It has become something of a commonplace to say that Mike Pence belongs to another era. He is a politician whom the New York Times has called a “throwback,” a “conservative proudly out of sync with his times,” and a “dangerous anachronism,” a man whose social policies and outspoken Christian faith are so redolent of the previous century’s culture wars that he appeared to have no future until, in the words of one journalist, he was plucked “off the political garbage heap” by Donald Trump and given new life. Pence’s rise to the vice presidency was not merely a personal advancement; it marked the return of religion and ideology to American politics at a time when the titles of political analyses were proclaiming the Twilight of Social Conservatism (2015) and the End of White Christian America (2016). It revealed the furious persistence of the religious right, an entity whose final demise was for so long considered imminent that even as white evangelicals came out in droves to support the Trump-Pence ticket, their enthusiasm was dismissed, in the Washington Post, as the movement’s “last spastic breath.”

But Pence is a curious kind of Christian politician. He is more fixated on theological arcana than on the Bible’s greatest hits (the Ten Commandments, the beatitudes). His faith is not that of Mike Huckabee, say, whose folksy Christian nationalism is reflected in the title of his book God, Guns, Grits, and Gravy; nor is it the humble self-help Methodism to which George W. Bush once deferred (at least in his early years, before his faith was hijacked by a geopolitical crusade), speaking of Jesus as the guy who had “changed my heart.” Indeed, the most peculiar thing about Pence’s Christianity is how rarely he mentions the teachings of Christ. Despite his fluency with Scripture, he seldom quotes the Gospels. He speaks fondly not just of the Good Book but also of the Old Book, by which he usually means the Hebrew Bible, and it is this earlier testament that he draws from in his speeches, often with the preface that it contains “ancient truths” that are “as true today as they were in millennia past.”

Pence does live in the past, a past far more ancient than anyone has assumed. He speaks of the Old Testament as familiar terrain and regards its covenants as deeply relevant to evangelicals. The God of these stories is not the familiar, tranquilized Jesus of hymns and dashboard figurines but the more forbidding Yahweh who disciplines and delivers the nation of Israel. The God of Mike Pence is the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, a God who sets up kings and tears them down, who raises the poor from the dust and lifts up the needy, who pulls candidates off the political garbage heap and allows them to rule with princes. He is a God who keeps his promises, and the promise, throughout the ages, has always been the same: that the Chosen People will be restored to their rightful home.

The biblical concept of exile—a banishment followed by a return to the homeland—has lately acquired special meaning for evangelicals. The term inundated Christian discourse in the United States following the failure of Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), which Pence, then the governor, signed in 2015, soon after a judge struck down the state’s ban on same-sex marriage. The bill, which would have allowed businesspeople such as florists and caterers to refuse to serve gay clients, inspired a national boycott and culminated in a disastrous appearance on George Stephanopoulos’s This Week, in which Pence evaded question after question and stammered about open-mindedness being a two-way street. “From people who preach tolerance every day,” he said, “we have been under an avalanche of intolerance.” Pence was forced to neuter the bill, and the ordeal soon fell out of the news cycle.

But for conservative Christians, who had long seen themselves as at war with the culture, the backlash was a wake-up call. Rod Dreher, an Eastern Orthodox writer for The American Conservative, claims this was the moment he realized that American believers were “living in a new country.” In late June 2015, the Obergefell v. Hodges decision legalized gay marriage in all fifty states, and Dreher proclaimed in Time magazine that the culture wars were officially over. Progressive views on marriage and sexuality had become consensus, and Christians would now be targeted as dissenters, their beliefs classed as hate speech. “We are going to have to learn how to live as exiles in our own country,” he wrote. Russell Moore of the Southern Baptist Convention lamented Obergefell but offered a brighter perspective, calling on Christians to “joyfully march toward Zion” as “strangers and exiles in American culture.” Soon, cries of exile (or #exile, per Twitter) could be heard all over Christendom.

But for conservative Christians, who had long seen themselves as at war with the culture, the backlash was a wake-up call. Rod Dreher, an Eastern Orthodox writer for The American Conservative, claims this was the moment he realized that American believers were “living in a new country.” In late June 2015, the Obergefell v. Hodges decision legalized gay marriage in all fifty states, and Dreher proclaimed in Time magazine that the culture wars were officially over. Progressive views on marriage and sexuality had become consensus, and Christians would now be targeted as dissenters, their beliefs classed as hate speech. “We are going to have to learn how to live as exiles in our own country,” he wrote. Russell Moore of the Southern Baptist Convention lamented Obergefell but offered a brighter perspective, calling on Christians to “joyfully march toward Zion” as “strangers and exiles in American culture.” Soon, cries of exile (or #exile, per Twitter) could be heard all over Christendom.

I left the faith more than a decade ago but remain connected to it, tangentially, through a large born-again family and an abiding anthropological curiosity, so these things tend to reach me. I knew that while exile appeared to be a fluid metaphor—a way to talk about religious liberties and political impotence—it also had a specific historic referent: the period the Jews spent in Babylonian captivity. Accounts of the exile are scattered throughout the books of the Old Testament, though the story generally begins in 587 bc, when Nebuchadnezzar’s army razed Jerusalem and burned the Temple to the ground. The Israelites were deported to Babylon, where they remained for seventy years, lamenting the ruin of Zion and praying for deliverance. In these stories, the empire is led by a series of despotic rulers—Nebuchadnezzar, Nabonidus, Belshazzar—who seem to find sadistic pleasure in forcing the Jews to renounce their God and, when they refuse, throwing them to wild animals or into the fiery furnace. When I was studying theology at Moody Bible Institute, during the Bush years, none of my fellow students were particularly drawn to these books. But Christians have often returned to them during times of persecution, and apparently they had become newly relevant for believers who saw themselves as a religious minority in a hostile pagan empire—a people who had long mistaken Washington for Jerusalem, and for whom the image of the White House lit up in a rainbow was a defeat as final as the desecration of the Temple.

Of course, for anyone familiar with evangelical rhetoric, it is obvious that “exile” is not a white flag but a revamped strategy. The Babylonian exile, after all, was temporary. All the lamentations were ultimately about deliverance, and that deliverance came in the form of a strongman: in 539 bc, Cyrus the Great, the king of Persia, conquered Babylon and allowed the Jews to return to Jerusalem.

Once Donald Trump became a serious contender for the Republican Party’s presidential nomination in early 2016, some Christians saw him as the instrument of deliverance. This idea came primarily from the theological fringe that Trump courted: televangelists, Pentecostals, health-and-wealth hucksters. It came from men such as Lance Wallnau, an evangelical public speaker who met with Trump during his campaign and, since 2015, had been writing articles that likened the candidate to Cyrus. Throughout history, Wallnau argued, God had used pagan leaders to enact his will and protect his people. Just as Cyrus was a powerful leader anointed by Yahweh to end the exile, so Trump was “a wrecking ball to the spirit of political correctness.” Wallnau eventually published his theory in a book titled God’s Chaos Candidate (2016). Just before the election, it reached number nineteen on Amazon’s bestseller list, and others have continued to make the comparison. In March 2018, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu visited the United States and joined the evangelical chorus. “The Jewish people have a long memory,” he told Trump in the Oval Office. They remember Cyrus. “Twenty-five hundred years ago, he proclaimed that the Jewish exiles in Babylon could come back and rebuild our temple in Jerusalem.”

Plenty of Christians cautioned against this narrative—most notably Moore, in the Washington Post. He and Dreher represent a more orthodox core who remained skeptical of Trump and believed his presidency would be a continuation of pagan rule. (Dreher has condemned Christians who want to “Make Babylon Great Again.”) Alan Snyder, a Christian historian, wrote on his blog, “There’s another biblical figure who didn’t acknowledge God, yet God used him to carry out a purpose.” He was referring to Nebuchadnezzar, who is not remembered kindly in the Old Testament. In one story, he decrees the construction of a gold statue of himself and orders his subjects to bow down and worship it. In another, his counselors fail to adequately interpret a dream, and he threatens to kill off his entire court. He is suspicious of his advisers, tortured by nightmares of his own demise; eventually, he loses his mind. For Christians who were anti-Trump, the parallels were obvious, and ominous: “His purpose?” Snyder wrote of Nebuchadnezzar. “To destroy Jerusalem and take the people into captivity.”

Plenty of Christians cautioned against this narrative—most notably Moore, in the Washington Post. He and Dreher represent a more orthodox core who remained skeptical of Trump and believed his presidency would be a continuation of pagan rule. (Dreher has condemned Christians who want to “Make Babylon Great Again.”) Alan Snyder, a Christian historian, wrote on his blog, “There’s another biblical figure who didn’t acknowledge God, yet God used him to carry out a purpose.” He was referring to Nebuchadnezzar, who is not remembered kindly in the Old Testament. In one story, he decrees the construction of a gold statue of himself and orders his subjects to bow down and worship it. In another, his counselors fail to adequately interpret a dream, and he threatens to kill off his entire court. He is suspicious of his advisers, tortured by nightmares of his own demise; eventually, he loses his mind. For Christians who were anti-Trump, the parallels were obvious, and ominous: “His purpose?” Snyder wrote of Nebuchadnezzar. “To destroy Jerusalem and take the people into captivity.”

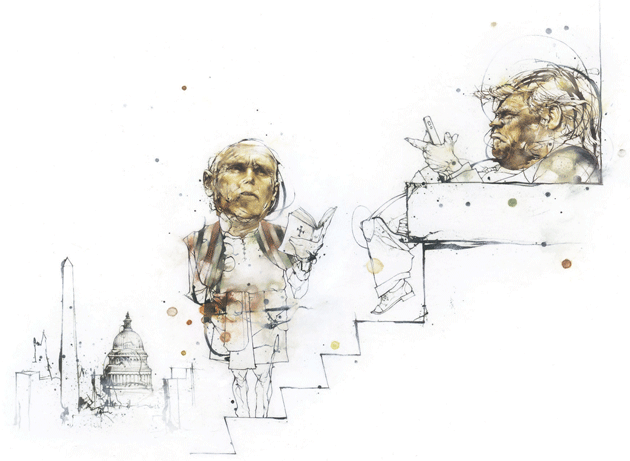

How did Pence fit into these narratives? Soon after the Republican National Convention that summer, a friend asked me about the likelihood of Pence solidifying the evangelical vote. (As a former believer, I am sometimes considered an authority on such things.) I remarked offhandedly that Christians regarded Pence as an intercessor, one who would temper the president’s moral excesses just as Christ intervened two thousand years ago to mollify the reckless whims of Yahweh.

I’d forgotten that there is a more apt analogy in the Old Testament. One of the foremost heroes of the exile stories is Daniel, an Israelite who serves in Nebuchadnezzar’s palace. Daniel manages to preserve his Jewish identity, refusing the king’s food and wine and continuing to pray to his God, sometimes in secret. When Daniel correctly interprets one of the king’s dreams, he is promoted to chief counselor, a position he uses to establish protections for the Jews and secure appointments for his Hebrew friends. He also ends up serving as the king’s spiritual adviser, encouraging him to turn from idolatry and worship Yahweh, the one true god. Still, despite earning royal favor, Daniel frequently comes into conflict with the king’s temper and the paganism of Babylon. When he refuses to obey a decree that would prohibit him from praying to his God, he is thrown into the lion’s den.

These stories have long been read by Christians as a handbook in civil disobedience. (Martin Luther King Jr. invoked the Book of Daniel in “Letter from Birmingham Jail” to defend the virtue of protesting without a permit.) But the story of Daniel also suggests that godly people can negotiate power by influencing leaders whose values differ vastly from their own. At the dawn of the Trump era, the lesson contemporary evangelicals gleaned from the story of Daniel was that God’s people can survive in exile—even under the fist of a despotic ruler—so long as one of their own tribe advocates on their behalf in the corridors of power.

College Park Church, the congregation that Mike Pence attended during his governorship, sits in northern Indianapolis, among golf courses and midpriced chain hotels. The neighborhood is on the cusp of the suburbs, many of which are named, incidentally, after the landscape of the Old Testament: Lebanon, Carmel, Zionsville. As soon as I entered the foyer, I recognized it as the kind of church I grew up in: large and contemporary but without the gaudy trappings of a megachurch; doctrinally orthodox but passionate about social welfare. It’s the kind of church that people like my parents would call “theologically sound,” which is a way of saying that the pastors went to the right schools, that worship avoids the charismatic theater of snakes and spirit slaying, that the sermons never descend into partisan shilling. It is not, in short, the kind of church that is, or ever was, uniformly gung ho about Trump.

Pence took a somewhat circuitous route to evangelicalism. He was raised Irish Catholic and converted in college, when he realized, at a Christian music festival, that “what happened on the cross, in some small measure, actually happened for me.” He avoided explicitly linking his beliefs to his politics during his early public career, but his faith deepened after he lost his second congressional race, in 1990.

Around the same time, he began regularly attending an evangelical megachurch with his family and joined the board of the Indiana Family Institute, a far-right group that was antigay and antiabortion. By the time he campaigned again for Congress, in 2000, his faith was at the forefront of his platform, which zeroed in on issues such as abortion, school prayer, and support for Israel. When Pence arrived in Washington as a representative from Indiana, one staffer claimed that he would cite specific verses to justify policy decisions. “These have stood the test of time,” Pence said of the Scriptures. “They have eternal value.”

I was curious about Pence’s spiritual heritage and how the Bible teaching he’d received had inflected his political worldview. But the more immediate reason I’d come to Indianapolis was that College Park was wrapping up an eighteen-month sermon cycle on exile. In the sanctuary, a dimmed auditorium with stadium seating, a member of the church pointed to the spot a few rows behind me where Pence used to sit on Sunday mornings with his wife, Karen, taking copious notes while dressed in a windbreaker bearing the state seal. The last time the congregant I was speaking to had spotted Pence in church was shortly after he joined Trump on the Republican ticket. He was accompanied by two Secret Service agents and sneaked out before the benediction.

At that time, College Park’s lead pastor, Mark Vroegop, was in the middle of the exile series. From early 2016 until the middle of 2017, he walked his congregation through Lamentations and Daniel, then on to a series called This Exiled Life. These sermons often drew on Babylon stories to explore ethical dilemmas that his flock might encounter in the world of boardrooms and watercoolers: Your boss hands down a new policy that your faith precludes you from fulfilling. Your co-workers don’t know you’re a Christian. Do you share your views or fly under the radar? “For some of you,” Vroegop said, “the island of marginal Christianity is shrinking, and you’re going to have to think very carefully… ‘When do I draw a line?’”

Vroegop is a tall, fortysomething man with a commanding voice, the kind of pastor who seems equally suited to heading corporate leadership seminars. I met him one day in his office, a small, sunny room lined with hundreds of theology books, alphabetized by author. He gave me one of them—Timothy Keller’s Making Sense of God—when I mentioned that I’d left the faith in my early twenties. He told me the sermons on exile grew out of conversations he had with his congregants following RFRA and the Obergefell decision. “I would encounter believers who, frankly, just had this sense of panic about them,” he said. Many of them, particularly those who worked in HR or higher education, were confronting new office protocols about gender and sexuality, and he realized that the Old Testament might be instructive. “I think in the Babylonian exile, there was this reality of, look, we’re going to be here for a while, we’ve got to figure out how to be Jewish and to honor our God in the midst of a culture that is just godless,” he said. “And there were folks who figured out how to do that. You know, Daniel gets to a very high level of government.”

During the summer of 2016, Vroegop preached on the Book of Daniel, describing Nebuchadnezzar as “an angry, irrational king” and likening Daniel’s position to “the vice presidency, if you will, of the country.” The sermons focused on the delicate balancing act that Daniel performs. While he strives to stay on the king’s good side, he also tells him difficult truths and urges him to keep his promises to the exiles. “Somehow,” Vroegop said in one sermon, “Daniel had figured out how to be faithful to God while serving the Babylonian Empire faithfully as well.” I pointed out to Vroegop what seemed obvious to me—that the sermons were an allegory about Pence and Trump. Vroegop listened patiently while I drew these parallels but insisted that Pence had not been on his mind. At the time, he said, Pence wasn’t even being considered for the ticket. (Vroegop preached his final Daniel sermon on June 26; Pence was announced as running mate on July 15.)

Vroegop has a long-standing policy against speaking about Pence to the press, but others have floated the idea of him as a Daniel-like figure, including some Indianapolis Christians who know him personally. Gary Varvel, a columnist and political cartoonist who has been friends with the vice president since the Nineties, told me he’d thought of Daniel as soon as Pence was announced as Trump’s running mate. “I would be surprised if he didn’t consider this as a divine appointment, so to speak,” he said.

It’s clear that Pence sees himself as the defender of an imperiled religious minority. During the uproar after the RFRA, he did not refer to the country’s supposed religious foundations, nor did he appeal to Christian values as an all-purpose national ethic. Instead, drawing on the vocabulary of identity politics, he declared that the law would “empower” religious people whose liberties were being “infringed upon.” Pence had tapped into the language of exile, and by the time he joined Trump’s campaign, he had become fluent, promising James Dobson that a Trump-Pence Administration would be “dedicated to preserving the liberties of our people, including the freedom of religion that’s enshrined in our Bill of Rights.”

For Christians who were immersed in these ancient myths, Pence made for a familiar figure, a member of the tribe who would represent them in the court of a pagan empire, a man who could encourage an unpredictable king to keep his promises. A former adviser quoted in GQ claims that Pence joined the ticket after he was reminded that “proximity to people who are off the path allows you to help them get on the path.”

The stories of exile helped evangelicals come around to the idea of a Trump presidency. Since Election Day, these same stories have been marshaled to incite loyalty to Trump—particularly within the administration itself. Ralph Drollinger, a former NBA player and the founder of Capitol Ministries, leads Bible studies that take place weekly in both the House and the Senate. During the Obama Administration, Pence was one of the group’s sponsors, along with Michele Bachmann, Tom Price, and Mike Pompeo.

A few weeks after the election, on November 28, Drollinger held a reception where he distributed Bible-study notes on the stories of Daniel, Joseph, and Mordecai. He declined my request for an interview, but Capitol Ministries sent me the notes, “Maintaining Biblical Attitudes with New Political Leadership,” which were clearly designed to quell internal fractiousness over the incoming president. (Drollinger was an outspoken Trump supporter throughout the campaign.)

The document begins by acknowledging that many people in office had been vocal about their displeasure at Trump’s election. Drollinger aimed to demonstrate the “exemplary behavior” of Old Testament figures like Daniel, “who stood their ground for God, and yet maintained respect for those in authority with whom they did not agree.” What distinguished Daniel, he wrote, was his “loyal service” to and “manifest respect” for the king. Even though he served a foreigner who did not recognize his religion, Daniel made himself useful and encouraged the ruler to follow Scriptural commands. Drollinger then explicitly likened Pence to Daniel. “For years, Governor Pence has embodied these aforesaid biblical characteristics, and God has elevated him to the number-two position in our government.”

Pence has certainly fulfilled this prescription of loyalty. During the first full Cabinet meeting, the vice president declared that working for Trump was “the greatest privilege of my life,” provoking a chain of obsequious echoes from the other attendees. His unwavering devotion to his leader has earned him the endearment “sycophant in chief.” He has declined to publicly disagree with the president, even in the crucible of his worst political traumas. When Trump refused to condemn white supremacists in Charlottesville, Virginia, for example, Pence not only defended him but did so in the soothing tones of a spiritual adviser. “I know this president,” he told Matt Lauer. “I know his heart.”

And yet it’s difficult to overstate how far Drollinger’s exegesis—which imagines Daniel as a deferential subject—strays from Christian orthodoxy, which traditionally celebrates him as a righteous dissenter. Pence’s shows of deference reek of political strategy; his tenure so far reflects the more cynical implication of Drollinger’s lesson: that the most expedient way to accomplish a religious agenda is to perform fealty to the king while working behind the scenes on behalf of your own people. Pence was instrumental in the choice of Neil Gorsuch for the Supreme Court and is believed to have influenced many Cabinet appointments, including those of Betsy DeVos, Tom Price, and Mike Pompeo—a cohort that, in the words of the writer Jeff Sharlet, may create “the most fundamentalist Cabinet in history.” Christian lobbyists, along with Pence, seemed to play an important role in persuading Trump last December to declare that the United States would recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. In his address to the Knesset the next month, Pence explicitly tied American history to the Jewish exile narratives. “In the story of the Jews,” he said, “we’ve always seen the story of America.”

Although Pence has denied that he has higher ambitions, political commentators haven’t ruled out the prospect of a Pence presidency. Last year, he launched the Great America Committee, the first PAC started by a sitting vice president. This development, coupled with reports that he was hosting dinners for wealthy Republican donors at his official residence, led to rumors that he might be running a shadow campaign. Regardless of whether Pence ends up running in 2020—or whether some fateful event promotes him to commander in chief—it appears he is planning a political future independent of Trump. This prospect causes no shortage of anxiety on the left. Sarah Jones remarked in The New Republic that if Pence had his way, America would become like Gilead, the dystopian state of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, where women are considered property and “gender traitors” are publicly executed.

But one needn’t look to fiction to conjure the kind of theocracy that Pence might prefer. It’s right there in the Bible. After the Israelites were freed from exile, they returned to Jerusalem, rebuilt the Temple, and constructed a wall around the city. Under the leadership of a high priest, Judah became a theological state operating according to the Law of Moses, which outlined an inflexible code of hygiene and diet and forbade divorce and homosexuality. Some Old Testament sources dramatize this era as a revival of religious and ethnic purity, a period in which Jerusalem was systematically purged of foreign influences; in the Book of Ezra, non-Jews were persecuted, and men were forced to give up their foreign wives and children.

Pence himself has alluded to this return narrative in his speeches and public appearances. The verse he chose for his swearing-in as vice president—2 Chronicles 7:14—reiterates the conditions of God’s covenant with Israel and the promise of a restored theocratic homeland. American evangelicals see themselves as the inheritors of these covenants, which is something commentators miss when they predict, again and again, the decline of the religious right. Such assumptions rest on the modern, liberal notion that history is an endless arc of progress and that religion, like all medieval holdovers, will slowly vanish from the public sphere. But evangelicals themselves regard history as the Old Testament authors do, as a cycle of captivity, deliverance, and restoration, a process that is sometimes propelled by unlikely forces—pagan strongmen, despotic kings. This narrative lies deep in the DNA of American evangelicalism and is one of the reasons it has remained such a nimble and adaptive component of the Republican Party.

One of Pence’s favorite Bible verses is Jeremiah 29:11: “For I know the plans I have for you … plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.” The verse, which currently hangs above the mantel of the vice president’s residence in Washington, contains God’s promise to free the Jews after their captivity in Babylon. In a later verse, God vows, “I will gather you from all the nations and places where I have banished you … and will bring you back to the place from which I carried you into exile.”

Kingdoms rise and kingdoms fall. After Cyrus conquered Babylon, the region remained within the Persian Empire until 331 bc, when it fell to the Greeks under Alexander the Great. The Romans came next, then the Arab Islamic empires and the Ottomans. Today, several of the countries that once made up the Neo-Babylonian Empire—including Syria and Iraq—are blighted by war and political chaos as vicious as that of the biblical era. Since the beginning of the civil war in Syria, 11 million people have fled their homes. Many are living in exile across the Middle East, while others have sought refuge in Europe or the United States.

In November 2015, days after the Paris terrorist attacks, Mike Pence, as governor, issued a directive suspending the resettlement of Syrian refugees in Indiana. He claimed this was a security measure, arguing that Syrian refugees had carried out the attacks. (The culprits were in fact believed to be EU citizens, though there were reports that one had posed as a refugee.) It is difficult to ignore a central irony: the rhetoric of exile had cleared the way for an administration that is waging war on actual political exiles.

During our conversation, Vroegop had told me that Indianapolis is home to a sizable refugee community. This was something he mentioned to me in passing while describing his church’s outreach programs, but it stuck with me. While I was at College Park, nobody said anything nativist or xenophobic; Vroegop himself spoke of the “growing, beautiful diversity” of his congregation. So before I left town, I visited Exodus Refugee Immigration, the largest resettlement agency in the state. After Pence’s 2015 Syrian ban, Exodus partnered with the American Civil Liberties Union to file a lawsuit against the governor. Eventually, an appeals court ruled that Pence’s directive amounted to “discrimination on the basis of nationality.” Cole Varga, the executive director of Exodus, told me that last year had been “fairly chaotic,” which struck me as a morbid understatement. Because of the Trump Administration’s travel bans, Exodus had received roughly half the arrivals they had expected, and their federal funding had been drastically cut; that February, he’d let go more than a third of his staff.

Varga introduced me to Shereen, a Syrian exile whose journey to the United States was almost derailed by the travel ban in January 2017. (Shereen asked that her last name not be used.) She, her husband, and her son had been living in Turkey as refugees for three years when their file was finally referred to the United States. They were packed and ready to go when they got the news that their flight had been canceled. “We thought we would never get the chance to come,” Shereen told me. “For my husband and I, it’s not a problem. We can live anywhere, we can work. We can start all over. But we were more concerned for my son…. We wanted the opportunity to come to the United States to provide a life for him.”

Her son, Jowan, was in the Exodus office with her. He was diagnosed with cerebral palsy at birth and was in a wheelchair. Shereen explained that from the time they fled Aleppo in 2013, Jowan hadn’t been able to attend school or receive physical therapy. When a federal appeals court put the ban on hold, she and her family came to the United States, and Jowan is now enrolled in school and receiving treatment. But they are among the lucky ones. Varga told me that he spends a lot of time thinking about all the people who “should be here right now.”

Throughout our conversation, I kept thinking of a speech Pence gave a few months earlier at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, at an event for persecuted Christians. He argued, as he has elsewhere, that Christians are called to live in exile, “outside the city gate,” barred from the security of the polis. Even though this administration has returned evangelicals to power, Pence still refers to Christians as an endangered minority. “No people of faith today face greater hostility or hatred than followers of Christ,” he said in the speech. His sympathy for exiles, it seems, doesn’t extend to non-Christians. Pence pays lip service to the religious liberties of “all people of all faiths,” but he has consistently defended Trump’s measures to prevent Muslims from entering the United States. When Trump signed the travel ban that would have prevented Shereen and her family from immigrating, Pence stood by his side.

Though the vice president likes to draw from the Old Testament’s promises of redemption, these texts are undergirded by a brutal moral calculus that is difficult to reconcile with the teachings of Christ. Israel always gets what it deserves—punishment or deliverance—and yet so many others are the collateral damage of that cycle. There are the enemies of Israel, who are slain without mercy. And there are the countless foreign tribes who get caught in the crosshairs—groups who are settled on territories God intends for Judah, or people whose religion poses a threat to Jewish purity. Their demise appears in the margins of these stories, often in a single sentence: They burned all the towns where the Midianites had settled, as well as all their camps. I remember coming across these passages when I was in Bible school, struggling with the first shadows of doubt, trying and failing to understand why so many people had to suffer for one group’s redemption—why this ongoing drama between the elect and their God had to come at such a terrible cost.