One sunny winter afternoon in western Michigan, I took a ride with Leon Slater, a slight sixty-four-year-old man with a neatly trimmed white beard and intense eyes behind his spectacles. He wore a faded blue baseball cap, so formed to his head that it seemed he slept with it on. Brickyard Road, the street in front of Slater’s home, was a mess of soupy dirt and water-filled craters. The muffler of his mud-splattered maroon pickup was loose, and exhaust fumes choked the cab. He gripped the wheel with hands leathery not from age but from decades moving earth with big machines for a living. What followed was a tooth-jarring tour of Muskegon County’s rural roads, which looked as though they’d been carpet-bombed.

Slater’s 1997 pickup has 200,000 miles on it and countless scars from the obstacle course of Brickyard Road. “My wife keeps yelling at me, ‘Buy another truck!’ ” he told me. “I’d hate to drive a new car on this road.”

This story was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, a nonprofit devoted to journalism about inequality.

Speaking over the rattling of the truck, Slater pointed to the spot where an Amish woman had been driving a buggy when her horse stepped into a deep pothole and injured its leg. (Patches, age eleven, had to be put down after the incident, she later told me.) He showed me where he’d watched a school bus tilt sideways as the driver struggled to get out of a massive crater in the middle of the road. After the incident, Slater hauled in fifty cubic yards of clay and sand with a dump truck and filled the pit himself.

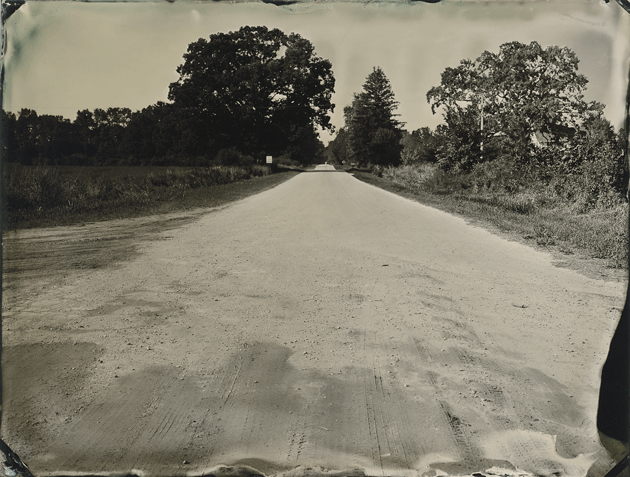

Like thousands of other secondary roads in the country, Brickyard Road is transforming into gravel and dirt.1 Before my visit, Nancy, Leon’s wife, had emailed me pictures of the street. If the photos had been black and white, it would have been easy to imagine they were from a hundred years ago.

Things were even worse back then. In the summer of 1919, the U.S. Army wanted to see if it was possible to move tanks and trucks from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco, a distance of 3,251 miles. More than half the route was dirt track. Slowed by sand and “gumbo mud,” the convoy managed an average speed of 6.07 miles per hour. The journey took two months. A young lieutenant colonel named Dwight D. Eisenhower was on the mission; it made him a lifelong advocate for good roads.

After Eisenhower became president, he signed the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, which established funding for what became known as the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways.2 Thus began decades of work on the 42,000-mile system, which was declared finished only on October 14, 1992, with the completion of a section of I-70 in the Colorado Rockies.

Long before Eisenhower, others had pushed for change. In 1880, when the bicycle was becoming popular, roads were crude and even major routes were often impassable. Cyclists formed the League of American Wheelmen to lobby for improvement but saw little success. In the 1920s and 1930s, the mantra became “Get the farmer out of the mud,” and the advent of the automobile brought rural America to the cause.

The pavement on Brickyard Road. All tintype photographs from Michigan by David Emitt Adams

Brickyard was one of those muddy roads. On a map from 1877, it appears as an anonymous dirt route. It was named after a brickmaking operation on land owned by Slater’s great-great-grandfather, John L. Slater, who emigrated from Prussia. The movement didn’t spread out to Michigan until the 1950s. At that time, a hot liquid form of petroleum called bitumen was sprayed on the surface, and crushed stone was spread to a depth of some three quarters of an inch over the soil, which was then compacted. This process is called chip sealing. Slater, born in 1953, remembers the new paving from when he was a child.

The blacktopping of Brickyard Road was an unremarkable event in the history of the betterment of the 2.6 million miles of road that existed in America when Eisenhower made his journey. Now, though, Brickyard is unremarkable for a different reason — it’s one of countless failed roads, ranking at the bottom of the 10-point Pavement Surface Evaluation and Rating scale used by road engineers.

Some experts have concluded that it’s better to “depave” and let failing asphalt roads return to gravel. With budgets tight, their reasoning goes, this would at least provide motorists with a better driving experience than would a broken-down paved road. Also, a gravel road is cheaper to maintain than a paved road. Studies by more than a dozen different agencies around the nation show the range for gravel maintenance costs: from $2,000 to more than $8,000 per mile annually. And for pavement: from $13,000 to $37,000.

Brickyard is among the roads that the Muskegon County Road Commission has slated to be turned to gravel, twenty-eight miles in all. Brunswick Road, which intersects Brickyard about a half-mile north of the Slaters’ house, was the first to go, in 2008. Residents complained bitterly about health issues and dust after it was ground up, so the county halted the depaving. But there’s no money to refurbish all the damaged roads that are paved in name only.

It would be comforting to think of these roads as aberrations that plague one isolated place in economically depressed Michigan. But they’re not. I’ve been road-tripping around the country, shunning interstates, since the Seventies, and I’ve noticed a sharp decline in the quality of our secondary roads — especially over the past ten years. According to TRIP, a nonprofit transportation-research group, more than half of the nation’s major rural routes are in “fair,” “mediocre,” or “poor” condition. We as a nation are on a journey down regression road. Roads symbolize one of the fundamental contracts between a government and its citizens. They are among the most direct and regular relationships people have with the state. If the roads are failing, it means government is failing.

Ken Skorseth began his road-construction career in South Dakota in the early Seventies, as a private highway contractor. His training embraced a dogma that hadn’t changed in half a century: roads went from dirt or gravel to asphalt. Period. “I got in on the latter part of the interstate highway construction era,” he told me. “County commissioners would tell you they had a goal to make all county roads ‘black.’ In other words, asphalt.”

He became superintendent of the Deuel County Highway Department in 1981. His focus was on maintaining low-volume roads, those (paved or unpaved) with few passenger miles — fewer than 250 vehicles a day. Soon enough, the principles he had learned earlier in his career were turned upside down: flat budgets, rising costs, and heavier farm equipment meant that keeping roads paved was increasingly impossible. Desperate to keep such routes passable, he quickly turned his attention to gravel. It wasn’t as if he had a choice — if he wanted to stay on budget, he needed stone, not asphalt. He left the county and took a job as the manager of a transportation program at South Dakota State University, and his reputation spread. He began getting calls from all over the world. In 2000, he was the lead author of the Federal Highway Administration’s Gravel Roads Maintenance and Design Manual. He became known as the “gravel-roads guru.”

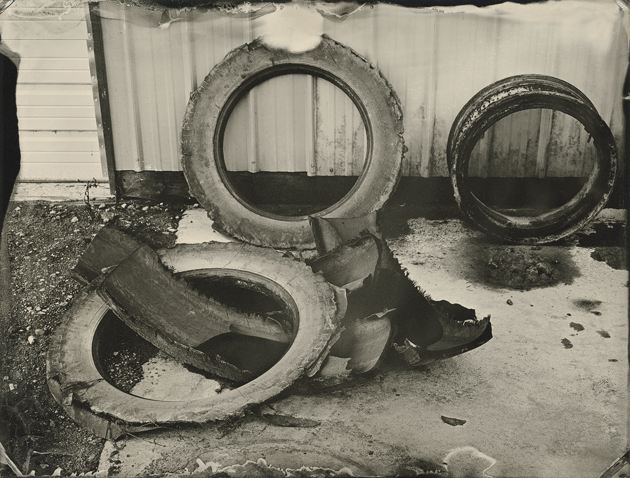

A damaged tire outside Leon Slater’s workshop

Around the country, many roads were paved that should have remained gravel. It was an easy decision in the prosperous post–World War II years, when the petroleum products used in asphalt were cheap and labor costs were relatively low. But by the Nineties, even as the economy boomed on the coasts, the middle of the country was entering a de facto depression. At the same time, the cost of asphalt escalated. Skorseth was the man for the moment. Techniques such as chip sealing, as was done on Brickyard Road, were doomed propositions. There the local soil is clay, which holds water. Without a more substantial foundation, paving over clay will lead to potholes.

“I never dreamed that by the end of my career we would be talking about having to go back to gravel,” Skorseth said. Road engineers and politicians often sought him out for advice, but when he urged depaving roads he encountered “extreme” resistance.

“Early on we were kind of the bad guys,” he said. “We were telling people, ‘Look at the condition of your system, all the roads built in the Sixties and Seventies. How are you going to rehabilitate those with current budgets?’ It’s astounding how much it changed, particularly after 2008.” The recession that began that year has theoretically ended, but many local and state road budgets have not recovered. Suddenly Skorseth went from pariah to visionary.

The trend toward gravel caught the attention of the Transportation Research Board, part of the National Academy of Sciences, which commissioned a report. Converting Paved Roads to Unpaved was released in early 2016; Skorseth was among the authors. The T.R.B. collected data from 139 roads departments (a fraction of the thousands in the country) and found that agencies in twenty-seven states had depaved some roads, most in the past few years. Agencies in other states were in denial, Skorseth said, about the need to move to gravel.

“It was an eye-opener even to me,” Skorseth acknowledged. “Politicians talk about ‘preserving their pavement.’ I laugh at that term. The road is so bad, there’s nothing here to preserve.”

He told me that gravel is often better on a low-volume road because unlike pavement, it can be maintained by one operator with a single machine, a grader with a wide blade that makes it smooth. “I call it upgrading to gravel,” he said, since “many failing pavements are actually more dangerous to drive on than untreated gravel surfaces.”

Eventually, however, if you drive on gravel roads on a daily basis, your windshield breaks, your tires wear out, your front end goes out of whack. A 2013 study by the Lyles School of Civil Engineering at Purdue University said,

The estimated cost for operating a vehicle on a gravel road is 14.33 cents per mile higher than on a paved road. . . . Although this cost is significant, it is borne by vehicle owners and not the agency.

It’s another example of the death of the commonweal in favor of privatization.

I’ve paid for bad roads. When I used to travel to my house in rural northern California, the trip was an expensive ordeal. The county paved some of the gravel road at the base of a nearby mountain in the Nineties. But a few years ago officials reversed course and returned that section to gravel. Oddly, a creek that once was piped beneath the road was left to flow over the top. Last winter, after a storm, that “creek” became a raging river I had to ford, and the car barely made it through. For forty-five miles on the remaining allegedly paved road, I often went no faster than fifteen miles an hour because it was pocked with craters. (Despite crawling along, I hit the mother of all potholes.) It turned out that on the trip, I had cracked a tire rim that cost $108.50; part of the axle system was damaged, too, which set me back $518.40.

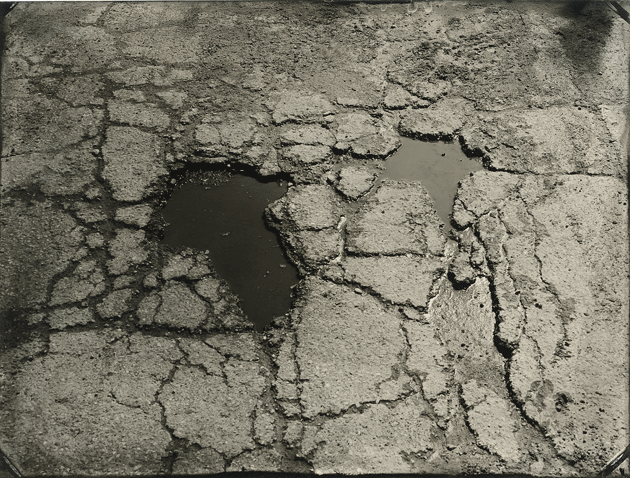

Crumbling asphalt and rain-filled potholes in front of the Slater family’s dairy farm

Each American driver pays about $450 per year toward roads, according to the Journal of Infrastructure Systems. Europeans fork over on average 2 to 3.5 times as much — the difference is largely in fuel taxes. Americans have always resisted giving such financial support for infrastructure projects. In the 1800s, farmers labored for free on road crews in lieu of paying taxes, and in 1913, Missouri governor Elliot Major led 50,000 citizens on a volunteer effort to fix an “ocean of mire” in the state. A gasoline tax was not implemented until the 1920s, and only then did roads begin improving methodically. But, nearly a century later, a gulf has opened up between tax revenue and the cost of materials and labor. The federal gas tax, 18.4 cents per gallon, was last raised in 1993 and has since lost more than one third of its purchasing power. Only three states currently index their gas tax to inflation.

Tire tracks in a pothole filled with sand and clay

Despite the declining condition of our roads, conservatives have long wanted to cut their funding, terming this “devolution.” The American Legislative Exchange Council, a right-wing think tank, offers a ready-made bill called the Devolution of State Highway Systems Study Act, which proposes turning over the maintenance of state roads to local agencies. In 2009, a state representative, Glenn Vaad, put forth such a proposal in the Colorado legislature. The movement reached the federal level in 2013, when a Georgia Republican, Tom Graves, introduced a bill in the House of Representatives that would lower the federal tax to 3.7 cents per gallon and let the states control that diminished revenue.

That bill went nowhere, but our infrastructure continues to crumble. Bridges are part of the equation. While a bad surface can merely damage your car, a failed bridge can be fatal. In 2015, a bridge on I-10 near Palm Springs, California, collapsed. It had been deemed “functionally obsolete” in the 2014 National Bridge Inventory. And ten years ago in Minneapolis, a bridge collapse on I-35 killed thirteen and injured scores. Some 63,000 bridges, about 10 percent of the U.S. total, are “structurally deficient,” according to the American Road and Transportation Builders Association.

Candidate Donald Trump pointed this out in one of the Republican presidential debates in early 2016: “We’ve spent four trillion dollars trying to topple various people,” he said. “If we could’ve spent that four trillion dollars in the United States to fix our roads, our bridges . . . we would’ve been a lot better off.” Yet as president he has been vague about his infrastructure plans. All that can be gleaned from his tweets is that he wants to privatize the main highways. This won’t help secondary roads.

Americans are in an anti-tax mood these days, too. In early 2015, Muskegon County voters, by a 2 to 1 margin, turned down a ballot measure to raise road taxes. It’s hard to blame them. The county, which hugs the shore of Lake Michigan, has lost tens of thousands of well-paid manufacturing jobs in recent decades. That drew me here in 2009 when I interviewed people at the Fifth Reform Church, about a dozen miles from Brickyard Road, where a Feeding America network truck was giving away food to 224 residents, most of whom wore clothes that made them appear to be comfortably middle class. When I interviewed them, however, I found that many were desperate for food.

State law requires that townships must pay about half the cost of road improvements. Melvin Black, a road commissioner in Muskegon County, told me that Holton Township, which contains Brickyard Road, saves about $10,000 a year for its road budget. “They’d need a hundred thousand a year minimum to gradually bring the roads back,” he said.

Black blamed farmers’ heavy equipment for damaging the roads — that means Leon Slater’s relatives, who are dairy farmers. But Slater pointed out that the farms employ some forty people in a place with few jobs. Also, city residents drink the milk that travels every day on local roads in a huge tanker truck. I wondered aloud to Black: Doesn’t the government have some responsibility? Good roads benefit all of society. Local politics, however, will prevent the most immediate fix: an upgrade to gravel. Brunswick Road was pulverized before Black was appointed to the board. “But let me tell you, I was there to catch the heat. I said, ‘I will never vote to grind up a road.’ ”

This idea elicited a sigh from Kenneth Hulka, the managing director of the county road commission. “I’m not sure that’s in the best interests of the motorist, because a well-maintained gravel road is much better than what they’re driving now,” Hulka said.

As for Brickyard Road?

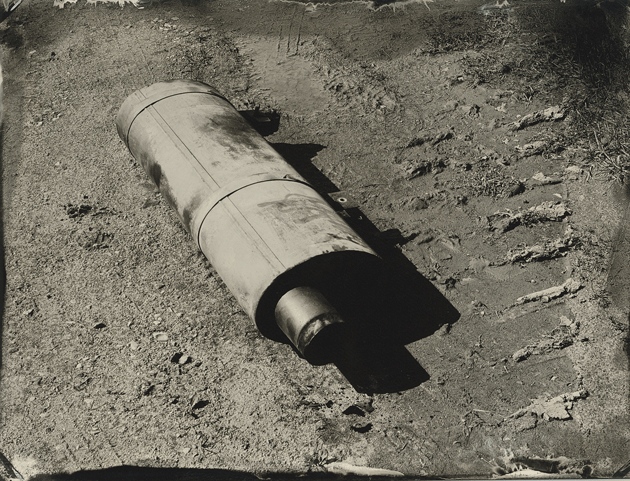

A damaged muffler on Slater’s property

“It’s gone,” he said of its existence as a paved road. “There’s nothing you can do to patch it.” To create a solid base and properly asphalt the one-mile stretch in front of the Slaters’ home would, in Hulka’s estimate, cost $300,000. When Hulka started the job in 2003, asphalt cost between $24 and $27 a ton. “We’re seeing sixty-four dollars and up right now,” he said. “And our revenue is almost the same.”

In late 2015, the Michigan legislature passed a 7.3 cent gas-tax increase, and some of that money has reached Hulka’s department. But the fees don’t fully phase in until 2021. Hulka said recently that the funding helped with the upkeep of the main roads and has thrown a little bit of money at the secondary ones. But he fears that contractors will likely raise prices after years of being starved. And some of the future increase will be lost to inflation. None of the new money will go toward fixing township roads such as Brickyard. It won’t be repaved. Nor will it be ground up. It will continue to decompose, like so many of the nation’s roads.

After Slater and I spent most of an afternoon driving around, we hit an especially bad pothole. The old GMC suddenly erupted in an ear-shattering blast.

“I think I just lost my muffler,” Slater announced. A minute later, the engine sputtered out. He fired it up again. The truck took us a few hundred feet. Then it died for good. I walked the quarter-mile back to his house and got my rental car. He chained the GMC to the rental and I towed him in.

“Every day it’s like this,” Slater said. “You can get really shook up.”