At 4:30 in the afternoon in the Admiral Benbow Inn in Jackson, Mississippi, Jimmy Carter sits opposite a dozen seventeen-year-olds, asking them to help him become president.

“I grow peanuts over in Georgia,” Carter begins softly. “I’m the first child in my daddy’s family who ever had a chance.” His voice is humble yet proud. “I used to get up at four in the morning to pick peanuts, then I’d walk three miles along the railroad track to deliver them. My house had no running water or electricity. . . . But I made it to the US Naval Academy and became a nuclear physicist. . . . Then I came back home to the farm and got interested in community affairs. . . . In 1970, I became governor of Georgia with a campaign that appealed to all people. I reorganized the state government and proved that government could provide love and compassion to all people, black and white—because I believe in it. . . . Now I want to be your president.”

When the meeting is over, Carter, having been introduced to the students before his speech, remembers all their names. The kids are now Carter converts.

Four days after Carter’s session with the students, the former Robert Kennedy aide William vanden Heuvel introduced him to Democratic activists at a Manhattan cocktail party as “someone who has stood with us on the right side in every fight that’s been important to us over the last two decades.” To vanden Heuvel and, apparently, his audience, it didn’t matter that Carter led the stop-McGovern forces at the 1972 Democratic convention; that he has always opposed abortion reform, busing, and, until this year, a federal takeover of welfare; that he favored right-to-work laws; that he supports the death penalty and preventive detention; that he opposed federal aid to bail out New York; or that in 1972 he sponsored a resolution urging all Democratic presidential candidates not to make the Vietnam war an issue. What did matter was Carter’s intoxicating sincerity—as evidenced by the low-key voice, the Kennedy-like grin, and the way he looks you in the eye. What also mattered was that he looked and talked like a winner.

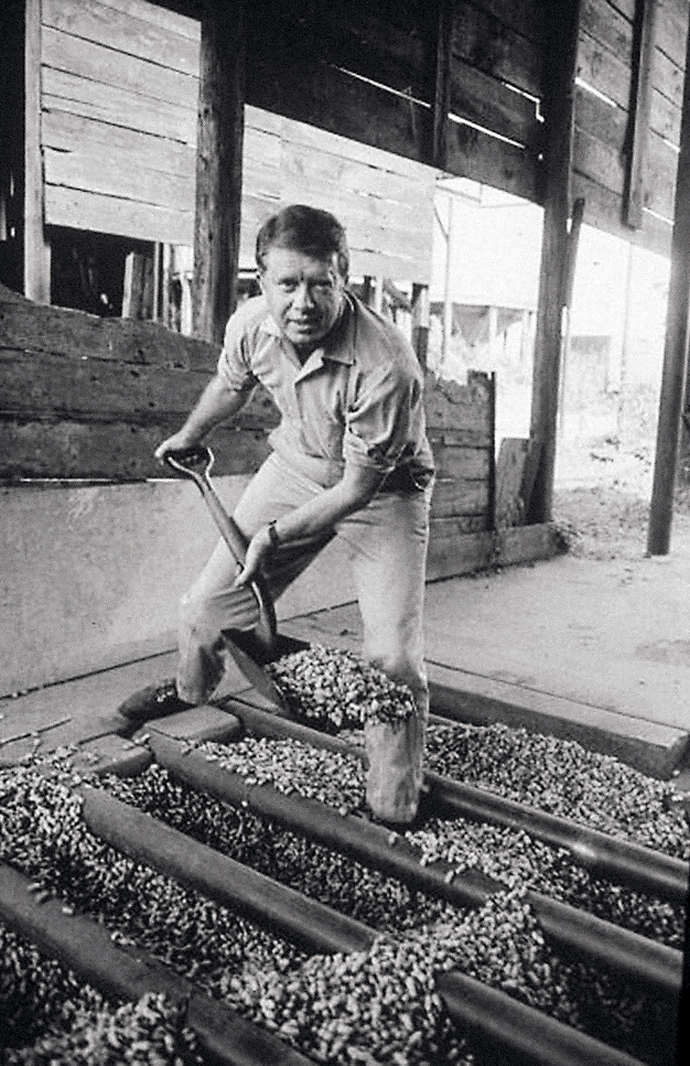

Jimmy Carter shovels peanuts in Georgia, 1970 © Hulton Archive/Getty Ima

The problem with evaluating Carter’s stated positions is that inconsistent statements in his record make it difficult to tell whether he really means what he says. Is the real Carter the candidate who told the voters in Brunswick, Georgia, in 1970, “I was never a liberal; I am and have always been a conservative,” or the one who is now telling adoring audiences, “I’ve always been a liberal on civil rights and social needs”? Is the real Carter the presidential candidate who says the school integration decision and the Civil Rights Act “were the greatest things that ever happened to the South,” or the gubernatorial candidate who denied saying that the Supreme Court school integration decision was “morally and legally correct”?

Jimmy Carter has many qualities that could make him a good president. He has the drive and stamina to take a firm hold of the government. It is arguable, in fact, that his abilities are such that his phony campaign and contradictions should be winked at because he’d make a good president. But in this regard, one of his campaign homilies holds true: “I’ll only be as good a president as I am a candidate,” he says.

The reason he is right is that his campaign expresses his basic flaw. Carter’s friends and enemies agree that, if one thing characterizes Jimmy Carter, it is his obsession with Jimmy Carter. It should be no surprise, then, that Carter sees issues only as props. This is why he couldn’t understand McGovern “using” the war as an issue. And it was natural that, instead of admitting his mistakes or his limited credentials as a one-term governor of Georgia, he’d try to find a shortcut to get to the White House on schedule—that he’d try to blur the history of the 1970 campaign and of his record as governor, and run as the new idol the country yearns for.

From “Jimmy Carter’s Pathetic Lies,” which appeared in the March 1976 issue.