The stench first hit me on US 80, just past the catfish feed mill and the processing plant next door. It was late March in Uniontown, Alabama, a whistle-stop thirty miles west of Selma, but even on that mild day last year the odor was inescapable. What began as the smell of manure ripened into the fetor of something dead and mildewed as I drove through the heart of town — an eerily quiet strip of brick storefronts, many of them abandoned. In Uniontown, I would come to learn, the smell functioned the way the weather does in most places. Its vicissitudes were a regular topic of idle conversation, and the local citizenry studied its moods.

The precise source of the smell isn’t clear, but some Uniontown residents point to Arrowhead Landfill, which occupies about a thousand acres of woodland just southeast of town. For eighteen months starting in July 2009, railcars rumbled into the landfill on a daily basis, carting more than 4 million tons of coal ash — a byproduct of coal burning that contains arsenic, lead, and other heavy metals — from eastern Tennessee, some 300 miles away. (A disaster at a power plant there had spilled the ash into a nearby watershed.) Although regulators and the landfill’s owners assured them otherwise, Uniontown residents grew alarmed at the prospect of fugitive ash choking their air and chemicals leaching into their creeks.

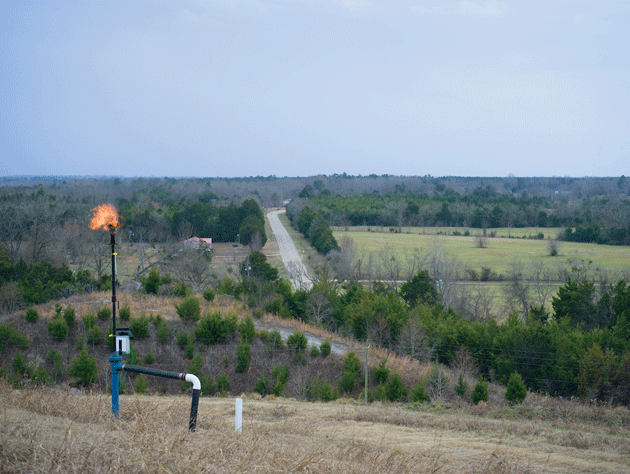

A gas flare at Arrowhead Landfill. All photographs from Uniontown, Alabama, by RaMell Ross

Some also detected a racial dynamic at play. The power plant was in Roane County, Tennessee, which is more than ninety percent white. The same percentage of Uniontown’s 2,400 residents is black. And it didn’t help that despite all the empty acreage available within the site, Arrowhead’s operators chose to truck the coal ash two miles from the rail depot and deposit it on the southern edge of the landfill. Trailer homes line the two country roads that cradle the disposal site. Their occupants for the most part are black.

For Esther Calhoun, who has lived in Uniontown for most of her life, the decision had personal consequences. Her family — black sharecroppers — had lived in the area around the landfill when she was a child, and she still had friends there. From the moment the coal ash began arriving, they complained of noxious fumes and trouble breathing. They stopped spending time outdoors. Rats invaded the trailer of an elderly woman. “They could have started piling garbage and coal ash anywhere on the landfill site, but they chose the closest place to people’s homes,” Calhoun said.

Esther Calhoun, the president of Black Belt Citizens Fighting for Health and Justice

She had been watching Uniontown putrefy for two decades. An attempted upgrade to the overwhelmed sewage system had left human waste and industrial effluent slopping into creeks and pooling in brown, fetid ponds on the grazing pastures she had known as a child. The cheese plant got a permit to dispose of its whey by dispersing it onto unused farmland just a short distance from the high school. The town smelled “hoggish,” and Calhoun had an idea why “everything that’s no good comes down here”: because “we’re black, and we’re poor, and we’re not educated.”

In 2010, Calhoun decided to take action. That year, she joined Black Belt Citizens Fighting for Health and Justice, a community group composed chiefly of local retirees. Its primary mission was to oppose the storage of coal ash at Arrowhead, which was bought out of bankruptcy that same year by Green Group Holdings, a national waste-management company. For years, Black Belt Citizens engaged in a fierce but civil dispute with Green Group. Eventually, however, the company’s patience with its activist rivals grew thin. In April 2016, it filed a $30 million defamation lawsuit against Calhoun and three others affiliated with Black Belt Citizens in federal court in Mobile.

The story of Green Group and Black Belt Citizens is growing ever more common as social media transforms traditional forums of speech. The internet has made it possible for activists to reach a mass audience — even a global one — at zero cost. At the same time, their targets have turned to the courts to impose a cost on that activism. It’s not cheap, after all, to defend even a frivolous lawsuit.

Houses near Arrowhead Landfill

But there is a second element to the story, a more unsettling and pernicious one — a shift in how speech values are prioritized in the United States. The Supreme Court’s First Amendment docket, once dominated by cases litigating the speech rights of individuals — flag burners and pamphleteers — is now rife with cases concerned with the speech rights of corporations, cases that put corporate entities on par with, and often elevate them above, their human counterparts. Meanwhile, the country has witnessed a broader retreat from the long-standing aversion to restricting free expression, both on campuses and in statehouses where legislators have worked to criminalize anti-corporate speech. As the norms that once checked litigious companies erode, activist groups like Black Belt Citizens are at increasing risk of being snuffed out.

In the late Seventies, an Environmental Defense Fund attorney named Rock Pring began to notice something unusual. With alarming frequency, corporate polluters were suing environmentalists who had spoken out or filed lawsuits against them. A few years later, Pring, by then a law professor at the University of Denver, set out with a sociologist colleague named Penelope Canan to study the phenomenon. In a 1988 paper, they came up with a name for these cases: “strategic lawsuits against public participation.” SLAPPs target people or organizations that have spoken out on matters of public concern. Their operational logic is grounded in resource asymmetry — wealthy, often corporate plaintiffs pursuing defendants of modest means, frequently activists. Instead of engaging with their less moneyed critics, the plaintiffs resort to the legal system to intimidate and silence them.

Because they target speech, SLAPPs often take the form of defamation lawsuits. The modern tort of defamation — false speech that harms another person’s reputation — has its roots in historical efforts by the powerful to insulate themselves from the destabilizing influence of bad PR. In 1275, a formative British defamation statute forbade anyone to “be so hardy to tell or publish any false news or tales whereby discord or occasion of discord or slander may grow between the king and his people, or the great men of the realm.” No fake news, in other words, that hurts the king’s ratings.

Downtown Uniontown

In the United States, the First Amendment stripped the tort of this dissent-crushing rationale. To prevent the powerful from stifling public debate, the Supreme Court has over the years placed significant hurdles in the way of government officials and public figures who hope to win defamation suits. For example, it’s not enough to show that a statement is untrue. A public figure has to prove that the defendant made the statement with “actual malice” — that the defendant lied or had a very good reason to doubt the statement’s truth. Government officials and public figures, the reasoning goes, neither need nor deserve the same legal protections as private citizens.

But that conception of the First Amendment is of recent vintage. Despite its apparent absolutism — “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech” — the First Amendment’s speech clause was little more than a bookend to the Bill of Rights until the twentieth century. Judges and legal scholars began to hazard that the amendment might actually mean something only after witnessing the imprisonment of antiwar dissenters and the censorship of media channels by the government’s propaganda machine during World War I.

In 1964, the expanding speech protections of the First Amendment reached the law of defamation, putting new legal obstacles in the path of anyone who would sue for libel or slander. L. B. Sullivan, a public safety commissioner in Montgomery, Alabama, had filed a lawsuit claiming that an advertisement a group of pastors and civil rights activists had placed in the New York Times was defamatory. The ad denounced police treatment of blacks in Montgomery and solicited money to defend Martin Luther King Jr. against spurious state perjury charges. Although the ad contained factual inaccuracies, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the defendants in New York Times v. Sullivan. “Erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate,” Justice William Brennan wrote. “It must be protected if the freedoms of expression are to have the ‘breathing space’ that they need . . . to survive.”

It didn’t take long for a convenient work-around to emerge. To succeed, SLAPPs don’t need to have much legal merit, and as a rule they don’t. “SLAPPs are losers in the courthouse but winners in the real world,” Pring told me. By capitalizing on the uncertainty and the cost — in time, energy, and money — of the litigation process itself, Pring and Canan observed in their 1996 book SLAPPs: Getting Sued for Speaking Out, the suits “encourage the active to return to the vast ranks of uninvolved and apathetic Americans.”

The wave of SLAPPs that Pring had detected in the late 1970s and early 1980s was part of a conservative backlash against the radical activism of the two previous decades. A coal mining company in 1980 sued a West Virginia environmentalist — described in the New York Times as a “blue-denimed vegetarian” — for $200,000 after he reported its illegal pollution to the EPA. The following year, the Shell Oil Company sued a California attorney for alerting regulators to lab results showing that pipes it manufactured contained a known carcinogen. In 1982, a nuclear power company in Maine filed a $4.5 million defamation lawsuit against a group that had campaigned for a statewide moratorium on the industry.

Ben Eaton, the vice president of Black Belt Citizens

This tactic faced resistance in the 1990s as legal reforms at the state level made it harder and more expensive for plaintiffs to litigate SLAPPs. Particularly effective was the enactment of so-called anti-SLAPP laws. These statutes end lawsuits fairly quickly by making it easier for courts to dismiss them, and can sometimes force plaintiffs to pay defendants’ legal fees.

But lately SLAPPs have made a comeback. Although there is no precise way to count them — lawyers don’t typically announce that they’re filing “strategic lawsuits against public participation” — examples abound. Business owners have targeted the writers of critical online reviews with abandon. Public figures displeased with negative press have been unusually quick to drag journalists into court. Politicians have taken to suing opponents over attack ads. In 2010, the for-profit Trump University sued Tarla Makaeff, a former student who had filed a class action fraud suit against the school, over what it called defamatory criticism in letters to government agencies and posts on a consumer website. Makaeff prevailed after years of litigation but decided to withdraw from the class action, which was settled this spring. The president, of course, is a prodigious practitioner of SLAPP tactics. When he professes a desire to “open up libel laws,” what he means is that he wants to make it easier to litigate SLAPPs.

In reaction to this renaissance, no fewer than six states have enacted or strengthened anti-SLAPP laws since 2014, bringing the total number of states with anti-SLAPP legislation on the books to thirty-two. But free-speech advocates still face significant opposition from critics who argue that such statutes impede a plaintiff’s constitutional right to access the court system. Several state courts have come to agree in recent years, striking down anti-SLAPP laws. At the same time, a series of opinions by influential federal judges has brought into question whether defendants can rely on state anti-SLAPP laws in federal courts.

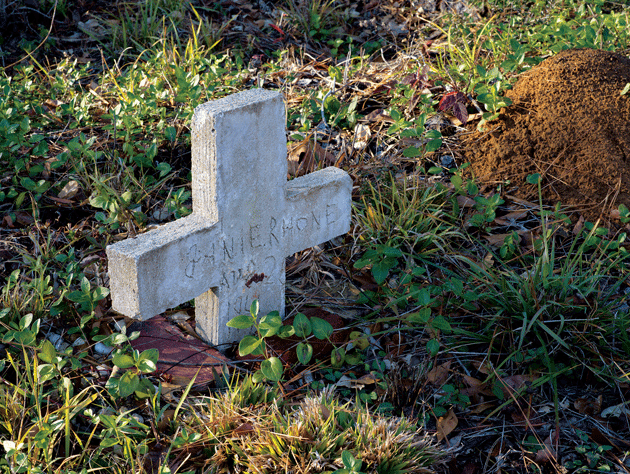

A hand-carved grave marker at the historic African-American cemetery

The new generation of SLAPPs poses a particularly grave threat to community activism. SLAPPs today imperil this key democratic institution at a precarious moment for other mechanisms of government and corporate accountability at the state and local levels. The question is whether community activists will join the likes of small newspapers and, for the foreseeable future, federal regulators — another tapering channel of local oversight — or retain their vitality as what one federal court recently called “the lifeblood of a self-governing people’s liberty.” What happened in Uniontown is a window onto one possibility.

Uniontown has a ghostly feeling to it. Porches collapse, bungalows burn down, storefronts get boarded up — and the ruins stay that way, to be consumed by brush and vines. When Calhoun, who is fifty-five, showed me around, what I got was a tour of the desolate and the defunct. “This used to be a shoe factory. That used to be a candy store. This used to be a cotton gin. This used to be a steel mill. Now it’s nothing. That used to be the Greyhound station. Who would want to come to Uniontown? This place is dead.” As if to belabor the point, the current mayor and his immediate predecessor both own funeral homes.

What Uniontown used to be, and no longer is, serves as a constant reminder of the neglect and poor decision-making that motivates Black Belt Citizens. The group’s core membership includes Calhoun along with Ben Eaton and Sally McGee — retired teachers who are, respectively, the group’s vice president and its secretary-treasurer. Two of its earliest members were the sibling duo everybody calls the Sisters. Mary Schaeffer and Ellis Long were outliers in the otherwise largely black group: white Uniontown natives in their seventies, with gray bobs and a penchant for floral blouses. Their family home dates to the 1840s, and for a time, the Sisters operated the crumbling cotton gin Calhoun had shown me.

Over time, Black Belt Citizens evolved to embrace the full range of Uniontown residents’ complaints: from possible sources of the smell that permeates the town — like the sewage system and the cheese plant — to waste in government spending, and even police misconduct. Its methods are archetypal of local, burr-under-the-saddle activism. There are strongly worded letters and complaints lodged with the Alabama Department of Environmental Management (ADEM). There are meetings and handwritten-poster demonstrations. There are social media posts aimed at attracting wider attention to Uniontown’s plight. There’s the near-religious attendance of government hearings, which Eaton conspicuously videotapes. (“Right in their faces,” as Long put it.)

An aerial photograph at the Green Group office

Calhoun and the other members of Black Belt Citizens have two basic objections to the landfill. First, they fear, over Green Group’s fervent denials, that heavy metals from the coal ash are leaching into runoff, contaminating area creeks and poisoning local flora and fauna. As she was showing me around, Calhoun called my attention to a stream across the road from the landfill. In 2013, an environmental science professor at Samford University, near Birmingham, had tested water samples and detected slightly elevated levels of arsenic. A further assessment in 2016 found normal levels of arsenic but high conductivity values, possibly indicative of pollutants. (Green Group and ADEM dismissed both results as inconclusive and inconsistent with their analyses.)

Second is the allegation of racial injustice. A 2016 report by the United States Commission on Civil Rights censured federal regulators for ignoring the inequity of off-loading the coal ash on Uniontown, and an EPA civil rights investigation into ADEM’s decision to grant the landfill its permit remains open. Then there was the African-American cemetery next door, decades old and no longer in active use. In early 2015, community members began reporting to Black Belt Citizens that landfill workers had disturbed grave markers — small stone crosses and coffin-length concrete slabs clustered amid a stand of cedar and white oak. Green Group denied the accusations, but Black Belt Citizens didn’t believe them. Calhoun was particularly incensed. She often came to the cemetery to visit the graves of her great-grandparents and a brother who had died at the age of two. “It makes you feel like, Oh, my great-grandparents might have been slaves way back in the day,” she said. “So you still own them?”

In the years before Green Group filed its defamation lawsuit, the company had met Black Belt Citizens’ objections with meetings and an exchange of views rather than litigation. The activists dealt principally with a Tuscaloosa attorney named Mike Smith, who had long done legal work for the landfill and took a leading role in engaging with disgruntled community members. Black Belt Citizens and Smith developed the kind of uneasy relationship common between small-town activists and their adversaries. The way Black Belt Citizens saw things, the meetings were heavy on self-serving explanations and light on efforts to address their concerns. Smith, in their view, was overly fixated on legal and regulatory compliance and a need for documentary proof. Still, the overall approach was one of conversation and debate — even if it wasn’t always exactly amiable.

As time went on, however, grievances festered, and the group came to see Smith as a kind of con man, changing his story whenever it suited his interests. “Mike Smith is a snake in the grass,” Calhoun told me. “He’ll say one thing and do another.” In the fall of 2015, the relationship soured further still. For one thing, the dispute over the cemetery was coming to a head. But another development seemed to bother Smith even more. Although the Black Belt Citizens Facebook page at the time had fewer than a thousand followers, its reach had started to grow, thanks in part to posts shared widely by state and national environmental organizations. A representative example:

The living around here can’t rest because of the toxic material from the coal ash leaking into creeks and contaminating the environment, and the deceased can’t rest because of desecration of their resting place.

Black Belt Citizens began to attract attention from major media outlets — the Guardian, NBC News — as well as from the Alabama chapter of the NAACP and a federal civil rights commission.

SLAPPs have adapted to combat the kind of online dissent practiced by Black Belt Citizens. In the early 2000s, companies sued chat-room critics and message-board detractors. Lately, they have turned their attention to commenters on consumer review websites. At a congressional hearing in 2016, a lawyer for Yelp named Aaron Schur testified that his company had “observed an increase in the number of businesses using SLAPPs to silence their critics,” with plaintiffs including “petsitters, flooring companies, and dentists.”

Social media, however, has been the real game changer. As Pring put it to me, “A statement in front of a government commission — that gets forgotten the next day. A simple letter to the editor — that ends up under the canary cage the next day.” But now, footage of the testimony is preserved indefinitely on YouTube, and the letter circulates globally on Facebook and Twitter.

As media attention to Black Belt Citizens was starting to swell, Smith sent the group the first of several demand letters. Green Group insisted that Black Belt Citizens retract and repudiate a series of posts on its website and Facebook page. These statements were false, the letters claimed, and constituted defamation. To Black Belt Citizens, the timing of it all seemed suspect. A crucial deadline loomed — the application for a five-year renewal of Green Group’s primary landfill permit would be due in the spring. “He wanted to try to see what he could do to shut us up,” Mary Schaeffer told me. “He knew this was all going to come around when it came to the permit renewal.” In an effort to be accommodating, the group removed some of the posts, despite Calhoun’s dissent. But it wasn’t enough.

On March 30, 2016, Smith sent the group an ultimatum. To avoid a lawsuit that could potentially bankrupt them, the Black Belt Citizens leadership would have to swear, in a court-enforceable document, that they would never again oppose the landfill and would promote its interests when asked. They would have to surrender their smartphones and other electronic devices to Green Group for a forensic audit. They would have to hand over financial records. They would have to withdraw a federal civil rights complaint. They would have to submit to questioning — under oath — about their association with other activists. To Calhoun, the message was unmistakable: Black Belt Citizens had done enough talking.

A week later, Green Group and a subsidiary filed the $30 million defamation lawsuit against Calhoun, Eaton, and the Sisters. The very same day, Green Group applied to renew its landfill permit.

Fortunately for Black Belt Citizens, a national environmental organization that they had worked with approached the American Civil Liberties Union, which agreed to take on the case pro bono. “Not every time somebody gets sued are they going to get lucky enough to get an eight-person legal team from the ACLU,” said Lee Rowland, who led the defense. But even with free counsel, the litigation process was draining. The effort it took for the group to deal with its lawyers, Rowland told me, was “a zero sum of emotional energy that they weren’t using to engage in their communities.” Group meetings grew less frequent. Attendance waned. “We kind of felt like we were at a standstill with the subject of the landfill,” Schaeffer said.

Rowland and her team had filed a motion in June to dismiss Green Group’s case, calling it a “classic example” of a SLAPP. By then, the lawsuit had taken on a taboo quality in Uniontown. Residents “were so afraid that they didn’t want to use the word ‘lawsuit’ — not out loud,” Eaton said. If they spoke of the case at all, they did so only in whispers and coded language — “it” or “the thirty million dollars” — he told me, as if speaking about it directly might get them sued too.

In October, after three and a half months, a magistrate judge in Mobile recommended that the lawsuit be dismissed. Most of Black Belt Citizens’ statements “were protected by the First Amendment as opinion and/or rhetorical hyperbole concerning a matter of public interest,” she wrote. As to the few statements the judge deemed factual, she ruled that Green Group was a public figure in the eyes of the law, and it needed to do more than claim that the statements were false. A plaintiff like Green Group would have to allege actual malice — that the members of Black Belt Citizens had knowingly lied, or had at least very seriously doubted the truth of their statements. That, the judge wrote, Green Group had not done.

In federal court, a magistrate judge’s recommendation takes effect only if a district judge adopts it, and while the parties waited for the district judge to make her decision, Green Group suddenly offered to settle. Members of Black Belt Citizens thought they had an idea why. The permit renewal application remained pending before ADEM, the state environmental regulator. “Until this thing was settled, it didn’t look like, to me, that the permit was going to get renewed,” Long, one of the Sisters, told me.

After months of negotiation, the parties settled in February of last year. On its face, the settlement was a coup for Calhoun, Eaton, and the Sisters. But it didn’t feel that way. On the one hand, they paid nothing, and Green Group was required to comply with Obama-era EPA regulations for coal ash disposal at Arrowhead, even if the Trump Administration loosens them as it has proposed. Three days after the judge approved the settlement, however, ADEM renewed the landfill permit for another five years.

I met Mike Smith one morning in the parking lot of a Piggly Wiggly in the center of Uniontown. Smith, who had driven down from his home in Tuscaloosa, is a large-featured man with a mop of gray hair, the congenial manner of well-to-do Southerners, and a backslapping fraternity chumminess. He had been eager to give me a tour of Arrowhead and prove to me that it wasn’t an environmental disaster zone at all.

It was a cool day, and away from the waste disposal site, which unsurprisingly smelled like garbage, the property — a wooded expanse of loblolly pine, river ash, and sweet gum — possessed a pastoral tranquility. Smith’s selective attention to detail, as we drove around in his black SUV, had the choreographed feel of a sales pitch. From atop the coal ash hill, he showed me the cattle his brother-in-law kept on an adjacent pasture. He made a point, knowing I had come from New York, of telling me that parts of the old Yankee Stadium were supposedly buried in the landfill. He explained that Green Group had invested in improvements to respond to community concerns — building infrastructure to reduce rainwater flowing across County Road 1 and laying a new roadway to eliminate the truck traffic that had bothered immediate neighbors. (“It’s not the best place to start a landfill, right by the road,” Smith conceded. The decision had been made under the previous owners. “That’s what happens when you have an investment banker build a landfill.”)

Despite his hucksterism, Smith evinced a genuine concern for the Uniontown community and the landfill’s place in it. He met with community members often and had made a sincere effort to give back to Uniontown, spearheading Green Group’s donation of school supplies and support of a summer festival. I was surprised, given all I had heard about him, to find that I liked him.

In the landfill’s office trailer, the grind and thrum of heavy machinery outside muffling his languid central-Alabama drawl, Smith explained the rationale behind Green Group’s decision to file the $30 million lawsuit. In the summer and fall of 2015, he had noticed an especially hostile turn in the rhetoric coming from Black Belt Citizens. He was bothered, in particular, by their claims that coal ash was contaminating area waterways and that Green Group’s workers had “desecrated” the cemetery, which he felt carried unfair racial implications.

As we talked, it struck me that Smith saw Black Belt Citizens as essentially indistinguishable from a corporate opponent. He spoke of the legal definition of “desecration” and lingered over the finer points of regulatory compliance — he is fond of pointing to Arrowhead’s perfect compliance record — and he expected everybody else to operate at that level, too. It didn’t matter to him that Calhoun, Eaton, and the Sisters expressed themselves in the heated manner of the outraged activist. “If you’re going to make that sort of statement, you ought to know whether that fact is true or not,” he said. “You don’t just say that because you’re mad.” He talked about the March 30 ultimatum as if it were the opening salvo of a corporate legal battle. “Why not?” he said. “Why not ask for everything you would want to get and take out things” during negotiations?

Facebook was the ultimate catalyst for the lawsuit, Smith acknowledged. Black Belt Citizens’ posts were starting to circulate widely enough that industry players were taking notice, and Green Group officials wanted to stem the tide of bad press. The permit renewalapplication, Smith said, had nothing to do with the lawsuit.* He suspected that shadowy third parties with outside agendas — he spoke about them as if they were latter-day carpetbaggers — were behind the posts. Some of the more outlandish demands in the ultimatum, such as forensic audits and information about contact with other environmental activists, were meant to ferret out those third parties, he told me. In essence, the thing that really bothered Smith was the prospect of Black Belt Citizens achieving the goal of community activism: alerting the wider world to its local plight.

What is alarming about the shift in speech values that Smith’s thinking represents isn’t that it will enable evil CEOs and their soulless corporate attorneys to enact some nefarious agenda. Smith isn’t a villain who set out to sidestep the First Amendment. I don’t think he believed he was filing a SLAPP — a quality he shares with most SLAPP plaintiffs. “They’ll say, ‘We never intended to do that. We just wanted to set the record straight,’ ” Pring told me. The trouble is that this kind of reasoning normalizes behavior that suppresses individual speech. Instead of filing suit, Green Group — a national corporation with operations from North Dakota to Guam — could have leveraged its superior financial position to challenge the truth of Black Belt Citizens’ Facebook posts. The company could have taken out advertisements touting the perfect regulatory compliance record Smith is fond of celebrating. It could have engaged in its own social media campaign to counter Black Belt Citizens’. Instead, it sent a message. The members of Black Belt Citizens had to be careful about what they said; speech that Green Group considered false or out of line would come at a steep price.

No matter how frivolous, lawsuits are menacing things — the hyperbolic sums, the uncertain byways of the law, the Delphic pronouncements of black-robed judges — and they have a tendency to haunt the people subjected to them, like trauma or an inauspicious omen. One evening, during a conversation with Eaton, McGee, and the Sisters, Calhoun said, unprompted, “I think we should all go see a psychiatrist.” At first she laughed, but when I prodded her to explain, wariness crept into her voice. “Fighting against all this stuff . . . ”

The lawsuit was a month and a half behind them, and it had ended in the group’s favor. Still, the process had taken its toll, and for the members of Black Belt Citizens, it was hard to discern a victory. “I’m glad it’s over,” Eaton said. “But at the same time, they used that to intimidate us, to hold us off for the timing of having their permit renewed. That was the whole plan: keep you busy doing one thing while we’re doing something else.”

The next evening, my last night in Uniontown, I attended a city council meeting. City hall looked as if it hadn’t seen a renovation since the 1970s: threadbare wall-to-wall carpeting, fake wood paneling, yellowing photographs of figures from Uniontown’s political past. Eaton arrived late. He looked exhausted, almost pained, as he walked stiffly to a seat in the front row and began videotaping. A few years earlier, in an effort to alleviate pressure on Uniontown’s swamped sewage system, a contractor had constructed a $4.8 million spray field, on which sprinklers disperse wastewater to be absorbed by the soil. ADEM had since declared it to be unusable because of the area’s unusually dense geology. Now the same contractor was proposing to install a wetland, yet another multimillion-dollar, percolation-dependent wastewater treatment system. Black Belt Citizens had helped arrange for two experts to discuss less expensive and more effective alternatives. The council members listened quietly as they discussed the town’s options. After a few perfunctory questions, the council voted without debate to “explore” the contractor’s wetland proposal.

After the meeting was over, Eaton, the Sisters, and several other members of Black Belt Citizens lingered, chatting beneath the hum of the fluorescent lights. Sally McGee gave me a fatigued look. “Same old — how it always is,” she said, her voice sagging.

Amid all the talk, I hadn’t noticed Calhoun leave. I found her outside a few minutes later, sitting on a low brick wall in front of city hall. She looked defeated in a way I hadn’t seen before. She had never intended to carry this weight for her town. “All I wanted is just to live my everyday life,” she’d told me at one point. “I don’t like fighting or doing all this different stuff. But somebody’s got to do it.” The lawsuit had only added to her burden. It was palpable in that moment, her shoulders bowed, her hands folded in her lap, her gaze fixed somewhere in the middle distance as the purple dusk gathered around her.