As he approached his death in 1987, the photographer Peter Hujar was all but unknown, with a murky reputation and a tiny, if elite, cult following. Slowly circling down what was then the hopeless spiral of AIDS, Peter had ceaselessly debated one decision, which he reached only with difficulty, and only when the end drew near. He was in a hospital bed when he made his will that summer, naming me the executor of his entire artistic estate—and also its sole owner.

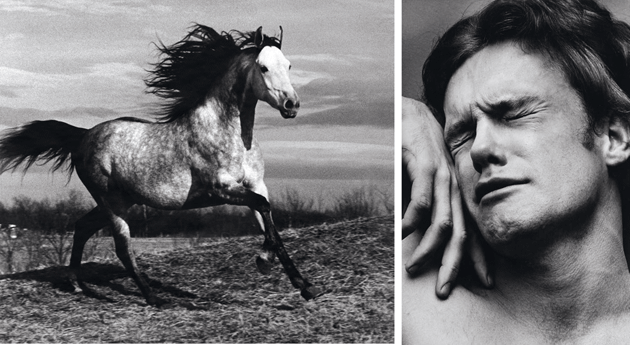

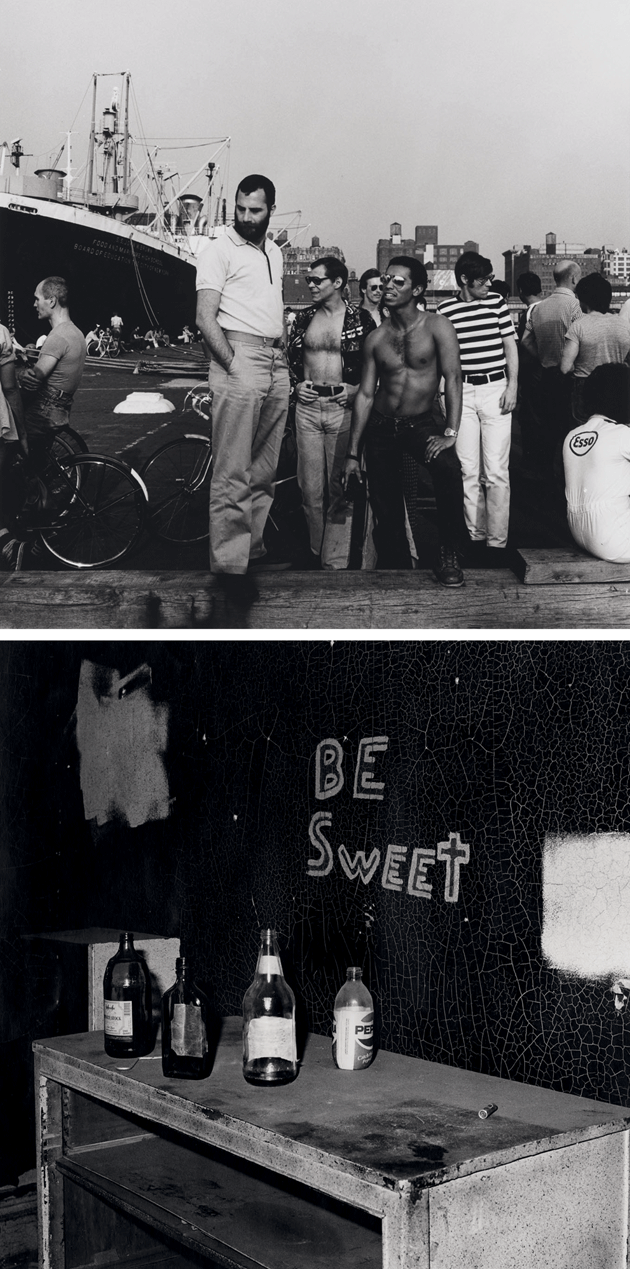

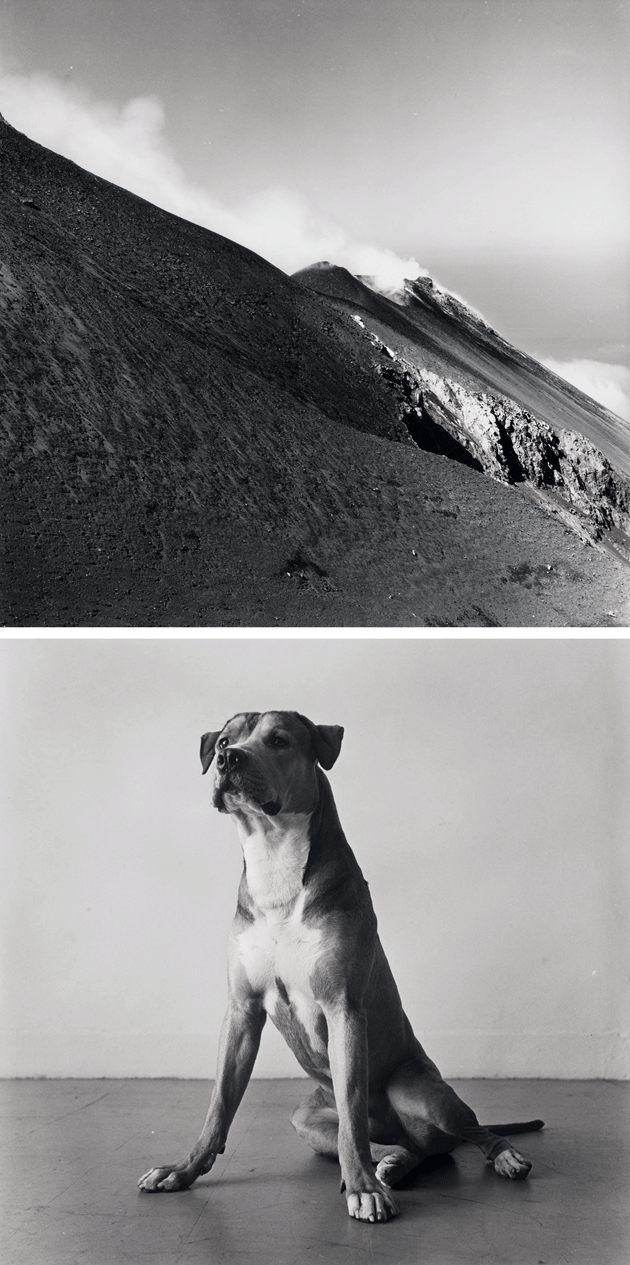

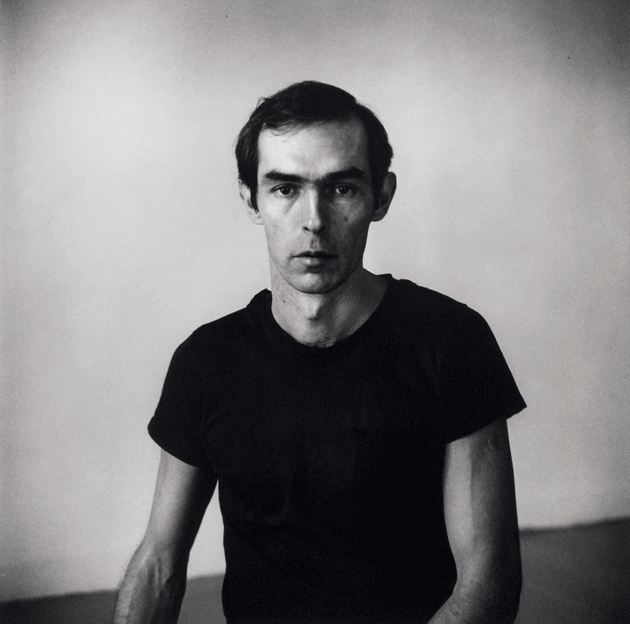

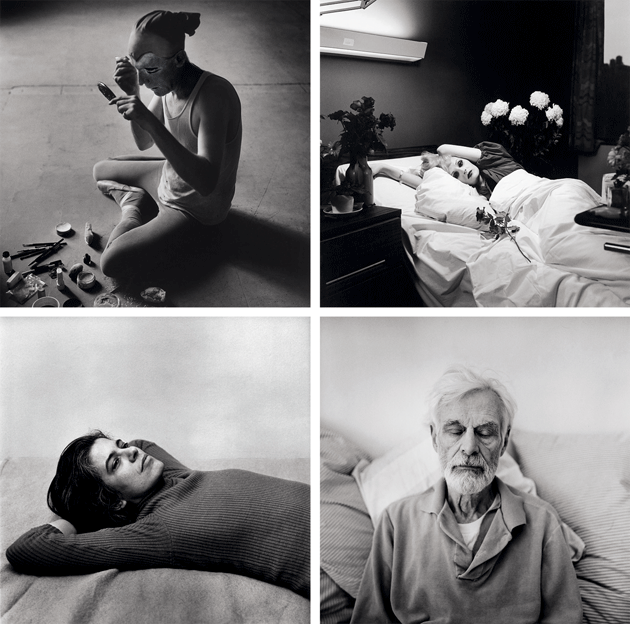

“Boy on Raft,” 1978. All photographs by Peter Hujar © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York City/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. Hujar’s work is on view at the Morgan Library and Museum, in New York City, through May 20, and his monograph, Peter Hujar: Speed of Life, was published last year by Aperture.

The move transformed my life and induced a seething fury in lots of decent people. I can see why. Peter did not make me his heir for any of the usual reasons. I was a good and trusted friend, but he had scads of those. I was not the first person he considered for the job, nor was I the most qualified. In fact, I was a rank amateur, and my understanding of his art was limited. I knew his photographs were stunning, often upsetting, unpredictably beautiful, distinctively his. I also knew they were underrated and neglected. But I did not then really grasp his achievement.

Yet he chose me. By making that choice, he bequeathed to me a mission. Success—serious success—had always teased and eluded us both, and we were constantly debating why. What were we doing wrong? What was the secret? Because of our countless intimate talks on this thorny subject, I instantly knew why he had chosen me. Peter wanted me to pull his work out of the shadows where it had both flourished and languished: he wanted the reputation and the place in history we both knew he deserved. My mission, in other words, was to usher his art into posthumous fame.

The grand archetype for posthumous fame in art is, of course, the rescue of Vincent van Gogh’s work by his bourgeois younger brother, Theo (and Theo’s wife, Johanna). When he died, Van Gogh had a small circle of admirers, and had sold at least two paintings. None of that was enough, however, to secure his legacy. Shepherding his work out of obscurity took decades of hard work, oxlike persistence, strong allies, strategic smarts, unshakable faith, and (not least) good luck.

Of course, any rescue depends first and foremost on the quality of the art itself. The work the dead leave behind can’t be merely good or even very good. It must be magnificent—anything short of that and the resurrection will fail. And even then, Van Gogh’s paintings and drawings could have been left to rot in some attic in Amsterdam or a reeking stable in Arles. Someone had to save them. Someone had to find a public for them. Someone had to keep them from the inevitable oblivion that swallows up almost all human effort, whether mediocre, magnificent, or somewhere in between.

Why did Peter choose me? I was his Theo, his bourgeois brother.

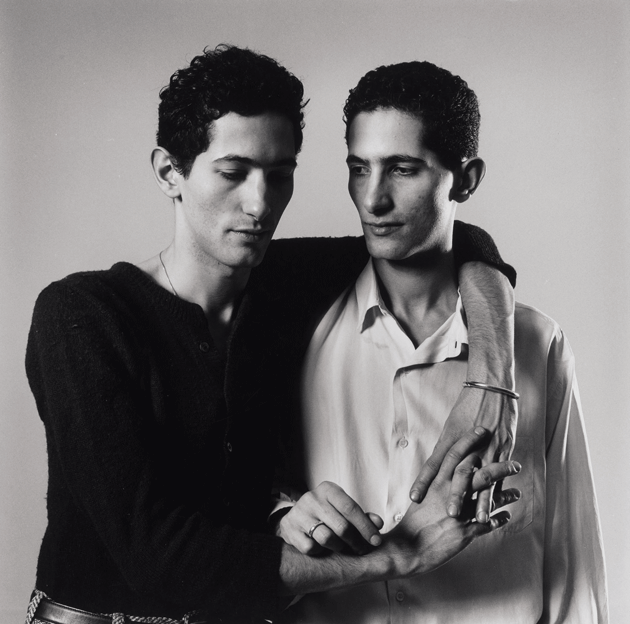

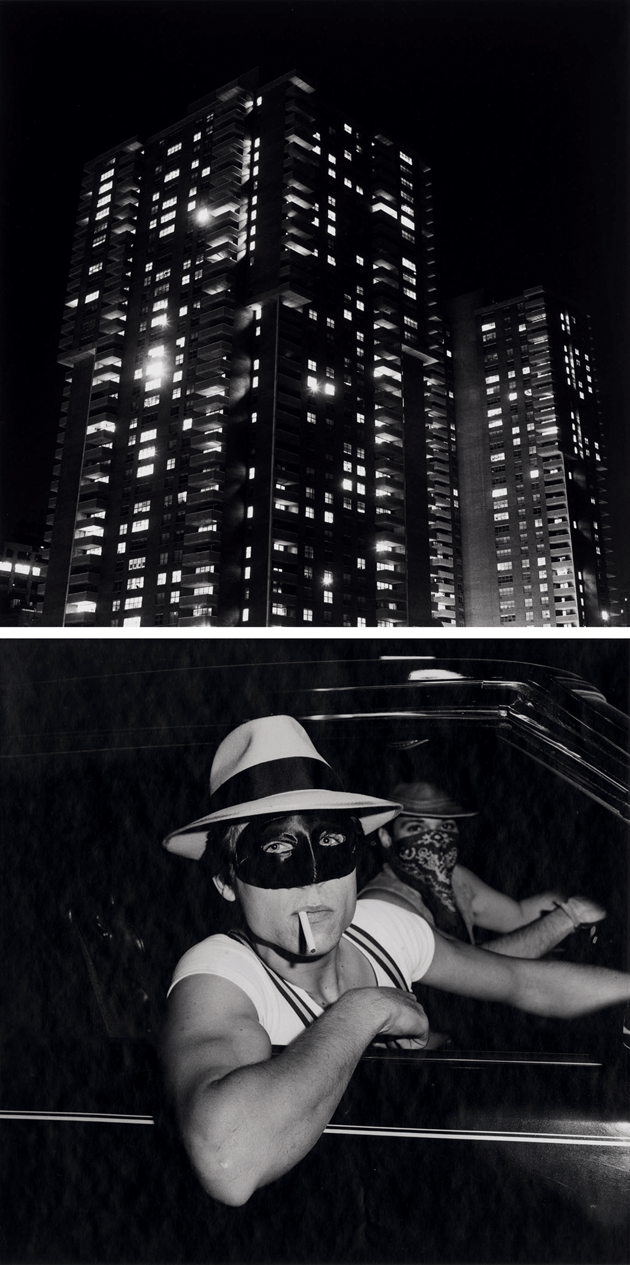

Clockwise from top left: “Ethyl Eichelberger Applying Makeup,” 1982; “Candy Darling on Her Deathbed,” 1973; “Edwin Denby (I),” 1975; “Susan Sontag,” 1975

We were so different that it was almost a kind of bond. Peter’s mother was a waitress in a diner. His father was a small-time bootlegger who abandoned her while she was pregnant. Their gifted son reached adolescence sleeping on the couch in a small, shabby Manhattan apartment, and the night his alcoholic mother hurled an empty gin bottle at him that smashed against the wall, Peter stepped over the broken glass, walked out the door, and never returned. He was sixteen.

I am the son and grandson of Midwestern lawyers. I sidestepped a predictable fate as a third-generation Midwestern lawyer when I hoisted my little leather suitcase onto the luggage rack of a Greyhound bus and watched through its tinted windows as, mile by mile, my Midwest glided away en route to New York City, where I was going to become a writer. I was nineteen.

Peter’s habitat, the Lower East Side, was, I suppose, bohemian. Yet Peter was beyond bohemianism. He’d never known a middle class to reject. As for me, I considered myself a free spirit, an unconventional figure with my books and black turtlenecks who would never, ever be understood by my cousins in St. Paul, Minnesota. Peter, however, was amused and perplexed by my bourgeois oddity. I was quite comfortable in a lawyer’s office. I could read a contract without going blind with fear and bewilderment. I understood that negotiations did not need to end in yelling or swinging barstools.

Even after I broke into print, my books were published by mainstream houses, my articles in mainstream magazines. From the Seventies on, I taught at Ivy League universities, where I fit in just fine, and I managed to cobble together a middle-class income. Peter never did.

We were opposites in other ways too. My growth as a writer was slow, stumbling, and uncertain, while Peter stepped with uncommon confidence into his identity as an artist. By the time he was sixteen, he knew he was a photographer, and just as he seems never to have been particularly troubled by shame, insecurity, or any kind of inner torment over being gay, he did not spend the usual years struggling to find his medium or his style or (most forbidding of all) himself. Peter was always himself, and by the age of twenty-three, he was making masterpieces.

Financially, Peter more or less made his way at first. But after 1973, when he turned his back on commercial photography to focus on his personal work, he seemed to live on nothing. He just about squeaked by from one month to the next, with not even a dollar to spare. Yet he never seemed poor. He just never had any money. Tall, exceedingly handsome, calm, and upright, he seemed entirely sure of himself. But under that self-possession lurked something ominous, even dangerous.

Peter told me about his decision on a stifling July day during the last summer of his life. That afternoon, he was pretty sure the end had come. (It hadn’t; he survived until late November.) I had walked over to his place to take him to Cabrini Medical Center for what he evidently thought would be his final hospitalization. I made my way there through the intolerable July air, sweltering as only New York can swelter, so thick with humidity that it was almost viscous.

At his loft at Second Avenue and 12th Street, Peter was packed but not quite ready to go. The loft was, as usual, in perfect order. He lived in half of it and worked in the other half, which was vacant in a gray, spacious, scuffed way—the neutral other space where most of the portraits were made.

We must have talked a bit, until he didn’t want to talk anymore. Walking had become hard for him, but he began to shuffle around that big, ascetic space as if he were alone. Instinctively silent, I sat in one of the brown corduroy easy chairs that were his sole concession to ordinary comfort. He reached his kitchen space and addressed the big blue table in the center. “Goodbye, table,” he said. Then he turned to the stove. “Goodbye, stove.” The sink came next. “Goodbye, sink. Goodbye, refrigerator.” I sat still, wishing to be invisible. Leaving the kitchen, he crossed to his darkroom and, standing in the doorway, peered in. “Goodbye, darkroom. Goodbye. Goodbye.” Shambling back into the living space, he addressed everything there individually: chairs, bookcase, books, records, stereo, television.

He ignored me.

He turned to the bed where he had sweated through the agony of one opportunistic infection after another. It was immaculately made. “Goodbye, bed,” he said gently. “Goodbye.”

Somehow it came time to go. I stood up. Peter was very weak, just barely able to walk. I picked up his bag and took his arm, and we made our way toward the door. But then he stopped, looked me squarely in the face, and said, “I have decided that you should have the pictures.” Then, knowing that my wife and I were trying to have a child, he added, “Send little Madeleine to college.”

I must have said something. I can’t remember or even imagine what. I do remember exactly what I felt. I felt my destiny changing course. We took a few more shuffling steps to the door. Before we reached it, Peter finished with a typical Hujar stinger.

“You’re no good,” he said. “But you’re the best I have.”

Negotiating the narrow, slummy stairs to the street was a delicate business. I had to help Peter with his balance many times. Once we were in the taxi, he asked me to contact a lawyer and send her to his hospital room as soon as he settled in. He was ready to write his will, he said. He kept gazing steadily out the window. At some point, he murmured, “This is the neighborhood where I grew up.”

Then, after a pause, he turned to me and said, “You’re a dear one, Stephen. You really are.”

I could not reply.

The camera was Peter’s instrument of intimacy. Its lens gave him something he could not otherwise achieve and could not live without: an equilibrium between closeness and distance. He also believed that the camera could reveal things that were invisible to the naked eye. It could show the evidence of people’s inner lives on their bodies and faces, and how they lived in the moment, how they were or were not fully themselves.

Being photographed by Peter sometimes took hours. The room was usually very quiet, except for the clicking camera. He chatted very little. His eyes stayed fixed on you, steadily watching. He walked around. He might say, “This isn’t working, try a different position.” You sensed that he was waiting—waiting for you to tire of being photographed, waiting for the flicker of something that the camera would snatch out of time and reveal as you and nobody else. Such moments come and go quickly. Peter often found them only in the contact sheets. In a portrait of Edwin Denby, the poet and dance critic, the subject’s eyes are closed in what seems an old man’s introspective serenity. In fact, Denby had merely blinked.

Peter had no formula. The special thing the camera saw had to be unique and your own. Anything less was, as he put it, “worthless.” It could be graceful or awkward, pleasing or mortifying, candid or posed. It just had to be real, and it had to be beautiful, in his personal sense of those crucial words.

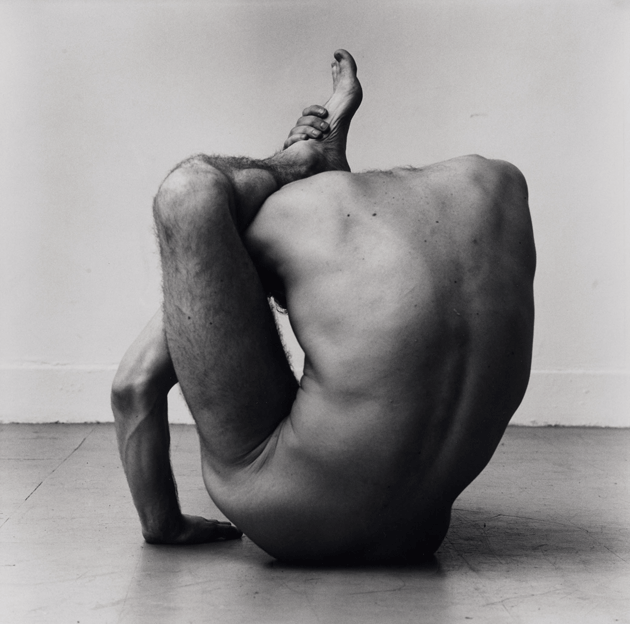

The special thing might be Susan Sontag’s solitary reverie in Peter’s famous portrait of her reclining. Or it could be quite obviously staged, as when he realized the terminal fantasy of a dying transgender actress in “Candy Darling on her Deathbed,” a picture that the philosopher Arthur Danto has called “one of the truly great photographs of the century.” Or it could be caught in a moment when the personality itself is relinquished, or consigned to a sort of ecstatic oblivion, as in “Orgasmic Man.” Your portrait was always unmistakably you, but only because it was also unmistakably his. The intimacy was in his style.

In life, Peter’s intimacy was strictly controlled. His charisma was surrounded by strict boundaries that lay around him like rings. They determined what was possible. The outer circle was wide, and reserved for groups and strangers. It was wonderful. If you define charm as the capacity to seem intimate without the work and risks of real intimacy, Peter could be charming as few people are charming.

Within the outer circle of Peter’s charm lay an inner circle of his friendships. It, too, felt wonderful. According to the photographer Gary Schneider, Peter “made every one of his friends feel like they were his only friend.” There were long, probing conversations. He had absolutely no small talk. Right away, you opened up, and he opened up. He would sit over coffee at his big blue kitchen table, listening as nobody else seemed to listen and responding as nobody else seemed to respond. He made everyone, including me, feel unique.

But inside the inspired circle of his friendship lay an innermost circle—the up-close region where his vulnerability was concealed. That boundary was a kind of circular third rail. You approached it at your peril. Behind it was a reservoir of limitless rage. Was it the rage of the abused child he had been? Whatever the source, it was frightening, often violent, lethal to relationships, and the force behind his profound loneliness. Its high-voltage wire kept him forever trapped inside his all too complex sex life and all too arid emotional life. Anyone who touched his immeasurable neediness threatened to shatter the self-sufficiency that was his most treasured creation, and all he had.

Almost every one of his close friends was subjected to that anger at some point. Oddly enough, I was not. I see now that despite all the good times, I was always a little scared of Peter. Whenever I edged too close to the third rail, some instinct made me retreat. This caution now looks to me like intimidation: I sensed his ire. I could see it coming as his handsome face twisted into a mask of annoyance, indignation, fury. Without fail, I would back off. It worked. I witnessed Peter’s full ferocity only once, when I saw him hurl an unwelcome visitor down the long flight of stairs outside his loft.

Another example: Peter owned, played, and loved a harpsichord. One night, in a pointless frenzy at one of his few serious boyfriends, he seized a hammer and smashed the harpsichord into a heap of splinters and wire. (The boyfriend fled the loft and begged a friend to let him spend the night, afraid that Peter would follow him to his own apartment and kill him.) These gushers of rage were compounded by volcanic irritability over the most trivial things. Once, on a flight to Mexico, he got into a screaming fight with a flight attendant over a tray of breakfast buns. The captain ordered him confined to his seat. Upon landing, he and the captain quarreled so violently on the tarmac that Peter narrowly missed being tossed in jail. Over a tray of breakfast buns!

During the time I knew him, only one person was untouched by this rage. Only one reached the center of his intimacy. In 1981, a spectacularly talented young man named David Wojnarowicz entered Peter’s life. The two met in a bar, and after a brief sexual interlude, they formed what amounted to an alternative familial bond. When they met, David’s life was chaotic, imperiled by drugs, and his prodigious talent was unfocused, juvenile, and mainly wasted. David desperately needed a father, and as the shadows lengthened, Peter just as desperately needed a son. David craved a mentor, a guide out of his chaos, someone who could see his soul. Peter craved renewal, restoration of his life, someone whose soul he could see and who was worthy of whatever Peter could give him.

For David, and David alone, there was no third rail. In life, he was gawky and awkward and had a bad complexion. But Peter’s portraits of him make him look like a serene young god. David, for his part, did not share Peter’s paralysis over success. If they had lived, who knows what might have happened? But David succumbed to AIDS in 1992, five years after Peter.

“Everything I made,” David once said, “I made for Peter.” That was intimacy. And it gave Peter six years of grace before the end.

After Peter died, I embarked on my mission knowing exactly nothing. Nothing about galleries, curators, museums, critics, collectors, shows, auctions, conservation, inventories, digitization, databases, art storage, or the public. Shortly after his standing-room-only funeral in a Catholic church in Manhattan, Peter’s friends organized a private memorial, lining the walls of his loft with a hasty but beautiful exhibition of his work. I was there only briefly. I feared all those people who were so pissed off at me.

Yet Peter’s estate chalked up its first sale on that occasion: Robert Mapplethorpe bought “Running Horse” on the spot. He paid $500 for it, thanks in part to the fact that I had already announced that no Hujar print would sell for one penny less than $500. Enough with this cringing obscurity! It seemed a bold move, and I was proud of it.

Of course, Peter had died without a dealer. His exchanges with dealers almost always ended in tumult or disaster. He saw his own behavior as a crippling psychic curse, rightly feeling that he simply could not allow himself to be commercially successful. Yet perhaps his maddening lack of success was somehow necessary to his achievement. In any case, I now needed to find him a dealer, and fast. I started at the top and made many calls, knocked on many doors. Yet everywhere I turned in the art world, I heard the same question: “Peter who?”

One notable dealer told me that while Peter was clearly gifted, the most I could hope for would be a tiny coterie of homosexual collectors. Another agreed to come to the little office where I stored the pictures. I had laid out all the boxes, and my visitor started looking. He was chatty and relaxed, but I could see that he was looking with obvious expertise and intelligence. When he was finished, he said that Peter was clearly a great photographer, but his reputation needed building, and I should check back later.

At one point, I thought I had a nibble from Maria Morris Hambourg, the formidable photo curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. With some encouragement, I had filled a box with fifty of Peter’s best pictures and simply dropped it off at her office. Not only would I spare her the vulgarity of a pitch, she wouldn’t even have to lay eyes on me. She could look or not look as she pleased. And she alone would decide when to return the box.

A rather long time later, my phone rang, and Hambourg herself was on the line. She invited me to the Met for tea. I was escorted through a mighty maze of corridors in that palatial edifice and shown into a small, lovely room that the public never got to see. There sat Hambourg, and there was the tea. After the niceties, she told me that she had looked carefully at the pictures and concluded that Peter was indeed a great photographer. She would very much like to give him a show at the Met.

I sat very still and kept calm, thinking this-is-it, this-is-it, this-is-it, this-is-it, the moment. Then came the but. Hambourg urged me to keep two things in mind. First, given the Met’s long-term planning, we would probably both be old and infirm before such a show could open. Then came the clincher. “You must remember,” she said. “I have a very conservative board of directors.”

It was the most elegant no I received.

I have developed a little parable about success in the arts, or at least about Peter’s posthumous success. You are managing a body of work that you know is wonderful, but you are confronting a brick wall. Success waits on the other side. What to do? You look for cracks in the wall. There aren’t any. You try to dig under it. You try to climb over it. No way. So you try to knock the wall down. You kick it, you slam your body against it, thinking you must be nuts, this is so obviously futile. Besides, it hurts—a lot. Your body is bruised. Your shirt is in rags. Your shoulder is bleeding. And the wall, of course, hasn’t budged one millimeter.

Then, a hundred feet away, an entirely different brick wall, one that you’ve never even noticed before, suddenly topples over. That’s how it was. I never stopped banging, yet every really important event in Peter’s resurrection came as a surprise, off somewhere in the middle distance.

Peter had been dead two years when the first of these walls came tumbling down. The director of the Grey Art Gallery at New York University announced that he wanted to do a big show of Peter’s work. A large, if unfocused, exhibition was assembled. Many prints had to be prepared, and for that I hired a skilled young technician whose regular job was with Richard Avedon, then America’s most celebrated photographer. One night, he was working on this freelance gig while at Avedon’s studio, and as he hunched over Peter’s prints, Avedon strolled in.

“What’s all this?” the master asked.

Avedon sat down and started looking. Then he looked some more. He didn’t stop looking even when his assistant packed it in for the night, and the next morning, he asked him to convey to me his strong interest in the show. In fact, I was told, Avedon would very much like to hang it himself.

Hang the show himself? I was thrilled by the affirmation and by the wild, dumb luck of it. Trembling with exhilaration, I called the Grey Art Gallery with the glorious news. It was greeted with flinty silence. In my innocence, I had failed to grasp that this show was a career move for the director, and he did not want to have his leading role overshadowed, even (or especially) by the likes of Richard Avedon. None of my many arguments softened his stony refusal. (Asked for comment, the former director said he did not recall an offer from Avedon.) I found myself sitting down to the desolate task of composing a letter to the nation’s preeminent photographer, thanking him for his interest and his extraordinarily gracious offer of support but most respectfully and most regretfully declining.

I never heard from Avedon again.

In the Nineties, more walls suddenly tumbled down. First, a discriminating young dealer named James Danziger took on Peter’s work, spurred by a recommendation from Gary Schneider, Peter’s friend and fellow photographer. Danziger went on to organize several shows of Peter’s work, and sold Peter’s portrait of a reclining Susan Sontag to Annie Leibovitz. Then, in 1994, two curators, Hripsime Visser of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and Urs Stahel of the Fotomuseum Winterthur, in Switzerland, mounted a full-scale retrospective, complete with multiple venues and a sophisticated catalogue. Peter’s star was finally on the rise. Though there was still no European dealer, his work was shown in Zurich, in Berlin, in Brussels. In 1996, Peter was included in a modest three-person show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art—the first major American museum to give him space after his death.

It was around then that I had the first of many almost identical dreams, which recurred over the years more times than I can count. In each dream, I would be at home when I heard that Peter was back from the dead. He was alive again, and he was waiting to talk with me in somebody’s loft in SoHo. I would jump into a cab, and on the ride downtown a wave of sadness would wash over me as I realized that now I would have to return his work, to which I had become very attached.

The first time I had the dream, I reached the loft, and there stood Peter, looking as healthy and handsome as he did before he got sick. I greeted him joyfully, but my joy was not reciprocated. Instead, his face was twisted into exactly the mask of impending violence that came when you edged too close to the third rail. I stepped back. He asked what I had been doing, but when I started telling him, he interrupted brusquely. “Wrong! Stop! Not one more word!” Every move I’d made was stupid, incompetent. The whole enterprise was a disaster. He would never forgive me.

I didn’t try to justify myself. I groveled. I stammered useless apologies. His fury did not subside. Peter wanted me out of his resurrected life forever. And he wanted his work back now, this minute, this instant.

I started awake. It’s just a dream, I told myself. Surely I had done better than that. Hadn’t I? Each time, I felt terrible. But each time, I sensed that Peter was maybe just a little less angry. Could that be true?

Dream or no dream, Peter’s posthumous career kept picking up momentum. When Danziger closed his gallery, I got calls from several powerful dealers and ended up going with Matthew Marks, who represented many big stars: Lucian Freud, Brice Marden, Ellsworth Kelly, Nan Goldin, Jasper Johns. In New York, a dazzling show of his work—in some ways, the best yet—was staged at MoMA PS1, the contemporary branch of the Museum of Modern Art. As I walked through it again and again, I noticed that the place was thronged with people under thirty-five. They had been children, or not yet born, when Peter died. Now, what was that about? It must mean something.

My job grew ever more demanding. I hired an assistant. The whole body of work was digitized. Major museums and collectors were buying. The poorest adult I had ever known had transformed me into what I had never even wanted to be: a rather successful small businessman.

While all this was happening, the dreams kept on coming. But they began to change. Now the resurrected Peter would sometimes welcome me politely and actually smile. Later, the old charm came back. So did the hasty fraternal embrace. Our discussion about returning his work was easy, almost fun. I was beginning to enjoy the damn dreams.

Until one night the old dream returned. When I walked into the usual loft downtown, the place was as tense as a courtroom in which some criminal is about to be sentenced to death. Peter stood in the center, radiating all the rage that I had so often managed to evade. The attack began. He condemned me. He denounced me. The tirade didn’t stop, and every sentence was crueler than the last.

Feeling an unfamiliar sense of calm, I finally spoke up. “Peter,” I began, “I want to say from the bottom of my heart that I am thrilled that you are back from the dead. And I’ll be returning every scrap of your work, starting tomorrow morning. But before I do, let me say something. In the many years since you died, I have managed to pull your wonderful work out of the dank little hole where you left it. Because of its quality, and my efforts, it is now in many of the major museums of the world. Critics and journalists on three continents write respectfully about you. Curators and collectors clamor for your photographs. Your work is widely published. You have a large, enthusiastic following among the youth of not one but two new generations. And if there is something in that state of affairs that you find less than satisfactory, I suggest you go fuck yourself.” I jolted awake.

I have not had the dream since.

Peter now stands on the threshold of the pantheon. Major critics have declared that he belongs “among the greatest of all American photographers.”

By age twenty-three, Peter felt certain that he was destined to be famous. That conviction never changed, and when the passing decades left him still obscure, he was sure he would be famous after his death. Somehow I was sure of it, too. In retrospect, I’d say his quiet charisma in life was somehow luminous, as if he were already famous, but secretly so—famous before the fact.

Now recognition has come. For thirty years, my job has been to bring Peter’s work to the big world. In the future, the big world will come to Peter’s work. I have lived a long time with these images, and they never bore me, never pall. Each year they look better, aging into a durable beauty that was once hard to see and is now obvious. My task is far from over, but as time goes by, I will matter less and less. Finally, I won’t matter at all, because, as Auden said about Yeats in his elegy, Peter will have become his admirers.

Peter grew up abused and in hardship, and he created his great body of work in obscurity, poverty, and against all odds, but no difficulty could stop him. He never faltered. He always knew exactly who he was and exactly how to turn the damaged world he saw around him into images that are whole, beautiful, and his own.

He has triumphed.