Serving as a US Air Force launch control officer for intercontinental missiles in the early Seventies, First Lieutenant Bruce Blair figured out how to start a nuclear war and kill a few hundred million people. His unit, stationed in the vast missile fields at Malmstrom Air Force Base, in Montana, oversaw one of four squadrons of Minuteman II ICBMs, each missile topped by a W56 thermonuclear warhead with an explosive force of 1.2 megatons—eighty times that of the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. In theory, the missiles could be fired only by order of the president of the United States, and required mutual cooperation by the two men on duty in each of the launch control centers, of which there were five for each squadron.

In fact, as Blair recounted to me recently, the system could be bypassed with remarkable ease. Safeguards made it difficult, though not impossible, for a two-man crew (of either captains or lieutenants, some straight out of college) in a single launch control center to fire a missile. But, said Blair, “it took only a small conspiracy”—of two people in two separate control centers—to launch the entire squadron of fifty missiles, “sixty megatons targeted at the Soviet Union, China, and North Korea.” (The scheme would first necessitate the “disabling” of the conspirators’ silo crewmates, unless, of course, they, too, were complicit in the operation.) Working in conjunction, the plotters could “jury-rig the system” to send a “vote” by turning keys in their separate launch centers. The three other launch centers might see what was happening, but they would not be able to override the two votes, and the missiles would begin their firing sequence. Even more alarmingly, Blair discovered that if one of the plotters was posted at the particular launch control center in overall command of the squadron, they could together format and transmit a “valid and authentic launch order” for general nuclear war that would immediately launch the entire US strategic nuclear missile force, including a thousand Minuteman and fifty-four Titan missiles, without the possibility of recall. As he put it, “that would get everyone’s attention, for sure.” A more pacifically inclined conspiracy, on the other hand, could effectively disarm the strategic force by formatting and transmitting messages invalidating the presidential launch codes.

When he quit the Air Force in 1974, Blair was haunted by the power that had been within his grasp, and he resolved to do something about it. But when he started lobbying his former superiors, he was met with indifference and even active hostility. “I got in a fair scrap with the Air Force over it,” he recalled. As Blair well knew, there was supposed to be a system already in place to prevent that type of unilateral launch. The civilian leadership in the Pentagon took comfort in this, not knowing that the Strategic Air Command, which then controlled the Air Force’s nuclear weapons, had quietly neutralized it.

This reluctance to implement an obviously desirable precaution might seem extraordinary, but it is explicable in light of the dominant theme in the military’s nuclear weapons culture: the strategy known as “launch under attack.” Theoretically, the president has the option of waiting through an attack before deciding how to respond. But in practice, the system of command and control has been organized so as to leave a president facing reports of incoming missiles with little option but to launch. In the words of Lee Butler, who commanded all US nuclear forces at the end of the Cold War, the system the military designed was “structured to drive the president invariably toward a decision to launch under attack” if he or she believes there is “incontrovertible proof that warheads actually are on the way.” Ensuring that all missiles and bombers would be en route before any enemy missiles actually landed meant that most of the targets in the strategic nuclear war plan would be destroyed—thereby justifying the purchase and deployment of the massive force required to execute such a strike.

Among students of nuclear command and control, this practice of precluding all options but the desired one is known as “jamming” the president. Blair’s irksome protests threatened to slow this process. When his pleas drew rejection from inside the system, he turned to Congress. Eventually the Air Force agreed to begin using “unlock codes”—codes transmitted at the time of the launch order by higher authority without which the crews could not fire—on the weapons in 1977. (Even then, the Navy held off safeguarding its submarine-launched nuclear missiles in this way for another twenty years.)

Following this small victory, Blair continued to probe the baroque architecture of nuclear command and control, and its extreme vulnerability to lethal mishap. In the early Eighties, while working with a top-secret clearance for the Office of Technology Assessment, he prepared a detailed report on such shortcomings. The Pentagon promptly classified it as SIOP-ESI—a level higher than top secret. (SIOP stands for Single Integrated Operational Plan, the US plan for conducting a nuclear war. ESI stands for Extremely Sensitive Information.) Hidden away in the Pentagon, the report was withheld from both relevant senior civilian officials and the very congressional committees that had commissioned it in the first place.

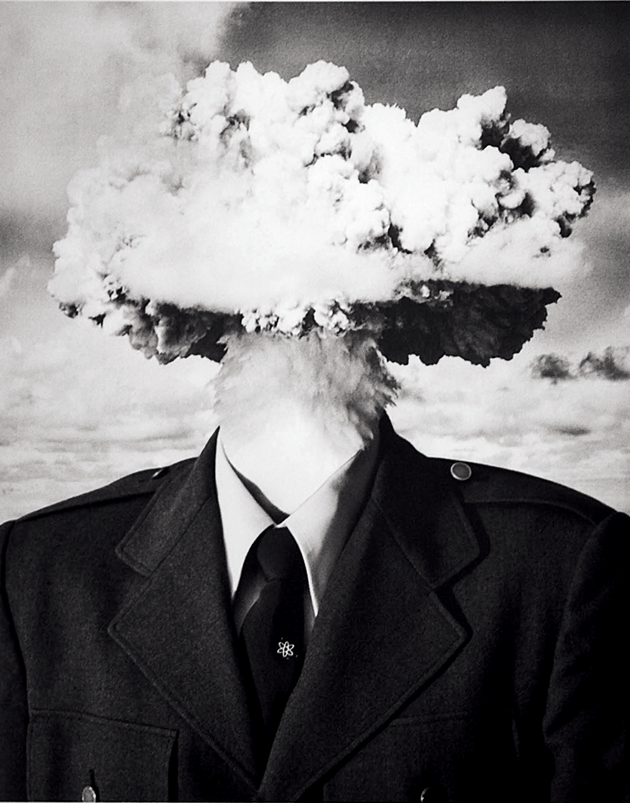

Bombhead, by Bruce Conner © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco, and ARS, New York City. Courtesy Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles

From positions in Washington’s national security think tanks, including the Brookings Institution, Blair used his expertise and scholarly approach to gain access to knowledgeable insiders at the highest ranks, even in Moscow. On visits to the Russian capital during the halcyon years between the Cold War’s end and the renewal of tensions in the twenty-first century, he learned that the Soviet Union had actually developed a “dead hand” in ultimate control of their strategic nuclear arsenal. If sensors detected signs of an enemy nuclear attack, the USSR’s entire missile force would immediately launch with a minimum of human intervention—in effect, the doomsday weapon that ends the world in Dr. Strangelove.

Needless to say, this was a tightly held arrangement, known only to a select few in Moscow. Similarly chilling secrets, Blair continued to learn, lurked in the bowels of the US system, often unknown to the civilian leadership that supposedly directed it. In 1998, for example, on a visit to the headquarters of Strategic Command (STRATCOM), the force controlling all US strategic nuclear weapons, at Offutt Air Force Base, near Omaha, Nebraska, he discovered that the STRATCOM targeting staff had unilaterally chosen to interpret a presidential order on nuclear targeting in such a way as to reinsert China into the SIOP, from which it had been removed in 1982, thereby provisionally consigning a billion Chinese to nuclear immolation. Shortly thereafter, he informed a senior White House official, whose reaction Blair recalled as “surprised” and “befuddled.”

In 2006, Blair founded Global Zero, an organization dedicated to ridding the world of nuclear weapons, with an immediate goal of ending the policy of launch under attack. By that time, the Cold War that had generated the SIOP and all those nuclear weapons had long since come to an end. As a result, part of the nuclear war machine had been dismantled—warhead numbers were reduced, bombers taken off alert, weapons withdrawn from Europe. But at its heart, the system continued unchanged, officially ever alert and smooth running, poised to dispatch hundreds of precisely targeted weapons, but only on receipt of an order from the commander in chief.

The destructive power of the chief executive is sanctified at the very instant of inauguration. The nuclear codes required to authenticate a launch order (reformulated for each incoming president) are activated, and the incumbent begins an umbilical relationship with the military officer, always by his side, who carries the “football,” a briefcase containing said codes. It’s an image simultaneously ominous and reassuring, certifying that the system for initiating World War III is alert but secure and under control.

Even as commonly understood, the procedures leading up to a launch order are frightening. Early warning satellites, using heat-seeking sensors, followed a minute later by ground radars, detect enemy missiles rising above the curve of the earth. The information is analyzed at the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) in Colorado and relayed to the National Military Command Center in the basement of the Pentagon. The projected flight time of the missiles—thirty minutes from Russia—determines the schedule. Within eight minutes, the president is alerted. He then reviews his options with senior advisers such as the secretary of defense, at least those who can be reached in time. The momentous decision of how to respond must be made in as little as six minutes. Using the unique codes that identify him to the military commands that will carry out his instruction, he can then give the order, which is relayed in seconds via the war room and various alternate command centers to the missile silos, submarines, and bombers on alert. The bombers can be turned around, but otherwise the order cannot be recalled.

Fortunately, throughout the decades of confrontation between the superpowers, neither US nor Soviet leaders were ever personally contacted with a nuclear alert, even amid the gravest crises. When Brzezinski, Carter’s national security adviser, was awakened at three in the morning in 1979 by what turned out to be a false alarm regarding incoming Soviet missiles, the president learned what had happened only the following day.

Today, things are different. The nuclear fuse has gotten shorter.

Generally unrecorded by the outside world, there has been a “streamlining” of the system of command and control, as Blair put it in a somewhat opaque article in Arms Control Today. Though the shift, which dates to the George W. Bush era and was additionally confirmed to me by a former senior Pentagon official, may appear to outsiders as a merely bureaucratic rearrangement, it has deadly serious implications. Formerly, attack warnings were received and processed by NORAD, in its lair deep inside Cheyenne Mountain, and passed via the National Military Command Center to the White House. But intelligence of a possible attack now goes almost directly to the head of Strategic Command. From his headquarters, far from Washington at Offutt Air Force Base, this powerful officer, currently an Air Force general named John Hyten, reigns supreme over the entire US strategic nuclear arsenal. He now dominates the whole nuclear countdown process: alerting the president, briefing him on the threat, and guiding him through the various options for a retaliatory or, as is likely given the jamming, preemptive strike.1

At one level, the change reflects a skirmish in the perennial internecine battles for budget share within the military, in which STRATCOM has clearly triumphed at the expense of NORAD, which was relegated to a basement at Peterson Air Force Base in 2006. But it appears there was a more significant motive for the decision. The head of STRATCOM is invariably a four-star general or admiral commanding a global fiefdom of 184,000 people, in and out of uniform. As Hyten reminded a congressional committee this year, “US STRATCOM is globally dispersed from the depths of the ocean, on land, in the air, across cyber, and into space, with a matching breadth of mission areas. The men and women of this command are responsible for strategic deterrence, nuclear operations, space operations, joint electromagnetic spectrum operations, global strike, missile defense, analysis and targeting.”

In contrast, the director of the National Military Command Center is customarily a mere one-star officer, far down in the military pecking order. Furthermore, as befits an administrator, this officer is often absent from the command center buried deep under the Pentagon. On 9/11, for example, the commander at the time was out of the building during the attacks. The actual watch officers pulling eight-hour shifts in the center are colonels, even more lowly and therefore unpardonably reluctant to disturb or wake the commander in chief for what could be a false alarm. Four-stars, on the other hand, are the gods of the military hierarchy, accustomed to deference from all around them. Such panjandrums, especially those with the means to end human civilization, can be expected to have fewer inhibitions against disturbing presidential slumbers.

So it has proved. According to Blair’s high-level sources, Bush and Obama received urgent calls from Omaha on “multiple occasions” during their time in office, and it would seem highly likely that Trump has had the same experience. This March, Colonel Carolyn Bird, the battle watch commander in the STRATCOM Global Operations Center at Offutt, hinted at this privileged access in a CNN report, boasting, “There’s nobody we can’t get on the phone.” Hyten himself dutifully attested to CNN that Trump “asked me very hard questions. He wants to know exactly how it would work,” and sententiously acknowledged that “there is no more difficult decision than the employment of nuclear weapons.” Hyten did not mention that in both actual alerts and exercises, according to Blair, it has sometimes proved impossible to locate and patch in officials such as the defense secretary, despite the fact that the system calls for them to be connected automatically. Thus, in a real or apparent crisis, the crucial and necessarily fraught conversation may be between two men: General Hyten and Donald Trump.

Furthermore, in addition to being shorter, the nuclear fuse may now be lit earlier. For decades, the typical scenario for a nuclear alert began with early warning detection of Russian missiles piercing the clouds over Siberia and following a predictable trajectory. But these days the threats that necessitate those direct calls from Omaha to the White House are more diffuse and ambiguous. Ominous but unverified intelligence reports cite Chinese and Russian progress in hypersonic weapons—missiles that launch toward space and then turn to race toward their targets at five times the speed of sound, allegedly rendering any form of defense impossible. Vladimir Putin has bragged publicly about Russia’s development of intercontinental nuclear-powered cruise missiles and other innovations in his strategic arsenal. (He even personally fired four ballistic missiles in an exercise last October.) North Korean ICBMs, seemingly reliant on a stash of old Soviet rocket engines smuggled out of Ukraine, could supposedly threaten the West Coast of the United States. Iran has tested and deployed home-grown medium-range missiles, as have Pakistan and India.

This new world of multiple threats has sparked public alarm among the military leadership. General Hyten and other powerful officers, for instance, have spoken ominously of the Russian and Chinese hypersonic weapons, maneuvering in unpredictable fashion as they flash toward us at up to five miles a second. Blair has heard the same worries expressed by his sources, and not just about the hypersonics. “There are all kinds of missiles going off all the time now,” he told me. “We’re regularly picking up these launches and trying to figure out what the fuck’s going on.” Presuming that the paths of these supposedly maneuverable weapons are unpredictable, an “imminent” threat no longer necessarily means that enemy missiles are already on the way. Today, the mere suspicion that something is about to happen could be enough for the general in Omaha to phone the presidential bedroom. Hypothetically, given the torrent of incoming and necessarily ambiguous information, intelligence reports that the command crew of a Chinese hypersonic missile squadron have canceled their dinner reservations could prompt such a call and a hurried, lethal decision. The jamming of the president, in other words, can begin earlier than ever.

While Bush and Obama were at the helm, their untrammeled power to launch excited little public concern, even though both men were prone to initiating conventional wars. Obama’s commitment to “modernize” America’s entire nuclear arsenal at a reported cost of at least $1.2 trillion generated no public outrage, or even much concern. According to Jon Wolfsthal, Obama’s senior director for arms control and nonproliferation at the National Security Council, “There is no clear understanding of how much these weapons systems actually cost.” When asked to produce a budget for the entire cost of our nuclear weapons forces, he told me, the Pentagon declined, on the grounds that it would be “too hard” to come up with that figure. But the arrival of Donald Trump, irascible, impulsive, and ignorant, was a different matter, especially given his threats to destroy North Korea with fire and fury. For the first time in decades, nuclear weapons were becoming a matter of public interest and concern.

For the Pentagon, busy extracting more than a trillion dollars from taxpayers to buy and operate an entirely new force of nuclear weapons, Trump’s irresponsible rants cannot have been a welcome development. As Maryland senator Ben Cardin remarked in a Foreign Relations Committee hearing last fall, “We don’t normally get a lot of foreign policy questions at town hall meetings, but as of late, I’ve been getting more and more questions about, Can the president really order a nuclear attack without any controls?” The senators were seeking reassurance that Trump couldn’t really incinerate the planet in a fit of pique, and to that end had summoned a former STRATCOM commander, C. Robert Kehler, as witness.

Kehler, a general who retired in 2013, was evidently anxious to put to rest any unwelcome notions the senators might entertain of overhauling the existing nuclear command system: “Changes or conflicting signals,” he warned, “can have profound implications for deterrence, for extended deterrence, and for the confidence of the men and women in the nuclear forces.” As the general chose to depict it, launching the nukes would be a somewhat laborious bureaucratic process, involving “assessment, review, and consultation between the president and key civilian and military leaders” (including their lawyers), which would only then be “followed by transmission and implementation of any presidential decision by the forces themselves. All activities surrounding nuclear weapons are characterized by layers of safeguards, tests, and reviews.” Of course, as a recent commander, Kehler had to have known that in contemporary alerts and exercises it has sometimes proved impossible to get those key leaders (or their lawyers) on the line, let alone find time for “assessment, review, and consultation.”

But if the president determines that the United States is under the threat of an imminent attack, asked Ron Johnson of Wisconsin, “he has almost absolute authority” to launch, “correct?” Kehler gave a reluctant yes. But, persisted Johnson, what if the president (i.e., Trump) issued a completely unjustified strike order? What would Kehler have done? “I would have said I am not ready to proceed,” answered the general. In other words, he would disobey the order.

Asked to comment on Kehler’s statement at a security conference just a few days later, Hyten confirmed that he, too, was fully prepared to defy a direct order from his commander in chief. “The way the process works is this simple: I provide advice to the president. He’ll tell me what to do, and if it’s illegal, guess what’s going to happen?”

“You say no,” prompted the moderator.

“I’m going to say, Mr. President, it’s illegal,” continued Hyten, expressing confidence that the president, rather than brushing his objection aside and brusquely transmitting the order to launch, would obligingly respond, “‘What would be legal?’ And we’ll come up with options of a mix of capabilities to respond to whatever the situation is.”

Neither of the generals provided any example of what might actually constitute an illegal order (Kehler offered only some vague references to “military necessity” and “proportion”), still less any precedent for American military commanders defying civilian authority when ordered to launch an attack. In any event, though their comments may have served their purpose in calming public fears, they were entirely irrelevant. Unless the principal command center has been knocked out, once the president gives his order the STRATCOM commander has no role in actually executing the nuclear strike. He sees a presidential launch order at the same time as the other command centers that execute it.2

In the event that a commander did choose to defy the president, the former senior Pentagon official suggested, it could even lead to a situation where officers in the launch centers would be receiving contrary orders through different channels, leading to what he called “the biggest shitstorm in the world.”

Despite the generals’ reassurances and Kehler’s plea to leave things alone, there are moves to curb the president’s “absolute authority” to push the button. In September 2016, Ted Lieu, a Democratic congressman from California, introduced legislation, along with Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts, to prevent the president from calling a first strike without congressional approval. Lieu, a former member of the Air Force judge advocate general well versed in the laws of war, could not see any legal justification for the president to unilaterally launch such an attack. The framers, he pointed out when we discussed the matter recently, gave Congress the power to declare war. “There’s no way they would have let one person launch thousands of nuclear weapons that could kill millions of people in less than an hour and not have called that war. If you don’t call that war, you run down the Constitution.” He was unimpressed by the STRATCOM generals’ pledge to defy an illegal launch order and hence felt the urgent need for legislation. “Do we really want to depend on military officers not following an order?”

Not only would Lieu’s bill, which has attracted eighty-one cosponsors, preclude Trump from dropping a nuclear weapon on Syria “because he’s angry at Assad” or some similarly impulsive initiative, it would also, he suggested, prevent launching in response to intelligence of a potential threat (it would not, however, prevent a US nuclear response in the event of incoming missiles). As he reminded me, intelligence has a poor record on threat warnings. “We had intelligence that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, and it turned out they didn’t.” He also cited the near-disaster of Brzezinski’s late-night wake-up call.

In the past, it should be noted, reliance on intelligence warnings has brought us closer to disaster than we knew. In the Fifties, General Curtis LeMay, the father of the Strategic Air Command, secretly deployed his own fleet of electronic intelligence planes over the Soviet Union. “If I see that the Russians are amassing their planes for an attack,” he told a visiting emissary from Washington, Robert Sprague, “I’m going to knock the shit out of them before they can take off.” “But General LeMay, that’s not national policy,” cried a horrified Sprague. “I don’t care,” replied LeMay. “It’s my policy. That’s what I’m going to do.”

In the event that faulty intelligence had actually led to a launch order during the Cold War, the civilian leadership would have been kept in the dark as to what was on the target list, just as they were unaware that LeMay planned to launch World War III on his own initiative. It is well known, for example, that since the early Sixties the war plan has contained “counterforce” options allowing the president to strike military targets while “withholding” attacks on cities. Brilliant minds at the Rand Corporation and elsewhere labored to design such flexibility and have it adopted as policy. But in reality, the distinction was a fiction. War plans enjoined at the highest level were simply ignored by those charged with implementing them. As Franklin Miller, the director of strategic forces policy in the Office of the Secretary of Defense during the Eighties, later explained, whatever the civilian leadership devised, the Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff at Offutt Air Force Base totally controlled the actual selection of targets and the weapons assigned to destroy them. If the civilians ever asked for specific information, the planners in Omaha coolly replied that they had “no need to know.” So successfully did the Offutt targeters guard their turf that even the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the presiding military bureaucracy at the Pentagon, were reportedly denied access to their internal guide for assigning targets. Sheltered by secrecy, the planners were able to define “city” in their targeting guidance so narrowly, Miller later wrote, that had the president ordered a large-scale nuclear strike against military targets with the “urban withhold” option, “every Soviet city would have nonetheless been obliterated.” The degree of overkill was extraordinary. One small target area, for example, five miles in diameter, was due to suffer up to thirteen thermonuclear explosions.

Things should be different today. Mild-mannered and professorial, Kehler and Hyten present a striking contrast to the bellicose, cigar-chewing LeMay, who promised to reduce the Soviet Union to a “smoking, radiating ruin at the end of two hours,” or his successor as head of the Strategic Air Command, General Thomas S. Power, whom even LeMay reportedly considered “not stable” and “a sadist.” Modern communications ensure tighter command and control. The national nuclear weapons stockpile, which peaked at more than 30,000 in the late Sixties, has now passed 6,000, of which some 1,800 are deployed on missiles and aircraft.

But the reduction in numbers obscures the staggering amount of destruction baked into today’s war plans. Blair has published an authoritative estimate of America’s global targets, identifying at least 900 such designated aimpoints for US missiles and bombers in Russia, of which 250 are classed as “economic” and 200 as “leadership,” most of them in cities. Moscow itself could be subject to a hundred nuclear explosions. Poverty-stricken North Korea supplies eighty targets, while Iran furnishes forty. “These are still just huge numbers of weapons,” Blair said to me recently. “The targets are still in those three categories: weapons of mass destruction—which means nuclear—war-sustaining industry, and leadership, same as they always were.” Much of the drawdown in warhead numbers, sanctified by arms control treaties, has been thanks to military confidence that both weapons and intelligence have become more accurate, meaning that fewer weapons need be assigned to any given target. Thus, whereas targeting plans once called for destroying every single bridge along a key Russian railroad, current aimpoints are far more select—destroying just one bridge to shut down the whole line. “They have gotten smart about where the real entrances are to command bunkers,” says Blair. “You usually have a whole set of fake entrances, so you have to put down ten weapons on one major command post. Now we have intelligence on where the actual entrance is, so you only need one weapon for that.”

Such confidence may be misplaced. The 1991 Gulf War was hailed at the time as a triumph of precision targeting and intelligence, as demonstrated by videos of missiles homing in unerringly on their targets. Yet a subsequent and exhaustive inquiry by the Government Accountability Office found that far from precision-guided-bomb maker Texas Instruments’ claims of “one bomb, one target,” it had required an average of four of the most accurate weapons, and sometimes ten, to destroy a given target. A Baghdad bunker destroyed in full confidence that it housed a high-level Iraqi command post had in fact sheltered some four hundred civilians, almost all women and children, most of whom were incinerated.

Even so, the Pentagon is working hard on developing the B61-12, a nuclear bomb that not only incorporates all the most desirable precision-guidance features but is also one of several “dial-a-yield” weapons in the US inventory, meaning that its explosive power can be adjusted as desired, in this case from as little as 0.3 kilotons (equivalent to 300 tons of TNT) all the way up to fifty kilotons. Such programs, as with the low-yield submarine-launched missile that is a key feature of the Trump Administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, are supposedly aimed at “enhancing deterrence,” justified as indicating to the Russians that if they use low-yield weapons, we can respond in kind. But these weapons appear to fulfill the function of conventional weapons in a conventional war, and therefore seem designed to fight, rather than deter, a nuclear war. The ongoing “modernization” (read “replacement”) of the entire US nuclear arsenal that was set in motion by Obama included at least one low-yield bomb. Under Trump, however, the drive to treat nuclear weapons as if they can be used in a conventional battle appears to have gained greater prominence. The most recent Nuclear Posture Review, after all, was co-written by Keith Payne, president of the National Institute for Public Policy, and best known for the dubious notion that “victory or defeat in a nuclear war is possible,” as he wrote in 1980. He added that “such a war may have to be waged to that point; and, the clearer the vision of successful war termination, the more likely war can be waged intelligently at earlier stages.” His directives on the means to win such a war (more weapons, better targeting) are coupled with pious assurances that they are in the interests of maintaining a “credible deterrent.”

Concepts such as dial-a-yield are no less dangerous for being potentially undependable in practice. Thanks to its observance of the (unratified) Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, the United States has not detonated a nuclear bomb since 1992. New warheads, such as those planned by the Trump Administration, are tested by computer simulations that stop short of actually initiating a chain reaction. Phil Coyle, a former director of the Nevada test site in the days when the United States actually detonated nuclear weapons to test them, told me that new, experimental designs could sometimes fail to perform according to plan. “Sometimes, they wouldn’t work. I can remember some series where it took five or six tries to finally get it right, so to speak. If you were expecting a particular yield, you might not get it,” he said, explaining that a new design might on rare occasions produce a yield greater than expected, or less, or no yield at all. Coyle is adamant, however, that all weapons currently in the stockpile are a hundred percent reliable.

But such faith is necessarily based on “virtual” tests, and belief that such simulations adequately reflect the real world is not universally accepted. Referring to the specialists who perform such simulations, Thomas P. Christie, the former director of operational tests and evaluation at the Pentagon, told me, “I’m sure that community has done some great work so far as simulations are concerned, because they can’t test. But, if you can’t test, you can’t verify. I’m very skeptical. All you have to do is get about five percent wrong and you’ve got a real problem.” Such caveats are important, not because they make the case for renewed testing but because nuclear war plans tend to assume a degree of certainty in systems performance, a dangerous misapprehension when everything to do with nuclear war is uncertain.

The same uncertainty holds true of the human element. Blair’s lifetime study of nuclear command and control has convinced him that in a real crisis the system would be “prone to collapse under very little pressure.” This stark conclusion was confirmed on the only occasion when it was put to the test: the terrorist attacks on 9/11, when it failed utterly. According to a detailed exposé by William Arkin and Robert Windrem of NBC News, senior officials found they could not communicate with one another. The commander of NORAD (still a player at that time) moved US nuclear forces to a higher stage of nuclear alert and closed the blast doors at Cheyenne Mountain for the only time since the end of the Cold War. Putin, alarmed by these developments, wanted to call Bush to ask what was going on, but Air Force One, which was running out of gas and looking for a secure place to land, could not receive phone calls. When the plane did land, at Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana, it was parked next to a runway littered with nuclear bombs—STRATCOM had been in the middle of a nuclear exercise when the hijackers hit the first tower and was now, while NORAD increased the level of nuclear alert, canceling the exercise and hurriedly unloading the active nukes from their bombers. Almost none of the senior officials in line to succeed the president followed their assigned procedures for evacuation to secure locations. One who did, Dennis Hastert, who as Speaker of the House was third in line for the presidency, took shelter in a secure bunker in Virginia, out of contact with the rest of the government. The education secretary, Rod Paige, sixteenth in line, who had gone with Bush to Florida, was left there when the president’s party rushed to the plane. He eventually rented a car and drove back to Washington.

Even assuming every component of the system worked according to plan, the idea of initiating a nuclear exchange is obviously irrational in the extreme—a hundred nuclear explosions in and around Moscow? “Would it have made any difference if lots of weapons didn’t go off, or (probably) a lot of missiles didn’t get out of their silos?” Daniel Ellsberg emailed me in response to a query regarding the reliability of the weapons. “A first strike was insane from the start; and a damage-limiting second-strike (which I acknowledge accepting, foolishly, for some years) not really less so.”

Nevertheless, there has clearly been a rational motivation underlying all these elaborate preparations for nuclear war over the years: money. The counterforce option, spawned in the early Sixties by the so-called wizards of Armageddon at the Air Force–funded Rand Corporation (the damage-limiting to which Ellsberg was referring), was enthusiastically endorsed by its patron because it parried a threat to Air Force budgets posed by the Navy’s new submarine-launched missiles. Invulnerable to enemy attack, the subs clearly rendered the Air Force’s land-based missiles and bombers superfluous to deterrence. But the sub-launched missiles were not accurate enough, even in theory, to hit military targets on the other side of the world, whereas the land-based ICBMs supposedly were. When I asked Ellsberg, who worked at Rand for many years, whether he knew of any of its proposals that would have resulted in a cut to the Air Force budget, he said no. That little has changed in our own day is evidenced by the Obama-Trump modernization plan to annually produce eighty new plutonium pits—the core of a nuclear weapon—at a potential overall cost of $42 billion, even though the United States already has 14,000 perfectly usable pits in storage.

Critics of our current nuclear arrangements, while quick to advocate for arms reduction or call for a reduction in executive power, generally accept the fundamental premise of deterrence. Congressman Lieu, for example, despite his sensible suggestions for keeping the president’s finger as far as possible from the button, is wholly in tune with the consensus. “For purposes of mutually assured destruction,” he assured me, “if any country were to launch a nuclear first strike on us, all bets would be off.” Given such assumptions, even among the well intentioned, there seems little chance that the nuclear war machine’s massive apparatus will be dismantled anytime soon. When Kehler testified on the merits of deterrence and “extended deterrence” (threatening to use nukes in support of an ally) at the Senate hearing, no one disagreed.

But one individual who most certainly does disagree is a man who spent a large portion of his life in the heart of the US nuclear machine and rose to command it all. “I spent much of my military career serving the ends of . . . deterrence, as did millions of others,” Lee Butler, who as a four-star general had headed the Strategic Air Command, and its successor STRATCOM, from 1991 to 1994, wrote in a 2015 memoir. “I fervently believed that in the end it was the nuclear forces that I and others commanded and operated that prevented World War III and created the conditions leading to the collapse of the Soviet empire.” But he grew increasingly skeptical about the role of nuclear weapons in maintaining global peace.

I came to a set of deeply unsettling judgments. That from the earliest days of the nuclear era, the risks and consequences of nuclear war have never been properly understood. That the stakes of nuclear war engage not just the survival of the antagonists, but the fate of mankind. That the prospect of shearing away entire societies has no politically, militarily or morally acceptable justification. And therefore, that the threat to use nuclear weapons is indefensible.

In retirement, Butler joined calls for the total abolition of nuclear weapons.

The fundamental fallacy regarding deterrence, he reasoned, lay in the assumption that we know how an enemy would react to a nuclear threat. As he put it in the memoir, “How is it that we subscribe to a strategy that requires near-perfect understanding of enemies from whom we are often deeply alienated and largely isolated?” Furthermore, he pointed out, the whole theory rested on each side having a credible capacity to retaliate to a nuclear first strike with its own devastating counterattack. But the forces required for such a counterstrike can easily be perceived by a suspicious enemy to be deliberately designed to carry out their own first strike. Since nuclear rivals can never concede such an advantage, “new technology is inspired, new nuclear weapons designs and delivery systems roll from production lines. The correlation of forces begins to shift, and the bar of deterrence ratchets higher.”

Interviews with former Soviet military leaders immediately after the Cold War, conducted by the BDM Corporation on a Pentagon contract, confirm that Butler was entirely correct as to their reaction to US nuclear preparations in the name of deterrence. For years, the Soviets told the interviewers, they believed the United States was preparing for a first strike. They therefore prepared to launch a preemptive strike if and when they detected signs of such preparations. Ignorant of Soviet thinking, the United States failed to curb military activities that might have confirmed their suspicions and sparked a preemptive attack.

None of this seems to have made much impression on the current crop of nuclear war planners, as Butler recently pointed out to me. “Over the past decade,” he wrote in an email, “the Air Force has undertaken a concerted effort to resurrect the old deterrence arguments. In the process, they have dredged up all of the deplorable straw men to knock down the case for arms control/abolition.” This effort, he lamented, has been largely successful: “Arms control is now relegated to the back burner with hardly a flicker of heat, while current agreements are violated helter-skelter.

“Sad, sad times for the nation and the world,” he concluded bleakly, “as the bar of civilization is ratcheted back to the perilous era we just escaped by some combination of skill, luck, and divine intervention.”