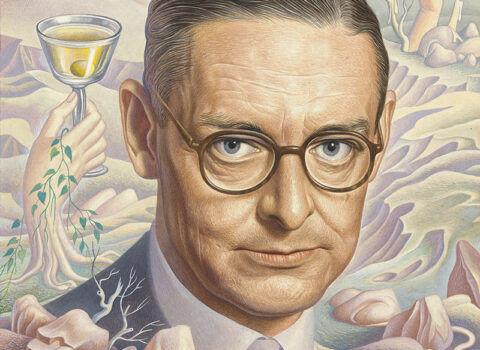

Discussed in this essay:

Anthony Powell: Dancing to the Music of Time, by Hilary Spurling. Knopf. 480 pages. $35.

There are about four hundred named characters in A Dance to the Music of Time, a twelve-novel sequence that Anthony Powell, an English writer who pronounced his last name “Pole,” published between 1951 and 1975. One of the most appealing is Aylmer Conyers, a retired general who’s nearly eighty when, in 1934, Powell’s narrator, Nick Jenkins, meets him at a party. Conyers is an old friend of Jenkins’s grandparents, possibly a distant cousin, and family…