Discussed in this essay:

Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty, by Jacqueline Rose. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 256 pages. $26.

Motherhood: A Novel, by Sheila Heti. Henry Holt. 304 pages. $27.

My son was born on the night of November 8, 2016. Because he was three weeks early, I had not voted absentee. All day I repeated, “I can’t believe this man is preventing me from voting for our first female president.” A few hours after the birth, I instructed my husband to look at his phone and find out what was happening with “my main bitch Hillary.” Concern crossed the nurse’s face. “You know, it’s not looking good,” she said. “I’m so sick of this liberal anxiety!” I replied. “She’s got this in the bag!” The nurse raised her eyebrows and fiddled with the IV; a trained professional does not argue with a woman who is recovering from a thirty-seven-hour labor. From across the room, my husband cleared his throat. “Trump won Ohio,” he said.

The hospital was swamped with babies. The doula said there was a supermoon. There were no beds available in the maternity ward, so we were moved to the inside half of a double on a general floor, approximately the size of a broom closet. “He won North Carolina.” The closet was not big enough for my husband and the bassinet, so I sent him home and asked the nurse to wheel the bassinet next to my bed. The cafeteria was closed. I was very hungry. I looked at my phone. Trump had won Florida. In the night, the baby on the other side of the curtain cried, which made my baby mewl. I was too weak to pick him up, so I rubbed his stomach and said, “Sh, sh.” I looked at my phone. Trump had won the election. I fell asleep. In the morning, I had a text from a friend: “CONGRATULATIONS YOURE A MOM IN A NEW FASCIST AMERICA!!!! But seriously all my love.”

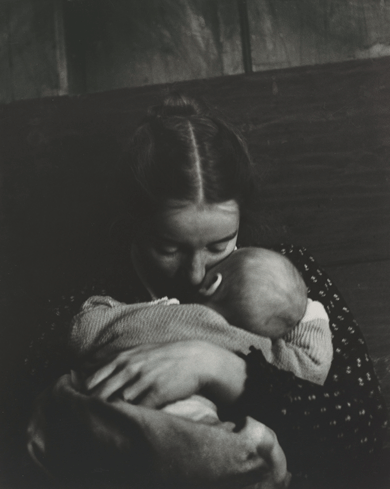

“Mother and Child,” c. 1940, by Nell Dorr © Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. Gift of the Estate of Nell Dorr

My husband showed up. I was starving, stitched, bleeding, unable to walk, and my abdominal muscles had separated, but he had been up alone all night and looked crazed. He handed me some nuts. My mother arrived, and my in-laws. They took photos. A lactation consultant came through and watched the baby fool around. Through the curtain, we heard our roommates basking in Trump’s victory and mocking the distressed posts of their Facebook friends. My husband swears that the other dad cooed to his daughter, “You’re going to make America great again!” We petitioned for an early discharge, and at one in the morning loaded up the car, like criminals.

I heard that other people who had babies around the same time became fixated on politics, obsessed with making the world better for the new life they had made. Their social media feeds grew ever more fervent and passionate, and they took their infants to protests and marches. I skipped the protests. I read the news all the time, but I couldn’t figure out what it had to do with me. Other people were mourning the rise of nationalism, xenophobia; Rudy Giuliani was going to be secretary of state. I had never been happier. I was high on oxytocin. Sometimes I cried when I looked at my baby. He was perfect. I had gone to hell and come back with him. Sometimes I nodded off and woke up screaming because I feared I had dropped him off the side of the bed. At other times I joked that he was going to grow up, build a time machine, travel back to the day of his birth, change the outcome of the election, and get himself born, but that was just a way of trying to connect two unrelated events.

There was an ugly hematoma on the back of my baby’s crushed, pointy head, and whenever I looked at it I felt guilty for not getting him out sooner. During labor, when things were hardest, I’d said over and over, “I can’t.” In the days after, the shame of having wanted to give up haunted me. Now I think that’s what being a mother is: it is something that you can’t possibly do, and yet you keep doing it anyway. That doesn’t mean you do it well — or maybe it’s just that doing it well doesn’t look as you expected it to. According to D. W. Winnicott’s concept of the “good enough” mother, it is important to fail at mothering, or else your child will not pass from illusion to reality. The mother teaches the child to handle frustrations by being one.

Jacqueline Rose, a British literary critic who writes often about psychoanalysis and feminist theory, is interested in maternal failure writ large. In her new book, Mothers, which extends an essay she published in the London Review of Books in 2014, she laments the undue symbolic burdens we place on mothers. We scapegoat mothers for “our personal and political failings . . . which it becomes the task — unrealisable, of course — of mothers to repair.” We want mothers to “hold up the skies,” to make things “bright and innocent and safe,” to “carry the burden of everything that is hardest to contemplate about our society and ourselves.” They can’t. We must let them fail at what we ask so that we can learn to ask for something else.

Mothers receive too little and too much attention, or the wrong kind of attention. They are ordered to “return to their instincts and stay home” or “to make their stand in the boardroom,” but in either case are excluded from “public, political space,” where “the shameful debris of the human body is unwelcome.” Mothers bring mess with them everywhere they go — spilled milk, sticky fingers, too many tote bags. A friend of mine who is not a mother recently complained that her seatmate on a long international flight had changed a diaper on the tray table, as if it were a public health hazard. Yesterday, while my son was screaming himself to sleep on a short domestic flight, I realized that tears are another form of human debris. A mother receives pity and disgust for bringing them into public view. But far worse is the conflict that arises within a mother when a child cries in public: the feeling of failure and anxiety, the concern for the child, the effort not to shame him, and her attempts to remind herself that there is nothing wrong with crying, even if it’s bothersome for whoever else is around. What are tears but the universal expression of frustration and rage?

“63 Objects Taken from My Son’s Mouth,” by Lenka Clayton, who collected these items when her son was between the ages of eight and fifteenth months

Mothers themselves are expected to feel only along a narrowly approved continuum, and to accept, with mournful resignation, sacrificing their children for higher ends. (Rose admires a novella by Colm Tóibín in which Mary runs away from the sight of Jesus on the cross.) But mothers can “see the reality of the cruel political world they are being asked to gestate” and thus “expose misfortune as injustice.” Rose cites as examples the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, whose children were “disappeared” in Argentina’s Dirty War; Doreen Lawrence, whose son was murdered by London’s Metropolitan Police in 1993; and British women who demanded suffrage during the First World War “as the fair if partial recompense for having been expected to send their sons to war.”

I assume that there are those who think that mothers have too much social or public authority. It’s lose-lose-lose: the culture deifies and loathes mothers in equal measure, and treats childless (or, as some would have it, “child-free”) women with suspicion and contempt. It wasn’t enough for Hillary Clinton to be secretary of state; she was also “a mother and a grandmother.” But the world is not set up for women with children to succeed professionally. In the United States and Europe, women with children make less money than men and women without children. Rose cites startling statistics: 54,000 women lose their jobs every year in the UK because of pregnancy; 77 percent of pregnant women and new mothers experience workplace discrimination.

So often mothers are accused of retreating, narcissistically, from the political world to protect and care for their offspring. (This was Rebecca Solnit’s argument in her essay “The Mother of All Questions,” which appeared in these pages: that she chose a life of public activism over the retreat of the family.) Rose, however, thinks that motherhood can be a model for a broad and inclusive politics. “To be a mother . . . is to welcome a foreigner,” she writes, a notion that she connects to migrant crises and other international emergencies, and in which she sees a possible “foundation for a different ethics, and, perhaps, a different world.” Rose is not naïvely suggesting that holding someone else’s baby makes you feel the same as holding your own. She’s asking us to see “a mother’s body and the public world all around her” as “indissolubly linked.”

Rose adopted a daughter from China, and this experience helps her see a fundamental truth that the intimacy of birth can hide: “An adopting mother knows somewhere deep down that she does not own her child, something I have always seen as a caution, a truth and a gift.” Even children who were umbilically attached to their mothers are radically distinct. One of the terrors of pregnancy is the feeling that something is growing inside you of its own volition. You are joined with it, which is to say that it is separate. From a very early age, the child has his own goals, agendas, projects, and desires. Rose quotes Simone de Beauvoir:

The child brings joy only to the woman who is capable of disinterestedly desiring the happiness of another, to one who without reversion to herself, seeks to go beyond her own experience.

A mother’s job is to love her child in such a way that he can love other people, specifically other people who treat him with kindness. It is an insane task to undertake, to give (almost) everything to someone who will, without thanks and probably with some rudeness, depart and go live his life elsewhere. It becomes easier to bear if one takes up Rose’s image, seeing the child not as a thing you own but as a person passing through, in need of temporary refuge. That you will fail at providing this refuge is part of the deal.

Mothers, for Rose, are the “original subversives”; they give the lie to the clichés and myths that would suffocate them. One myth: that they exist only for their children. Another: that they neither hate nor desire. (Rose is very good on the romance of breastfeeding.) Yet another, the most awful of all: that they can fix everything, make everything okay. Children slip, trip, fall, and worse. I think of the mothers who watched, unknowing, while their daughters were molested by Larry Nassar. I think of “bland American” Charlotte Haze, who cottons on to Humbert Humbert’s schemes just before a hit-and-run removes her from the plot. Was she a bad mother? Or only helpless, in Rose’s terms, incapable of making the world safe? Is a mother responsible for the dirty water in the tap, for the bullets that fly over her kid’s route to school? Is she in charge of school funding, health care costs, job growth? Opioids, bullies, toxic friendships, school shooters? Mall shooters? Movie-theater shooters? Nightclub shooters?

To be a mother is to struggle to save — while also knowing that you will fail to save — your child. To be faced with the prospect that the world is not getting better, that there will not be a better life for the lives you have made.

But seriously all my love.

My mother occasionally used to remark that having brought me into the world, she was on hand to usher me out of it. When I was little, I heard this as anger. Now I understand that it was simply a statement of power. Some great portion of misogyny, both male and female, springs from resentment of the all-powerful mother. Rose suggests that the conservative doctrine of self-reliance is a denial of past helplessness. She quotes Adrienne Rich: “There is much to suggest that the male mind has always been haunted by the force of the idea of dependence on a woman for life itself.”

Bringing someone into the world, making a home for someone in the world — these are enormously powerful acts, maybe the most powerful acts. A person who has the power to do that has the power (if not the right) to do anything. A person who refuses to do that is just as powerful. As Rose writes, “By refusing to be mothers, women have the power to bring the world to its end.”

But what about women who might like to refuse to be mothers but aren’t sure yet? What power do they have? “Whether I want kids is a secret I keep from myself — it is the greatest secret I keep from myself.” So writes Sheila Heti in the audaciously titled Motherhood. The book is about Heti’s quest, as she nears forty, to determine once and for all whether she wants to have a child. Mothers is meant to rescue individual women from symbolic abstraction; Heti’s Motherhood is interested only in abstraction. For her, children are a possibility, and thus a projection, a fantasy, and an anxiety. She has no political concerns. There is nothing here about resource wars or the ethics of bringing life onto a violent or dying planet. She simply isn’t sure what she wants, or how to find it out. Her business is a solipsistic existentialism, straight up.

Heti lives in Toronto. In the early 2000s, she published a book of postmodern fairy tales called The Middle Stories and, in 2005, a novel called Ticknor, which was based on a nineteenth-century historian. She then turned her attention closer to home, abandoning made-up characters and invented plots. She collaborated with friends on art projects and, with Misha Glouberman, wrote a book of “conversational philosophy” called The Chairs Are Where the People Go. Her more recent novel, which was published in the United States in 2012, was called How Should a Person Be? James Wood called it “hideously narcissistic,” and the critic Joanna Biggs compared it — without judgment — to The Hills. It was part bildungsroman, part reality show, part pop philosophy, part self-help guide. The characters were based on Heti’s friends, and the book reproduced real conversations. It was part of the early resurgence of “autofiction” that included novels by Ben Lerner and Karl Ove Knausgaard, but it was about an ensemble, a social way of life, rather than a solitary thinker.

Motherhood also calls itself a novel. It’s written in the first person, in a circuitous, confessional style. Like How Should a Person Be?, it is by turns ugly, flip, earnest, and philosophical, but with even less pretense of fictionality. Whether or not everything in it is “real,” it is all personal. It takes up the challenge that the character Sheila laid out in the previous book:

Most people live their entire lives with their clothes on. Then there are those who cannot put them on. . . . They are destined to expose every part of themselves, so the rest of the world can know what it means to be a human.

Some of Motherhood is written according to a coin-flipping method adapted from the I Ching. Two or three heads is a yes; two or three tails, a no. The coins help Heti organize her thoughts and analyze her dreams. She asks them about the story of Jacob wrestling the archangel, which she finds resonant. (“And then I named this wrestling place Motherhood, for here is where I saw God face-to-face, and yet my life was spared.”) Many questions Heti poses to the coins involve her boyfriend, Miles. Miles has a daughter from a previous relationship and does not want another kid. He calls having children a “handicap.” He says that parenthood is “the biggest scam of all time.”

Should I have a child with Miles?

no

Should I have a child at all?

yes

So then I should leave Miles?

no

Should I have an affair with another man while I’m with Miles, and raise the child as Miles’s own, deceiving him about the provenance of that child?

yes

I don’t think that’s a good idea. Are you saying I shouldn’t have a child with Miles because it would be too stressful on the relationship, and on each of us, individually?

yes

It’s possible to imagine another writer — Dorthe Nors, for example — pursuing this business with the coins for a whole book, with great success. But that would be too much of a constraint on Heti, who prefers a baggier mélange of forms. The book is composed mostly of journally passages, divided into short chapters and stand-alone paragraphs, which vary considerably in sagacity and interest. There are also trips to literary festivals, a meeting with a fortune-teller, some family history, and summaries of conversations with friends, many of whom have betrayed the author by having children.

I had always thought my friends and I were moving into the same land together, a childless land where we would just do a million things together forever. I thought our minds and souls were all cast the same way, not that they were waiting for the right moment to jump ship, which is how it feels as they abandon me here.

There is something more here than sour grapes. Heti relies on her friends as material and as collaborators. As they disappear into the inside world of babies, the loss is artistic as well as social. “Living one way is not a criticism of every other way of living” is something she says but doesn’t really believe. Her friends pressure her in subtle or unsubtle ways to have children, sometimes by saying that they are happy, sometimes by saying that they are jealous of everything Heti is accomplishing. The mutual incomprehension of the childless and those with children is, as ever, depressing. There is envy on both sides, and fear, and projection. It is always easier to feel aggrieved and misunderstood than it is to be curious about what life is like for other people. “Libby said that I was a young soul, or must be, still discovering the world — she meant I was not an old enough soul to want to make a baby.” Libby, who must be in line for sainthood, says this on the occasion of introducing her two-month-old baby to Heti. If one of my friends, on meeting my baby, had turned the conversation to herself, I would not have reassured her about the youth of her soul. But I think — I would think this! — that new mothers are entitled to a temporary lack of curiosity about the outside world. They are in a state of primary maternal preoccupation, without which their babies would die.

Motherhood is also an inside world. For all its investment in “reality,” How Should a Person Be? contained a novelistic scaffolding. There were scenes, rising and falling action. Although that book was also about not-doing — the character Sheila agonized over not writing a play — there was plenty of other stuff that Sheila did do, and there were characters who clearly lived outside of Sheila’s head. Motherhood is claustrophobic, like a diary, or a day with a newborn, and shapeless, even inchoate. It exists only to keep existing. Resolution is deferred while the author examines the problem from every side and then one more. “Even if one comes to a definite resolution against having children,” she writes, “hanging over one’s head remains a spectre, the possibility, that a child will come.” But maybe . . . then again . . . It goes on and on, building to a desperate static. She says things like,

Sometimes I’m convinced that a child will add depth to all things — just bring a background of depth and meaning to whatever it is I do. I also think I might have brain cancer. There’s something I can feel in my brain, like a finger pressing down.

These do not seem to be the thoughts of someone who seriously intends to have a baby. Or perhaps they are the thoughts of someone whose desire is so thwarted that she has mounted elaborate intellectual and comic defenses against it. Or perhaps she truly believes that she has brain cancer. We are in uncomfortable waters, and the reviewer is forced to play therapist. If Heti does want a child, what is preventing her — Is it Miles, or her own adolescent notions of freedom? If she doesn’t want a child, why can’t she just get on with not having one? For a while I thought that the book was a pointed social critique, meant to demonstrate the difficulty of living outside convention even for a person who very much wants to. But Heti is not a social critic. Near the end of the book, she is prescribed an antidepressant to treat the debilitating PMS that leaves her “half the month crumpled in tears.”

The drugs seem to be working, that’s all I can say. The drugs really seem to be working. The fear in me, the anxiety, is quelling because of these drugs. . . . What kind of story is it when a person goes down, down, down and down — but instead of breaking through and seeing the truth and ascending, they go down, then they take drugs, and then they go up? I don’t know what kind of story it is.

If you have at all invested in the dilemma of Motherhood, this denouement is a disappointment. But it’s true to the times, and in that respect tells us something about what it means to be human. If you think social problems shouldn’t have pharmacological solutions, take it up with the twenty-first century.

In Little Labors, a book of brief essays written while her daughter (“the puma”) was a baby, Rivka Galchen made a list of twentieth-century women writers who had children and those who didn’t. The survey (which first appeared in this magazine) is more or less as you’d expect. Many (Flannery O’Connor, Elizabeth Bishop, Hannah Arendt) did not have children. A few (Toni Morrison, Alice Munro, Penelope Fitzgerald) did. A couple (Muriel Spark, Doris Lessing) had children and abandoned them. The ones who had children published later in life. Female writers who had children published fewer books than male writers who had children. I’m not sure what to make of it all. Does publishing early make you a better writer? Is writing more books better than writing fewer books? Could the experience of having children make it possible for some people to write, just as it makes it impossible for others? And what about the particulars? Was Arendt so cheery about the possibility of “natality” because she didn’t spend five hours a day walking and bouncing a colicky infant? Would we have Beloved if Morrison didn’t know maternal life from the inside?

My two favorite books about motherhood are Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai and Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation. DeWitt is not a mother; Offill is. The Last Samurai begins in the voice of Sibylla, a thwarted scholar, and is eventually taken over by her son, a prodigy named Ludo who goes off in search of his father. It is dense and filled with information about Japanese film, learning Greek, linguistics, etc. Dept. of Speculation is written in fragments, like poetry. The narrator is an author whose second book stalls after she has a child, and then her husband has an affair. Writing this now, I see that both are about intellectual ambition, and men who are in some way absent or unsatisfactory, and children who are completely ravishing yet totally frustrating, everything and not enough. And both gamble that there is something pedagogical or intellectually stimulating about motherhood — that it is, if nothing else, the material of thought, and not opposed to it.

For Heti, it’s an either-or: books or babies. She’s right if you’re trying to do both at the same moment. Rachel Cusk articulated this in her memoir A Life’s Work, which she was able to write because her husband quit his job, telling friends that he was going to “look after the children while Rachel writes her book about looking after the children.” It’s common for female writers to joke that they would like a wife — someone to cook and clean and type up the manuscripts and massage the ego. (Véra Nabokov is often invoked.) Is this a way of saying that they would really like a mother? Heti would like a girlfriend. Having a boyfriend and a girlfriend would make “everything easier, sweeter, more truthful, and more right.”

She learned that work and motherhood were in competition from her own mother, a doctor who “put all of herself into her work and let our father raise my brother and me. . . . A friend once asked me if my mother was dead.” Lacan said that a symptom takes two generations to form. Heti’s maternal grandmother, Magda, survived Auschwitz, studied law, married a man who didn’t suit her, and was forced to help him sell sweaters in Hungary. She urged her daughter, Heti’s mother, to study hard and move to Canada. When Heti tells her mother that she loves her, her mother says, “I am surprised you love me, when I neglected you so much.”

I asked her if motherhood had been the most important part of her life, and she blushed and said, No — at the very same moment that I interrupted her and said, You don’t have to answer. I was there.

In Mothers, Rose quotes Melanie Klein: “Even the most loving mother cannot satisfy the infant’s most powerful emotional needs.” Or maybe the point is that Heti got what she needed after all. “I also am imitating what my mother has done,” Heti says of choosing Motherhood over motherhood. “I do as my mother did, and for the same reasons; we work to give our mother’s life meaning in ways we can’t understand.” The book ends, shamelessly, shockingly, with an email she receives from her mother, who has read the finished draft. “Subject line: It’s magical!” She has made her mother proud. What makes Heti’s mother happiest is that her own mother has been memorialized by her daughter: “You never knew her, and you are the one who will make her alive forever.” Heti and her mother are both daughters. This is what binds them. “Thank you, Sweetheart,” Heti’s mother writes. “I love you very much.”

Could anything be more embarrassing than this naked desire, into middle age, to win the approval of one’s mother, and the need to demonstrate in public that one did? Could anything be more female, more intimate, and less worthy of being made the subject of a novel — and conversely, could anything be more urgent? Heti has done here what Rose says mothers always do: bring shameful human debris into view. She has done it by writing for and about her mother. Her book contains hate but is an act of love. What readers think hardly matters, since the ideal reader has already registered her approval. The book puts itself beyond reproach, which makes it different from motherhood: in real life, mothers are always open to criticism.

Like other recent books about motherhood, including Little Labors, Dept. of Speculation, and Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, Motherhood is written in discontinuous sections. But the meaning of the fragmentation is different in each book. Heti writes in abbreviated passages not because she can get through only a small thought before she is interrupted by a small child. She is constantly beginning again because she is afraid to end. She is a fretting Scheherazade, telling stories to wait out her reproductive years.

I know the longer I work on this book, the less likely it is that I will have a child. Maybe this is why I’m writing it — to get myself to the other shore, childless and alone. This book is a prophylactic.

We might call it a waste of time. Is there a way to say that so that it doesn’t sound like a dig? Anxiety fills up what empty time she has, but still she wants more. “I want to take up as much space as I can in time, stretch out and stroll with nowhere to go, and give myself the largest parcels of time in which to do nothing.” The world has other ideas. She makes a list of all the things a woman is expected to do between the ages of fourteen and forty:

Find a man, make babies, start and accelerate her career, avoid diseases, and collect enough money in a private account so that her husband can’t gamble their life savings away.

This list is a little easy, especially for Heti, who is supposed to be interested in how a person should be, not what the world thinks a person should be. But the longer we live the more we seek the old comforts, and this is one reason that people have kids. Motherhood is attuned to the drumbeat of time. It knows that menstruation is a metronome. Every month, there it is, another egg from the stash flushed down the drain. (This torments women trying to avoid pregnancy and those trying to get pregnant alike.) Time works differently after you have a child. What was once a very steady beat suddenly moves at crazy, uneven speeds. Children fill up time that you didn’t know was empty. They are clocks with all the gears on display; you watch the time pass in them. (A woman who is breastfeeding is also a clock, with a timer set for every two to four hours.) You look at the child and think how nice it would be to freeze him in place, but you would die of boredom if he didn’t change.

Authors talk of ideas “gestating,” of “giving birth” to their books, of “the final push” before a manuscript is due — but the relationship is less commonly articulated the other way. If writing is like motherhood, is motherhood like writing? A child is not a draft. You cannot delete and start again. But there are some rhythms the two tasks share. Both are arts of attention. And in both, time is experienced as an all-consuming present. It is impossible to really remember anything outside the current moment, possible to spend a day writing and a day with a child and end both with no idea what happened and with nothing to show for it. Heti writes about “longing for a holy completeness,” but that is a fantasy of sex or pregnancy, not motherhood. Motherhood, like writing, is a state of incompletion. Something is always missing. And it never ends.

To have a child is to be, in the best scenario, cut off from the root of the question of whether or not to have a child. The experience is so utterly transformative that the person evaluating the decision is a different version of the person who made it. That is why it’s exciting. It remakes the world. Motherhood offers something else — loyalty to the version of the person Heti is now. She writes, “Raising children is the opposite of everything I long for, the opposite of everything I know how to do, and all the things I enjoy,” as if what one longs for can never change. She refuses to become someone else, someone who takes an interest in “those simple joys, those deeply private accomplishments” of child-rearing. Rose shows us that motherhood is neither simple nor private. But Heti’s fantasy of motherhood is not the point. The point is that she wants to extend the present version of herself into the future. What is that but a way of stopping time? Who wouldn’t want that power?

I think of Dept. of Speculation:

I would give it up for her, everything, the hours alone, the radiant book, the postage stamp in my likeness, but only if she would consent to lie quietly with me until she is eighteen. If she would lie quietly with me, if I could bury my face in her hair, yes, then yes, uncle.

My mother babysat while I wrote this article.