This is the story.

Kim Le Bouedec and I run the Finchley Mint. And I’ve just kissed his wife.

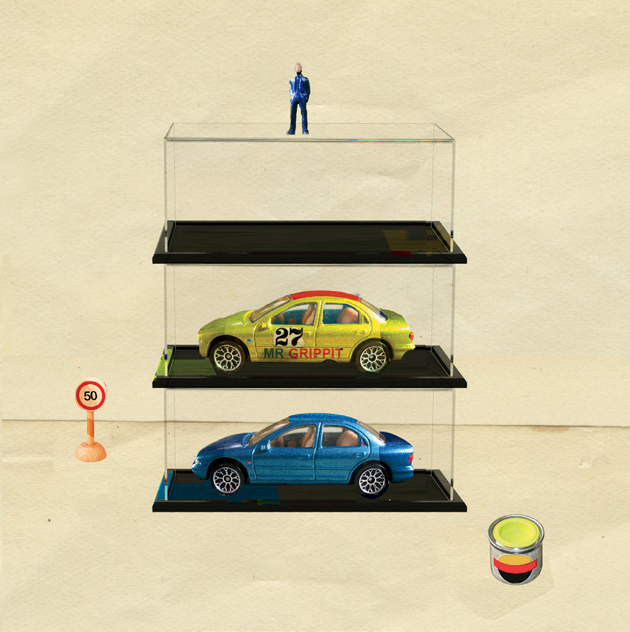

We sell die-cast model cars by mail order. Don’t laugh, it’s a serious business. We always knew, Kim and I, in the years he was at Credit Suisse and I was bumping around the Home Counties in a maroon Vauxhall Insignia, urging skeptical Pakistani pharmacists to stock Dr. Schoepke’s Dynamic Night Conditioner, that we’d end up working together. Our kind of friendship, a perpetual suspension of unctuous love and vinegar, has always made for fun, and for efficiently nuanced exchanges, especially when agitated. And here we are, almost ten years out of college, just on the brink of really disliking each other, with a little business to call our own. Stock-Car Superstars at the Finchley Mint: “You can almost hear the engine rumble.”

The idea is simple. Back in February, when he was still at Credit Suisse, Kim had lunch with Eric Fennema, a fellow Harrovian and colleague specializing in the pharmaceutical industry. Eric had got wind that one of his clients, a health-care multinational, had wanted to reward its 10,000 reps worldwide with a scale model of the standard fleet Mondeo, 1:18 on a lacquered plinth, with a tiny box of nonprescription drugs inside the working boot. But the die-cast factory stipulated a minimum run of 20,000, and now the surplus was going for a song. Within six weeks, Kim had worked out his notice and set up the Mint in the garage of his mews house in Finchley. Now, Kim is one of those omnivorous and preternaturally retentive sports fans whose knowledge extends not only beyond rugby and football and cricket to volleyball and real tennis and pelota and pro mah-jongg, for all I know, but also into the most abstruse and abysmal detail, the tactical peculiarities of the South Korean Olympic curling team, that sort of thing, so naturally he knew a thing or two about saloon-stock-car racing. First, that it is, in fact, arguably no longer a minority sport, with fans in this country ranging from 90,000 to 150,000, and upwards of 2 million worldwide. And second, that the world champion, the U.K.’s own Willie Webster, drives an electric-blue Mondeo Zetec, number 608, gold-roofed to crown him king.

The numbers augured well. Oval stadiums like Billericay RaceWorld, in Essex, can seat, what, eleven, twelve thousand, and when the Texaco Racewall in Canning Town is finished next spring it’ll have a paying-punter capacity of nineteen thousand, plus fifteen hundred more in the corporate boxes. Because what do people want to see, when five days a week they’re stung for tolls to crawl past speed cameras into twenty-mile-an-hour zones, ringed by the new London orbital of congestion-charge avoiders, lulled in their air-conditioned cells by the weather report or an audiobook? What’s the flip side of their tailback trance? A good burn. A crunchy pileup. The popularity of stock-car racing is the natural expression of the average driver’s unmet need for speed. I mean, I can’t say I’m a great fan, but then I’m not an average driver. These stock-car guys, they’re not interested in precision. It’s not like Formula One. They’re not interested in driving — but then neither’s the average driver. So I could understand the appeal, and that it’s an ever-expanding market to exploit.

Which Kim saw straight off, sitting at lunch talking money.

So we signed Willie Webster. At some conurbation-size factory in Kowloon, our Mondeos could be resprayed, stenciled, dented, fitted with custom bumpers, and the brass plaque saluting the Concura sales force replaced with one bearing Willie’s battle cry, “Who do you think you are, Willie Webster?” And then, two weeks later, two days after the decal designs had gone off to Chris the Printers, Webster was forced to renege by his sponsor, a well-known lubricating-oil company I’m bound by law not to name. They said it wasn’t their policy to endorse products at one remove, i.e., our replica 608s. A complete and unexpected U-turn, in other words, and if not an outright lie then at least a fuzzy area of policy, but which given their corporate muscle was just not worth getting litigious over. So we cut our losses and started looking for someone else.

An anxious flick through Oval Racer identified just two other Mondeo drivers on the saloon circuit: Mick Parrott and Jason Skoyles. Mick won the Welsh in 2012 but we opted for Jason — a red roof with flashing amber lights, two grades down from Webster — who at nineteen was already three-time holder of the Hampshire title and hotly tipped by Oval Racer to be this year’s national points champion, winner of the silver roof and a place in next year’s World Championship. Besides, Skoyles is a looker, the little bastard, six foot three, blond curls, bright tenantless smile, the sort of creamy kid to whom you’d hesitate to ascribe star quality, for fear of souring him, but who has it, helplessly, in spades. God forbid he ever meet Jill. Or Sasha, for that matter. Plus, his Mondeo is yellow, a cheaper paint than electric blue, and when his sponsor, Mr. Grippit Powertools, agreed to cover the cost of the decals, the decision was kind of made for us.

We had our stock-car superstar.

And you know, I was glad. Because things hadn’t been going so well for me. I hadn’t thought hitting thirty, a nonevent, celebrated in my friends’ cases with equal parts resolution and dread, would have any effect on me whatsoever. And yet there I was, thirty-and-a-bit, disinterestedly promiscuous, underpaid, as ever, by undynamic Dr. Schoepke, but feeling it all of a sudden, the shame of slow progress, of lagging behind. And then two things happened. One, I met Jill, who, it has to be said, did a lot to restore my confidence, if nothing else by her persistence in me, and to help me respond in the right way to the second thing, Kim calling out of the blue to offer me the job as his partner and marketing manager of the fledgling Finchley Mint. So with Jill’s encouragement I said Auf Wiedersehen to Dr. Schoepke and Oui, s’il te plaît to Kim the very next day. Not least because I could see right then that, over time and handled right, this was an idea that could make us some money, real money, different from the scraps that in my twenties had shot soaplike through my scrabbling hands, money that might sit and grow and give me the heft to contend with bigger things than rent and bills and whose round next.

And business is fine. Gli affari non vanno male. With the retail price set at £49.99 (or three monthly installments of £17.99), sales are projected to reach just under half a mill by year-end. There have been problems, with the product, and with Jason Skoyles, but things have taken a turn for the better. And besides, it’s problems — resistance, the pinpoint proximity to getting it wrong — that goad the will on to surmount them. Perhaps I mean that it’s problems that goad on the will to do anything. A sort of feedback loop driven by its own difficulty. With a bit of push, and the kind of luck we had last night, you can outmaneuver anybody. And, in any case, Kim and I have evolved a working method, based as I say on our special Anglo-French, best-enemy relationship, that allows us to share the responsibilities of, for instance, maintaining the systems for order fulfillment, Kim to take a clear strategic lead, and I to flirt as much as I like with his wife when he’s not looking.

I know what you’re thinking.

But I know what I’m doing. We won’t get caught, not if we’re precise about it. Sasha and I go back a long way, we know each other’s ins and outs. From back when everyone was . . . I mean, one night, after two E’s and a gram of coke, I almost fucked Kim. Of course things are different now. Of course now my friends are married, there are kids at stake, the borders are properly policed. Although that’s half the point. And listen. Kim’s good brain is distinguished more by its storage capacity than its processing speed. You only have to watch him talking business, with Eric, or with Nagesh at the bank, taking in their data, to see what a sponge he is. A great porous monolith of linen suit and pockmarked skin, topped by the lintel of a frown of profound interest: Kimhenge. Absorbing and storing as thoughtlessly as stone. That’s what Kim’s love for Sasha is: stored warmth, slowly released. And meanwhile, out in the quick cold, Sash and I have been having it off for years, in squirreled looks, foxy comments, swift collisions. In a hushed but persistent promise: one day.

But I have to say what happened on Friday night I was not expecting.

I’m not an adulterer yet. But I will be, and soon. I can feel it coming on like autumn. Can’t you? Ever so slowly, a chill in the bones, and then suddenly, snap, you’re huddled against discovery? How old are you? You see, this is the paradoxical thing about my peer group (and yours — if it hasn’t happened yet, it will). The more we settle, the more opportunities there are for disruption. Because adultery’s just not adultery when you’re still fucking around (adultery’s not adultery when nobody’s married). My London was once a network of coupled places; I was aware, driving around, of tenuous cords, like strands of semen, connecting Clapham with Kentish Town, Maida Vale with Barnes, Notting Hill with Whitechapel. A bus map, a Knowledge of coupling: a transport system. Now Simon and Maxine are married with a ten-month-old daughter. Luke, a partner at his law firm and earning a packet, is married to Helen, a fellow marketing manager of Jill’s at L’Oréal. The strands have dried and disintegrated, been replaced — for now at least — by the much flimsier filaments of friendship. We don’t see one another anymore, we keep in touch. Football’s still played some Sundays, but guilty stability’s put paid to the after-match drink — other halves to get home to. Friday nights, by default, are for box sets and takeaways, or, when we do make it to a bar or a club or a party past midnight, are cast in the faint but unmistakable gloom of occasion and achievement. Drugs are now either a habit or only for Christmas. My circle of friends, turning square.

Take the other weekend.

Luke and Helen had rented a cottage near Stow-on-the-Wold for a fortnight, to see, Hel said, what living in the country might be like. Being a salesman-veteran of motorway turnoff, I could have told her: it’s like the town, only lonelier. The laughably pretty village was called Lower Slaughter, which from the hints Luke’s dropped about their sex life was either a cosmic joke or Helen trying to tell him something. Anyway, out of horror at chastity in the heritage belt or nostalgia for the good old days of substance abuse and casual congress, Luke invited six of us up for the weekend — “Plenty of room, double bed, single mattress, two bunks, and the sofa for you, Neil.” No one’s quite got used to me going steady. Because I was the appointed singleton, the exception that proved their lives, lived by new rules, might be viable.

“You don’t want me to come,” Jill had said.

“Yes I do.”

“No you don’t. They’re your friends.”

“Yours too, now.”

“Not in the same way.”

“What’s that meant to mean?”

We’d done this several times before. I knew what it was meant to mean. I also knew what it really meant — what Jill meant by meaning to mean it. She wanted to be pleaded with, prioritized. Who knew if I wanted her to come? Could I enter into the cozy new conspiracy of separate togetherness, for a few days at least? Would it be fun? Good training? Would it make me more or less visible to Sasha? Two options. Either placate Jill — “Please, darling” — and hope she might happily say no. Or affect offense at the aspersion — “Because I slept with Maxine?” (Jill doesn’t know about Sasha) — confront her with her jealousy, dissolve her with a drop of anger, and accept her No, you go as conciliatory proof of her trust in me.

“Look, come if you want to, don’t if you don’t.”

“I’m not sure.”

“Well, I’d really like you to. And Helen will be disappointed.”

“I might just do some things at home.”

“No pressure either way. But it’s okay if I take the car?”

“I’ll come.”

“Really? Good.”

“As long as we’re not back too late on Sunday. I’ve got to go to work the next day.”

So the six of us set off that Saturday morning, two by fuel-uneconomical two. Of course within half a mile of the lifted restriction past R.A.F. Northolt I’d left them far behind — Kim’s bad enough, but Simon drives like an old lady, like Pnin, pulling down on the wheel like it’s the ladder out of a swimming pool. We arrived at Glebe or Glib Cottage or whatever it was called forty-five minutes ahead of Kim and Sasha, twenty minutes earlier than expected, to be met by Luke at the wisteria-wigged doorway, holding a pitcher of mojitos with the liminally hostile awkwardness of a man who knows, Now I’ll have to behave in certain ways. In the background towel-turbaned Helen steamed past unpublicly.

“You’re here,” he said. “Helen’s just having a bath.”

And that kind of set the tone for the weekend. Of it never being quite the right time for anything. Oh, we had a laugh, of course, traded in the cool thin currency of quips and repartee, but don’t you think sometimes that having a laugh is the last thing left, or, rather, an essentially anxious response to the feeling that there’s nothing left, that no one has anything to say to one another? I don’t want to come the misery guts, but it’s not like it used to be, kidding around being one of a number of tones available to our careering improvisations, taking in music and gossip and books and personal histories, stoned riffs starting funny then grading, sometimes, into serious avowal or point of view, then, sometimes, back to funny again. The thing was, it didn’t matter what you said. Now it’s narrower. Now it’s gag or be gagged.

After an insufficiently drunken lunch we went for a walk. A round trip of miles from Burford, along the trickling Windrush and back, up muddy wold and down ankle-spraining scree, seven of us (Sasha napped) strung out along the skyline like the dance of death at the end of The Seventh Seal. Walking. Not talking. Me to Luke: Everything all right with Hel? Luke to me: I’ll tell you later. (He didn’t.) That chat constantly deferred. On the way back to the cottage, perhaps out of an unspoken sense of communal guilt at not having mixed, drivers and passengers played musical chairs: Maxine drove me; Jill drove Simon; Kim, Helen; and so on. That’s as far as it goes these days. We used to see one another’s bedrooms — now it’s the inside of our cars. Maxine, I remember, had a bedroom full of chimes, a furtive lover’s nightmare of dangling steel tubes and dopey-sounding scooped-out bamboo stalks that rang and jangled and clonked if you so much as sat on the bed, and sure enough, here in her Golf, suspended from the rearview mirror, was a cluster of tiny tubular bells, gonged on corners and gear changes by a dolphin on a string.

After an insufficiently drunken lunch we went for a walk. A round trip of miles from Burford, along the trickling Windrush and back, up muddy wold and down ankle-spraining scree, seven of us (Sasha napped) strung out along the skyline like the dance of death at the end of The Seventh Seal. Walking. Not talking. Me to Luke: Everything all right with Hel? Luke to me: I’ll tell you later. (He didn’t.) That chat constantly deferred. On the way back to the cottage, perhaps out of an unspoken sense of communal guilt at not having mixed, drivers and passengers played musical chairs: Maxine drove me; Jill drove Simon; Kim, Helen; and so on. That’s as far as it goes these days. We used to see one another’s bedrooms — now it’s the inside of our cars. Maxine, I remember, had a bedroom full of chimes, a furtive lover’s nightmare of dangling steel tubes and dopey-sounding scooped-out bamboo stalks that rang and jangled and clonked if you so much as sat on the bed, and sure enough, here in her Golf, suspended from the rearview mirror, was a cluster of tiny tubular bells, gonged on corners and gear changes by a dolphin on a string.

“It’s funny,” she said, as we crunched out of the car park, too slow behind Jill, “how all of a sudden we mind our own business. I mean as a group. We used to be so — into one another.”

Now this was more like it. It’s like the intimacy of the car interior, with its cans on the floor, its CD selection (trance-driving standards: Portishead, Massive Attack, Boards of Canada), its whiffs of warm vinyl and baby sick, unnoticed till an alien enters, had eased Maxine into candor. And looking over I thought how easy, how right it would be to direct her into a lay-by, lift up her T-shirt, and run my tongue down her stomach, still ruched from her caesarean, I imagined, like the inside pocket of an old-fashioned suitcase.

“I’m so glad you said that.”

“You know? It’s like this living-in-the-country bullshit. Why? What’s wrong with living close to your friends? They don’t even have kids. And as if you could find out in a fortnight.”

“Well, I don’t think the experiment’s been a success.”

“Whatever, it’s the impulse. A kind of elective provincialism. I mean, I love Luke, but . . . I’m twenty-nine, for fuck’s sake.”

“You don’t want to live in the sticks. Third.”

“What?”

“You want to be in third gear.”

“Fuck off, Neil. I don’t want any of us to live in the sticks. I don’t know. Maybe things aren’t good between Luke and Hel and the mood is catching. It’s just, I love my husband, I love my kid, like I can only hope Sasha loves Kim, and vice versa, and yet we’re all acting like marriage is this fragile state that mustn’t be corrupted by our past.” Ahead, framed in the back window of the Beemer, Simon and Jill sat in silent silhouette. We rode a bump, the wind chimes jangled, and Maxine laughed. “Like Simon minds that you and I shagged.”

In the evening we played Mr. and Mrs. One by one we were sent to the kitchen while the others devised questions to test our partner’s knowledge of our habits, hang-ups, likes and dislikes, and so on. I got:

1. Is Jill more scared of (a) plane crashes; (b) car crashes; (c) spiders?

2. Which would give Jill the greatest satisfaction: getting (a) a gay man; (b) a straight woman; (c) a celibate into bed?

3. Does Jill prefer (a) giving head; (b) receiving head; (c) Radiohead?

The correct answers were (b), (c), (c). I answered (c), (b), (c). One out of 3.

Jill got:

1. Would Neil prefer to be cuckolded by (a) Nico Rosberg; (b) Jenson Button; (c) Jason Skoyles?

2. Would Neil prefer to operate (a) the robotic arm of a submersible sampling extremophiles in a deep-sea hydrothermal vent; (b) a mini-rover exploring ancient Martian lakebeds; (c) a femtosecond laser pulse performing intracellular brain nanosurgery?

3. Does Neil prefer (a) driving; (b) sex; (c) talking about himself?

The correct answers were (b), (c), (b). Jill answered (c), (b), and (b) after half an hour of (c). Two and a half out of 3.

When Sasha was asked, Which would you run back to save if the Mews were on fire — your cello, your wedding dress, or Bizet (their spaniel) — she said the cello without hesitation, Kim having decorously predicted Bizet. Which would have seemed a tease had Kim not looked so hurt, so pulled taut by what was obviously an unexpectedly restive yank on whatever bond still held them together. And although the silence that grew from Kim’s wretchedness was quickly broken by Luke’s call for a spliff to be rolled, all the quicker perhaps for Sasha’s steady smile being generally taken for obliviousness, I think I knew the smile for what it really was: a mark of quiet victory.

The final scores were: Neil and Jill, 3½; Luke and Helen, 5; Simon and Maxine, 6; Kim and Sasha, 4.

The kiss happened like this.

Friday night Kim and I decided to finish boxing up the week’s orders over a few Budvars in the living room. Sasha was upstairs practicing her cello, and as Kim and I sat wordlessly nestling and taping and squeakingly penning addresses, the sweet constricted complaint of some Brahms suite squeezed through the floorboards and swelled down the stairs like overheard carnal moans. Kim, absorbed in his task, didn’t seem to notice, but to me, brow tightened by the evening’s first beer, my eavesdropping felt profane, and I didn’t trust myself not to show it.

“Kimble,” I said — perhaps a little too loud. “Shall we go for a pint?”

“Mnah. Trop fatigué. Stay for supper if you like.”

All I’d be missing was Jill, The Good Wife, and a take-out Thai.

So I stuck around while Sasha, airy in cream linen trousers, breasts belied by a loose-fitting white shirt, knocked up a cinnamony chicken-and-chickpea tagine and Kim showered. We talked, rather desultorily — I found I didn’t have much to say on the subject — about Helen and Luke, who, after their test fortnight in the sticks, had resolved on another experiment: living apart for a month.

“When I think of Luke,” said Sasha, “I think of him looking appalled at the door. Which is why he chose an impossible career bitch like Helen. He knew he’d end up alone. We get what we want, whether we know it or not.”

Supper was delicious. Kim and I talked about Monday’s big race. Sasha ate a small portion, then sat tinking a rhythm on her wineglass with her fingernail, uncomplainingly bored. Under the table, Bizet slalomed my calves and emerged by my chair, begging for bones.

“Sash,” I said, setting down my fork, “you’re a genius cook.”

Sasha clicked her fingers for Bizet. “That’s wonderful, Neil,” she said. “You’re always saying what no one else is thinking.”

Now what did she mean by that?

That I was demeaning her other achievements by touching on a wifely one? That we were still meant to be pondering Kim’s (low) estimation of Skoyles’s chances on Monday, and I’d broken some solemn ruminative spell? That, as seemed unlikely from the near-spotless plates, Kim and Sasha had thought the tagine was disgusting? Or that I’d missed some delicate dynamic, some infinitesimal twang on the couple’s connecting filament, perhaps to the effect that my desire for Sasha was a little less hidden than I meant it to be, and was now being neutralized by open acknowledgment? Or did she just want to fuck me, and was risking an outright come-on in the knowledge that Kim, abstracted at the best of times, was exhausted in the run-up to Monday’s big race?

I didn’t know. I was too taken aback at first, and then, as the possible interpretations budded and branched, too turned on by the ambiguity to ask for an explanation. I still didn’t know an hour or so later, after Kim had gone to bed and Sasha and I had sunk a couple of glasses of Kim’s “special” eau-de-vie, when she put my glass down, led me to the door, gazed past my shoulder, and kissed me, a warm, wet, sliding, exploratory kiss, tasting of pears, which, whatever she’d meant earlier, could only mean intent.

Then she pushed me out into the thrilling night air.

Why do drivers and cyclists hate each other so much? Because each flaunts freedoms the other decreasingly enjoys. The driver to move, the cyclist to occupy space. Such hatred. Because one considers the other an alien, an arrogator, an incorrigible cheat. I mean look at him. Oh, the piety of the Lycra-clad and walnut-bonneted. Look at that preemptively indignant scowl. He’s hanging back in my blind spot so I can cut him off at the turn and fulfill his self-mortifying street-reclaimer’s prophecy. You see there’s no hope of conciliation, because there’s no language in common. I can’t call him a wanker for cycling dangerously because that’s what cyclists do. That’s what bicycles are for: cycling dangerously. I mean bicycles: get serious. What the fuck are they doing on the road? Cyclists. I could kill them.

Well, your time has not yet come, my son. See, even now that I’ve let him pass he can’t resist a look over his shoulder. To let me know that he sees me, that the struggle continues, that one day Christ will arrive on a bike.

It’s 7:26, and I’ve just turned left onto the Upper Richmond Road. The left lane is inching forward but the right is moving much faster. In the mirror a white Transit is bearing down hard, but I decide to risk it. I wrench the wheel and ram the shift into second. Shrug off the howl of his horn as a loser’s boo-hoo. Beat the lights and brake, late and hard, on the turn, wait till the front suspension dips, down to second, release the brake, wait till the suspension rises (absorbing momentum), brake again, release, and off down Putney Hill at forty.

Check the mirror: white van’s still behind me.

In fact he’s so far up my arse I could use his bumper for a mouthguard.

I brake a little to piss him off.

Seven-twenty-seven.

In this traffic, eight, nine minutes to Wimbledon tube. I’ve made up at least three minutes (nice driving) but I’m still late, late, late. I see the road from above, the linked lights, the smooth flow, and the sliding yellow rectangles of Sasha’s train, converging on the same point in space but not in time. I press down on the accelerator and the Transit recedes in the mirror but ah, camera, squeeze the brake. The Transit gets big again. I see Sasha in her shuddering train, dressed in black for a dinner to celebrate her husband’s, and her lover’s, success (and mourn her marriage).

The Mint had been in trouble. We needed to sell 833 units a month, and in the three months following the website going fully order-enabled, we shifted a monthly average of 490. This was down to two factors. Small Miracles, and Jason Skoyles.

Two months after Willie Webster reneged on his deal with us he signed with Small Miracles. So much for no endorsements at one remove. In July the Small Miracles 2016 Official Willie Webster Mondeo Zetec die-cast replica went on sale at the special price of £60. Naturally it got a lot of noise. Who was on the cover of August’s Oval Racer? Willie Webster, holding up a Mondeo, with his arm around Nigel Mansell. Model Car Enthusiast said that the Small Miracles Mondeo was “up there with the immortal 1:24 Dale Earnhardt ’81 Wrangler Pontiac.” And us? We got a mention in Miniature Car Aficionado, published in Ahoskie, North Carolina, and available in selected U.K. newsagents at the think-twice price of £11.95: “Tiny Limeys Shine in Summer Stock-Car Pile-Up.” The Aficionado is half an inch thick and nine-tenths classifieds and so relentlessly, perfunctorily upbeat in its meager few pages of editorial that a thumbs-up — literal, in the case of his byline picture — from editor Jim “Smokey” Turedo is praise in a pretty disastrously devalued critical currency. Observations like “It’s even got an awesome working boot” just wouldn’t wash at the Enthusiast, where a working glove compartment is the very least that might warrant a mention.

Detail. It’s what the die-cast market’s all about. It’s what these get-a-life guys like: being true to life. And this, unfortunately, is where the Webster Mondeo left us standing. Our product is an executive toy. Theirs is a replica. Turn over our Mondeo and what do you see? A flat piece of crosshatched black plastic. Turn over the Webster Mondeo and you see a chrome-plated plastic chassis with exhaust, front suspension, and differential faithfully rendered. The Webster Mondeo has a usable textured-plastic steering wheel, upholstered seats with belts, a removable steel dipstick, and door handles that you can operate with a pen or a long fingernail. Ours has an awesome working boot. Kim has always maintained that we can beat Small Miracles on price, and on branding, that it’s the sports fans we’re selling to, not the die-cast collectors. That, in any case, advances in injection-molding technology have made the most intricate designs easy to manufacture in vast quantities, so the question of what constitutes craftsmanship is more vexed than it was, and what really matters is brand salience through celebrity endorsement.

Which would have been fine if Jason Skoyles were a celebrity.

Over the past three races he had squandered a six-point lead and was now tied for first place with Pip Tinniswood. Andy Craske in the Primera was running a disconcertingly close third. In the world championships, Webster had won five races in a row and looked a shoo-in for a second title. Once a driver’s won his silver roof, he automatically qualifies for the world heats and tends not to compete in the national championships, but he can race as a wild card in the national final, since the championship is won on points. So for Skoyles the coming Monday was not only a close call for the silver roof but his first chance to race against Webster, who, under pressure from his sponsor, had decided to compete.

Kim and Sasha would be tuned to Sky Sports and serving beers and burgers.

On Sunday Jill and I drove to Henley for one of her interminable rambles. Ten miles of trudge and riverine sighs and pledges to learn more about trees. This is the idea: to take our ideal selves for a walk. Our most tender, constant selves, fresh-aired and fit, happy and in love, stumbling over melons into a future as fixed as the path in her Time Out book of country walks.

What a joke.

Since Friday night we hadn’t spoken much. On Saturday we went for a drink in Barnet and Jill kept apologizing for my brusqueness. “Are you bored?” “No.” “Sorry, darling, I’m not much fun tonight.” This is one of Jill’s most maddening skills, her ability to take the blame for everything. Her negative culpability. You have to feel sorry for her. Next to Sasha’s dry mind and sharp tongue, her pushiness, prickliness, resistance; her high resolute breasts, her tight brown skin, her bony shoulders, wide as a crossbow; her faint lemony smell; the fact that she’d married the son of a French millionaire and kissed me; next to these irresistible acuities Jill, to be frank, looks a bit of a lump. And all the more infuriatingly stolid for not finding me out, for not guessing. So why haven’t I told her? Why did I go for the walk? Out of pity? For the drive?

I didn’t even get to enjoy that.

So my second-favorite stretch of the M40, the plunging, sweeping chicane short of Junction 4 (bested only by the — uncontroversial, I’ll allow — classic hurtle through the Chiltern scarp at Junction 6) into the pupil-shrinking plain of Oxfordshire. And there I was, arms locked against the crosswinds, needle lusting for the ton.

And Jill said: “Darling, you’re going too fast.”

Can you believe it? On one of my favorite stretches? For which you might as well substitute the, I don’t know, A4130 from Maidenhead, if you’re not going to take it at speed? It’s a BMW, for fuck’s sake. Have you felt, against your foot, at ninety-five in sixth, the sphincteral resistance of torque in store? I’m a good driver. And you want me to slow down?

“Am I? Why?”

“Because I’m scared.”

“Why weren’t you scared at ninety?”

“Because we’re on a bend.”

“There was a bend at Beaconsfield. I took that at eighty. Do you think we would have survived an eighty-mile-an-hour crash?”

“I don’t know, Neil. I’m just scared. Please.”

“But the road is clear.”

“Please, darling.”

“It’s safe.”

“Neil.”

“Fucking hell.”

I wanted to say to her: It should be a pleasure to be driven by a talented driver. But I couldn’t say that, could I? You can’t say that sort of thing.

“It should be a pleasure to be driven by a talented driver.”

No answer.

What was I doing with her in the first place?

In a way, yesterday’s, Monday’s, gathered crowd presented an awful, alluring opportunity to tell everyone that Sasha and I were about to embark on an affair. All the old friends in one room, with only one notable exception. Luke had come without Helen. More than ever he looked awkward, empty, full of nothing to say, I guessed less out of marital grief than that, abandoned, he’d had a few weeks on his own and grown used to it. And of course without Helen to drive him home plastered he couldn’t seek his usual refuge. Still, the rest of us were relieved not to endure Helen’s stultifying shoptalk, her smug pronouncements on branding, her condescension to Jill (which Jill is too meek to admit). Simon sat with little Alice on his knee, and, jigging her into giggles, held Jill and pregnant Lara hypnotized. Everyone (but Luke) seemed unusually calm, voluble, humorous; despite the wedding rings and baby gurgles it felt, for a while, a bit like the old days. Downstairs the Mews is divided into an office garage, a kitchen, and, at the foot of the blond-wood spiral staircase leading to two bedrooms, a large, light, largely empty living room, with whitewashed brick walls and shuttered French windows that open onto the cobbles outside. It was odd to see this airy space, through which I often imagine that on solitary afternoons Sasha moves like a crisp shadow shifted by the sun, busy with people. Three walls are hung with abstract seascapes (I suppose), rendered in hard-edged gray and white, and the fourth with Kim’s fifty-inch wide-screen TV, almost flush with the bricks. Once everyone had a burger we settled down on the sofa, the floor, and the pair of 1950s red-vinyl barber’s chairs I’ve never quite had the nerve to disparage.

The TV showed a long shot of the cars, revving on the floodlit grid under the dark dome of Billericay RaceWorld. Kim turned up the volume, and what had been an undifferentiated din split into the snarl of the cars and the cheers and jeers of the crowd. Obscuring three or four rows of twenty seats each was a crudely daubed banner proclaiming willie power. We all booed. Then the camera cut to a mid-shot; Lewis, crouched closest to the screen, spotted a placard marked skoyles is sex on wheels, and we all cheered, Sasha, thin arms pistoning, inserting a game I agree.

Suddenly, like a shock you’re expecting, there came a swelling frenzy of revs. My stomach thundered, and feeling oddly queasy I put down my burger, a once-bitten U, unwanted.

“Come on Skoylezayyy,” said Lewis, through a mouthful of his.

Later, after Luke had slunk off sober, Alice had been put to bed in the spare room, and Kim had opened a bottle of never-to-be-opened Krug, to celebrate Skoyles’s silver roof, Lewis produced the damp remnant of a gram he’d had in his wallet for three weeks. To the eight of us who didn’t abstain he meted out a line scarcely longer than the sort code on his debit card. I sniffed mine up, and as a grinning, matted Jason Skoyles appeared on the screen, I felt the old sad bitter taste of cokey snot slide from my sinuses into my throat.

Skoyles had come second. Between you and me I had experienced most of the race as a close to intolerable commotion of color and sound. At times I wondered, not without a lick of envy, if Kim’s sports-drilled brain was able to perceive pattern and advantage where all I could see was thirty-two cars pounding one another to scrap. Only toward the end did something distinct seem to happen. Skoyles had swerved right, unexpectedly, clipping Webster’s back end and sending him slamming into the inside wall just as Tinniswood was attempting a pass. Whereupon Andy Craske had whipped past on the outside and taken the race, followed, a little more than three seconds later, by our boy Skoyles. Thankfully the look of commiseration I’d offered the room seemed to go unnoticed by the others, who, quicker on the league-table arithmetic, had twigged what I hadn’t: that two points for second place had won Skoyles the championship. Tinniswood was uninjured, but unconfirmed reports suggested Skoyles’s shunt had forced Webster’s driver’s-side front wheel into the footwell and shattered his kneecap. Which would put him out of the final two world-championship races. How did Skoyles feel about jeopardizing Britain’s international chances? He stepped up to the interviewer’s microphone.

“Isn’t he handsome?” said Sasha.

“He’s a bit boyish for me,” said Jill. “Girlish.”

“Rubbish, Jill,” I said. My top lip had gone numb. “He’s incredibly handsome. Anyway shh.”

“Obviously gutted but even if he doesn’t compete Willie can still win. Matsuyama’s a good driver but you’ve got to fancy Tullio Ganassi to beat him at Saarbrücken. At the end of the day, injuries are all part of the game. It’s the results that matter, I got one tonight, and hopefully both Willie and I will be representing our country next year.”

My memory of the rest of the evening is both crowded and unclear. I remember, during an upbeat but I think inconclusive conversation with Kim about capitalizing on Skoyles’s success, feeling a sudden heart-leap of shared history, and pressing a big wet kiss into his cheek. I remember a generalized and inane feeling of extreme happiness to be back with all my old friends. Then, as the coke began to wear off, I remember an urgent wish for someone to do something, say something, take off their clothes or tell a good joke, pledge their intense friendship, an itch for stimulation no one could relieve, least of all me, especially when I began to pour red wine into the gap coke had broached between expectation and reality. I remember not being entirely in control of my smile, and having white stuff, halfway between craft glue and feta cheese, in the corners of my mouth. I remember sitting Sasha on my knee, and later telling Jill in the corridor that it didn’t mean anything, we were friends. And then, embarrassed, indignant, succorless, seeking out Sasha again. I remember Lewis telling me more than once to be careful. And at the end of the evening, or rather, when Jill wanted to go home, I remember this fuss, this herd hysteria, this frenziedly embraced idea that I was too drunk to drive.

“Bollocks.”

“It’s not bollocks, Neil.” This was Kim. “You’re shit-faced.”

“I’m a good driver.”

“I’ll order an Uber.” This was Sasha.

Then Kim again: “You can leave the Beemer here overnight.”

“I’m safer drunk than she is sober.”

“Neil, you are not driving my car in that state.”

Now, most of the time, swaying on the way out of a party, you get the sense: It’s okay. Whatever I’ve done, whatever anyone’s said, I’ve gotten away with it. Allowances have been made. And then, just occasionally, something will happen, and you’ll think: Ah. This will have consequences. When I wake up tomorrow this will still be a problem.

Lewis: “Your car, Jill? I thought it was Neil’s.”

At least Sasha didn’t hear it. Or I hope she didn’t.

“Yeah, he is quite proprietorial about it, isn’t he? No, it’s mine. I don’t think Neil’s ever owned a car, have you, darling?”

I can’t remember what I said in the cab home to make Jill cry.

Seven-thirty-nine and there she is.

Far right in the frame, the car a dollying camera. Not in black, but dark red, a long sweeping velvet coat like a curtain, gathered about the mouth, nose poised to part the soft material. Her cheeks, untanned by the streetlight, teased by sharp licks of her hair, black-scratched silver. She looks left, right, hasn’t seen me yet. Approaching Sasha by stealth like this it strikes me that the guilt in the pleasure of seeing a beautiful woman comes from the sense of getting one over — of seeing what they’ll never see. It’s a problem, if you want to love them.

A space: I’ll take it. The trick with parking is to look both ways. Say you’re backing into a space on your left, you naturally look over your left shoulder, così. Hand in the small of the passenger-seat’s back like you’re chaperoning a lover. But then straightaway you should look over your right, like this, and when your rear corner on the driver’s side is aligned with the front driver’s-side corner of the car behind, see, you start straightening up. So you’re using an imaginary line between the midpoints of your boot and his bonnet as a pivotal axis. Slots it in every time. You’d be surprised how much girls like it. I mean not to be crass but it’s got to spark certain associations, hasn’t it? Of aggression held within deftness and control.

There’s a rap on the passenger window.

I unchunk the locks. I find my smile is playing up again. (I must get it fixed.) Sasha gets in, kisses my cheek. Quite near my ear.

Well, it’s only hello.

“Guduguh. Cold. Why did you park?”

“It’s a busy road.”

“But you only had to stop and let me in.”

“Okay. Does it matter?”

I think: our first row. Promising?

“Sorry I’m late.”

“That’s okay. Where’s Jill?”

“Sends her apologies. Hungover, wrapped up on the sofa.”

I double back around the one-way system and swing a left onto Worple Road. Neither of us seems to have anything to say for the moment, so I drive on in silence, my index fingers hooked on the wheel in the unrecommended but insouciant position of twenty-five to five. We’re on our way to Revvin’ Racers, a motorsports-themed restaurant near the junction of the M3 and the M25. Kim’s been in Reading this afternoon, talking to some South Korean die-cast guys about manufacturing another 50,000 Mondeos now that Skoyles is a silver-roofed celebrity, and will meet us at the restaurant. He’s booked us a table partly to celebrate and partly because he wants the four-strong Revvin’ Racers chain (M1, M3, M5, M6) to flog our Mondeos. At Raynes Park station I kink left onto Coombe Lane heading for Kingston Bridge. From there it’s a short run through Bushy Park to join the river again at Hampton Court, then up past the reservoirs to Sunbury and the M3.

I begin to relax into the drive, absolved from unease by the emptyish roads, the purr of the tarmac, the seashell hiss past parked cars. I feel for the blower and twist it red. Sasha says Mmm and rubs her hands in the noisy warmth. I look across. In the gloom of the car, her black hair and brown skin, her red coat and lips, are all one shade, a sharp dark profile cut against the light outside.

“How’re you feeling today?” I say.

“Fine. I didn’t drink much. And we hardly overdid it on the charlie. How are you feeling?”

“Bit green around the gills. Toujours vivant.”

“You were very drunk.”

“Was I?”

“Very.”

“I’m sorry. I think the relief must have lowered my tolerance.”

“Relief? Oh, the race. Yes, you must be pleased.”

“Have you taken a look at Twitter today? The pic of Skoyles looking angelic with the trophy. Twelve thousand retweets by ten this morning. Closely followed by that clip of the crash. Our public can’t decide if he’s a hero or a villain. So they’re going with both. Either way, Kim reckons we’ll be sold out by Christmas. We got an order this morning from Japan for twelve hundred.”

“He told me.”

As we take the bend by the Kempton Park grandstand the motorway veers into view ahead of us, curved like a cello’s hip over the Sunbury Cross roundabout. I change down to third and, glancing right, roll onto the roundabout ahead of a Porsche indicating right for a later exit. His lights search my rearview, and the thrill of a graceful pass — of working with another good driver — sends me gunning up the ramp to the overpass with an extra push of speed. I think: driving now.

Like an instructor prompting an emergency stop, Sasha slaps the dash. “I forgot to tell you. I spoke to Luke today. He and Helen are giving it another go.”

“You’re kidding.”

“No. She’s moving back this weekend. She’d been sleeping with some cardiologist, apparently. And the other morning she woke up in his bed, saw him in the en suite washing his hands, and it was exactly like coming round from anesthesia, she said. Rang Luke from the car to work and begged his forgiveness.”

“Good news, I suppose.”

“I think it is. Maybe she’s not such a bitch after all.”

“I’ll reserve judgment on that.”

“You know you told me that you loved me last night?”

A rich bulge of fear and joy pops and spreads in my belly. Did I tell her? I don’t remember. But that doesn’t matter — I’ve been telling her for seven years.

“I did? When?”

“When I was sitting on your knee. Several times, in fact. You squeezed me really tight and said, ‘I love you, I love you, I love you.’ ”

“Well, I do, a bit.”

I feel, flying over the Shepperton reservoirs, the still black water lit silver like Sasha’s hair, the overpass incorporating car into sky, the same delightful shock of nothing-under-you, the same heart-squeezing happiness as replaces mortal fear in planes, when the alarm (the relief) goes ding and the reaching up is over. Sasha sighs.

“Our kiss.”

“Yes.”

“I liked it.”

“So did I.”

“But I wish we hadn’t.”

“Why? Because of Kim?”

“Partly, yes. And partly because if I kiss you it makes everything pointless. Don’t you think? It makes me feel dizzy, it’s so loose, so wasteful.”

I smile to myself. We’re gaining on another BMW, a newer, faster 5 Series, dawdling at seventy ahead, doggedly denying the social Darwinism of the fast lane. I flash him three times, and when he fails to budge, I check the mirror, change down to fourth, and yank past him in the middle lane. I slap the indicators on, begin my drift back into the fast lane, and, touching her lightly on the thigh, turn to Sasha.

“Let’s just enjoy ourselves tonight, okay?”

“Neil.”

“What?”

There’s a flash and the scream of a horn but it’s too late.

I think about crashes all the time. Any good driver does. Because to be good is to be safe, right? To be good is to be smooth. And so naturally, with every near miss, with every eluded other future, I think about the serrated crunch, the jolt that would have consummated the frictionlessness.

And how it didn’t happen.

Of course I’ve had my fair share of scrapes: the bumps, the prangs, the kiddie crashes. At college I backed Kim’s Peugeot 307 into a bollard and cracked a taillight. But I’d never had a crash before.

I cannot believe it.

Listen, if it rankled, me flashing and passing on the inside, I can’t say I blame you. If I’d been you . . . well, it would have pissed me off. But it’s the road, you know. It’s the motorway. There’s no room for error. You have to stay calm.

But you didn’t, did you?

You wanker.

Your temper got the better of you.

Your name is Richard Ellacott. You’re forty-one. You’re married with an eleven-year-old son. You were recently promoted to the board of a civil-engineering firm based in Maidenhead. The new BMW was part of the package. They found a bunch of flowers on the back seat, under your suitcase. For your wife, or your girlfriend. We’re coming to see you, once we’ve picked up the Beemer (Jill’s Beemer). Which you may not like, but tough. We’re coming. After all, we were close, once. And it’s not as if you’ll know we’re there.

When we collided you had nowhere to go but right. I steered left, back into the middle lane, into the path of an oncoming Astra, which, thank Christ, braked in time. Sasha suffered mild whiplash, which may affect her cello-playing for a few weeks, but on the whole we’re fine. You hit the railings of the central reservation and your off-side front tire blew out. You lost control. You swerved back into the fast lane, then, taking a violent right, smashed through the central reservation, missed an onrushing truck by a matter of feet, and struck the concrete stanchion of a gantry sign (M25 Heathrow) so hard the front end of your Beemer was “obliterated,” according to the police report. On impact your head hit the windscreen and your knees crumpled into the steering column. Later, in hospital, you were diagnosed with, among other less serious things, the fracture of both knees and stress possible mild traumatic brain injury.

Which may mean: You’ll suffer some short-term memory loss, and/or difficulty with decision-making. The exogenous depression you may suffer may or may not be distinguishable from the endogenous depression you suffered, or didn’t suffer, as a result of the affair you were or weren’t having, before the crash. Stress may. The doctor also says you may well make a full recovery.

But what about me?

It’s not like I haven’t suffered a shock. You know, there’s plenty to be glad about. I’m glad the crash wasn’t worse, I’m glad I’m okay. I’m glad Sasha’s okay. I’m glad you may be, too. I’m glad that the Beemer’s held up (new door, new front fender) and that my bonus from Kim covers the excess and loss of the no-claims. I’m glad neither the police nor the insurance wants to bring suit, and that Martin, Kim’s lawyer, thinks that when you wake up, we’ll come to the same conclusion — that neither of us was looking ahead.

I’m glad Sasha’s forgiven me (“It was nobody’s fault. You arsehole”). In a way, we’ve never had a more perfect opportunity. What better cover than post-traumatic solemnity? We need to talk it through. It’s best if I go alone. Innocence rarely so feignable. If I want to leave it for a while, it’s only because, for the moment, I can’t think ahead — it’s like the seconds after the first impact, not knowing, no control, the stillness of free fall. And then, sooner or later, things will come to rest. Things will settle. And we’ll start again.

But the fact is, I crashed.

How can I admit it to Jill? That I made a mistake? How can I admit it to myself? I’m a good driver. But how can I drive her anywhere now? It’s like having an affair, holding back on an admission I’m not sure my dignity, or the relationship, could survive.

Jill and I sit for a while in the pastel waiting room of Barry’s Garage, flicking through magazines (she Elle, me Car). Then Barry takes us through to the oil-stink and clank out back, where, with a postoperative groan, the Beemer is being lowered on hydraulic crutches. Hands plunged in blackened pockets, Barry gives us a wordless tour of the bodywork, pointing with his toe. It’s a good job. You can’t see the join. I pay Barry in cash and he hands me the keys.

Without thinking I toss my jacket in the back and lean to lower myself into the driver’s seat. Jill clears her throat.

“It’s okay, Neil,” she says. Her face is darkly doubled in the gleam of the roof. She holds out her hand for the keys. “I’ll drive.”