According to one Norse myth, the gods needed a wall. Asgard, their kingdom, had once been surrounded by barricades, but a war had destroyed them. When the gods decided to erect a new wall, a builder appeared out of nowhere and offered his services. Loki, the trickster, suggested that the gods accept his proposal but set an impossible deadline. When time ran out, they could send him on his way, thereby getting the lion’s share of the wall for free.

The builder accepted the terms and set to work. Accompanied by his trusty horse, he made quick work of the wall; he was perilously close to completing the stone loop around the kingdom before his time was up. Desperate, Loki transformed himself into a mare to lure away the builder’s horse. The builder was outraged. This was when the gods realized, to their horror, that he was actually a giant — their sworn enemy — in disguise.

The fence at the border checkpoint between Storskog, Norway, and Borisoglebsk, Russia © Lev Fedoseyev/ITAR-TASS/Alamy

Thor bludgeoned the interloper to death with his hammer. The wall remained, but the gods’ dishonest dealings set in motion Ragnarok: the fall of the empire and the end of the cosmos.

Border walls have been around as long as the gods themselves, guarding our cities and castles. They fell briefly out of favor, but at the moment, they seem to be enjoying increased popularity in such far-flung locations as Myanmar, France, Bulgaria, Pakistan, and, of course, the United States. Unlike those of yore, erected to keep out marauding invaders, today’s walls are designed to guard against desperate refugees and migrants. Governments are launching efforts to strengthen overburdened borders as people seek to escape everything from war and famine to drought and rising seas.

This revival comes at a time when the argument against walls seems particularly convincing: experts have found that walls have never really worked, and they often seem to presage not an empire’s perpetuity but its collapse. Walls offer the promise of absolute protection, but they almost always fail to deliver. Still, we build them again and again. Last winter, I traveled to Norway to see one of Europe’s newest and most infamous projects in hopes of learning what it could tell us about our age-old impulse to both wall ourselves off and wall ourselves in.

The Arctic town of Kirkenes, in Norway, is where land meets sea, where water meets ice, where taiga meets open tundra, where even the membrane between day and night is always shifting. There are days without darkness and other days when the sun barely glimmers at the horizon. The town sits on the border between Norway and Russia, a 121-mile line through rock, river, and permafrost. On a cold, clear day in late winter, I parked in a small lot near the Storskog border checkpoint, nine miles outside town on a well-paved road that cuts through the Arctic hinterlands. Across a frozen lake, I could see Russia, dappled with petite arctic birch and spruce. It looked just like Norway, except it had a sheen of magic simply for being an elsewhere.

In the summer of 2015, migrants — first mostly men from Afghanistan and Syria, then their families, and eventually people from other parts of the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia, too — began arriving at this checkpoint. That June, to help lift the burden on Mediterranean countries on the front lines of the migration crisis, Norway had pledged that it would take in eight thousand refugees. (In total, more than a million people would seek asylum in Europe that year, double the numbers from previous years.) Granting asylum entails a lengthy screening and transfer process, but many migrants took Norway’s statement to mean that the border was open — and that they’d better cross before the eight thousand spaces were filled.

Migrants cross the border in Storskog © Cornelius Poppe/AFP/Getty Images

Seeking to circumnavigate the clogged routes of the Mediterranean, they chose an alternate way to the safety of Europe. Some migrants had come directly from war zones or refugee camps farther south; others had been living in Russia for months or even years, and feared being sent back to Syria or Afghanistan once their visas expired. Many made their way to the Russian city of Murmansk, where, racing the coming winter, they hid from immigration authorities in local hotels and hired smugglers to get them to the other side. Russia doesn’t allow individuals across the border on foot, so the smugglers provided bicycles, charging five hundred dollars to get people to Kirkenes. In The Bicycle Pile, a documentary about the arrivals, a Russian hotel owner recalls that smugglers covered the city with posters showing Norwegian women holding signs that said come to us. we will protect you and your family. Social media helped the images spread around the world.

Both countries are supposed to check paperwork and make sure crossers have proper visas for the other side, and yet when the asylum seekers showed up, Russia simply let them pass. Norwegian officials felt that by allowing people to cross without permission, Russia was exporting its problem to Norway. A few hundred came to Kirkenes the first month; by the fall, it was thousands, and the community scrambled to accommodate the new arrivals. By November, more than 5,500 migrants from some fifty countries had come to this town of 3,500.

Oslo asked Moscow to take the refugees back, but in the end only some three hundred people were returned to Russia. In one chilling scene in The Bicycle Pile, a Syrian woman with two children is taken across the border zone back into Russia. It’s dark and snowing. She sits down with her kids in the middle of the no-man’s-land between the Russian and Norwegian checkpoints, refusing to move.

After several months of debate, the governments agreed that any migrant trying to cross without the proper papers would be stopped by Russian authorities. The word got out on social media, and the flow stopped. “They disappeared,” said the mayor of Nikel, a town on the Russian side of the border. Then, four months after the last asylum seeker crossed, Norway’s government announced that the nonexistent problem required a bold solution.

It’s important to send signals,” Espen Teigen, the political adviser to the minister of immigration and integration, told me. He is also a member of the Progress Party, the Norwegian, and thus relatively liberal, expression of the nativist wave sweeping the globe. Teigen was concerned about the number of migrants coming into Europe, the cost of caring for them, and their failure to assimilate into society; he believed the barrier would serve as a counter to the messages of welcome that other leaders on the continent were sending.

But the signal was faint. The wall — actually a chain-link fence — would stretch only six hundred feet. Still, most people and politicians in and around Kirkenes were outraged. Residents had rallied to support the asylum seekers, collecting donations and opening their homes, schools, and community centers to them. The fence negated those efforts and alienated the townspeople from their Russian neighbors. (In the United States, attitudes follow a similar pattern: the closer conservatives live to the US-Mexico border, the more likely they are to oppose a wall.) “This is an example of incompetence, historically and politically,” Rune Rafaelsen, the mayor of Kirkenes, told me. The fence cost $830 per foot, about $500,000 in all — not much for a public-works project. But to most locals, it was an expensive and abrasive imposition intended to stop a problem that had been solved.

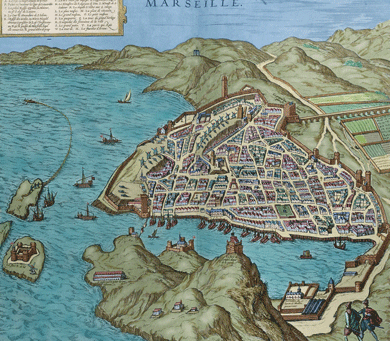

A sixteenth-century map of Marseille, France © Private Collection/Tarker/ Bridgeman Images.

As it happens, there was already a wall on this very border. Early in the Cold War, the Soviet Union began erecting fences on its borders. Rather than keeping people out, they were intended to prevent those inside from escaping a brutal regime. Norwegians stayed away, but in 1965, a twenty-seven-year-old American walked through the Storskog checkpoint and up to the Russian authorities, hoping to get a stamp in his passport and bragging rights back home. Instead he was carted off to a Soviet prison, and died within a year.

Construction on the Storskog fence began in August 2016 and was finished about a month later. (The project had been delayed when surveyors realized that the fence had been built an inch or two into the buffer zone between the countries and had to be moved.) Now the “wall” stands several miles from the old Soviet border fence, which was recently updated with surveillance cameras, though its current purpose is unclear. Today, on the frozen cusp of northern Europe, the two fences stand opposite each other, as if in a face-off.

Outside the checkpoint, the ground was frozen with ice, which splintered underfoot like shards of glass. There was an uncanny atmosphere of temptation, rooted in the forbidden. Signs told me not to take pictures, which made me nervous that I would forget and do so all the same. I also worried that I might accidentally step over the line and violate international law, as if the border had a subliminal pull. Milan Kundera once described vertigo much the same way: not so much the fear of falling but the desire to jump.

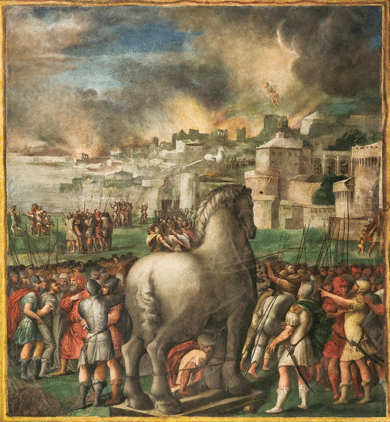

A fresco of Troy from the Aeneid, Canto II © Nicolò dell’Abate/Galleria e Museo Estense, Modena, Italy/Ghigo Roli/Bridgeman Images

My phone pinged with a welcome message from a Russian telecom network, and I stepped inside the checkpoint — a low-set, caramel-colored building with a snow-covered roof. At a conference table decorated with miniature Russian and Norwegian flags, I sat down with Stein Kristian Hansen, the chief of the border station. Tall and blond, he poured coffee into mugs decorated with cartoon elves frolicking on the border. The mugs, he told me, I was allowed to photograph. Hansen explained that he had been asking for a fence ever since he took the job eight years ago. His desire “had nothing to do with migration,” he said, “but with security.”

In 2017, there were 265,000 crossings at Storskog, mostly Russians coming in to shop. (This was a massive increase from the Nineties, when only about 8,000 people crossed at Storskog each year.) When the government announced its plans, Hansen was most interested in the proposal for a retractable gate — one he could open and close with the touch of a button, so that, in an emergency, he could seal the border to stabilize the situation and protect the officers who serve alongside him. But he was certain that the fence would do nothing to curb a future flow of refugees. For one, people could simply walk through the forest and circumvent the checkpoint. Hansen lives in Kirkenes, and he is perplexed by the outrage against the wall. “They think it’s a message to Russia,” he said. “But Russia is a big country with a powerful army.” He gestured to the fence and smiled. “This fence isn’t going to stop Putin.”

Elf cups drained, Hansen and I walked outside. The fence was slightly burlier than one at a schoolyard, with tight chain link secured to metal posts set some three feet apart. It sliced a path through a low boreal forest, which had been clear-cut about ten feet on each side to allow for a clear view of anyone approaching. To the west, Lake Neitijärvi formed a natural boundary. To the east, the fence crested a slight hill and disappeared from sight, creating the impression that it continued on forever.

The Great Wall of China © Waldemar Abegg/akg-images

Recently, the border has become a tourist attraction. According to Lars Georg Fordal, the head of the Barents Secretariat, an organization that promotes cross-border cooperation, local tour operators use it as a selling point. In the summer, visitors can lunch on smoked salmon at a nearby restaurant with views of Russia and the lake. Fordal also told me that cruise ships dock at Kirkenes so passengers can travel to the border and say that they saw Russia with their own eyes. The fence promises to draw even more visitors.

Hansen showed me the slatted metal gate. It was open, nestled against the fence; with mechanized wheels, it is designed to slide shut across the tarmac. Unfortunately, he admitted, the design was off. The bottom wasn’t high enough to clear the snowpack, so the gate got stuck in place every time there was a freeze. For now, they kept it open at all times. “They’ll rebuild it during the summer,” he said with a shrug, giving the fence a final little jiggle. We turned our backs toward Russia and, breath freezing against our faces, walked back inside.

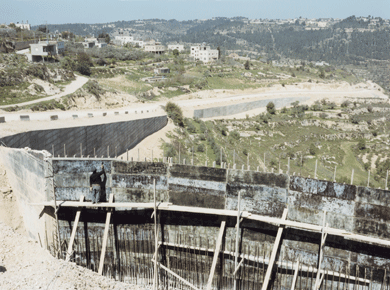

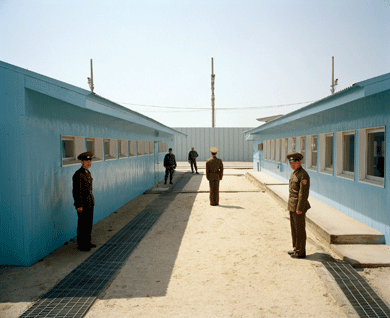

Throughout history, humans have folded walls into myths and legends while also erecting walls to buttress geopolitical borders and project imperial grandeur: the wall that separated the lovers Pyramus and Thisbe, the gilded walls of the Incas, and the city of Troy, whose walls were outwitted by a horse. The Great Wall of China, actually nearly four thousand miles of semiconnected segments and additional barriers, was meant to keep out nomads from the steppe. In the second century ad, the Roman emperor Hadrian conceived of a seventy-mile stone fortification at the upper reaches of his empire — now in the United Kingdom — in order to manage trade, keep out the barbarians, and advertise the power of his empire and its ruler. Meanwhile, other walls were designed to keep people from leaving. The Mur de la Peste (“Plague Wall”) in Marseille, France, was built to contain the disease, and thus the diseased. More recently, repressive regimes such as those of East Germany and North Korea (and, of course, the Soviet Union) built walls to keep people from fleeing. Many of these walls largely failed in their expressed purpose. Guards along the Great Wall of China were often bribed to gain entry; the barbarians breached Hadrian’s wall and killed a general and his troops.

In the Arctic north, borders hardly existed at all. Indigenous nomadic people had lived in the Scandinavian Arctic for thousands of years, believing that land was a communal resource. Today, the Sami people, the descendants of these tribes, fight to herd their reindeer over borders drawn in 1826 in direct opposition to their way of life.

Cascade, oil on linen by Gregory Thielker from Unmeasured, his series of paintings of the US-Mexico borderlands. Courtesy the artist and Castor Gallery, New York City

In Norway, border walls weren’t erected until feudal times, when it became a bargaining chip for several larger empires. As the kingdom consolidated and began to face threats from outside, Norwegians began building walls, and now the country is dotted with their relics. Last year, Norway celebrated the 450th anniversary of the founding of Fredrikstad, one of Europe’s best-preserved fortified towns. In 1567, when Norway was still a part of Denmark (a period now referred to as the “four-hundred-year-long night”), the Swedes were at war with the Danes, trying to win key territory and coastline. When the Swedish army burned down the city of Sarpsborg, King Frederick II ordered that a new city be constructed at the point where the Glomma River bends toward the North Sea. This was a key trading point and also a strategic defensive zone with a 360-degree view of approaching threats.

The rampart walls of Fredrikstad were built in a star shape, according to the Dutch style, with a moat around the perimeter. There were 200 cannons and 2,000 guards — ten soldiers for every cannon — stationed atop the wall, on twenty-four-hour patrol. Each night, the drawbridge was raised, sealing the city, and it was not lowered until the king gave the command the next morning. (He was a known drunk who slept late, often leaving farmers stuck at the city gate as they waited to take their flocks out to pasture.)

From above, Fredrikstad is stunning and resolute; the rippling river forms its western border, and to the east, the three star points of its walls push outward as if taking aim at the green horizon. For nearly 150 years, Fredrikstad was on guard against potential threats, but perhaps because its defensive reputation preceded it, the city was never attacked. Then, in 1814, the Swedes came up the river by boat. After one day of battle, the city waved its white flag.

“Denied Horizon, Beit Jala, Palestine, 2012,” by Noel Jabbour. Courtesy the artist.

During the Second World War, the Germans occupied Norway and laid siege to the Finnmark region; Kirkenes became one of the most-bombed towns in the war. It was the Soviet Union that liberated Kirkenes from the Nazis, and when the Germans capitulated, the Russians went home. “They didn’t stay. This is still very much remembered,” Lars Georg Fordal of Barents Secretariat said, emphasizing a fact that is prominent in the local historical consciousness. The border has always been peaceful; Russia and Norway have never been at war, although in recent years, relations between Russia and Norway — that is, between Moscow and Oslo — have become frosty, particularly after the annexation of Crimea. The migrant situation only made matters worse.

The border between North Korea and South Korea (bottom) © Martin Parr/Magnum Photos

In 2015, two political scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, surveyed dozens of border walls built around the world since 1990, mapping the fortifications to try to understand common trends. Not only did the rate of wall-building increase over the period, but, they found, the building projects were becoming more ambitious. They also found that walls weren’t built in places that suffered from disproportionately high terrorism rates or in areas under territorial dispute. In nearly all cases, they were built on borders between countries with significantly different economic standing, often a non-Muslim country and a Muslim-majority country. Nevertheless, most border walls of the current resurgence were built, the research found, in the name of security.

For those who live in border towns, the boundary is mostly understood as a construct devised by those in power, who often live far away. The distance may lead to a kind of reverse provincialism. “Kirkenes is the geopolitical center of Norway,” Mayor Rafaelsen insisted. “There’s nothing happening in Oslo.”

As Rafaelsen sees it, countries that share economic interests and complex logistical ties are less likely to go to war. He is rooting for joint industrial projects in the Barents Sea, where Norway’s oil and gas reserves are located. Given Russia’s feeble industrial output and economic challenges, Rafaelsen believes that cross-border cooperation would benefit both parties and, most importantly, strengthen Norwegian national security. “The wall,” he declared, “is not the answer.”

One evening in Kirkenes, I joined Rafaelsen and the staff of the Independent Barents Observer, the local online daily, at their tidy office in the center of town. It was happy hour, and a group of journalists, municipal employees, and neighbors crowded into the small room, pulling up folding chairs and passing around some beer and chips. “Everyone agrees that it’s a symbolic fence,” insisted Atle Staalesen, the paper’s managing editor. “It doesn’t have a function at all.”

Indeed, my hosts explained, the fence was an affront to their very identity. Crossing the border is not only a fact of life here but also the draw; both Staalesen and his colleague Thomas Nilsen moved to Kirkenes because of its proximity to Russia. People in town frequently go to Russia for shopping, they told me, or to get clothes tailored or shoes cobbled.

“I’d often just go there to meet a friend for a beer,” Nilsen said, “then come back that night.” The fence and the increased border security have changed that — and then Nilsen found out that his name had recently been added to a no-entry list for Russia, another sign of the friction between Moscow and Oslo.

The border has always been an integral part of the region’s identity — indigenous migrations, mutually beneficial commerce, a sense of being at the place where the West meets the high Arctic and Russian Orthodoxy meets Protestantism. Here in the far north it can be difficult, in flat light, to distinguish between land and ice and sea and sky, and the notion of a dividing line seems peculiar. How could it be otherwise? Borderlands dwell in paradox: the landscape might be the same on either side, but the geopolitical reality is vastly different.

Even so, geography encourages cross-border affinities. Oslo is a twenty-three-hour drive from Finnmark, which requires passing through Finland and Sweden. The closest major city is Murmansk, in Russia — which as it happens is twenty-three hours from Moscow. The average person in Kirkenes, Nilsen explained, doesn’t see the border “as a geopolitical designation. In Oslo, they do.”

We had consumed many rounds of Russian beer, purchased on the other side for about a dollar a can. (Norwegian beer costs eight times as much.) Brede Sæther, a businessman and the landlord of the Independent Barents Observer, suggested a nightcap at his place. Six of us followed him through downtown, where dusk cast pale cornflower light onto the snow. Sæther led us into his back yard and along a neatly shoveled pathway through hip-high snow. He knelt down and, with a grunt, yanked up a great metal door in the ground. “Here,” he bellowed theatrically, with a slight backward sway, “is my bunker!”

A staircase descended more than a story underground and deposited us in a massive cavern of around a thousand square feet, an echoing, apocalyptic ballroom. The main chamber had twenty-foot ceilings and connected to half a dozen other rooms, some blocked by metal doors, others accessible via a low-ceilinged hallway. “There are bunkers all over Kirkenes,” said an awestruck Staalesen, “but I’ve never seen anything like this.”

During the Second World War, Kirkenes was on the northernmost front, and there’s a whole underworld in the city, built by the Nazis — and perhaps by their Russian prisoners of war — to defend against Soviet forces. Sæther tossed us each a beer and called us over to a narrow, circular stone chamber that reached all the way up to the crust of earth above us, where we could see an opening onto the evening light. He had discovered this tubular room only last year, when a crack running beneath an adjacent wall inspired him to take it down with a jackhammer. He soon realized that the room was filled with the garbage that he and his family had been dumping down a mystery hole in their back yard for decades. Because of its shape, he deduced that the room had been a gunner station. “We thought there might be treasure!” Sæther said, laughing. “But it was just my own trash!” He slammed his hand against another wall, which seemed to promise more mystery just beyond. “This summer, I’m going to knock it down.”

Sæther’s remark reminded me of a conversation I once had with an undocumented family living in a studio apartment in the Tenderloin, in San Francisco. I’d asked why they’d come to the United States. “We just always had this curiosity,” the mother said. The border, she suggested, had an appeal that was irrational, almost mystical. “We just wanted to know,” she recalled, placing her hand against her forehead as if scouring the horizon, “what is it on the other side?”

Later, I read that while the Nazis were building the bunker network in Kirkenes, Adolf Hitler issued Directive 40, which called for another defensive public-works project: the so-called Atlantikwall, a fortification that would surround the sea perimeter of the Nazi empire. In March 1942, he conscripted 260,000 soldiers and civilians to build the wall, imagining it as a physical barrier between the Third Reich and the rest of the world. In the end, the project was a series of unconnected fortifications along the coasts of Germany, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. Hitler boasted that the wall was impenetrable, but in 1944 the Allies would manage to breach it in a single day.

When migrants first started crossing the border into Kirkenes, the Norwegian government commissioned a series of social media posts to discourage the influx. “Why would you risk your life?” the posts read in Farsi, Arabic, English, and French. The goal was to “inform people of the dramatic consequences of embarking on such a large journey,” explained Teigen, the political adviser. If online rumors helped to facilitate migration along the Arctic route, the thinking went, perhaps the same medium could be used to stop it.

On my last morning in Norway, I went to meet with Edin Krajisnik, who was working as a refugee-resettlement adviser with Norwegian People’s Aid, a humanitarian and charity organization. His office in downtown Oslo is a few blocks from the building where, in 2011, Anders Breivik, a radicalized former member of the Progress Party, set off a bomb. He went on to massacre dozens of leftist Labor Party youth leaders on a nearby island, hoping his actions would spark an anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant revolution.

“There are more invisible walls in Norway than visible ones,” Krajisnik said. These take the form of repressive, anti-immigrant laws, of government-sponsored Facebook posts discouraging migration, and even of anti-immigrant public opinion. When he came to Norway in 1993 as a young refugee from Bosnia, Krajisnik was met with open arms. Today, he lamented, new arrivals face a different reception. The spike in anti-immigrant fear “coincided with an increase of images of ISIS on the internet,” he told me. “They’re seeing more images of terrorists than they are of suffering children.”

This embrace of the internet — of walls that are essentially virtual, made of algorithms rather than steel and concrete — as a political tool is perhaps understandable. Physical barriers are moving toward obsolescence. Yet we keep building them anyway. Why? In Walled States, Waning Sovereignty, the political scientist Wendy Brown asserts that such walls are a reaction to “the dissolving effects of globalization on national sovereignty.” The more enmeshed, known, and mutually dependent we are, the more we fear that the nation-state itself is toppling into irrelevance. Meanwhile, the internet also helps propagate fear — of terrorism, of the other — with racist media, hate groups, tweets, and viral content thriving online and further stoking irrational paranoia. The wall craze, like global nationalist movements, can be seen as a backlash, a call for clear, knowable boundaries in an increasingly porous world.

Perhaps in response, walls loom large in contemporary popular culture. In the world of the Hunger Games trilogy, walls protect the bounty of the capital. On Game of Thrones, an immense, icy barrier shields civilization from the unknown, sinister evil on the other side.

Politicians, too, invoke this imperiled sense of identity in their calls to close off borders. Forced migrants are moving around the world in record numbers, and the refugee crises are steadily moving toward the global North, into wealthy nations whose fixed borders have traditionally defined them. When millions of refugees cross from one sub-Saharan country to another, there is no threat to the United States and Norway. In such cases, governments offer humanitarian rhetoric, aid packages, and resettlement opportunities, which do little in the face of mass migration. But a mass of refugees clambering over your own borders is something altogether different. Images of these migrants can evoke a humanitarian response but also populist fear. If a nation seems to be coming apart, perhaps a wall can hold it together. We convince ourselves that we’re in a state of perpetual siege; we turn the state into a bunker.

After my meeting with Krajisnik, I stopped at Akershus Fortress, the old walled center of Oslo, built in the thirteenth century to defend the city against the Danes and the Swedes. The cobbled grounds, which resembled something between a college campus and a cemetery, led to a hilltop, with the glistening harbor visible over the lip of the wall. In spite of multiple attacks from the Swedes, the Scots, and the Danes, Akershus was never successfully besieged. (It was, however, given up to the Nazis without a fight.)

Up on the rampart, I stood within fortifications used to defend against a knowable enemy. Today, we are assaulted by threats that we cannot always see, and in our fear it’s as if we’ve become sentinels on our own walls, ever ready for battle.

I thought of the fences of yesterday, and the fence of today. There was something absurd about traveling all the way to Norway to see a fence so small. Yet its flimsiness was somehow fitting: it was, after all, no more than a screen onto which anyone could project needs, fears, and dreams.

When I was ready to leave, I somehow took a series of wrong turns and found myself stuck in a maze. Surely this path will lead me out, I kept telling myself, but instead, every turn I took led back to the wall itself. There was still something ominous about being trapped amid the looping pathways and the trilling Akershus birds.

My flight was leaving in a few hours, so I pulled out my phone and followed my blue-dot avatar out of the fortress and back into the city, onto the train, through passport control, then finally up into the air. From the plane, everything below was just sea and ice and then land again; the distance rendered the borders invisible.