The few white boys in our town could ball. Breakaway layups, nothing-but-the-bottom-of-the-net free throws, buzzer-beater fadeaways. They slept with basketballs in their beds and told us about their dreams. We tried not to stare at the diamond studs in their ears as they talked about winning imaginary games in overtime or seeing blurry scoreboards. It don’t matter if I can see the score anyway, I finna play my hardest regardless, Brent Zalesky said once, squinting his eyes in the sunlight. Brent Zalesky lived in the Crest. He didn’t flinch at the sound of gunshots, he received detentions weekly, and he ganked tapes and CDs from Wherehouse with the clunky security devices still attached. Brent Zalesky knew how to get them off, armed only with pliers and a Bic lighter. This was 1996, and he never got caught. He took music requests and we’d find surprises in our lockers at school. We loved him for this. We loved his buzzed blond hair, his stainless–steel chain necklace, his jawline, his position. Brent Zalesky played point guard. All the boys on the team respected him. They called him Z.

When the boys got their basketball photos from Lifetouch, we collected them like baseball cards and kept them in hole-punched plastic sleeves in our day planners. Each year, Z’s wallet-size basketball pic slid into the front of our collections. Freshman year, he simply signed his name on the back: Peace, Brent. Junior year, he wrote more words on the one he gave Marorie Balancio: Sup Rorie, I think you’re hella fine. Peace, Brent.

Back then there were two movie theaters in town and he took her to the one that didn’t smell like Black & Milds and piss. Marorie said he drove up with a cigarette tucked behind his right ear, but he didn’t light it until after he dropped her off at home. She saw the small spark hanging outside his car window because he had waited until she unlocked the front door. Marorie couldn’t help but look back and wave before she walked inside. Earlier, during the movie, Brent Zalesky had fed her popcorn. She said it was like he knew exactly how much she needed and when she needed more in her mouth. We could only imagine what it felt like, to have his fingers so close to our open lips.

Our parents said no boyfriends until we were thirty. They didn’t talk to our brothers like this because they wanted to bend down and kiss all their titis every day. Sons got brand-new Honda Preludes on their sixteenth birthdays. Our moms took wannabe directors to Circuit City and bought camcorders that ended up in corners collecting dust. Wannabe rock stars got Fender Stratocasters and we felt like those street performers in the city who stand on overturned milk crates and hope for quarters in an open guitar case. Still, we sang a cappella by our lockers on breaks. We wanted to be En Vogue, Xscape, TLC, SWV. Anytime Brent Zalesky walked by we got so weak in the knees we could hardly speak, you know? We wondered if we’d still know him when we turned eighteen, all of us desperate for him in our cotillions. Rosyl Manalo’s mom said throwing a cotillion would be a waste of money, but she also bought a big-ass Louis Vuitton hobo and filed a police report like it was a missing person when it got stolen from her shopping cart at the Canned Food Grocery Outlet. I had never seen her cry so hard before, Rosyl told us, not even when she thought someone kidnapped me at Service Merchandise.

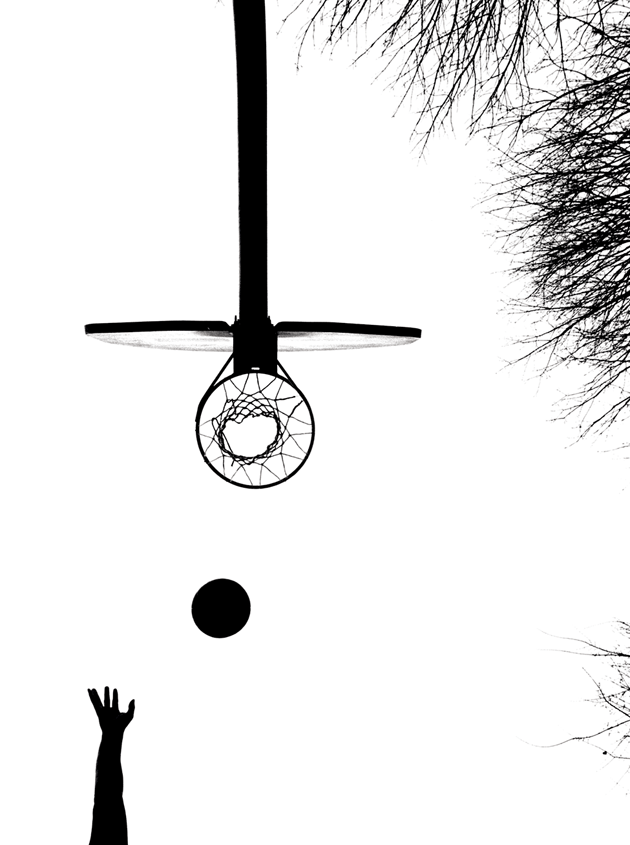

“The Altar,” by Robin Layton © The artist. From her book hoop: the american dream, published by powerHouse Books

We weren’t worth much, not as much as sons. Sons never fucked up. Sons never had to pay rent. Marorie’s brother got a girl preggo when he was eighteen and they mooched off her parents for years. His babies are good luck, her mother said, excited about becoming a lola. But vacuuming at night was bad luck, cutting nails at night was bad luck, buying someone shoes was bad luck. If you give shoes as a gift, that person will walk out of your life forever. Moles, the color red, aquariums—all good luck. If something bad is going to happen to you in the house, the goldfish will absorb it.

We’re not sure why we listened to women who pinched our noses in the kitchen when we were kids because we’d be so maganda if only our noses weren’t so flat and our skin wasn’t so dark. The complexion of the poor people who work in the province. We envied Lianni Benitez because her mother was dead. Still, it was ingrained in us all, to listen to our elders without question, to read their minds, to fetch things they pointed at with their chins. We barely knew our lolas and lolos, but every time we saw them, no matter how old we were, we reflexively reached out for the backs of their wrinkled hands to touch to our foreheads in greeting. Bless, bless, they would say. For all we know they could have been assholes when they were younger, but it didn’t matter. They had white hair now. We had to obey them, no questions asked. Jason Lagundi showed up in a limo to take Rosyl to prom, and then her mother grounded her. She wouldn’t have done that if it had been a white boy from Blackhawk, the kind who’d grow up to rock Brooks Brothers or Nantucket Reds from Murray’s Toggery Shop, the kind who never liked working or practice because he never had to, didn’t you know he was the kind who deserved everything? The kind who’d marry you only if you looked good on paper, the kind who apologized for sweating while he “made love” to you, the kind who wouldn’t still eat you out after getting his lip busted in a fight because, well, he’d never thrown a punch in his life. These boys lived across the Benicia–Martinez Bridge and then some, far enough away to look better, even though they sagged their pants and wore backward caps. They thought they could wear Vallejo, you know, like it was a high school phase. They’d wear it and take it off when it was time to grow up.

When you grow up, you should be a doctor. Did you know your lolo was a doctor in the Philippines?

When you grow up, you should be a lawyer. You can make a lot of money and buy a big house. Did you know I had a big house in Quezon City?

It was always about the house. Lianni Benitez lived in an apartment, and they talked about it like it was a shame. Anyone with a four-bedroom in Glen Cove was automatically a good person. They shook their heads when we told them where Brent Zalesky lived.

He’s not going to go anywhere, our mothers said.

Our lolas echoed them with, What, you think he’s going to grow up to be a professional player, like on the TV?

We didn’t have an answer for that. What we knew was that Brent Zalesky played like it mattered. Real game or scrimmage, there was no difference. What we knew was that Brent Zalesky wasn’t afraid to fight for his team, for our school, for us. What we knew was that he liked reading about all kinds of professional athletes for inspiration. He would talk to us about real-life things in the hallway. Did you know Wayne Gretzky used to eat dinner with his skates on when he was a kid? Did you know Roberto Clemente used to stay late after practice and do one-hop throws into an overturned trash can at home plate over and over again, because it was the hardest throw to make from his position? To Brent Zalesky, there was never a point where great athletes stopped working at being great. No buzzers, no finish lines. They couldn’t rely on luck. They were always playing the game, working harder, trying to be better.

We tried to relay this to our parents. To them, it didn’t matter that Brent Zalesky threw his heart out on the court for his teammates, night after night during the season. They couldn’t admire how he made fast decisions, how he’d casually throw up fingers to call a play as he dribbled past the half-court line, how teammates leaned closer to him during a time-out, how he lifted off the floor in the paint and floated in midair. It didn’t matter that he weaved and shot and fought for wins in a good-for-nothing gym in front of people like us.

In the middle of junior year, Brent Zalesky started dating Marorie. We covered for her and never told her parents where she really was. After dinner one night, he pulled her into his bedroom by curling one finger around a belt loop on her jeans. There was more desire in that move than anything I’ve ever felt in my whole life, she still insists.

He had one chick poster in his room, just one mixed in with his favorite athletes. Marorie was expecting to see a blonde (her mother had a pedestal for a co-worker named Virginia. My blond friend Virginia . . . Virginia and I did lunch today, did you know that she’s white?) but Jocelyn’s hair was dark, like ours, only highlighted in ways we weren’t allowed to think about. Some of us straight-up had mustaches, but our mothers never said anything, as if the longer we stayed furry, the longer they could keep the leashes on. Don’t wear lipstick, our mothers said, lipstick will make your lips turn brown and you don’t want them to be brown. This brown girl on the poster? She didn’t have a mustache.

Who’s Jocelyn Enriquez, Marorie asked.

You don’t know who this is?

Marorie shook her head. She half expected him to talk about how Jocelyn Enriquez looked because that was the routine. When we wore flannel shirts from Choice, our mothers said we looked like farmers. When we stood up straight, they didn’t like that we looked taller than them. We were too skinny, too fat, our hair was too long, our hair was too short. Gain ten more pounds. They’d force-feed us bowls of mashed potatoes and butter and sigh when the scales never changed. Cut your hair. None of us were just right. And when we did crave arroz caldo from Goldilocks, our parents took us to Red Lobster or Olive Garden instead. Marorie was still looking at Jocelyn Enriquez when Brent Zalesky pulled a pair of headphones from underneath a pillow. He carefully placed them over Marorie’s ears, picked her up, and put her on the bed. These were the days of Walkmans, blank cassette tapes and running to the radio to push record. These were the days of working for what you wanted. No quick downloads, no Insta-anything.

We asked her if they hooked up that night.

No, she said, we just listened to Jocelyn Enriquez music. He was surprised I didn’t know who she was.

That same spring, we started to find Jocelyn Enriquez tapes and CDs in our lockers at school. We knew they were from him. Then Candice Quijano discovered that Jocelyn graduated from Pinole Valley High School, just ten miles away from us, and we got hella excited when we learned Jocelyn was a member of the San Francisco Girls Chorus and had a recording contract by the time she was sixteen. Roberto Clemente was from Puerto Rico. Wayne Gretzky, Canada. And here was Jocelyn, who grew up so close to home. We listened to her voice in our bedrooms at night and turned the volume up a little when we heard a track in Tagalog.

Our parents were ashamed of the language even though they spoke it. We used to joke that they didn’t teach us as kids because they didn’t want us to grow up to have accents like theirs. I don’t have an accent, English was the medium of instruction in the Philippines. But when we listened to that Jocelyn Enriquez song in Tagalog, it sounded beautiful. At the end of the chorus were the words mahal kita. We recognized this because of Brent Zalesky. He had written those two words at the bottom of a note in Marorie’s day planner.

What does that mean? we asked her.

It means I love you, she said.

When we were in our beds that night, we thought about how strange it was, how we never heard our mothers and fathers say those words to us before, mahal kita.

When Marorie tried out for varsity, we joined her even though our parents said it was dangerous. They didn’t want us doing anything outside of the house. We didn’t think we would be any safer staying inside and listening to our mothers criticize us.

You’re going to get hurt, they warned us.

We want to get hurt, we said.

Brent Zalesky came to all of our home games. We played for him. At the free-throw line, we slid our palms on the bottoms of our sneakers before taking the basketball from the ref. Our palms got dirty quick, but it made the ball feel secure in our hands. We bent at the knees and learned how to hunger for that sound, those flicks at the bottom of the net. In practice after school we did suicides until we felt like puking. We did them in our driveways at night too.

Somehow, in practice, we started to talk like the boys. When someone would miss a pass we’d say, Where were you at, playa? When someone shot an air ball, we’d put a fist to our mouths and boo like boys. It wasn’t long before we started to spit into our palms as we lined up to slap hands against opposing teams post-game. Good game, good game, good game, we’d all say. Sometimes we couldn’t hold in the laughs until the line was done.

We blasted music in the gym during warm-ups before home games. Coach let us turn up the music so loud that we could feel the beat on the floor, could feel it in our bodies, our hearts. Who cared that the Bulls dominated back then and that the Dubs were shit. On the court, we felt proud. During games, we took hits and threw elbows like champs. Who cared about girls from Napa who put their fingers in our faces and timed their pregame team chant with ours so you couldn’t hear our voices? Who cared that we would grow up to have all kinds of girls interrupt us, correct us, cut us, talk over us, throw shrimp cocktail at us? Could we blame them? We were brown like their nannies, brown like the big-eyed dirty kids in those Save the Children commercials, brown like hotel housekeepers, brown like nurses who wiped asses, and brown like those Miss Universe runners-up who said things like, You know what, sir, in my twenty-two years of existence, I can say that there is nothing major major I mean problem that I’ve done in my life . . . because I’m very confident with my family, with the love that they are giving to me. So thank you so much that I’m onstage. Thank you, thank you so much!

Fuck.

We were brown like their daddies’ secretaries, brown like the women their daddies beat off to and sometimes left the family for, brown like me love you long time, brown like I need to apologize for offending you, brown like may I take your plate, brown like you think I need your charity, and brown like how can I help you, sir? Back then, we helped ourselves. We dove out of bounds. We broke bones. We didn’t care about sweat-slicked ponytails. Didn’t care about the skinned knees or bruises or scars, didn’t bother with bandages in the mornings before school. We got hard. All the marks on our faces and bodies said, So what, I’m still here.