On the morning of June 26, 2015, barely two hours after the Supreme Court handed down its decision to uphold same-sex marriage, Barack Obama delivered the eulogy for nine murder victims at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. With impeccable timing, he moved from word to song, invoking grace and then singing of its sweetness and redemptive power. To some practiced ears, the president resembled an earnest college boy trying to mimic a field recording. But whether his performance was improvised or not, the product of spirit feel or political instinct, it was a rhetorical coup, almost without precedent. Obama knew that the black church’s most famous leaders had expressed rigid opposition to gay rights. But with “Amazing Grace” — whose reference to “dangers, toils, and snares” makes it a kind of secret gay anthem — he preempted their complaints. Pleading the blood at Mother Emanuel, he robbed them of their song.

Many black politicians have supported gay rights, of course. But the fact is that the leaders of the mega-churches, the men who draw thousands every Sunday, have been stark reactionaries. Pastors and worshippers alike consider “gay rights” an oxymoron, tastelessly equating fallen women and perverts with people of color.

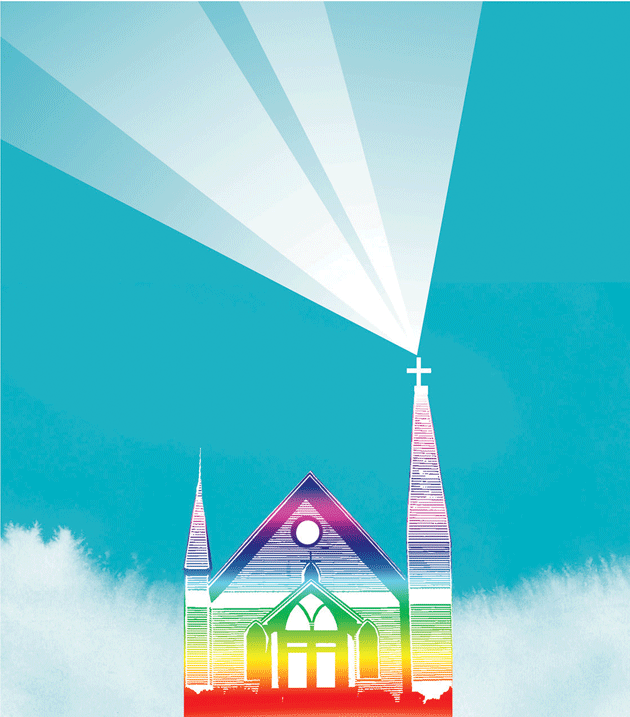

To insiders, meanwhile, the church’s war on gay people is a case of massive bad faith. For the reality is that they all know better. Every megachurch pastor, black or white, is aware that religion is one of the gay arts, along with ballet, gymnastics, and lyric poetry. Just think. Without gay men, no Sistine Chapel, no Last Supper, no “Ave Maria,” probably no “Hallelujah Chorus.” And without gay people, gospel music would shrivel and die. It would be (as I have written elsewhere) like Germany without the Jews.

To expand on that last point: it’s generally accepted that the masters of modern German prose are two Jewish writers, Franz Kafka and Joseph Roth, and Thomas Mann, with his Jewish wife and six half-Jewish children. The editors and publishers of all three men were Jewish, as were their most informed readers. The parallel to the black church, whose despised subculture is also the jewel in its crown, is impressively exact. Wherever the church has flourished, in New York or Chicago, Philadelphia or Detroit, Oakland or Atlanta, gay men have been the leading musicians, soloists, and choir singers. (As one famous female evangelist pointed out, “You all can’t have church without some sissy pumping out the organ.”) They have also swelled the ranks as Sunday-school teachers, missionaries, treasurers, elocutionists, and usher-board captains.

Even when they haven’t been the preachers — and they sometimes are — they have constituted the pastors’ inner circle and praetorian guard. Music dominates the traditional black church; the minister is as much cantor as village explainer. In particular, a good “Mississippi whoop,” or melodic growl, has been the making of many a preacher. And when the minister growled, the gay organist would accent his every moan, while the gay choir members made their joyous noise, and the gay saints (i.e., members of the flock) jumped to their feet, clapping and dancing in the spirit. The whole experience was orchestrated and annotated by gays and lesbians. This is one reason why many straight men have shunned the church — why, for example, the Reverend Jesse Jackson was ashamed to tell his mother that he had joined a choir.

Church has long presided over African-American culture as the one place where parishioners could “kick off their shoes and be real.” For intellectuals like Richard Wright and James Baldwin, it was the site of great art and wretched politics, a noisy quietism combined with provincial bad taste, all of which could be redeemed by the ritual. And in our era, when we talk about the black church, we’re mainly talking about Pentecostals.

This was not always the case. For a very long time, most working-class blacks were either Missionary Baptists or Methodists (which is to say, African Methodist Episcopals). But in the early twentieth century, the Pentecostal saints marched in and eventually swept all before them. Charles Fox Parham, a Kansas evangelist who made glossolalia — speaking in tongues — the centerpiece of a new faith, is usually identified as the movement’s father. In September 1900, Parham installed his congregation in a rambling house on the outskirts of Topeka, where they prayed incessantly for the Holy Spirit to descend and speak through them. A few months later, a breakthrough came. As a Chicago newspaper summed it up: occupants of topeka mansion talk in many queer jargons.

Parham and his followers were white. But the next great Pentecostal explosion, known as the Azusa Street Revival, originated in a black church in Los Angeles. The pastor of the ramshackle structure at 312 Azusa Street, William Joseph Seymour, had earlier been one of Parham’s acolytes, studying at his Bible school in Texas. His impact, however, far surpassed that of his mentor. The Azusa Street Revival began in 1906, and the ecstatic worship continued in waves for several years. Azusa drew believers from all over the globe, who proceeded to colonize the world for a Jesus who could heal the sick, raise the dead, and unmistakably signal his presence with the gift of tongues.

Glossolalia was not unknown in America: Quakers and Mormons had been speaking in tongues for years. Likewise, the old-time religion goes back much further than 1906. The term “holy rolling” dates from at least the 1840s, and during that century’s frontier revivals, pioneers frequently boasted of getting drunk in the spirit. Azusa’s distinction was its array of races and nationalities: its worshippers arrived from Memphis and Oslo, Alabama and Ukraine.1 Indeed, a 1906 article in the Los Angeles Times recoiled at the “disgraceful intermingling of the races” at Azusa, an extraordinary sight in America at the zenith of the Jim Crow era.

But there were other objections as well. Parham went to his grave dogged by accusations of pederasty, mostly on the basis of his arrest in San Antonio, Texas, in 1907 for what appears to have been “the crime of Sodomy.”2 To this day, many black people also assume that he and Seymour were lovers, simply because no other such close association of black and white men was imaginable, then or for decades to come. To complicate matters further, Parham was a racist; he would later deplore Azusa’s spiritual miscegenation, complaining that

a white woman, perhaps of wealth and culture, could be seen thrown back in the arms of a big “buck nigger,” and held tightly thus as she shivered and shook in freak imitation of the Pentecost. Horrible, awful shame!

Perhaps because of their extravagant piety, Pentecostals were seen as less than manly. For many years, Baptists and Methodists looked askance at them, even as they were unable to resist their music, the rollicking rhythms that would ultimately seduce the world. And eventually, rituals that were considered comical, if not half-mad, became commonplace in all the denominations. Long before the charismatic movement enabled white Anglicans and Catholics to speak in tongues and gyrate in the spirit, black Baptists and Methodists had gotten on board.

There is an additional reason for the special if often subterranean relationship between gay men and women and the Pentecostals. It was not only the drama, the spectacle, that drew them to the church: it was class. For generations, poor gay boys have flocked to Pentecostalism — the denomination of the working class, along with Roman Catholicism — because worship therein allowed an intensely expressive devotion that would be frowned on anywhere else. The outside world shamed or spurned them. In the church, they were welcomed, and their talents applauded. A boy could sing like a lyric soprano and not be dubbed a punk but informed that his rare voice denoted a special anointing. The pastors would praise and the mothers (especially the mothers) would rejoice.

“It’s always been that way,” says the Reverend Carl Bean, a former Motown and disco performer who founded the Unity Fellowship Church Movement in 1982. “The straight boys who play around with girls and make babies and break their mamas’ hearts, they live in the streets. The well-behaved boys, the sensitive, quiet kids, the ones we now call sissies and nerds — they’ve always landed in church. Church or street, take your pick.”

The church has often responded to these sissies in its bosom by reasserting its masculine character. This tendency goes back to the nineteenth century, when the abolitionists and Transcendentalists were dismissed as effeminate and the vigorously aerobic movement known as Muscular Christianity flourished, first in England and then in the United States.

To some degree, though, these fellows have fought a losing game. Pentecostalism in particular prizes its women. The first member of Parham’s Kansas congregation to speak in tongues was a woman, Agnes Ozman, which created an enduring archetype: the male prophet and his perfected female vessel. Pentecostal women have also been among the faith’s most famous evangelists, in both black communities (from Elder Lucy Smith to Prophetess Juanita Bynum) and white (from Aimee Semple McPherson to Katherine Kuhlman). The church may have been the first institution to demonstrate a lasting truth: whenever women assume power in an emancipated, nonsexual way, gay men will be their most ardent supporters.

Nowhere has this truth been proved more consistently than in the world of gospel music. As I have noted before, gospel has long been a gay genre — one in which male singers would “mock” (that is, copy) every vocal habit of the female singers they worshipped. The exchange worked both ways, allowing men and women, gay and straight, to draw on each other for inspiration, creating a music filled with male sopranos and female basses.

Mahalia Jackson was early and always the queen of the gay singers and groupies — the Children, as they were called. But her only rival, Marion Williams, may have been more instrumental in bringing this cross-dressing style to the masses. She invented a startling mix of growling syncopation and ecstatic falsetto, her high C’s derived more from field hollers and electric guitar than the opera stage. And her greatest imitators were men. Little Richard, the so-called architect of rock and roll, copped his style from her. And his acolytes included James Brown, the Isley Brothers — and, just a few years later, the drag queens of Stonewall, strutting through Greenwich Village with an approximation of Williams’s generous hips, greeting the straight world with her patented “whoo-hoo.”

That’s an awful lot of American culture changed for the better by the union of strong women and their gay disciples. And within the black church, nobody complained, since they were too busy rejoicing. The great world, however, was sometimes less welcoming. Remember the hostility toward disco, a music dominated by gospel-lite divas and their gay fans, who had adapted their church dancing for the club.

Or think of Billy Preston’s hard times. He was a superb musician, who cut his teeth with Sam Cooke and Ray Charles, and was temporarily dubbed the Fifth Beatle during the Let It Be sessions. But when the gay Preston danced his way through “That’s the Way God Planned It” during his tours with the Rolling Stones, one rock critic grumbled that he was a “showboat.” (So much for Mick Jagger and his Tina Turner moves!) Such critics willfully ignored that Preston was gospel’s ambassador to the world of British rock, which couldn’t have existed in the first place without the church and its gays.

It was, in any case, the Pentecostals who won the sectarian battle. For years, they had been ridiculed as the lowest of the low, the crazies who spoke in unknown tongues and held themselves aloof from this world and its woes. (“They can’t even dress right” was a familiar complaint.) But by the 1970s, the leading black Pentecostal denomination, the Church of God in Christ, was outdrawing the Baptists and Methodists, many of whom had begun tongue-talking and faith-healing themselves. Some who had once mocked the saints now started calling themselves Full Gospel Baptists; others invented a telling portmanteau, “Bapticostals.”

With tongues, you could speak directly to God in your own private language or, even grander, have him speak through you. No earthly power could contend with that. Yet some pastors were not quite so oblivious of the world: they wanted a piece of that power for themselves. Jimmy Swaggart, Pat Robertson, and Jim Bakker became the ascendant figures in the white Pentecostal church, and merged the faith with conservative politics. On their television shows, such as The PTL Club and The 700 Club, viewers were exposed to a continuous stream of right-wing boosterism. Swaggart became an advocate of Pinochet’s Chile, while Robertson, who seldom encountered a dictator not to his taste, formed a special friendship with the Guatemalan leader (and Pentecostal) General Efraín Ríos Montt.

These men’s politics didn’t hurt them at all in the black church. This shouldn’t have been a surprise: the church’s politically progressive wing, represented by Martin Luther King Jr., had collapsed in the wake of his assassination in 1968. After his death, his spirit was occasionally invoked with the anodyne command “Don’t let the dream die!” But a larger perspective was slow to evolve. And if black Baptists tolerated the icons of the religious right, black Pentecostals treated them like heroes. When Robertson ran for president in 1988, he was immediately endorsed by the Church of God in Christ, just as George W. Bush would be endorsed in 2004 by the kings of Detroit gospel, Bishop Marvin Winans and Pastor Donnie McClurkin. What these gentlemen admired most was Bush’s opposition to gay rights, which they probably hated more than he did. And they were nothing if not consistent: in 2012, Winans advised his flock not to reelect President Obama because he had by then endorsed same-sex marriage.3

The Pentecostals continue to delight in their holy boldness, defying sense, sensibility, and their own people’s history. Thus, a black Chicago pastor has boasted that he would ride with the Klan if it opposed gay rights. A black Florida evangelist with a taste for exorcising the demon out of gay people praises God for slavery, since it proved the conduit to her salvation: “Without slavery, I would have died a wretch undone.” James Meeks, a state legislator and pastor whose Chicago church was once regularly visited by Senator Barack Obama, used to rage against “Hollywood Jews for bringing us Brokeback Mountain” — and, during an unsuccessful political campaign, this black preacher declared that he was the only true “white conservative” in Greater Chicago. And there is Carol M. Swain, a professor at Vanderbilt and vigorous opponent of Black Lives Matter, which she has denounced as a Marxist plot. When this ardent Pentecostal booster of Donald Trump was asked about David Duke’s endorsement of her candidate, she described it as a “nonissue.”

It should be noted that the worldwide triumph of Pentecostalism is indivisible from the success of the prosperity gospel, a trope invented by the Reverend Kenneth Hagin. Very simply, it proposes that God wishes abundance for his flock, and that it is theirs for the asking — and for the tithing. (“How do you get more?” asks the local bishop, followed by laughter. “Baby, you give more!”) In other words, to paraphrase Milton, they also gain who only stand and wait. That the prosperity gospel doesn’t seem to work — that African Americans today have failed to make those promised financial gains — has not yet sunk in, and may not for years to come.

Virtually all the mega-pastors subscribe to the prosperity gospel’s tenets, revealing themselves as arch-capitalists even if the rewards come by faith (and not, as the Scripture says, by sight). The biggest prosperity pastor is the wondrously named Creflo Dollar. And perhaps because the pursuit of wealth may seem shallow, the prosperity crowd has found one sure way to keep firing up the congregation: the antigay passages in Leviticus and Romans have become almost more popular than John 3:16.

The Pentecostal Church was never completely welcoming to the Children, of course. (Neither, for that matter, were the Baptists or the Methodists.) But it wasn’t entirely blind. You couldn’t call it a closet when gays were so conspicuous in the pulpit as well as in the choir. Even the satirizing of gay congregants, frequently by themselves, was almost a family joke — the equivalent of joshing your obese aunt or balding uncle, with no harm intended.

But first AIDS decimated the church, killing its icons left and right. And then the best-selling On the Down Low (2004) revealed that a multitude of “straight” men preferred to meet their tricks in church, after which they might well infect their unknowing wives. And suddenly it became almost obligatory for mega-pastors to deplore gay people. It was hard not to be astonished by the punishing vulgarities, the trash talk, the endless recycling of Yeats’s cosmic joke about love and shit being next-door neighbors.

No sympathy or compassion was extended, no acknowledgment of the immense contributions of gay people. Even as the inevitable song in black congregations became “I Won’t Complain,” nobody mentioned that it had been popularized by the Reverend Paul Jones, killed at the age of thirty after a date gone terribly wrong. Instead the homophobia flowed like holy wine, frequently observed without critique by outsiders.

Thus Kelefa Sanneh could write in a 2004 New Yorker profile that although Creflo Dollar was “unswerving in his denunciation of homosexuality,” he was also “careful to avoid the kind of inflammatory language that potential followers might find offensive” — as if his homophobia were simply something to be finessed. The church’s most tormented self-hater, the unabashedly ex-gay McClurkin, nearly cast a pall over Obama’s campaign in 2008 when his record of attacks on gays (“vampires,” he called them, in their pursuit of black children) was revealed. Yet Nate Chinen responded equably in the New York Times that McClurkin “overcame great adversity to become a role model.”

Of course, white Pentecostals have held their own when it comes to the mangling of history and spiritual decorum. Lou Engle, a white televangelist pastor, has urged God’s people to rise up the way Robert E. Lee rose up against Lincoln. Lee “had an anointing or something,” Engle declared during the Christian Broadcasting Network’s 2012 Week of Prayer — and he also invoked Stonewall Jackson as an inspiration to antigay crusaders, who were exhorted to “raise up a stone wall to restrain the agenda that is coming out of D.C.” His black allies didn’t chastise him.

Nor did they object to the looniest and most lethal of these revisionists, a white man named Scott Lively, who argued that Nazism was actually conceived by homosexuals. Lively went on to become among the first to colonize Uganda for the international war on gays. He has dwelled at great length, and with a kind of lip-smacking obsessiveness, on the connections between homosexuality and coprophilia, illustrating his lectures with visual aids. Thus do we have the likely inspiration for that piquant line uttered by the Ugandan pastor Martin Ssempa: “The gay people, they eat the poo-poo.”

When it came to contemporary gay-baiting, nobody was as persistently on the rhetorical prowl as Bishop Eddie Long of Atlanta. He was a new-breed Bapticostal, known for looking smart, smelling fresh, and showing off his gym-toned body. Asserting a twenty-first-century form of Muscular Christianity, he hailed his butch parishioners, the “shorties” and “sporties,” while perpetually damning his gay congregants. In 2004, he led an antigay rally at Martin Luther King’s grave with King’s daughter Bernice, who claimed to channel her slain father: “I know from the depth of my sanctified soul that he didn’t take a bullet for same-sex marriage.”

When Coretta Scott King died in 2006, homophobia haunted her funeral too: there was Bernice conferring with Bishop Long near the altar while her siblings, who’ve supported gay rights, sat in the congregation. (An outraged Julian Bond refused to attend the service.) A similar claque dominated the funeral of Whitney Houston six years later. The singer’s mother, Cissy Houston, recruited the church’s biggest homophobes to officiate: T. D. Jakes, McClurkin, Winans. Meanwhile, Aretha Franklin was not present. She chose during her concerts to have the deceased commemorated by Carlton Pearson, the prophet of an inclusive ministry in which gays and lesbians do not end in a fiery hell.

In the face of such cycles of hypocrisy, a good laugh could prove redemptive. After Bishop Long was outed and accused of sexual assault by five of his young parishioners in 2010, spandex-clad selfies of the buff pastor appeared on the internet. Was this how Muscular Christianity would end — dethroned by a cell phone? There were rumors of a multimillion-dollar payout, and Long stepped down from his duties. But he returned in early 2012, welcomed back to the pulpit by a self-styled Messianic rabbi who wrapped the penitent in a Torah scroll.

You could say that Long had forgotten the Bible’s warning that if you cover your head, your feet will show. Ben Carson, the erstwhile candidate for president and at this writing a prospective member of the Trump Cabinet, may have overlooked that lesson as well. His homophobic pieties are delivered in a gentle murmur — but his adviser Armstrong Williams is a more strident figure, the Eddie Long of business consultants. Williams is a devout conservative and antigay warrior, who was nonetheless sued in 1997 for hitting on a male colleague and attempting to climb into bed with him during business trips. The suit was settled out of court, but other men have made similar claims about Williams, including the G.O.P. apostate David Brock, who was reportedly asked by Williams whether he was “dominant or submissive in bed.”

At least one part of the Pentecostal war on gays shows some sign of flagging: 2013 saw the collapse of Exodus International, a group of charismatic Christians (i.e., middle-class Pentecostals) who had long proclaimed that prayer and psychological counseling could “break the yoke” of homosexuality. After thirty-seven years of such curative efforts, they finally concluded that 99.5 percent of gays would never change. Now they admitted, half-sheepishly, that they had betrayed thousands of innocent lambs. Though he apologized for any hurt feelings, the organization’s leader, Alan Chambers, refused to acknowledge the torments unto suicide that the group had induced. Nor did he offer any retroactive comfort to the flock, who were expected to lead sexless lives — their particular cross, the old hymn having assured us that everybody needs at least one.

Still, many of the hardcore Pentecostals remain committed to this mission. (Mike Pence, our new vice president, has also expressed his enthusiasm, at least in the past, for organizations providing “assistance to those seeking to change their sexual behavior.”) Gays, such believers insist, are only a few prayers away from complete deliverance. To catch these Yoke Breakers at their most raw, watch the YouTube video of a revival held at a youth center in Alabama called the Ramp. It features a young pastor — dressed, comme il faut, in the style of a Seventies rocker — excoriating the media’s embrace of those diabolical gay people. He commands all those struggling with same-sex attraction to rise and be healed. Down the aisles they run, girls and boys, demonstrating how many gay kids must fill those Southern churches. They fall on the altar, weep and collapse, slain in the spirit, desperately awaiting the one touch that will never come.

It is a glib fallacy to say that Sunday is the most segregated day in America. If anything, that’s when the Anointeds — the most strident fundamentalists, black and white alike, each of them confident that God speaks to and through them — act in concert.

Church is church is church. The dynamics I have addressed above obtain anywhere and everywhere. In the 1930s, Father Charles Coughlin terrorized the nation with his right-wing politics. Viewing his rallies in old newsreel clips, you see a glowingly confident performer, speaking directly to a flock of tough, handsome youths — it’s an uncanny anticipation of an Eddie Long revival. And sure enough, Coughlin was silenced only when the FBI threatened to reveal his homosexuality.

The white Pentecostal church is as quietly queer as the black. In Nashville, it is assumed that country gospel cannot exist without gay pianists and composers; awards ceremonies are celebrated all over town with “Pink Nights.” Lonnie Frisbee was indeed the original Jesus Freak, as T. M. Luhrmann noted in a 2013 article for this magazine — but he was also a gay man, completely ostracized by his own congregation as he lay dying of AIDS.

Ted Haggard, of course, was the most important Pentecostal in America until his public disgrace in 2006. Several critics unfamiliar with the tradition thought that Haggard was an outlier — a naïf who might well convince himself that God wouldn’t call him gay simply because he paid men to have sex with him. But that is a patronizing view of human beings and of their most intimate knowledge.

Haggard was no more a naïf than Matthew Clark, the pastor of the Blessed Assurance Temple in Bartow, Florida. A glance at any video clip of the church’s services will carry the viewer straight back to the nineteenth-century Great Awakening, in which pioneers dashed through the woods, barking the devil up a tree. While the simply dressed and generally obese parishioners at Blessed Assurance run, dance, and speak in tongues, one muscular lad literally hops around the church. Clark presides, looking like a cross between Burl Ives and Andy Devine. Yet he knows all about the local cruising grounds at the Peace River Park, where he was picked up during a police sting in 2012.

It would be a sign and a wonder if gay people, the church’s most devoted members, would prove the means of its destruction, or at least its irrelevance. But that presumes the disappearance of the Anointeds. Instead they congregate in amazing divisions, a little like the individual nations contained within the Hapsburg Empire. Catholics once despised Protestants, and Pentecostalism is the most extreme version of Protestantism, with each saint a pope. Now, in Catholic strongholds like Brazil, the populace is prone to dance and tongue-talk in mass assembly, praying for prosperity and the disappearance of homosexuality.

Equally striking has been the rapprochement between Pentecostals and ultra-Orthodox Jews. But it makes a certain kind of sense. Pentecostals think that fifteen hundred years of Catholicism was a terrible aberration, and that they are the true descendants of Christ’s disciples. Messianic Jews share this conviction. If they infuriate their families by declaring themselves “completed Jews,” they simply honor Christ’s command to forsake one’s “houses, or brethren, or sisters, or father, or mother, or wife, or children, or lands, for my Name’s sake.” Orthodox Jews sit shiva for their lesbian daughters, just as Pentecostals drive them away from home. And since “God Don’t Never Change” (as Blind Willie Johnson put it in 1929), the Old Law is as eternal as the New, meaning that gays are indicted by both testaments.

Sanctified homophobia knows no borders. The legislator and gay-hating evangelist Eduardo Cunha was set to dominate Brazilian politics until money-laundering charges drove him out of office. Many Eastern Europeans have been quick to join the same international chorus — homophobia seems to have replaced anti-Semitism as the great bridge-building passion among Ukraine’s Pentecostals and Russia’s Orthodox believers. Indeed, the Orthodox prelate’s love for Putin recalls the ardor of, say, the pastor John Kilpatrick, who was so uplifted by Trump’s victory that he spoke in tongues on camera.

There remain some brilliant people — Marilynne Robinson is a familiar example — who don’t want to forfeit the splendors of their faith. They deplore the Holy Ghost fascists but consider them ultimately irrelevant to the kind of thinking that animates their lives. But how do a hundred thousand Unitarians, or even 3 million Congregationalists, speak power to half a billion Pentecostals? One thinks of all those Marxist intellectuals who deplored Stalinism but were invariably tarnished by association with the grinding actuality of Communism. For the most part, the Anointeds have now commandeered the word “Christian.” For a progressive believer, the very name has become a burden, another cross to bear.

But even without the Anointeds, the enlightened believers have a most problematic text to live down. I’m always caught up short by thoughts of the vast throng John saw on the Isle of Patmos, described in gospel parlance as “the number that no man could number.” For me, that includes the many millions of ruined gay lives, along with the countless armies of men slain as punishment for their nature. I came late to this knowledge, and only after I produced my first album, a 1973 salute to the gospel songs of Thomas A. Dorsey. I had hired three musicians for the sessions, including Dorsey himself. I heard later that both of the younger pianists were killed by their trade. After that, it was a constant theme — a musician would miss a session, disappear, invariably followed by the bland report: “Somebody killed him.” These black gay corpses may far outnumber the four thousand or so lynching victims, scandalous as that figure remains. The deaths — unreported, unlamented, often unnoticed — occur throughout the world, easily dismissed as a minor sort of collateral damage.

Who could have forecast the reversals, the echoes, the cross-racial patterns that have distinguished this dismal history? But just as right-wing black pastors contemplate marching with the Klan, black and white proponents of gay rights have made some unlikely alliances of their own. In Georgia, shortly after Bishop Long’s disgrace, a white Pentecostal pastor named Jim Swilley outed himself, tormented by the idea of gay boys bullied to death by his coreligionists. When the Maryland legislator and pastor Emmett C. Burns Jr. attacked a black football player named Brendon Ayanbadejo for defending gay men, he was called out in turn by a white player, Chris Kluwe. Perhaps the most amazing alliance was Jason Collins’s identification with Matthew Shepard, heartbreaking in its affiliation of a top jock with a designated faggot.

Some of the boldest voices were themselves former members of the Pentecostal flock. In February 2012, a Marine sergeant named Brandon Morgan became a YouTube sensation when a bystander photographed him rushing off a plane from Afghanistan to embrace his husband-to-be. Morgan, as he later revealed, was raised in the church. He had previously married a lesbian, dreaming that both had been delivered from the demonic Jezebel, that Old Testament vixen about whom the gospel quartets used to sing:

Nine days she lay in Jerusalem’s streets,

Her flesh was too filthy for the dogs to eat.

Even more remarkable, especially in the face of continued resistance from the Pentecostal multitudes, is the liberation being achieved by African Americans themselves. In 2012, it was noted that black people identified themselves as L.G.B.T. at a higher rate than whites or Latinos. (One recent survey indicates that as many as 50 percent of millennials consider themselves not totally heterosexual, which suggests that the church has been suppressing a number truly beyond number.) If you attend New York City’s annual gay-pride march, you will see thousands of black women and men who look exactly like the choir members they probably once were, or still are. They are the ones now holding the fort — the ones who sang the hymns and learned the score.

But the most thrilling instance of young gay people speaking truth to power occurred in 2013, when the Black Lives Matter movement was largely conceived and directed by lesbians and gay men. It was by no means inevitable that B.L.M. would become the focal point of an entire nation’s outrage over racial injustice. In Baltimore, after Freddie Gray’s death, some of the loudest cries of outrage came from a Bapticostal reverend, Jamal Harrison Bryant. “I don’t know how you can be black in America and be silent,” he told an impassioned crowd at Gray’s funeral. “With everything we’ve been through, ain’t no way we can stand to be silent.” Yet Bryant had already forfeited some of this moral high ground with his antigay sermons, which have racked up tens of thousands of views on YouTube.

Instead, the movement’s male voice became DeRay Mckesson, who has made it very clear that black lives mattering means that black gay lives matter, too. He would include his own. After Mckesson’s sexual preference was reported, he received a large number of murderous tweets — and went on to block some 16,000 users, as if to say, Get thee behind me, Satan. Recently, he came up with a new formulation: “Some people are coming out of the quiet, not the closet. Simply because you did not know did not mean they were hiding.” He could have been describing generations of the Children, always in plain sight, even when the church they built turned so viciously against them. Their songs had been heard, if not their stories. Even Billy Preston, who died in 2006, showed his hand toward the end. No longer able to rise and shout, he would announce from his Hammond organ, “That’s the way God wants me to be,” the italics audible for all those with ears to hear.