In the fall of 1969, I was a freelance journalist working out of a small, cheap office I had rented on the eighth floor of the National Press Building in downtown Washington. A few doors down was a young Ralph Nader, also a loner, whose exposé of the safety failures in American automobiles had changed the industry. There was nothing in those days quite like a quick lunch at the downstairs coffee shop with Ralph. Once, he grabbed a spoonful of my tuna-fish salad, flattened it out on a plate, and pointed out small pieces of paper and even tinier pieces of mouse shit in it. He was marvelous, if a bit hard to digest.

Lieutenant William L. Calley Jr. arrives at a pretrial hearing before his court-martial for his involvement in the My Lai massacre of March 16, 1968 © Bettmann/Getty Images

The tip came on Wednesday, October 22. The caller was Geoffrey Cowan, a young lawyer new to town who had worked on the McCarthy campaign and had been writing critically about the Vietnam War for the Village Voice. There was a story he wanted me to know about. The Army, he told me, was in the process of court-martialing a GI at Fort Benning, in Georgia, for the killing of seventy-five civilians in South Vietnam. Cowan did not have to spell out why such a story, if true, was important, but he refused to discuss the source for his information.

Having covered the Pentagon for the Associated Press, I knew there was a gap between what the men running the war said and what was going on. The lying seemed at times to be out of control, and there were reasons to believe the war was, too. Even those who supported the war in Vietnam were troubled by the reliance on body counts in assessing progress; it was clear that many of those claimed to be enemy soldiers killed in combat were civilians who may have been in the wrong place at the wrong time, or just were there, living where their ancestors had lived for generations.

A question I’ve been asked again and again by others, and have asked myself, is why I pursued Cowan’s tip. There was not much to go on. I did not know Cowan. I had not been to South Vietnam. There had been no public mention, not a hint, of a massacre on the scale cited by Cowan. The answer came from my days in the Pentagon pressroom, where such a rumor would be dismissed by all, so I believed, without a second thought. My colleagues had scoffed at Harrison Salisbury’s firsthand account of systematic American bombing in North Vietnam, which had been published in the New York Times in late 1966. A few had gone further, actively working with Robert McNamara and Cyrus Vance to undercut Salisbury’s dispatches. I chased Cowan’s vague tip because I was convinced they would not.

If Cowan was right, it was the US Army itself that had filed the murder charges. If so, there would have to be some official report somewhere in the military system. Finding it was worth a few days of my time.

I had renewed my Pentagon press credentials because I was writing a book about military spending for Random House, a project that required access to the building. My first step was to review all the recent courts-martial that had been initiated worldwide by the Judge Advocate General’s Corps, the Army’s lawyers. I hurriedly did so, and found no case hinting of mass murder. I went through the same process with criminal investigations that had been made public by the military. Once again, no luck. If Cowan was right, the prosecution he knew about was taking place in secrecy. I felt stymied and went back to collecting data for my book.

What happened next was, in a sense, a one-in-a-million bank shot. First, during a chance encounter at the Pentagon, I got the alleged killer’s name: Calley. Then I spent many hours poring over newspapers on microfilm until I found a three-paragraph clip from the New York Times that had been published six weeks earlier. The report quoted an information officer at Fort Benning to the effect that a twenty-six-year-old infantry officer named William L. Calley Jr. had been charged with murder “in the deaths of an unspecified number of civilians in Vietnam.” The incident took place in March 1968, and nobody in my profession had asked any questions at the time, because no reporter knew what I now did about the enormity of the case.1

I owed my next step to my days as an AP reporter. I had become especially friendly with a senior aide on the House Armed Services Committee, then headed by L. Mendel Rivers, a Democrat from South Carolina with a locked-in seat. Rivers was an outspoken supporter of all things military, including the war in Vietnam, and I was confident that the Pentagon would have given him a private briefing about the mass murders in South Vietnam, if indeed they had taken place.

I managed to have a cup of coffee with my friend on Rivers’s staff. Officials with top-secret clearances were, of course, bored to death by reporters seeking to pry such information from them. So instead of beginning our chat with a question, I simply told my friend everything I knew about Calley and the charges against him. His response was not to deny the story but to warn me off it.

Top to bottom: An American soldier stokes burning houses at My Lai; Vietnamese children about to be shot by US soldiers; Vietnamese civilians killed by the US Army. All photographs © Ronald Haeberle/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images

“It’s just a mess,” he said. “The kid was just crazy. I hear he took a machine gun and shot them all himself. Don’t write about this one. It would just be doing nobody any good.”

I understood my friend’s concern as a senior aide to the very conservative Rivers, but I was not about to stop my reporting. On the other hand, the story, as I was piecing it together, still did not make sense. One young officer did all the killing?

Clearly, I had to find Calley’s lawyer. In desperation, I turned once again to Geoffrey Cowan. It was a cry for help, a shot in the dark. Two days later, Cowan called with a name: Latimer. Nothing more. I did not waste time wondering what else Cowan could tell me, or where he was getting his information.

I found a lawyer named Latimer in the Washington telephone book. He knew nothing about a murder case involving the Vietnam War but thought I might want to get in touch with a George Latimer, a World War II combat veteran who later served as a judge on the US Court of Military Appeals and was now practicing law.

Latimer, I learned, had joined a Salt Lake City law firm, and I got him on the phone. I told him I knew he was representing Calley and added, with some honesty, that I had a hunch his client was being railroaded. (I did not add that I thought he was a criminal.) Latimer, speaking very deliberately, as he always did, acknowledged that yes, Calley was his client and it was a miscarriage of justice. Touchdown! I told the judge I was flying to the West Coast soon and asked whether he would mind if I arranged a stopover in Salt Lake City. We settled on a date later in October, and I spent half a day in the Pentagon library reading a number of his decisions.

I took an early flight and arrived at Latimer’s modest office by ten o’clock on a weekday morning. I guessed the judge, who was an elder in the Mormon Church, to be in his late fifties. It was clear at first glance that he was not a man full of irony and whimsy. I masked my acute anxiety by telling Latimer that I had reviewed a number of his appellate decisions, and asked him to explain why he did what he did in certain instances. He did so. It was an extreme example of the Hersh Rule: never begin an interview by asking core questions.

We got to the case at hand, and Latimer told me that he could not discuss specifics. He did say that the Army had offered his client a plea bargain—one that involved jail time—and he had told them, “Never.” The message was clear: Latimer believed his client was a fall guy for the mistakes, if any, of more senior officers during an intense firefight.

At this point, for reasons I still do not understand, I told Latimer that I understood Calley was being accused of killing 150 civilians during the Army assault on My Lai. The only number I had actually heard cited, however vaguely, was seventy-five. But the Army officer and the congressional aide with whom I had discussed the case spoke of wild shootings and insanity, and I also knew from my readings of other antiwar reportage that the senseless killing of hundreds was commonplace in American attacks on rural villages in South Vietnam.

That fictional number got to Latimer. Visibly angered, he went to a file cabinet, snatched a folder, pulled a few pages from it, walked back to his desk—I was seated across from him—and flung the pages in front of me. It was an Army charge sheet accusing First Lieutenant William L. Calley Jr. of the premeditated murder of 109 “Oriental” human beings. Even in my moment of exultation, it was stunning to see the number Calley was accused of murdering and the description of the dead as “Orientals.” Did the Army mean to suggest that one “Oriental” life was somehow worth less than that of a white American? It was an ugly adjective.

Latimer quickly turned the charge sheet around and pulled it closer to him. I have very little memory of what happened next in our chat, because I spent that time—twenty minutes or so—pretending to take notes as we talked. What I was really doing was reading the charge sheet upside down, albeit very slowly, and copying it word for word.

At some point Latimer broke off the interview and refused to say where Calley was or to help me get to him. I was pretty sure the judge sensed he’d gone too far with me, and I did not dare ask him for a copy of the charge sheet for fear that he would instruct me that I could not use what I had seen. At the door, I thanked him for spending the morning with me and said I assumed that Calley was still at Fort Benning awaiting a court-martial, and that I was going to hunt him down.

Fort Benning, like many Army bases in the United States, was an open facility, and I had no trouble driving onto the main post. I was stunned by its size. The base is nearly the size of New York City, some 285 square miles, with an airfield, a series of widely separated training areas where live ammunition was being fired, and scores of residential areas, known today as family villages. There were a hell of a lot of places to hide Calley, as the Army apparently had chosen to do. I was undaunted; tracking down people who did not want to be found was vital to what I did for a living, and I was good at it.

He was being held on a murder charge, and I assumed that meant he was being kept under wraps at one of the many stockades that were scattered around Fort Benning. I got a good map of the base and began driving. The routine was the same at each prison: I parked my rental car in the spot reserved for the senior officer in charge, which was invariably empty, walked into the prison in my suit and tie, carrying a briefcase, and said to the corporal or sergeant on duty, in a brassy voice, “I’m looking for Bill Calley. Bring him out right away.”

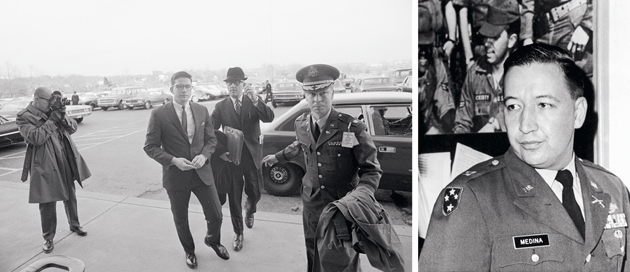

Left: Paul Meadlo (detail), a soldier in Calley’s platoon who confessed to killing civilians at My Lai © Bettmann/Getty Images. Right: Captain Ernest Medina (detail), Calley’s commanding officer © Underwood Archives/Getty Images

There was no Bill Calley anywhere. It took hours and more than a hundred miles to navigate just a few of the stockades scattered around the base, and I was beginning to feel the pressure of time. It was just past noon by the time I returned to the main post.

I found a pay phone and a base telephone directory in a PX cafeteria and began calling every club I could find: swimming, tennis, hunting, fishing, hiking. No member by the name of Calley. None of the gas stations I reached on the base serviced a car owned by Calley. After a frustrating few hours, I still had no clue as to his whereabouts, nor did I know if he was still at Benning. I was hungry, running out of daylight, and more than a little anxious. I decided to take a short walk and a huge risk by stopping by the main office of the JAG Corps, whose lawyers would be prosecuting the case against Calley.

It was long after lunch hour, but the office was empty except for a lone sergeant. He could not have been more friendly as I introduced myself as a journalist from Washington and said I needed some help. His smile disappeared when I said I was looking for William Calley. He asked me to wait a moment. I asked why. He said he was under orders that if anyone asked about Calley, he was to call the colonel right away. That was enough for me. I told the sergeant not to worry about it and began walking away. The sergeant got frantic and said I could not leave. With that I ran out of the office and down the street, going harder with each stride. I did not want a colonel kicking me off the base. The sergeant chased after me for a few dozen yards and then stopped. It was a scene out of a Marx brothers movie.

I had a hamburger and a Coke at a PX and wondered, as I chewed, what the hell to do next. Then I remembered that Latimer had told me that Calley, then still on active duty in Vietnam, had been ordered to fly back to Benning in the summer. I recalled from my AP days that the military produced updated telephone books every few months. I dialed the operator and requested the supervisor on duty, and when she got on the phone, I asked her to check the last batch of new listings in the prior telephone book for a Lieutenant William L. Calley Jr. The lieutenant, when he returned from overseas, had yet to be prosecuted, and he would have been parked somewhere on the base—and duly listed as a late entry in the telephone book.

After a moment or so, the supervisor returned, told me she’d found my man, and then quickly rattled off a phone number and an address before hanging up. I did not understand a thing she said, between my jumpiness and her thick Southern accent, and wasted precious time reconnecting with her. When I did, she spelled out, letter by letter, Calley’s assignment at the base.

He was attached to an engineering unit located in one of Fort Benning’s satellite training camps. The building was only a few miles from the main post, but it took me nearly an hour, driving through a maze of streets, to find the goddamned place. It was the living quarters for trainees and consisted of two three-story barracks linked by a one-story headquarters office. It was midafternoon, a few hours before the workday would end, and I had a premonition that I would find my quarry stashed somewhere inside.

After a few moments of scuffling about, I found a back door into the nearest barracks and walked through row after row of double bunk beds on the first floor, all empty and all neatly made up. I raced through the upper two floors, peering into each bed in the hope of finding my man. Nothing. I crossed to the second barracks, avoiding the officer in charge by scrambling past the door of his office. The eureka moment, or so I thought, came on the second floor, in the form of a young man, in uniform, with tousled blond hair, dead asleep in a top bunk.

I raised a leg, kicked the side of the bunk, and said, “Wake up, Calley.” The soldier, not yet twenty years old, yawned and said, “What the hell, man?” I do not remember what the name tag on his blouse said, but it was now clear that I did not have Calley. I sat down in disappointment on a bed facing the GI, and a question popped out: “What the fuck are you doing sleeping in the middle of the day?”

It was an absurd story. He had been scheduled to be released months earlier from active duty, but the Army had lost his papers and he was still waiting for them. He was from a farming family in Ottumwa, Iowa, and it was harvest season, and his dad and others were doing his share of the work. Meanwhile, he was getting in a lot of sleep. I asked the sad sack whether he had been assigned anything to do during the day. “I sort the mail,” he said. For everyone? Yes. Did he ever get mail for someone named Calley? “You mean that guy that killed all those people?” Yes, that guy.

The farmer-to-be told me that he had never met Calley but had been ordered to collect the lieutenant’s mail and deliver it every so often to his pal Smitty, the mail clerk at battalion headquarters. The unhappy GI then led me to Smitty, who in turn offered to show me Calley’s 201 file: the personnel folder that the military keeps for both enlisted men and officers.

Trying to stay cool, I opened the folder, and the first page that I encountered was the same charge sheet I had seen days earlier in George Latimer’s office. There was more: an address, in nearby Columbus, Georgia, where Calley was living. I took the time to carefully copy the charge sheet, making sure I got every phrase right, and returned the file to Smitty. He was glad to help, he said—fuck the Army. Then he left, and I headed for Calley’s new home.

It was nearly five o’clock by the time I got to Calley’s condo in what seemed to be a new housing development. A car pulled into the driveway ahead of me, and three young second lieutenants dressed in camouflage fatigues climbed out. I parked behind them, got out of the car, and explained that I was a journalist in search of Bill Calley. Didn’t he live here? Not anymore, I was told.

They invited me in for a drink and explained that they were June graduates from West Point, finishing up combat training before heading off to Vietnam as infantry platoon leaders. They were polite, articulate, and very likable.

We had another bourbon or two. Calley, I learned, stopped by occasionally to get his mail. Of course they knew where he was living now, but they volunteered nothing—until one finally broke ranks as I was leaving. Calley, he told me, had been tucked away in the senior quarters for field-grade officers, including colonels and generals on temporary assignment to Benning. I was stunned: A suspected mass murderer hidden away in quarters for the Army’s most elite? I never would have looked there. It would have been like finding Calley in a neonatal intensive care unit.

I drove off to the complex of two-story buildings with a large parking lot. I began knocking on doors, calling out as I did, “Bill? Bill Calley?” Over the next few hours, I got through two of the three buildings, with no luck and much exhaustion. I’d gotten up at five o’clock that morning in Washington and had little to eat and more than I needed to drink. It was time to check into a motel, get an hour or two of sleep, and start knocking on doors again.

It was dark as I walked across the nearly empty parking lot. I noticed two guys working underneath a car a few hundred feet away with the aid of a floodlight. I vividly remember thinking to myself: let it go, you’ve done enough for today. But I didn’t. As I got close to the car, I apologized for bothering the two guys but said I was looking for Bill Calley. One of the men, perhaps in his late forties, crawled out and asked what I wanted with him. I explained that I was a journalist from Washington and that Calley was in a lot of trouble, and the man invited me to wait for him at his place.

His place turned out to be on the first floor of one of the units, and Calley lived above him. I was warned that it might be hours before Calley showed up; he had gone motorboating at a lake miles away. Yes, said my new friend, a senior warrant officer who flew helicopters in heavy combat, he knew Calley was in a lot of trouble.

Drinks were offered as we waited; the US Army clearly was running on bourbon. He understood where I was coming from, he said, and acknowledged, sadly, that Vietnam was a murderous, unwinnable war that was taxing his love for the military. Calley was worried, the pilot said, as he should be. His story of a firefight would not hold up. I liked the pilot and admired his honesty, but after an hour or so of pretending to sip a drink, I was done. I had to get some sleep. I said goodbye—I can still see the mosquitoes buzzing around a naked bulb outside his door—and began walking to my car.

“Hersh!” the pilot yelled. “Come back! Rusty is here.”

It was Calley. We shook hands. I told him who I was and that I was there to get his side of the story. He said, as if my tracking him down had been a piece of cake, that yes, his lawyer had told him to expect a visit from me.

We went upstairs. I had another drink—this time a beer—and we began to talk. I had wanted to hate him, to see him as a child-killing monster, but instead I found a frightened young man, short and so pale that the bluish veins on his neck and shoulders were visible. His initial account was impossible to believe, full of heroic one-on-one warfare with bullets, grenades, and artillery shells exchanged with the evil commies.

Sometime after three in the morning, Calley took me to a PX, where he bought a bottle of bourbon and some wine. The next stop was an all-night store on the base, where he purchased a steak. Then we picked up his girlfriend, who was a nurse on night duty at the main hospital at the base. She was enraged at Calley upon learning that he was introducing her to a journalist, but she drove back to his apartment with us and made dinner. There was more drinking, and as daylight broke, Calley was talking about going bowling.

The nurse had fled by then, and I had compiled a notebook full of quotes, many of them full of danger for him: his account of the assault at My Lai had become more and more riddled with contradictions. As I got up to leave, Calley insisted that I have a brief phone conversation with his captain, Ernest Medina, who had been in charge of the assault at My Lai.

Medina, who would be found not guilty of premeditated murder, involuntary manslaughter, and assault after a court-martial two years later, picked up the telephone after a ring or two. He also was at Fort Benning, presumably going through the same process as Calley, who was sharing the phone with me. Calley explained that he had been talking to me about My Lai, and he asked Medina to confirm that anything that took place was done under his direct orders. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Medina said, and then he hung up. Calley looked stricken. At that moment, he finally grasped what I am sure he had already suspected: he was going to be the fall guy for the murders at My Lai.

I’d been a reporter for a decade by the fall of 1969 and somehow had figured out that the best way to tell a story, no matter how significant or complicated, was to get the hell out of the way and just tell it. My first My Lai dispatch thus began:

Lt. William L. Calley, Jr., 26, is a mild-mannered, boyish-looking Vietnam combat veteran with the nickname of “Rusty.” The Army says he deliberately murdered at least 109 Vietnamese civilians during a search-and-destroy mission in March 1968 in a Viet Cong stronghold known as “Pinkville.”

I wrote the story to the best of my ability and then telephoned an editor friend at Life and said it was all theirs, if the weekly moved quickly. The editor called back within a few hours and said no. He had pushed for it, he said, but there was little enthusiasm for such a story on the part of senior management. I had also been in touch earlier with Look, and now called the editor there and filled him in on the Calley interview. He, too, passed.

I was devastated, and frightened by the extent of self-censorship I was encountering in my profession. I feared I would have no choice but to take the My Lai story to a newspaper and run the risk of having editors turn over my information to their reporting staff: in other words, of being treated like a tipster.

I had stayed in touch with the famed Washington muckraker I. F. Stone through my recent travails, and he responded to my desperation by assuring me that Bob Silvers, the editor of The New York Review of Books, would publish the piece immediately. I called Silvers and he had me dictate the story to someone there. When he and I talked, Silvers told me how excited he was about the story. He had only one significant editing request. Would I add a paragraph up high in the piece to explain the meaning of the massacre, putting it in the context of a brutal, unwinnable war?

I was familiar with editors wanting to put their fingerprints on a good story, and laughed him off, saying there was no need to spell out for readers the political importance of the case against Calley. Surely the facts spoke for themselves. Silvers insisted. I refused. He said he would not run the story without adding the words he wanted me to write. I said goodbye, and that was that.

I was adamant because I knew from my years of being immersed in the war, and in the racism and fear that drove it, that the mass murder of civilians was far more common than most people suspected—and that it was very seldom prosecuted. We now had a case where the Army itself was drawing a line and saying, in essence, that there were some actions that could not be overlooked. There was no way I would let even one paragraph that smacked of antiwar dicta pollute the straightforward report of a mass murder I had written, even if it was to be published in a magazine that was conspicuously against the war.

The flap with Silvers, someone who was on my side, proved to me that I wasn’t going to get the My Lai story published the way I wanted, not unless I somehow put it out there myself. I called up my friend David Obst, who ran the Washington-based Dispatch News Service, an antiwar agency formed just a year earlier. I told him that he could have the goddamned story and that he’d better not screw it up. I also told him that Dispatch News Service was going to copyright the My Lai story and take full responsibility for publishing it. The newspapers who chose to print what we wrote would pay a fixed fee for doing so, and we settled on a hundred bucks per paper, regardless of circulation. I somehow had faith that Obst, a twenty-three-year-old who was able to talk himself in and out of trouble with great charm and pizzazz, would pull it off.

In its own way, what Obst accomplished was as unlikely as my running down Calley at Fort Benning. In his 1998 memoir Too Good to Be Forgotten, he recalled how he went about selling the story, starting early in the morning on November 12, 1969:

I got a copy of a book called The Literary Marketplace, which listed the names and phone numbers of all of the newspapers in America. I opened to A and began calling. It wasn’t until I got to the Cs that I got a hit. The Hartford Current [sic] in Connecticut said they were interested and requested a copy of the story.

My only effort to sell the story on that same day ended in something of a fiasco. I was a good friend of Larry Stern, a star reporter on the national staff of the Washington Post, and he invited me to meet with Ben Bradlee, the paper’s magnetic executive editor. I showed up there just after noon with Michael Nussbaum, my lawyer and also an old friend, and we met in the tiny office of Phil Foisie, the foreign editor. Four or five editors and reporters gathered around as I distributed copies of the Calley story. There was quiet as all began to read. It was broken by the effervescent Bradlee, who literally tossed the pages he was reading at Foisie and said, “Goddamn it! I’ve got hundreds of reporters working for me and this has to come from the outside. Publish it. It smells right.”

Despite Bradlee’s drama-queen performance, the Post totally rewrote my story, adding denials from the Pentagon and other caveats. At least they put the article on the front page. The early edition hit the street well before midnight. It was an ignoble beginning, made worse when Peter Braestrup, who had been assigned to rewrite my Calley story, woke me up a few hours before dawn to tell me that I was a lying son of a bitch: no single soldier could be responsible for the murder of 109 civilians. It was just impossible, he insisted.

I thought Braestrup was drunk, but he may not have been. In any case, I had a lot of trouble going back to sleep. As he reminded me, I had reported a mass murder without having seen a shred of video or photographic evidence.

I would soon learn that the My Lai story made a lot of people irrational. My telephone at home remained listed, as it still is, and for months after the story broke I got calls from angry officers and enlisted men, usually drunk, telling me what they were going to do to my private parts. Braestrup’s was far and away the most stressful case, especially when I learned of his expertise. He was a former Marine officer who had been seriously wounded in the Korean War, and was soon to be the Saigon bureau chief for the Post. I had obviously anticipated pushback from many in the government and the military, but Braestrup alerted me to the possibility that my fellow reporters would be equally resentful.

Obst and I had no idea whether the fifty or so newspaper editors around the country who bought the story would actually choose to publish it until the middle of the next afternoon, when out-of-town papers arrived at the newsstand in the National Press Building. Obst, it turned out, had created a miracle: dozens of major newspapers, including the Chicago Sun-Times, the Philadelphia Bulletin, and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, prominently displayed the Calley story; a few even made it the banner headline. The New York Times did not buy the story, but the New York Post did, and gave it dominant play.

The major television networks did nothing with the story, in part because the Pentagon shrewdly refused to make any comment. And there was widespread skepticism elsewhere in the media about my report, with many newspapers—including the Washington Post—noting the hardships US soldiers were undergoing in fighting a guerrilla war against enemy troops who posed as farmers during the day. The subliminal message was clear: American soldiers were often in a position where they had to shoot first or become victims. Who was I to make such a harsh judgment about the war?2

Within weeks I wrote a follow-up piece, which Obst sold to scores of papers in America and abroad. (The New York Times declined once again.) I kept on going. By now I knew there was yet another story that, so I thought, would end any resistance to the obvious truth of My Lai. I had spoken to other members of Calley’s platoon, and they told me about a soldier named Paul Meadlo, a farm kid from somewhere in Indiana, who had mechanically fired clip after clip of bullets, on Calley’s orders, into groups of women and children who had been rounded up amid the massacre.

I traced Meadlo’s family to the tiny village of New Goshen, about eighty-five miles west of Indianapolis, and pulled up in front of the ramshackle farm at midday. Paul’s mother, Myrtle, in her fifties but looking much older, came out to greet me. When I explained my mission, she pointed to a second, smaller frame house on the property.

I knocked on the door and Meadlo waved me inside. The day after the My Lai massacre, he had stepped on a land mine, which blew off his right foot. I began the conversation by asking him to show me his stump. He took off his boot and prosthetic device and talked openly and with animation about the treatment he had received in the field, in Vietnam, and the long recuperation he went through at an Army hospital in Japan. We then turned to the day of the massacre. Meadlo told the story to me in great detail, and with little emotion, especially given the events he was recounting: Calley first ordered him to guard the survivors of the initial carnage, who had been gathered in a ditch, and then told him to kill them all. There were other soldiers present, but Meadlo did the bulk of the job, firing four or five seventeen-bullet clips into the ditch until it grew silent.

I called Obst late in the afternoon and told him to let editors know we had done it again and now had a front-page story for the world: a firsthand account of the massacre, on the record, from a shooter. Paul Meadlo’s confessional did change America, as I hoped it would. Before his account was published in papers around the world, he was taped for CBS television as well, and his appearance was broadcast on November 24: the same day that the Pentagon formally announced that Calley would be court-martialed for the murder of 109 Vietnamese civilians.

The harrowing Meadlo story ended the debate about what had happened at My Lai, and it also spawned a wave of Sunday feature stories by journalists about massacres they had witnessed in Vietnam. The one that troubled me the most was filed by an experienced AP correspondent, who described how a few Marines had gone on a rampage in 1965 and killed a cluster of civilians who had taken refuge in a cave. My first angry thought: Why hadn’t such stories been published at the time? But I soon took a more charitable tack: My controversial pieces had been written in an office far from Vietnam, and in a climate at least slightly more welcoming to antiwar sentiment. Publishing such an on-the-scene account in 1965 would have been seen by many as disloyalty, and it would have been vigorously (if shakily) debunked, with prominent newspapers leading the pack.

As for me, I continued to race around America well into December, tracking down My Lai participants and witnesses. I produced five articles in all on the massacre and its aftermath for Dispatch News Service. But I have yet to sort out the ethical complexities of what I was writing about, and perhaps I never will. In a letter I sent to Bob Loomis, who was then my editor at Random House, I wrote:

Both the killer and the killed are victims in Vietnam; the peasant who is shot down for no reason and the GI who is taught, or comes to believe, that a Vietnamese life somehow has less meaning than his wife’s, or his sister’s, or his mother’s.

I believed those words then, and still do, but it was a hard-earned belief. One GI who shot himself in the foot to get the hell out of My Lai told me of the special savagery some of his colleagues—or was it himself?—had shown toward young children. One GI used his bayonet repeatedly on a little boy, at one point tossing the child, perhaps still alive, in the air and spearing him as if he were a papier-mâché piñata. I had a two-year-old son at home, and there were times, after talking to my wife and then my child on the telephone, when I would suddenly burst into tears, sobbing uncontrollably. For them? For the victims of American slaughter? For me, because of what I was learning?

My Lai 4: A Report on the Massacre and Its Aftermath, my second book, was published in June 1970. Its publication, to the dismay of many at Random House, was overshadowed by Harper’s Magazine, which published a 30,000-word excerpt of my book, on a different grade of paper from the rest of the magazine, in its May issue, which appeared weeks before the book was available in stores. My shock was tempered by the fact that there were literally lines of buyers outside drugstores and bookstores on the morning the magazine was released. This coup by Willie Morris, the magazine’s editor, certainly put a dent in Random House’s sales, but his instinct about the importance of the story was a boon for the antiwar movement.

The My Lai story undoubtedly hastened America’s withdrawal from Vietnam. On a more personal note, it won me a Pulitzer Prize, some measure of fame, and enough money to make a down payment on a small house in Washington. To this day, however, I feel a certain moral uneasiness about Calley’s role as a fall guy when so many others were equally culpable. Did his conviction somehow let other guilty parties—and even ourselves—off the hook? That was certainly the fear I expressed to Loomis in that letter. It has never entirely gone away:

Calley is really no more at fault than anyone else there: he shouldn’t have been an officer, he shouldn’t have been sent to fight a war he could not comprehend, he shouldn’t have known the body count as the only standard of success, and he shouldn’t be on trial any more than the higher-ranking officers who did nothing about the slaughter afterwards, thus inducing that many more killings. Perhaps there is even less reason to try Calley than the top brass at the Pentagon, or maybe an American president or two, or three. Perhaps you and me should be on trial for not doing more to stop the war.