Discussed in this essay:

Women Who Work: Rewriting the Rules for Success, by Ivanka Trump. Portfolio. 256 pages. $26.

No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age, by Jane McAlevey. Oxford University Press. 254 pages. $29.95.

Earlier this year, the New York Times ran a story that read like a parable of twenty-first-century feminism. The subject was Ivanka Trump, and the year was 2013. Ms. Trump had started licensing her name to a line of women’s shoes, jewelry, clothing, and handbags. The label had debuted on the luxury market, but luxury customers were not buying. The future lay in mass retail. Ms. Trump’s image presented a problem: she was “perceived as rich and unrelatable,” an internal document explained. So she gathered her husband and a few employees at her Upper East Side apartment to workshop her brand. At the time, Lean In, by Facebook’s COO Sheryl Sandberg, was number one on the bestseller list, and Ms. Trump wanted a slogan of her own. The brain trust settled on “Women who work.”

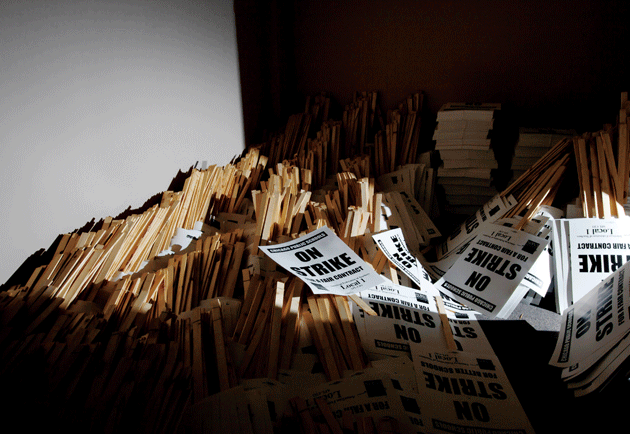

Signs in a storeroom at the headquarters for the Chicago Teachers Union strike in 2012 © AP Photo/Sitthixay Ditthavong

Women Who Work: Rewriting the Rules for Success, published in May, was the capstone of the ensuing brand overhaul. A pseudofeminist business memoir laced with the kind of language that gives away Ms. Trump as a woman for whom work was optional (“You are a woman who works,” she insists nine times), the book captures the worst of “lean-in feminism,” the Sandbergian strain of business-friendly empowerment politics. For the past several years, this ideology has offered middle-class and upper-class women advice on how to navigate a workplace that remains hostile or indifferent to their needs. It prompts women to confront the psychological barriers that hold them back — low self-esteem, fear of failure, lack of will to lead — and offers individual, do-it-yourself solutions. Though not blind to the structural hurdles that keep women from success, lean-in feminism regards them as secondary. What lies within a woman’s control is her decision to embrace power or reject it. If her obligation is toward the former, it is because change, according to Lean In, is top-down. “More female leadership will lead to fairer treatment for all women,” Sandberg wrote in 2013. Hence the theory’s other name: “trickle-down feminism.”

Four years and one traumatic presidential election later, it’s hard not to see Women Who Work as conclusive evidence of the hollowness of this philosophy. Hillary Clinton overcame enough psychological barriers to pursue a second bid for the presidency, but she still hit the “highest, hardest glass ceiling” in American politics. As for the few women who hold power in Trump’s administration, they show little concern for their less fortunate countrywomen. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, a billionaire heiress with a stake in the charter school movement, has announced plans to cut billions of dollars in funding to the country’s public schools, which employ more than 2 million women and serve more than 50 million students. Ms. Trump, who has assumed an advisory role to her father, has advocated staying an Obama-era equal-pay rule that requires large companies to collect data on what they pay employees by gender and race. (As for her treatment of women elsewhere in the world, she continues to outsource the fabrication of her products to Asia, where labor protections are lax.)

Ms. Trump was right to identify working women as a powerful contingent. Her mistake — and it was a mistake: the book flopped — was to address them as a consumer demographic at a time of burgeoning political consciousness. On January 21, three months before the book’s release and just a day after her father’s inauguration, millions of women across the country took to the streets in the first major protest against the new administration. Though not not invited, Ms. Trump was elsewhere. The march was the largest single-day protest in U.S. history, a sign that protesting under the banner of women was a promising strategy.

But the future of this coalition was uncertain even before the event began. The protesters’ demands were urgent — climate justice, racial justice, economic justice, gender justice — but too numerous to take on at once. Many of the marchers were new to activism and would need direction.

Political organizers often say that social movements require institutions to make lasting change. While movements create energy and build momentum, institutions — political parties, nonprofits, or looser coalitions — distill that energy into something concrete and potentially enduring. More important, they grant people a seat at the table where contests for power take place. Institutions recognize institutions more readily than they do individuals. It is easier to lobby for, demand, propose, and enforce political change under the aegis of a nameable group.

Given the female leadership of many of today’s progressive groups and the pull of “woman” as a political identity, one might say that non-elite women are best suited to lead the movement against Trump. Still, the question remains of what institutional form their efforts will take. Some will pursue the electoral route, seeking office and lending support to progressive candidates. Others will mobilize around causes. But there is a third site of resistance, often overlooked by middle- and upper-class feminists, where women are already organizing on a mass scale: the labor movement.

No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age, by Jane McAlevey, argues that all organizers have something to learn from labor. A study of successful strike campaigns since 2000, the book makes the case that mass participation is the key to winning broad democratic reform. Though not a book about feminism, it has implications for feminists and working women generally.

McAlevey, a longtime environmental activist, union-contract negotiator, and a former national deputy director for the S.E.I.U.’s health care division, understands why unions may not be the preferred model for left-wing organizing today. Not all unions are progressive — many are oligarchic and right-leaning; 43 percent of union households voted for Trump — and membership has been in decline since the 1970s. Decades of union-busting and corporate-funded messaging, including recent right-to-work campaigns, have made many Americans suspicious of organized labor. The press has done little to correct the record. (For all the sections devoted to business in American newspapers, there are few devoted to labor.) Meanwhile, in the academy, McAlevey writes, there is an “informal gestalt” that unions “are not social movements at all.”

What unions call to mind in the neoliberal imagination, however — corruption, bureaucracy, narrow interests, white-male dominance — is not representative of what the labor movement is or can be. Particularly in the public sector and in the fast-growing service economy, the face of labor is the face of a woman, usually a woman of color. At their best, McAlevey argues, today’s unions are social movements, democratically run grassroots struggles that reach beyond the workplace and address intersecting needs.

It sometimes seems there is a forged, collective resistance to seeing the best of labor organizing today as being every bit as moral, legitimate, and strength producing as the sixty-year-old civil rights movement.

The civil rights movement itself learned from labor. Some of its most successful tactics — sit-ins, boycotts, and pickets — were aimed at inflicting economic damage, a classic union approach. To assume that workplace struggles are simply about wages is a mistake.

McAlevey offers the 2012 strike by the Chicago Teachers Union (C.T.U.) as an example of what social movement unionism can accomplish. In 1995, a fiscal crisis gave the Illinois state legislature license to “fix” Chicago Public Schools. The legislature authorized C.P.S. to subcontract certain functions, such as janitorial and cafeteria services, to private companies. Teachers were stripped of their right to collectively bargain over working conditions (schedules, class size, the length of the workday), and, for the first time in the city’s history, strikes were made illegal. C.P.S. was reorganized as a business: the Board of Education became the Reform Board of Trustees, and the superintendent, a CEO.

The C.T.U. had once been a militant union. From 1969 to 1987, the teachers went on strike nine times, with one lasting a marathon twenty-five days. (Strikes are a measure of a union’s strength because they cannot proceed without the support of a majority of members.) In the mid-1990s, McAlevey writes, a loose alignment of union leaders across the country that she calls New Labor abandoned this tactic in hopes of encouraging employer compliance; if employers didn’t oppose the union, New Labor leaders promised, the workers would not strike. In McAlevey’s account, this allowed for union growth, but not much else. Labor leaders increasingly turned to business unionism, which made organizers, not workers, the key actors in the bargaining process. Rank-and-file participation fell off, and organizers came to neglect the majority-building tactics that had once made unions powerful.

Tom Reece, the president of the C.T.U. in the mid-Nineties, was a leader in the New Labor style. McAlevey describes him as “strike and conflict averse.” In exchange for contracts with reasonable raises for teachers, he allowed Paul Vallas, the first CEO of C.P.S., to assume “monarchical powers” over Chicago’s school system. Vallas could disband local school councils, replace principals, and fire teachers en masse in schools deemed to be “failing” (as measured by students’ performance on standardized tests). By 1996, when that designation had been replaced by “educational crisis schools,” and then by “on probation,” Vallas was legally allowed to dismiss such a school’s entire staff. That same year, he put 109 schools, many in poor or majority-black neighborhoods, on probation.

Throughout the early 2000s, as No Child Left Behind made standardized testing the norm across the United States, Chicago teachers rallied within the C.T.U. for new leadership. At the same time, community organizers, who were fighting school closures, began to link the closures to a broader pattern of gentrification. When more than a dozen schools were shuttered in the 2005–06 school year, a handful of teachers formed a citywide study group to better understand what was happening to their school system. Their first collective read, Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine, described how big business used natural and economic disasters as opportunities to replace public services with private ones, including schools. “Before Hurricane Katrina,” Klein wrote, the New Orleans school board “had run 123 public schools”; by 2007, “it ran just four.” Meanwhile the number of charter schools increased fourfold. The teachers saw that the Illinois budget crisis of 1995 was for C.P.S. what Katrina had been for New Orleans: a pretext to get rid of public schools entirely.

Unions are “structure-based” organizations, McAlevey writes: members are united not by affinity or self-selection but by the institution that employs them. Many union members do not consider themselves activists, and their networks — book clubs, sports teams, church groups — are not populated by activists either. This, McAlevey argues, is a good thing. Engaging “ordinary people” in the struggle for equality and political power is “the point of organizing,” otherwise activists merely organize themselves. While one cannot build a mass movement of activists alone, activists — like the Chicago teachers who formed that study group — can play a critical role in getting structure-based efforts off the ground.

Out of that group grew two key organizations: CORE, the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators inside the union, and GEM, the Grassroots Education Movement. In 2009, CORE and GEM organized a community forum on the school closures that, despite a blizzard, attracted more than five hundred people. C.P.S. leaders took note, pruning their list of proposed closures for the coming year. “Expectations were suddenly raised,” McAlevey writes. “Teacher-and-community coalitions could beat city hall.”

By 2010, CORE had the “most extensive grassroots operation” of any caucus inside the union, and decided to run its own slate of candidates in the upcoming C.T.U. elections. At the top of CORE’s ticket was Karen Lewis, a National Board–certified teacher who’d taught high school chemistry for twenty-two years. Lewis and her husband both worked in Chicago public schools, as had both of her parents. She was, McAlevey notes, “the only black woman in her 1974 graduating class at Dartmouth.” When CORE’s ticket won, Lewis made their position clear. “Corporate America sees K-through-twelve public education as three hundred and eighty billion dollars that, up until the last ten or fifteen years, they didn’t have a sizable piece of,” she said in her acceptance speech. “This so-called reform is not an education plan. It’s a business plan.”

Under CORE’s leadership, the C.T.U. poured its energy into organizing its own ranks. The C.T.U. is a huge union, representing more than 26,000 teachers, but participation had slumped since the Eighties. Organizers went from school to school to talk with teachers, explaining that their next contract negotiations would not be about winning a percentage-point raise but about securing the future of the schools.

In the fall of 2010, Rahm Emanuel announced his plans to leave the White House and run for mayor of Chicago. The teachers braced for a fight. Emanuel had been a proponent of charter schools and saw unions as an obstacle to their success. With the support of Stand for Children, an anti-union advocacy group, he ran a TV ad chiding the teachers for not working enough. If elected, he promised, he would extend the school day.

Emanuel was elected in February 2011. One of his first acts was to appoint a new CEO and school board, who announced that they would repeal a scheduled 4 percent raise in the teachers’ contract. This breach of faith only galvanized the union. When Emanuel summoned Lewis to his office to discuss the length of the school day that September, he reportedly began the meeting by asking, “Well, what the fuck do you want?” Lewis fired back: “More than you’ve fucking got.” The exchange won the attention of the press. “Karen was black, smart, and bold,” one community organizer told McAlevey, “and that alone made her newspaper-worthy in a city not known for straight talkers.”

Anticipating difficult contract negotiations in 2012, the C.T.U. ran what is called a structure test: a low-stakes action that doubles as a measure of internal strength. The C.T.U.’s structure test was a mock strike vote. To prepare, a forty-person team charted the teachers’ social networks. An essential step in increasing participation would be to identify who within each school was most likely to bring other teachers on board — the people who were what McAlevey calls “organic leaders.” Organic leaders rarely self-identify as leaders, she notes, but can be picked out for their “natural influence with their peers.” They are “the key to scale,” particularly within structure-based organizations.

The results of the mock vote revealed where turnout was low, and where more organic leaders would be needed to pass a real strike vote. A piece of legislation from the previous year stipulated that 75 percent of all teachers would need to participate in a strike vote for it to be valid — “a rather amazing criteria,” McAlevey writes, “given that turnout in typical elections in the United States hovers in the 20 to 30 percent range.”

Teachers, like nurses, are what McAlevey calls “mission-driven workers.” They “labor for something deeply purposeful; they are called to their labor.” Because mission-driven workers understand the direct impact of their absence on the people they serve — people who are not their bosses — the decision to walk off the job can be agonizing. Self-interest is rarely a sufficient motivation to strike. When there is sufficient cause, however, mission-driven workers have all the more incentive to win. In June 2012, the C.T.U. called a real strike vote. Ninety percent of its members — roughly 24,000 teachers — turned out, and against incredible odds, 76 percent voted to authorize a strike.

The strike began on September 10, 2012. On its first day, an estimated 35,000 teachers, parents, and community members marched through downtown Chicago, bringing traffic to a halt. For the next nine days, the teachers picketed their local schools and then gathered downtown to rally. C.P.S. scrambled to keep the schools open, hoping it could stem the tide of calls from parents demanding that they settle. Emanuel’s expensive media campaign to vilify the teachers had failed: parents fed the teachers on the picket lines, and when they couldn’t bring their kids to work, left them under the teachers’ watch. The C.T.U. had put in years of legwork to include parents in the planning process and developed a clear analysis that linked children’s quality of education to teachers’ working conditions; it paid off. In the many interviews McAlevey conducted with teachers for No Shortcuts, one of the most consistent themes was their “disbelief, after twenty-five years of never having been on strike, that their students, and their students’ parents, would fervently lend their support.”

The strike ended on September 18. Emanuel got his extended school day, but the C.T.U. won a pay increase, defended tenure, and managed to keep its long-standing raise structure based on years of service and educational skills. More impressively, the teachers had reformed a huge, concession-prone, in-name-only union into a democratic, majority-run political force at a time when most people thought unions were dead. They had identified and trained a new generation of leaders, from Karen Lewis on down to the organic leaders of the rank and file, who would keep the C.T.U.’s power alive. And through years of meetings, discussion groups, and forums, they had given a political education to thousands of Chicago teachers, parents, and community members who would follow them into the voting booth.

The story, of course, does not end there. In 2013, Emanuel announced his plan to close forty-seven schools, the largest such closure in U.S. history outside of post-Katrina New Orleans. Lewis considered a run for mayor, but was diagnosed with advanced brain cancer. (She is, however, still serving as the president of the C.T.U.) The issues that brought the teachers and the community together — racism, gentrification, school closures, and charter school expansion — were not solved overnight, but the strike had clarified what future campaigns would need to do to win, and how political resistance could be staged through workplace battles.

It is not incidental that McAlevey’s examples of mission-driven workers do what feminists refer to as “socially reproductive” work: the historically feminine labor of reproducing the labor force through care work. Nor is it incidental that many of the things that feminists want — good jobs, fair wages, paid sick and family leave, health care, and child care — are currently under employers’ control. For the time being, feminist struggles are labor struggles, and labor struggles are feminist struggles. The Trump Administration’s push to eliminate public services, from Medicaid to schools, is a battle in which women have a special stake, and not only because millions of health-care workers and educators are women. Years of austerity politics in Europe have shown that when the government ceases to pay for public services, women pick up the slack. Grandmothers and neighbors dedicate more time to watching children; daughters and sisters take on nursing, teaching, and elder care. It goes without saying that most of this work is unpaid.

Looking ahead, McAlevey writes, “education and health care are the strategic sectors” of the service economy, which means nurses and teachers will play a critical role in labor’s future. Hospitals and schools cannot be shipped offshore, and unlike manufacturing workers, health care and education workers have direct, intimate relationships with the people they serve. This raises the bar for when to call strikes, but it gives these workers a strategic advantage, as the C.T.U.’s strike shows.

Education and health care workers also have the experience and insight that the Trump Administration so dangerously lacks. Teachers are fighting what Lily Eskelsen García, the president of the National Education Association, calls DeVos’s “brand new shiny private school voucher program for schools that are allowed to discriminate and over-promise and under-deliver.” Nurse-led canvassing helped kill the disastrous G.O.P. health care bills. Some nurses’ unions, such as the New York State Nurses Association and the California Nurses Association, are leading the push for single-payer health care in their states.

Today, few political organizations on the left, unions included, practice the sort of organizing McAlevey believes builds the mass involvement necessary to beat global corporate leviathans. Instead, “mobilizing” has become the norm, with “authentic messengers” from the grassroots lending a public face to efforts run by a handful of paid staff. The Democrats’ electoral failures have shown that money and top-down messaging are not enough to win; the right will always outspend and outspin the left. As McAlevey writes,

No number of pollster-perfected frames will undo the 100 years of social conditioning that have taught Americans to accept their economic and political roles, and to think “collectivism bad” and “individualism good.”

The way to change minds is to engage ordinary people in a struggle that they must shape and lead themselves. “People participate to the degree they understand,” she observes, “but they also understand to the degree they participate.” Rather than looking upward for support — toward the beneficent feminists of the corporate class — working women should just look around.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly spelled the name of Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel.