A formative experience of my life occurred the day — I was then twenty years old and a student at the City College of New York — that an English teacher put into my hands D. H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers. I was a working-class kid, there were few female protagonists in the books I read, and until then I’d never heard the term “coming-of-age novel.” But I knew one when I saw one, and Paul Morel’s emotional struggle to leave home put the matter so starkly and so dramatically that, even at that tender age, I felt myself communing with the primitive conflict at the heart of the tale. I read the book in one gulp, came back to class entranced, and from that day forward, Sons and Lovers was biblical text. It was as though I had undergone a conversion experience. From here on in, I knew, literature with a capital L was to be my Book of Wisdom: it was to literature that I would turn to understand what I was living through, and what I was to make of it.

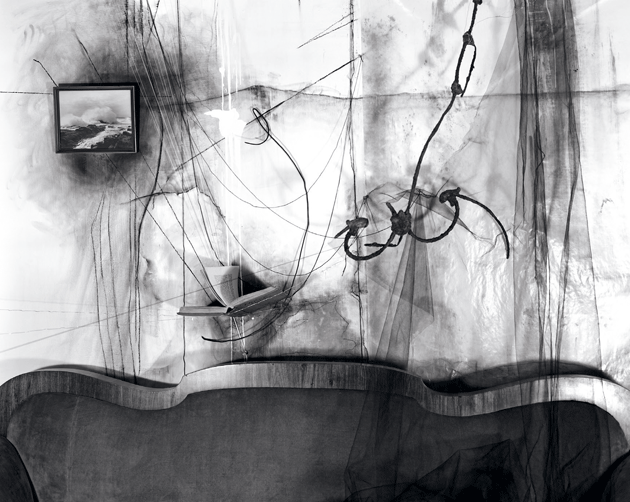

“Three Loves,” by Lauren Semivan. Courtesy the artist and Benrubi Gallery, New York City

I read Sons and Lovers three more times within the next fifteen years, and with each reading, I identified with another of the characters. The first time, it was Miriam, the farmer’s daughter with whom Paul loses his virginity. I got her immediately. She sleeps with him not because she wants to but because she fears losing him. During intercourse, her terror is such that instead of yielding to the experience, she lies beneath Paul and thinks, Does he know it’s me, does he know it’s me? Miriam’s primary need is to know that she is desired, and for herself alone. The dilemma was devastating: I felt the heat, the fear, the anxiety engulfing each of these two, but most especially, I felt it as though I were Miriam herself. I was twenty years old. I needed what she needed.

The next time I read the book, I was Clara, the working-class woman who is sexually passionate, wants to engage with erotic life, but is still alive to the potential for humiliation hidden in her need to feel that it is she who is being desired for herself alone. The third time I read the book, I was in my early thirties — twice married, twice divorced, newly “liberated” — and I identified with Paul. Now preoccupied with desiring rather than being desired, I gloried in giving myself up to the shocking pleasure of sexual experience: rich, full, transporting. At long last, I was the hero of my own life.

Only, of course, I wasn’t.

My point here is that for me, this particular rite of passage — the fraught discovery of the joy, the misery, the awe of making oneself vulnerable to passion — was permanently sealed into the continued rereading of a great novel that repeatedly seemed to mirror my own gathering development, at the same time that its influence as a work of art broadened and deepened, filling me with wonder again and again at the intimate connection between life and literature.

The illusion of self-mastery that comes with ecstatic sex is just that, an illusion. But for however long sex outside of marriage was prohibited by Western civilization, that illusion retained power of an almost mythical order. When I was a girl, in the Fifties, the culture was still joined at the hip to the restraints of bourgeois life, which only fed the dream of transcendence interwoven with the promise of self-discovery wrapped around the astonishment of sexual passion. Except for one vital difference between then and now: then we didn’t call it sex, we called it love; and the whole world believed in love. My mother, a communist and a romantic, said to me, “You’re smart, make something of yourself, but always remember, love is the most important thing in a woman’s life.” Across the street, Grace Levine’s mother, a woman who lit candles on Friday night and was afraid of everything that moved, whispered to her daughter, “Don’t do like I did. Marry a man you love.” Around the corner, Elaine Goldberg’s mother slipped her arms into a Persian lamb coat and shrugged. “It’s just as easy to fall in love with a rich man as a poor man,” she said, but her voice was bitter precisely because she, too, believed in love.

It was a working-class, immigrant neighborhood in the Bronx. Our lives might be small and frightened, but in the ideal life — the educated life, the brave life, the life out in the larger world — we imagined that love would not only be pursued, it would be achieved; and once achieved, it would transform existence; create a rich, deep, textured prose out of the inarticulate reports of inner life we daily passed on to one another. The promise of love alone gave us the courage to dream of leaving those caution-ridden precincts and turn our faces outward toward genuine experience. In fact, it was only if we gave ourselves over to romantic passion — that is, to love — without stint and without contractual assurance, that we would have experience.

We knew this because we had been reading Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary and The Age of Innocence all our lives, as well as the ten thousand middlebrow versions of those books, and the dime-store novels coming just behind them. In literature, good and great writers as well as mediocre popularizers had made readers feel the life within themselves in the presence of words written to celebrate the powers of love.

There might, of course, be a price to pay. One might be risking the shelter of respectability, even in the Fifties, if one fell in love with the wrong person — and don’t forget, Anna and Emma did end up suicides — but no matter. The only truth for us was the depth of emotion these heroic figures generated through their courage to risk all for passion. It’s interesting to realize now that while we thought we were contemplating passion as an instrument of some higher plane of achieved life, we were really seeking it as a goal in itself. No one ever had a word to say about what happened afterward. That’s why, when the movie ended with the lovers riding off into the sunset, we walked out of the theater feeling vindicated.

Each time I read Sons and Lovers, I found that I’d gotten much in the novel wrong. For me, this is a common experience: rereading this or that book that has been important to me throughout the years and repeatedly discovering that a narrative I’d long thought memorized was being called into startling question. I’d gotten this or that character or this or that plot turn wrong, and I could never help marveling: if I got so much wrong, how come the book still has me in its grip?

When I came to read Sons and Lovers recently — in, shall we say, my advanced maturity — it wasn’t so much that I’d gotten many of the details wrong (which I had), but rather that my memory of the oedipal theme of sexual passion as the central experience of life was wrong. That, I now saw, wasn’t really what the book was about, and I found it all the greater and the more moving that I had held it close to my heart all these years for the wrong reasons. The psychological complexity of the novel, which had eluded me, now seemed to have been waiting for me to grow into the understanding it required of its readers.

Set at the turn of the twentieth century in a mining village in the English Midlands, Sons and Lovers tells the story of the Morels and their four children. Gertrude (a bookish woman of romantic sensibility) and Walter (a fun-loving miner) meet at a dance; she is drawn to his good looks, his gaiety, his talent for dancing, while he is attracted by her responsiveness to his sensuality. They develop a passion for each other and they marry. He promises her a house of her own, a good enough income, and tender fidelity. Soon enough, she discovers that on none of these can he deliver:

He had no grit, she said bitterly to herself. What he felt just at the minute, that was all to him. He could not abide by anything. There was nothing at the back of all his show.

For his part, he is startled to find that she cannot bear disappointment well: it turns her bitter and austere. In no time at all, bewildered by the constant sense of accusation he now feels at home, he escapes to the pub every chance he gets.

Eight years down the road, when the book begins, Gertrude Morel is thirty-one years old, pregnant with her third child, living in undreamed-of poverty both material and emotional, and repelled by her husband, whom she and her children now regard as a violent, hard-drinking lout. Yet her romantic sensibility has not deserted her. It is to her sons, then, that she turns for the kind of companionship required to feed a starved inner life. At first she hopes to make a soul mate of William, the eldest. But it is Paul, the second son and our protagonist, who is destined for that role. From the very beginning, Lawrence tells us, Gertrude “felt strangely toward the infant,” noticing the “peculiar knitting of the baby’s brows, and the peculiar heaviness of its eyes, as if it were trying to understand something that was pain.” Her soul’s anxiety has entered into Paul — at the age of three or four, he cries for no reason, grows melancholy for no reason — and from that moment on, we know this is not exactly mother love at work here.

Gertrude sees her spiritual salvation joined to that of her son, who declares as a teenager that he will never desert her. But as Paul grows into young manhood, he comes to realize that he must leave her behind. Where he is going, she cannot follow, and not only because she is his mother. The life she has lived — the thoughts and feelings she has not had — will not permit it.

At the heart of it all, of course, lies erotic love. As Paul’s need for it grows — and the two women, Miriam and Clara, become the instruments of his awakening and initiation — he delves ever deeper into its extraordinary force, until he finds that passion has the ability to mimic liberation but not to actually deliver it. The struggle between Paul and the illusion of liberating sex, I now saw, was the spine of the novel. It was this that I had repeatedly failed to register, along with the complexity of the characters.

In the very first pages of the book, for example, while she is pregnant with Paul, Gertrude laments the “poverty and ugliness and meanness” of her life:

“What have I to do with it?” she said to herself. “What have I to do with all this? Even the child I am going to have! It doesn’t seem as if I were taken into account.”

These words are part of a speech I did not at all recall. I had thought of Gertrude as a rather one-dimensional person: a tight-lipped woman whose obsessive involvement with her own betrayed dreams of life has deprived her of perspective. But here she is sounding more like a woman of 1970 than of 1910, conscious of a self that, in the midst of the endless quotidian, she knows is missing.

Then there is Walter, the husband. I remembered him as a Caliban, but he is little more than a childish man whose gift (his only gift) for innocent sensuality has been steadily eroded by the lack of the very thing that could have made him a better person: sympathetic partnership. In his youth, he had been a great dancer, his love of music embedded in a heart that yearned to be light. And even now, going off to work, he loves his early-morning walk across the fields, often arriving at the pit “with a stalk from the hedge between his teeth, which he chewed all day to keep his mouth moist, down the mine, feeling quite as happy as when he was in the field.” True, he has “whole periods, months, almost years, of friction and nasty temper,” but his spirits invariably recover.

Walter, too, has been left crying in the wilderness. His head is filled with chaos because he is a sentient creature who, unlike his wife, cannot say to himself, “Where am I in all this?” It is precisely his inarticulateness that makes it hard for him to come straight home after work, which leaves his wife doubly trapped in the misery of normalcy outraged:

Mrs. Morel sat alone. On the hob the saucepan steamed; the dinner-plate lay waiting on the table. All the room was full of the sense of waiting, waiting for the man who was sitting in his pit-dirt, dinnerless, some mile away from home, across the darkness, drinking himself drunk.

“They loathed him,” Lawrence later writes. Yes, they loathe him, but they also are him. Paul would rather scrape the skin off his body than admit to any shared characteristic, but — and this I certainly did not remember — he is actually as moody and defensive as his father. At fourteen he is “the sort of boy that becomes a clown and a lout as soon as he is not understood, or feels himself held cheap; and, again, is adorable at the first touch of warmth.” Somewhere within himself, Paul must know that all sensuous feeling in him — tender or murderous, ever ready to burst the skin — comes from his father. But if he allows himself this recognition, it would make him ill. So Lawrence doesn’t make him think about it, but allows the reader to do so.

And then there is William, whom I had completely forgotten, and whose fate is perhaps the most telling of all. William has the soul of an accountant. Absorbed in his white-collar job in London, which he expects will bring him money and a rise in social status, he cheerfully comes home less and less, as children bent on making their way in the city do. But one Christmas, still in his early twenties, he brings home Lily, a secretary to whom he has become engaged. She is beautiful and he is besotted with her even as he seems permanently irritated by her vanity and stupidity — especially now that he sees her through his mother’s eyes. Torn apart by the conflict within himself, repeatedly William quarrels with Lily and instantly regrets his bad behavior. “And in the evening,” we read, “after supper, he stood on the hearth-rug whilst she sat on the sofa, and he seemed to hate her.”

Gertrude goes into shock at what she sees happening to William: that’s how it seems to her, it’s happening to him, as in a Greek tragedy. She herself had been lured into marriage by sexual attraction, but his desperation — the sort that comes with desire being made conscious — no one of her generation has ever seen. She immediately recognizes it as world-shattering.

As does William. His hunger for Lily is hateful to him: it humiliates him and drives him to act in ways that he holds in contempt. He knows that Lily is guilty of nothing more than being herself, yet he cannot refrain from heaping blame on her for his own wretchedness. In a burst of despair he cannot control, he cries out to his horrified mother that should he die, Lily would forget him in a couple of months: that’s how shallow she is.

Just to read the words on the page is to see the torment writ large on William’s face. Passion, passion, passion: hard, mean, wracking, neither sensual nor romantic, only boiling. Passion that is more like war than love: the rawness behind the longing for sexual ecstasy, the depth of its anguish, the fear of ruination, the consequence that can never be undone.

It is a stark and unforgiving look at the price sexual hunger exacted in near-Victorian times. Inescapably, I found myself remembering all those mediocre novels about marriage written during the same era by H. G. Wells, novels in which this same conflict is often at the heart of the narrative. Again and again, there is a working-class boy who longs to rise in the world but is perishing for want of a sexual life, and talks himself into marrying the first girl who seems willing to lie down with him if only he will marry her. Invariably, the protagonist dreads committing himself to such a marriage — he stands on the brink, looking down into a void — but the dread loses out to the killing need. It’s a situation Wells knew intimately. His prose, however, was not up to the task of making us feel his protagonist’s anguish. It is with Lawrence, whose few pages on William and Lily are so penetrating, that the situation comes to life. He makes us shudder on William’s behalf, because what he sees in him, he sees everywhere and in everyone, and that’s how a novelist builds a world.

William dies not long after the benighted Christmas visit, and it will be left to Paul — actually, to Paul and Miriam — to sort it all out. It is through them that Lawrence will investigate exactly how much devotion to either the flesh or the spirit is required to address what I now saw as the underlying concern of Sons and Lovers: how to construct a self from the inside out.

Miriam is nearly sixteen when she and Paul meet. She is brown-eyed, black-curled, beautiful, and inclined toward religion, like millions of women before and after — because it is the only thing available that elevates her above the grubby claustrophobia of an existence whose horizons are right up against her face. Lawrence sees her situation plainly but cannot afford to give her the sympathy allotted to a central character. So he gives her to us like so, one of those women who

treasure religion inside them, breathe it in their nostrils, and see the whole of life in a mist thereof. So to Miriam, Christ and God made one great figure, which she loved tremblingly and passionately when a tremendous sunset burned out the western sky . . . or sat in her bedroom aloft, alone, when it snowed. That was life to her. For the rest, she drudged in the house. . . . She hated her position as swine-girl. She wanted to be considered. She wanted to learn. . . . Her beauty — that of a shy, wild, quiveringly sensitive thing — seemed nothing to her. Even her soul, so strong for rhapsody, was not enough. She must have something to reinforce her pride, because she felt different from other people.

This sense of difference in Miriam is, for Paul, a double-sided coin. On the one hand, he shrinks from the religiosity; on the other, seeing her in church, he often views her as “something more wonderful, less human.”

It is interesting and somewhat painful to see that this inchoateness in Miriam is treated with suspicion, while the same (actually, much worse) inchoateness in her brothers — these wild, hardworking farmhands whom Miriam and her mother are constantly trying to civilize through scripture — is analyzed with equanimity. These boys bitterly resent “this eternal appeal to their deeper feelings.” Beneath their crude scorn, however, is the

yearning for the soul-intimacy to which they could not attain because they were too dumb, and every approach to close connection was blocked by their clumsy contempt of other people. They wanted genuine intimacy, but they could not get even normally near to anyone, because they scorned to take the first steps, they scorned the triviality which forms common human intercourse.

At last, Paul persuades Miriam to lie down with him — possession, he tells her, is a great moment in life, all strong emotions are concentrated there — and of course it is a disaster. They fuck for a week, but after every episode each is left feeling alone and in despair. We don’t know what Miriam is going through, but for Paul “there remained afterwards always the sense of failure and of death. If he were really with her, he had to put aside himself and his desire. If he would have her, he had to put her aside.”

In a sense, Lawrence does for Miriam what Thomas Hardy — with infinitely more sympathy — does for Sue Bridehead in Jude the Obscure: he brings her to complicated life, then sacrifices her to a lover’s demand that makes her the instrument of his need, superficially fulfilled, essentially denied. “You don’t want to love,” Paul raves at Miriam, “your eternal and abnormal craving is to be loved. You absorb, absorb, as if you must fill yourself up with love, because you’ve got a shortage somewhere.” Exactly what Gertrude, for her own reasons, thinks of Miriam: “She’s not like an ordinary woman, who can leave me my share in him. She wants to absorb him. . . . Suck him up.”

Yet our hearts don’t bleed for Miriam as they do for Sue Bridehead, because Lawrence doesn’t love her as Hardy loves Sue. In fact, Lawrence doesn’t love anybody, I finally came to realize, and I recalled that Auden once said of him that he knew everything about the “forces of hatred and aggression,” but of “human affection and human charity, for example, he knew absolutely nothing.”

Here I’d like to digress a bit, with a few words about Sue Bridehead, to make a point about living and rereading. When we first meet Sue, she is bent on becoming a “new woman” of the 1880s. She and Jude — a country cousin come to the big city — meet up, and very quickly she becomes his mentor, showing him how to live freely and honestly, without bending to the shibboleths of religion or social convention. He’s delighted by this and has the inner strength to follow through. Sue, however, turns out to be intellectually brave but emotionally frail and sexually dysfunctional. Over the course of four hundred of the most agonizing pages in English literature, wherein she undergoes some of the worst experiences a woman (now as then) could have, Sue reverts to religious mania, goes half insane, and is convinced that she must pay and pay and pay for having outraged “the gods.”

The first time I encountered Sue, I liked and admired her immensely, but couldn’t fathom the sexual frigidity and was horrified by the manic regression into religiosity. The second time, I was ten years older, had just had an illegal abortion, and, to my own dismay, was experiencing an apprehension I found shocking. Somewhere deep inside, in a place I could not put a name to, I, secular to the bone, was experiencing something like fear of retribution. One day in the street, the words formed themselves in my head, For this you will be punished. I went upstairs, took Jude the Obscure off my bookshelf, and turned to the pages on Sue’s religious mania. It was then that, for the first time, I began to see what a primitive issue abortion is: an act capable of inducing existential dread in the most unlikely of people.

All this I could see and feel through Sue because Hardy’s sympathy for her puts the reader right inside her. Lawrence’s Miriam, on the other hand, never really becomes flesh and blood. Nevertheless, after this last reading, I realized I would never see Miriam the same way again.

In any case, she is soon enough displaced by Clara, a working-class feminist possessed of a haughty reserve that makes her seem mysterious and exciting even though she is a mass of enervating contradiction: hungry for life, fearful and suspicious of all who approach her. Clara falls for Paul, and she sleeps with him. With Clara, he finally knows the rapture of sex; with Clara, he and his partner are drowning together. It is here in bed with Clara that his separation from adolescence — he’s twenty-three! — is completed, and the alarming complexity of life as it is begins to take hold of him.

When at last Paul and Clara lie down together, the love they make is beyond rapturous:

If so great a magnificent power could overwhelm them, identify them altogether with itself, so that they knew they were only grains in the tremendous heave that lifted every grass-blade its little height, and every tree, and living thing, then why fret about themselves? They could let themselves be carried by life, and they felt a sort of peace each in the other. There was a verification which they had had together. Nothing could nullify it, nothing could take it away.

Oh no?

A mere few months and ten pages later:

They did not often reach again the height of that once when the peewits had called. Gradually, some mechanical effort spoilt their loving, or, when they had splendid moments, they had them separately, and not so satisfactorily. So often he seemed merely to be running on alone; often they realized it had been a failure, not what they had wanted. He left her, knowing that evening had only made a little split between them. Their loving grew more mechanical, without the marvelous glamour.

It is passages like these that mark the modernity of the book. The age was pushing all writers to put on the page the entire truth of whatever they found festering in the human psyche: not only sorrow and disorder but sadism, alienation, and the brevity of passion. I now think that Lawrence saw this last by the time Sons and Lovers was published — he was then twenty-seven. But the insight couldn’t stack up against the pressure of that other thing he saw, which was to be his life’s obsession: that to be deprived of experience of the senses, as bourgeois society demanded we be, was truly a sin against life.

Lawrence didn’t know any more on this score than did Hardy, or Wells, or George Meredith: grown-up writers all. What set him apart was simply the astonishing sense of destiny with which he insisted on outing what they all knew but could not directly address. He was like an abolitionist among liberals who say yes, slavery is terrible, but in time, it will die out, be patient — while the abolitionist says fuck that, now or never, and goes to war.

To feel badly but calmly about what is spiritually deforming is the mediocre norm; to rage against it is to become an instrument of revolutionary change. In literature, one does that by naming the crime against nature without pity or caution or euphemism; renouncing in no uncertain terms, as Auden (again) had it, “the laziness or fear which makes people prefer second-hand experience to the shock of looking and listening for themselves.”

The third time I read Sons and Lovers — it was now the early Seventies — I had just left my second husband. All around me, friends, relatives, even neighbors felt free to cry at me, “Why are you doing this? What is it you want?” The answers, even in my own ears, were lame. Why had I left him? After all, I hadn’t married a man I didn’t love, I wasn’t being forced to choose between work and marriage, our sex life was fine. But the times were encouraging me to look with clear eyes at what I was feeling driven to do, and somehow, involving myself once again in the harrowing life of the Morels felt intimately related.

I had married — twice! — because when I was young, a woman alone was a woman stigmatized as unnatural, undesirable, un-everything. Yet each time around, I discovered that I shrank from being seen as one half of a couple: I actually flinched when addressed as “Mrs.” And while I liked my in-laws well enough, I was intensely bored by family life. Worst of all, there were times when, during a cozy evening at home, alone with my husband, I felt buried alive. The heart of the matter was: I didn’t want to be married. I turned the pages of Lawrence’s great novel as though reading braille, hoping to gain for myself the freedom from emotional blindness the book was urging on its readers.

Within seven years following the publication of Sons and Lovers, Lawrence wrote his two acknowledged masterpieces, The Rainbow and Women in Love. He said when he started them that he would no longer write the way he had of the Morels: graphically and with transparency. No, now he would make what he felt dense with meaning; wild and large and mythical. And so he did. Nevertheless, both novels are hard to read these days, so packed are they with a violence of spirit that I find oppressive as well as a shocking amount of the polemic to which Lawrence became ever more addicted. In these books, he certainly got down brilliantly the crime of suppressed feeling: this is where his genius succeeds without parallel. But the part that promises surcease from human anxiety through erotic freedom — there I now feel him wringing his hands, the prose in a fever because he suspects that what he insists is true may not be true.

Lawrence was writing at the beginning of the Freudian century, living in a time that was just on the verge of putting his obsessive concerns at center stage. In fact, his ruling metaphor — liberation through eros — was to become the wedge that modernism used to pry open the uncharted territory of human consciousness. If Lawrence were alive today, this metaphor would be lost to him. By now, we all have experienced the sexual freedom once denied, and have discovered firsthand that the making of a self from the inside out is not to be achieved through the senses alone. Indeed, it would turn out that not only does sexual ecstasy not deliver us to ourselves, but one must have a self already in place to know what to do with it, should it come.