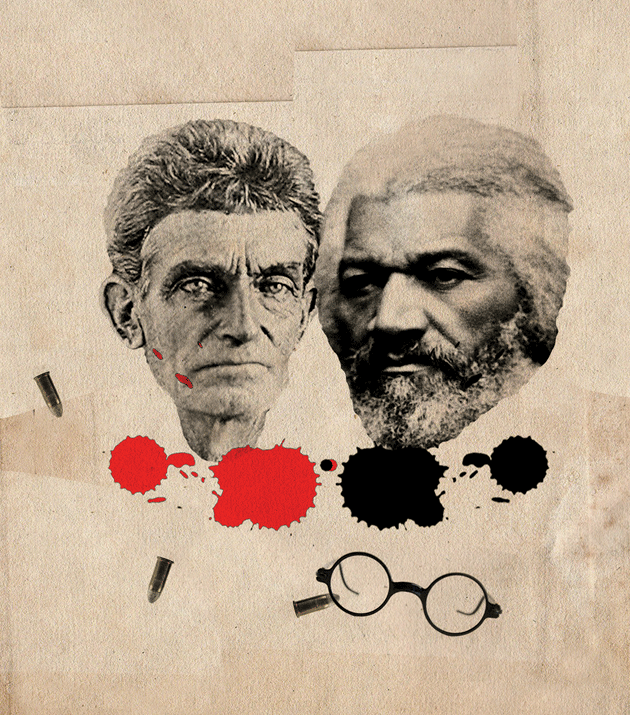

To need his glasses and be struck by an awareness that they are not at hand, an ordinary enough circumstance for Frederick Douglass, except sometimes it’s accompanied by a flash of extraordinary dread. If not quite panic, certainly an unease disproportionate to a simple recurring situation. Dread that may be immediately extinguished if he locates his horn-rimmed, owlish-eyed spectacles exactly where he anticipated they should be.

He sees them and almost sighs. Nearly feels their slightly uncomfortable weight palpable on his nose. Finding the glasses enough to reassure him that he remains here among the living in this material world where he depends on glasses to read, glasses to help him negotiate stubbornly solid objects he cannot glide through. Enough to remember that he’s able to recall or backtrack, anyway, and understand how the present moment connects to moments preceding it, a trail of hows and whys causing him to wind up where he is now, at this particular moment, stretching out a hand to pick up eyeglasses because he is the same person who placed them on the desk, beside a stack of three books at the desk’s upper-left-hand corner so he wouldn’t forget, and there, here they would be when he needed glasses.

Sometimes dread does not vanish when he locates his glasses. They turn up where he thinks they should, his fingers curl, prepare to reach out for them. But glasses are not enough. Not convincing enough. They do not belong to him. Not glasses. Not hand. He vaguely recognizes both. Glasses too heavy to lift. Or hand too heavy. He’s observing from an incalculable distance, and sometimes that detachment is a gift, sometimes it dooms him. He cannot animate or orchestrate what he desires to come next. John Brown spreads his ancient, musty wool cloak — cloak the brown color of his name — over glasses, books, desk, study, house, wife, him, and when John Brown snatches the cloak away, nothing’s there. Douglass has fled to the mountains, the woods to join him.

(2)

Ah, Frederick, my friend. Look at you, Fred Douglass. I knew after a single glance you could be the one. Your manly form and bearing left no room for doubt. And today these dozen hard years later you still stand tall, straight, gleaming. I see God’s promise of freedom in you. Yours. Mine. Our nation’s. A man who could lead his people, all people, out of slavery’s bondage. Your beard dark that day we first spoke and now tinged with spools of gray, but you gleam still, my friend. Despite the iron cloud of suffering and oppression slavery casts over this land.

Douglass remembers no beard. Not wearing one himself, nor a beard on Brown’s gaunt face. Certainly not the patriarch’s thicket of white flowing — no, a torrent — today halfway down John Brown’s chest. He misremembers me.

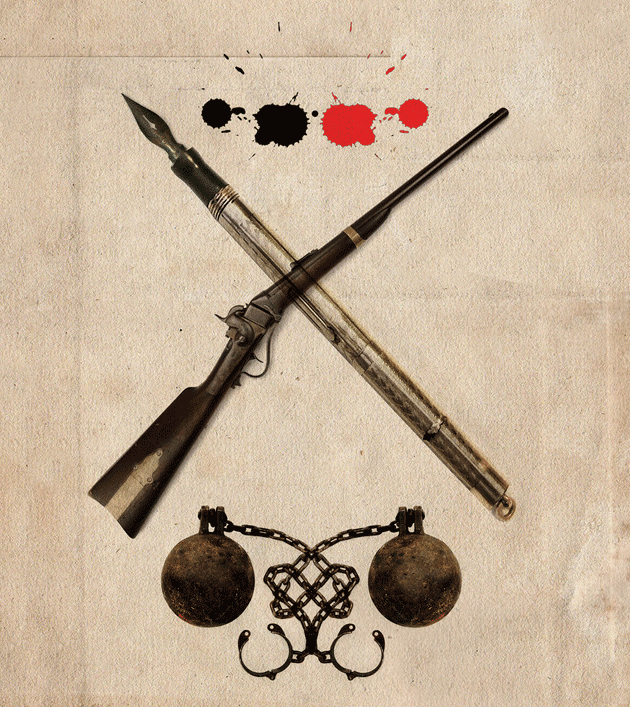

But if God ignites a man to believe himself a prophet, if visions burst upon him and seize him, as an ordinary man is seized by a roiling gut and must rush behind a bush to squat and relieve himself, if such urgency is the case, I suppose, Douglass instructs himself, a prophet can be forgiven for mistaking petty details. Prophecies forgiven for confusing time and place, for compounding truth and error, wisdom and foolishness, for mixing wishful thinking with logic. John Brown forgiven for believing that ignorant, isolated slaves, cowed into submission by a master’s whip, will grasp the purpose of a raid on Harpers Ferry and flock instantly to his banner. Enraptured by his vision, Brown foresees colored slaves armed with sticks and stones prevailing against cannons, Sharps carbines, the disciplined troops of a nation dedicated absolutely to upholding the principle that color makes some men less equal than others. I embrace the fiery justness of John Brown’s prophecies, his unflinching willingness to sacrifice himself and his sons, yet I cannot forgive my friend for untempered speech, demagoguery, the impetuosity and rage that grip him. That transform dream to madness.

(3)

Douglass watches himself step out from behind the curtain and stride to the bunting-draped podium. They will welcome him. He is famous. Broad chest bemedaled, gold baton, field marshal’s crimson sash decorating his resplendent uniform, veteran of a terrible war, though he never fired a shot in anger. Fine figure of a man still. After seven decades on earth. After a protracted, blood-drenched conflict settling nothing. Certainly not settling his fate. Nor his color’s fate. Nor his nation’s.

A drumroll of applause greets him, deepening as he moves step by step across the stage, a thunder of hands accompanying him. In the front rows his new white wife’s white women friends. When a journalist asked Douglass to speak about his marriage, seeking details to spice the story he intended to write about newlyweds whose union scandalously ignored great disparities of age and race, Douglass replied, “My first wife the color of my mother, second the color of my father.”

Tonight in this hall where he’d spoken once before, where once he’d been property, a fugitive hosted by abolitionists, a piece of animated chattel curiously endowed with speech, tonight in this hall he would address “The Woman Question.” Proclaim every woman’s God-granted entitlement, like his, to all the Rights of Man.

A born orator. Born with that gift and many glorious others, his mother assured him in stories told at night, whispering while she lay next to him in the darkness, their only time together, half hours she stole from her master, slipping away to walk an hour each way, plantation to plantation, to earn their half hour.

Second rumble of applause when he concludes his remarks. Head bowed, he waves away the noise and stirs it, conducts it, loves it even as his gesturing arm seems dismissive, seems modest, a humble man, a veteran tempering, allaying the crowd’s enthusiasm just as he strokes and soothes and quiets and fine-tunes his new young wife’s pale hair and pale skin, her passion that makes him tender, wistful, as often as aroused. These happy newlyweds. Her ferocious coven of female friends among the loudest of clappers.

The evening will be a success, and he will return home to drop dead. Douglass dead as suddenly as Lincoln felled by an assassin’s bullet. Except the president lingered. Douglass won’t. Dead. He sees this as surely as he sees his old face in the vanity mirror in their freshly papered bedroom. As surely as old man Brown saw blood. Only pools, rivers, an ocean of blood, John Brown swore, would cleanse the sin of man-stealing. No. Not cleanse. Not expunge or redeem or expiate. No. Blood must be shed. No promises. No better, cleaner South or North. Only a simple certainty that blood must be shed. Douglass read that dire text in Brown’s distracted gaze, his stare. Same fire in himself as a boy who struck back, no fear of consequences, at bullying slave driver Covey. Same fire fanned by waves of hands striking hands that primes him, guides, draws him as he crosses to a podium. Fire in the young woman he’s taken after forty years with his colored first wife, this second wife who will discover him lying comfortably on the floor as he would have been lying comfortably across their canopied bed awaiting her had his heart not stopped and dropped him like an ox, Douglass lying there on the Turkish carpet he sees so clearly now and never will again. Won’t see it when he falls, when the abyss blackens suddenly and his head slams down into the rug’s elaborately woven prayers.

(4)

Through a smallish window in a small motel I watched snow falling, a heavy snow, probably more than enough coming down to transform in a couple of hours the unprepossessing landscape framed within the motel window. Big white flakes dropping effortlessly from the sky as I’d hoped all morning words would materialize on the page while I’d sat here in this unprepossessing room attempting to imagine a boy alone on a wilderness trail who drives his father’s cattle along the shore of Lake Erie, perhaps a hundred-mile-plus trip there and back, to supply a military encampment during the War of 1812, the boy on a horse or a mule, I assume, although it’s possible he may have been on foot, armed with a long stick or a cudgel to protect himself and prod the stream of cattle along whichever edge of Lake Erie he advances — north, south, east, west — from Hudson, a small, new town in Ohio’s Western Reserve, where the boy’s family lives, to a base on the Detroit front occupied by a General Hull and his troops.

I had never been a white teenager with a strict, pious Calvinist father named Owen Brown whom I had accompanied often on cattle drives, never punched cows alone, never a slave like the boy his age John Brown immediately would befriend and never forget, the colored boy encountered in an isolated cabin located somewhere along his route. Very likely John Brown himself couldn’t say exactly where, disoriented by an unexpected snowstorm that erased the usual familiar terrain and forced him for caution’s sake to seek shelter for his animals and himself before nightfall, before he found himself lost completely, not sure how far he may have drifted from the trail, not even clear in which direction the trail might lie after hours of thick, swirling snow, certain of nothing but snow, wind, chilling cold, and the necessity to keep track of the cattle, perhaps round them up, count them, maybe drive them into a tight circle for warmth, cows huddled, hunkered down in a ring, and maybe him or him and his horse or mule bedded down close enough to share the heat of three, five, seven large beasts in a heap, a dark snowdrift in the middle of nowhere. Or perhaps drawn by the sight of a cabin ahead, you keep the animals moving as best you can and ride toward it, then dismount, or you’ve been plodding on foot and you reach a door and knock, share the unhappy story of your plight, the errand your father entrusted to you, his livestock, his livelihood, delivering beef for General Hull’s soldiers to eat so the Brown family can eat, so there’s food on the table back in Hudson. Not army beef — cornmeal mush his mother measures, spoons out to John Brown and his siblings Ruth, Salmon, Oliver, and Levi Blakeslee, an orphan who, thanks to Owen Brown’s charitable heart, was adopted and traveled as part of the Brown family to Hudson from New York State. Taut, hungry, lean faces at home, and now John Brown’s duty to feed them.

Night deepening. Storm emboldening him, a shy twelve-, thirteen-year-old boy, to seek assistance, refuge, only or at least till daylight and he can relocate trail or landmarks and be on his way.

John Brown’s storm does not subside but intensifies, lasting through the next afternoon perhaps, so he stays a night and half the following day in a cabin with a settler and his family, stranded here in a stranger’s cabin for far too long, too far away from accomplishing his task, Owen Brown’s cows outside maybe wandering off, lost in blinding snow. How many of them? Count them, band them together, search for strays, coax up the slovenly ones who otherwise would be content to die where they kneel, sunken into the snow.

These people pioneers of sorts, like his, hovering at the edge of raw wilderness, a question arising daily, as predictable as the sun: will they survive for another twenty-four hours on this not-quite-civilized frontier, prayers each time they awaken, each time they break bread. The bread coarse, dark, hard, a little milk on occasion or water to soften it, a rare dab of honey to sweeten, or it’s cornmeal porridge or cornmeal fried in grease to make a square of hot mush on his dish like John Brown receives that night in a cabin familiar to him from home, the wooden plates and heavy mush no strangers, nor the wife who smiles twice — John Brown notices, counts — during the hours of his stay.

She reminds him of his mother — busy without a pause, quiet as a shadow, a kindly shadow, she lets you know without saying a word, nor could you say how you know that deep kindness and deep fear hide inside her busyness, her mouth like his mother’s a tight line, lips nearly invisible even when she unseals them to address briskly, not often above a tight whisper, her three tiny girls or the man who is her husband, who’s quite impressed by any youngish boy a father would trust to drive cattle along miles and miles of wilderness trail, a man who offers encouragement to John Brown to linger longer, though the boy and perhaps the host know he must refuse and he will, politely, this well-spoken boy. The boy understands his mission. He’s determined, as long as he can draw breath into his body, to reach his destination and discharge his responsibilities. Then walk, ride, or crawl back to Hudson, money collected in hand, hurry, hurry, not a moment to spare, since so many crucial hours consumed, lost, wasted already.

Not a problem for me to imagine his anxious state of mind, his despondency and disappointment with himself, his sense he could, should have been better prepared for any emergency that might sap precious time. His sister Ruth would not understand why her bowl is empty. Her big eyes, severe even when a very young child, hold back tears she knows better than to shed, not because she fears being disciplined for weeping at the dinner table — her parents love her, teach her, pray over her and with her every day. She doesn’t cry because she doesn’t wish to disappoint or hurt them, tears would vex her mother, worry her father, tears might cause them to think she is blaming them for no food or, worse, blaming the Good Lord when she knows He is always watching over her, His grace abounding, more precious than thousands of earthly platters heaped with food.

John Brown imagines Ruth inside him and peeks out at himself with her deep, famished eyes, the way the slave boy looks at him, speaking with eyes, gestures, a silent conversation, a wordless friendship struck up with the first glances they exchange, fellow outsiders, alien presences in the cabin, raw boys of similar size, age.

John Brown winces but holds his tongue, his tears, when the dark boy cowers under a sudden flurry of blows, many thuds, cracks across his back, shoulders, arms, not ducking or fleeing, hands not thrust up to protect himself from a series of blows delivered by a stout stick that must have been leaning against the head of the rough log table, stationed there at the man’s hand, John Brown immediately perceives, for exactly this purpose. Rapid, loud strikes, blows that are — is it fair to suggest? — as painful in John Brown’s mind as they are on the slave boy’s body, fair to say the sting of this not-uncommon beating cools soon and is forgotten by a black boy’s tough flesh, but a white boy’s shock endures. What a surprise to John Brown the evil in the heart of this grown-up man who has been nothing but kind to him, offering succor from a storm to one of his kind, a stranger, a mere feckless boy who let down his father, his family. A father like his father but unlike too, as John Brown feels himself alike and unlike the black slave boy his age who serves them, who eats and sleeps under the same roof with this family, with him that night, but in a corner. Eats over there, sleeping there under rags, rags his bedding, clothes, roof, walls, floor all nothing but rags, a dark mound of rags the wind has blown into the house perhaps when the door opened to let John Brown enter or leave or when the man who’s father of the house passes in and out to piss or the slave boy’s endless chores drive him into the storm to do whatever he’s ordered to do until he’s swept by a final gust of wind one last time back into the cabin, a piece of night, ash, cinder trying to stay warm in a corner where it lands.

(5)

Spring rains swelled the rivers the year my sons John and Jason set off to join their brothers in Kansas and be counted among antislavery settlers when the territory voted to decide its future as a free or slave state. They left Ohio with their families, traveling by boat on the Ohio, then Mississippi Rivers to St. Louis, Missouri, where they bought passage on a steamer, the New Lucy, to reach the camp at Osawatomie that the family had taken to calling Brown’s Station.

A long, cold, wet journey to Kansas, Douglass, and on the final leg God saw fit to take back the soul of my grandson, four-year-old Austin, Jason’s elder son, stricken during an outbreak of cholera on board the steamer. When the boat docked at Waverly, Missouri, the grieving families of Jason and John, despite a drenching thunderstorm, disembarked to bury young Austin. The boat’s captain, a proslavery man surrounded by his Southern cronies, the same ruffians who had brandished pistols, bowie knives, swearing oaths, shouting obscenities, swaggering, and announcing their bloody intent to make Kansas a slave state, the same brigands who had terrorized their fellow passengers night and day, singling out my sons whose accent and manner betrayed them as Northerners, all those devils must have laughed with the captain at the cruel joke he bragged he was playing on the bereaved families, dumping their meager baggage to soak and rot on the dock, steaming away from Waverly before the distraught mourners returned from their errand, abandoning them during a downpour in a slave state though they had paid fares to Kansas.

No simple business to slaughter men with broadswords. To hack and slice human flesh with less ceremony than we butcher sheep and pigs. Dark that late night, early morning in Kansas when we descended upon homesteads of the worst proslavery vigilantes and fell to killing along Pottawatomie Creek. I was in command. Ordered the guilty to come out from their homes. Ordered executions in the woods. I knew the men I condemned had assaulted and murdered peaceful settlers, and among their victims were members of my family. Still, I stood aside at first, appalled by the fury, blood, screams, the mayhem perpetrated by weapons wielded by my sons Owen and Salmon and our companions. Though I entertained not the slightest of doubts, Frederick — the awful acts committed that day were justified, even if they moved the clock only one minute closer to the day our nation must free itself from the sin of slavery — yet I stayed my hand until the quiet of dawn had returned. Then, in silence broken only by his pitiful moans, I delivered a pistol shot to the brain of a dying James Doyle.

(6)

Here is a letter (some historians call it fiction) written by Mahala Doyle in the winter of 1859 and delivered to John Brown awaiting execution in his prison cell in Virginia:

I do feel gratified, to hear that you were stopped in your fiendish career at Harpers Ferry, with the loss of your two sons, you can now appreciate my distress in Kansas, when you . . . entered my house at midnight and arrested my Husband and two boys, and took them out of the yard and shot them in cold blood, shot them dead in my hearing, you can’t say you done it to free slaves, we had none and never expected to own one, but has only made me a poor disconsolate widow with helpless children. . . . Oh how it pained my heart to hear the dying groans of my Husband & children.

(7)

On the road between Cleveland and Kansas, gazing up at the stars, John Brown’s son Frederick said, “If God, then this. If no God, then this.”

John Brown remembers the wonder in Frederick’s voice, how softly, reverently his son spoke, so many stars overhead in the black sky, remembers the wagon wheels’ jolt, yield, bounce had spun a seemingly unending length of rough fabric from the road’s coarse thread, then a seamless, silky ride for John Brown lasting until Frederick’s words returned him to an invisible chaos of slippery mud, rocks, craters that snatch them, tumble them, rattle their bones. Any moment a sudden, unavoidable accident might pitch both men overboard or smash the wagon to splinters as it traverses this broken section of road between Cleveland and Kansas, and there is no other road except the one spun for a few minutes during John Brown’s forgiving sleep, his forgetful sleep.

How many minutes, hours, how much unbroken silence of sleep before he awakened abruptly to hear his son Frederick’s voice asking how many miles covered, how many more miles to go to Kansas, Father. His poor, half-mad, feeble-brained son, the one of all his children, people agree, who resembles him most in face and figure, Fred loyal and uncomplaining as a shoe. Tall, sturdy Frederick, who will die in a few weeks in Kansas. Dead once before as an infant, then reborn, rebaptized Frederick in remembrance of his lost little brother. Frederick’s second chance to live cut short by ruffians in a border war, my second perished Frederick. Then a third chance, a dark son or dark father or mysteriously both, bearing the same name my sons bore, Frederick, and John Brown trembles after his sleeping eyes pop open when he hears his son’s declaration, Frederick’s soft blasphemy revealing his wonder at a thought he had brewed all by himself while he drove the wagon transporting father and son to the killing fields of Missouri and Kansas, driving through this great holy world, this conundrum, John Brown thinks, far too perplexing, too fearful for a father to grasp or explicate.

In his cell in Virginia John Brown will remember riding in a wagon at night with his dead son Frederick on the way to rejoin family in the camp in Kansas. His arm stiffens, his fist grips the hilt of an imaginary broadsword, and he mimics blows he witnessed in predawn darkness, blows his sons Salmon and Owen inflicted on outlaws they attacked on Pottawatomie Creek. This stroke for a dead grandson, Austin. This one for dead baby Frederick. This for Frederick who shared his lost brother’s name and died too soon, twenty-six years old, in those Kansas Territory wars. And more blows struck for other, darker Fredericks, all of them his children, God’s children, Brown almost shouts aloud as he presses again a revolver’s actual barrel against the skull of whimpering, murdering night rider Doyle. An act of mercy or vengeance? he will ask God in his cell, to end the suffering of a nearly dead evil wretch when he pulls the trigger.

(8)

1856

Mrs. Thomas Russell wrote:

Our house was chosen as a refuge because no one would have dreamed of looking for Brown therein . . .

John Brown stayed a week with us, keeping his room almost always, except at meal time, and never coming down unless one of us went up to fetch him. He proved a most amiable guest, and when he left, I missed him greatly . . .

First time that I went up to call John Brown, I thought he would never open his door. Nothing ensued but an interminable sound of the dragging of furniture.

“I have been finding the best way to barricade,” he remarked, when he appeared at last. “I shall never be taken alive, you know. And I should hate to spoil your carpet.”

“You may burn down the house, if you want to,” I exclaimed.

“No, my dear, I shall not do that.”

Mrs. Russell goes on to record that John Brown

had the keenest possible sense of humor, and never missed the point of a joke or of a situation. Negroes’ long words, exaggerations, and grandiloquence afforded him endless amusement, as did pretentiousness of any sort . . .

He was acute in observing the quality of spoken English, and would often show himself highly diverted by the blunders of uneducated tongues. He himself spoke somewhat rustically, but his phrases were well formed, his words well chosen, and his constructions always forcible and direct. When he laughed he made not the slightest sound, not even a whisper or an intake of breath; but he shook all over and laughed violently. It was the most curious thing imaginable to see him, in utter silence, rock and quake with mirth. . . .

1858

John Brown thinks of it as molting. His feathers shed. A change of color. Him shriven. Cleansed. Pale feathers giving way to darker. Darker giving way to pale. Not seasonal, not a yearly exchange of plumage as God sees fit to arrange for birds or for trees whose leaves alter their hue before they drop each fall. His molting occurs in an instant. He stands naked. A tree suddenly stripped of leaves. Empty branches full again in the blink of an eye.

I see such alterations in myself, Douglass, in my dreams and often in God’s plain daylight, and wonder if others notice my skin falling away, turning a different color, but I do not ask, not even my wife or children, for fear I will be thought mad. One more instance of insanity my enemies could add to discredit me. Old Brown changes colors like a bird or a leaf. Pure insanity to believe a man sheds one color and becomes another. Or worse — those in league against me would aver — much worse if Brown doesn’t believe the falsehood yet would propagate a dangerous lie to lead weak minds astray. Proof positive that Brown is an emissary from Hell busy performing the Devil’s work.

Free slaves, mad Brown shouts. Free the coloreds, as if color simply a removable outer shell, as if color doesn’t permanently bind men into different kinds of men. As if feathers, leaves, fur, skin, fleece, all one substance, and all colors a single color. Yet I believe they are the same in God’s eye.

I thank you again for the kindness and generosity you and your wife have extended toward me. I arrived here weary, despondent, exhausted by the Kansas wars, and you offered shelter. A respite from enemies who pursue me as if there’s a price on my head here in the North as well as in the South. Your welcoming hand and spirit have revived me. I have been able to think. Write my Constitution. When not occupied by my pen, I have benefited from your willing ear, your thoughtful responses to my poor attempt to draft a document that protects every American instead of a privileged few. I am eternally indebted to you for the sanctuary you provided, for your unceasing hospitality these last three weeks, and to demonstrate my gratitude, I’m ashamed to admit, I ask for even more from you. Not for myself this time, but for the grand cause we both are destined to serve. You must join us in Virginia, Frederick Douglass.

Why are you certain that my enslaved brethren will “hive” to you, as you put it? Why certain that a general insurrection will follow the Harpers raid and topple the South’s slaveholding empire, free my people from bondage? I agree with much of your reasoning and share your sense of urgency, but do not share your certainty. Envy it, yes, but do not share it. You cite Toussaint’s successful revolt in Haiti and Maroons free in the hills of Jamaica. Yet Virginia is not Jamaica, not Haiti. I believe there must be better ways than bloody rebellion to end the abomination of slavery. Why are you so certain God looks with favor on your plan? What if, despite your fervor and good intentions, you are wrong?

Wrong, you say. Wrong. In this nation where a man’s color is reason enough to put him in chains. Where cutthroats in Kansas murder settlers whose only offense is hatred of slavery. Where a senator is caned in the halls of Congress for condemning man-stealers. Why, in a nation where every citizen compelled by law to aid and abet slave-masters who seek to recover escaped “property,” is it difficult to separate right from wrong?

I tremble as I utter this chilling thought, Frederick Douglass, but what if no God exists except in the minds of believers? Would it not behoove us more, not less, to bear witness to what is right? To testify? To manifest, in our acts, the truth of our God’s commandments?

I make no claim to be God’s chosen warrior. I have studied an assault on the Virginia arsenal for a very long while. Devised a strategy I believe will exploit a powerful enemy’s weaknesses. Recruited and trained good men to fight alongside me and my sons. Weighed both moral and practical consequences. Asked myself a thousand times what right do I have to commence such an undertaking. Still, I would be a fool to think I’m closer to knowing God’s plan. We serve Him in the light or darkness of our understanding.

Stand with us. You would be a beacon, Frederick. Let Southerners and Northerners, freemen and the enslaved, see the righteous power, the fierce, unquenchable spirit I recognized in you the first time we met. Let the world know that you are aroused, aggrieved. That you will not rest until your brethren are free. Teach your fellow countrymen there can be no peace, no forgiveness as long as slavery abides. Accompany us to Virginia. Strike a blow with us.

1859

I must die one day, John Brown, sure enough. But I feel no need to hurry it. I don’t reckon that ending my life in Virginia will make me a better man than one who chooses to survive and dedicates himself to serving God and his people. I shall continue my work here in the North. Offer my life, not my death, to my people.

I respect your well-known courage and principles. Nevertheless, I must speak bluntly, and say that I believe you quibble. You speak as if a man’s time on earth is merely a matter of hours, days, years.

In this business we cannot afford to bargain. To quibble about more time, less time, a better time. We are not accountants, Fred. Duty requires more than crying out against slavery, more than attempting to maintain a decent life while the indecencies of slavery are rife about us. To rid the nation of a curse, blows must be struck. Blood shed. I am prepared to shed blood. Mine. My sons’.

And my blood. And the blood of young Green here, fresh from chains, who, after listening to us debate not quibble, chooses to accompany you to Virginia.

Some days, I assure you, my feet, my mind rage. Yet a voice intercedes: do not give up hope for this intolerable world. Change must come. Like you, I believe the Good Lord in Heaven has grown impatient with this Sodom. Soon He may perform a cleansing with His glorious, stiff-bristled broom. I will rejoice if He calls me to that work.

I have made up my mind as you have made up yours, John Brown. And this man, Green, his mind. Godspeed to you both.

(9)

My name is John Brown and I want my son to hear the story of my name so I will talk the story to this good white lady promises to write down every word and send them in a letter to my son in Detroit on Pierce Road last I heard of him and his wife and three children, a boy and two girls, don’t know much else about them, must be old by now, maybe those three children got kids and grandkids of they own and I never seen none them with my own two eyes, these old eyes bad now don’t see much of anything no more, wouldn’t hardly see them grands nor great-grands today they standing here right beside this bed so guess I never will see them in this life and that fact makes me very sorry, son, and old-man sorry the worse kind of sorry, I believe, and let me tell you, my son, don’t you dare put off to tomorrow because tomorrow not promised, tomorrow too late, too late, but don’t need to tell you all that, do I, son, you ain’t no spring chicken, you got to be old your ownself, ’cause I comes into the world in eighteen and fifty-eight just before the war old John Brown started and seems like it wasn’t hardly no time before here you come behind me, me still a boy myself, but I want to tell you the story of my name not my age and how you supposed to know that story less I tell it and this nice lady write the words and maybe you read them one day to my grands and great-grands, son, then they know why John Brown my name and why John Brown a damn fine name, but listen, son, don’t you ever put off to tomorrow trying to be a good man, a honest man, hardworking, loving man, don’t put it off ’cause that gets a man in trouble, deep-down trouble, ’cause time is trouble, time full of trouble, and time on your hands when your hands ain’t doing right fills up your time with trouble, then it’s too late, your time to do right gone, you in the middle of doing evil or trying not to or trying to undo evil you done and time gone, too late, like me in a cage a dozen and some years locked up behind bars for killing a fella didn’t even know his name till I hears it in the courtroom and lucky he black everybody say or you wouldn’a made it to no damn courtroom, no jail, crackers string your black ass up, the other prisoners say, you lucky nigger, they say, and cackle, grin, and shake they heads and moan and some nights make you want to cry like a baby all them long, long years when if I ain’t slaving in the fields under a hellfire sun I’m sitting in a cell staring at a man’s blood on a juke-joint floor, never get time back once I yanks a bowie knife out my belt and he waving his knife and mine quicker finds his heart, the very same bowie knife my father Jim Daniels give to me and John Brown give to him, said, Use this hard, cold steel, Mr. Jim Daniels, on any man try to rob your freedom, same knife old John Brown stole from the crackers like he stole my daddy, mama, my sister and brother, and a passel of other Negroes from crackers down in Kansas and Missouri, it’s too late, too late, knife in my hand, I watched a man bleed to death inside those stone walls every day year after year, hard time, son, you wait too long to do right it’s too late and you can’t do nothing, can’t change time, and that’s that, like the fact I never seen my grands, never seen you but once, one time up there on the Canada side in all that cold and snow and wind, your mama carried you all them miles, had you wrapped up like you some little Eskimo or little papoose. It was only once only that one time I ever seen you there you was with your mother, she come cross with you on the ferry, and me and her talked or mize well tell it like it was, she talked and I kinda halfway listened but I didn’t want to hear nothing I wasn’t ready to hear, nodded my head, smiled, chucked you under your chubby double chins, patted her shoulder, smooched her beautiful brown Indin-color colored cheek a couple times, always liked your mama, but the problem was I didn’t know then what I know now, son, or excuse me, yes I did, I knowed it just as clear as day, course I did, just didn’t want to hear it ’cause I had other plans, knucklehead, young-blood plans, what I’ma do with a wife and baby, it was rough up there, barely feed myself, keep a roof over my head, if you could call a tent a roof, so how am I supposed to look out for you all, anyway, it was only that once I seen you, then same day she’s back on the ferry she’s gone, you gone, nothing, no word for lots and lots of years ’cept a little tad or tidbit the way news come and go in prison or hear this or that happened from people passing through up there in Canada, me asking or somebody telling tales they don’t even know my name who I am or know you or know who your mama and who you is to me or who my peoples is, but I’d overhear this or that in somebody’s story and so in a manner of speaking I kept up, knew you still alive, then your mama dead and you married living on Pierce Road in Detroit, three grandkids I ain’t never laid eyes on, never will now . . .

Excuse me, Miss, you got that all down so far or maybe I should slow up or maybe just go ahead and shut up now, stop now ’cause how you think this letter find him anyway even if I say it right and you catch every word I say on paper it still don’t sound right to me hearing myself talk this story, it just makes me sad, and it’s a damned shame, a mess anyway, too late to tell my son my daddy, his granddaddy, Jim Daniels, give me John Brown’s name because John Brown carried us out from slavery fall of 1858, my brother and sister, mama, and Jim Daniels, my father cross seven states, 1,100 miles, eighty-two days in wagons, railroad trains, on foot, boats, along with six other Negroes John Brown stole from slavery in Kansas and Missouri and Daddy say one them other six, a woman slave, ask John Brown, “How many miles, how many days, Captain Brown, we got to go before freedom?” and John Brown answer her and the lady slave say back, “That’s a mighty far piece you say, Captain, Sir. Ole Massa pitch him a terrible conniption fit we ain’t back to fix his dinner,” and then me born on one them last couple days before they cross the river to freedom, so my daddy Jim Daniels named me John Brown, he told me, and if I’da been more than half a man when you and your mama come up there I woulda took care of you all and passed my name on to you and you be another John Brown whatever else my sweet Ella called you you’d be John Brown, too, and if you knew the story of the name, son, maybe you would have passed the name on, too, John Brown, and maybe not, Miss, what do you think, Miss, is it too late, too much time gone by, Miss, what do you think?