About six years ago, in Iowa, after taking off in a puddle jumper during a tornado, I developed a sudden and debilitating fear of flying. I was seated across the aisle from a large farm boy in military fatigues who giggled with the first violent pitch. “Don’t worry,” he said, to no one in particular. “In these little planes you feel every bump.” Moments later, we were tossing like an aluminum can on an angry sea, and he reached over to grip my hand. I looked into his terrified eyes; his face was pale and glistening with sweat. “MA’AM,” he shouted. “WE ARE GOING TO MAKE IT.”

He was right, we did make it, but on every flight since, I have acutely felt the nothing beneath me. Upon takeoff, intrusive images of the plane exploding cinch my anus tight as a coin purse and inhibit my ability to breathe. A sheer drop feels imminent from even the calmest skies. Because I do not understand aerodynamics, flight is inconceivable. My attempts to research the subject only produce more fear. I feel as though my doubt about the possibility of flight is enough to bring us down, the distance between me and the earth closing on command of thought alone. And how has climate change affected the atmosphere? Can we be sure the old rules are still working?

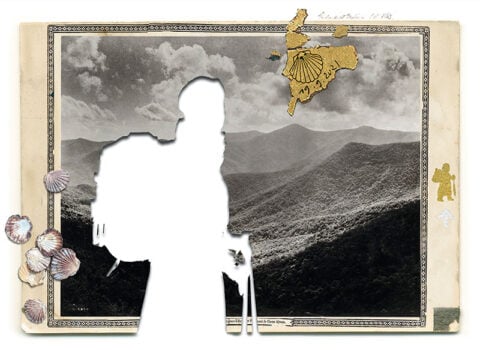

In an Airplane, by Kanae Takeuchi © The artist. Courtesy KOKI ARTS, Tokyo

This is the madness my phobia induces—if you must call it a phobia. While flying, I can’t imagine anything more rational than the spectacular panic skipping through my blood. I don’t understand how anyone on the plane reads or dozes, their faces ghastly in the glow of their tablets. If my fellow passengers gave a moment’s thought to the question of how it is this enormous, leaden contraption transgresses gravity—via what? Some ornate manipulation of ether?—we’d all scream the whole way.

But because my desire to be a reasonable person capable of conducting a normal life exceeds my aversion to flight, I have adopted strategies that allow me to continue taking planes. One useful trick, picked up from the unfortunately named Captain Stacey Chance, creator of the “Fear of Flying Help Course,” is to calibrate my fear against the faces around me, particularly the faces of the flight attendants—faces that are, with rare exception, unperturbed. Another of my tricks is to sit at the window over the wing, as it helps me judge the relative stability of the plane against the horizon during turbulence. Left unchecked by these procedures, the paranoid doom cycle interprets most environmental stimuli as death omens.

“Anxiety may be compared with dizziness,” observed Kierkegaard.

He whose eye happens to look down into the yawning abyss becomes dizzy. But what is the reason for this? It is just as much in his own eye as in the abyss, for suppose he had not looked down.

I have resolved to not look down.

Some months ago, in the C concourse of the Las Vegas airport, I was boarding a flight bound for Seattle when the little door at the end of the jet bridge opened and a mechanic appeared. The man was bald, but for a few pasted strands, and zipped into too-small coveralls, lending him the appearance of a giant muscular baby. As he cut in front of me, I tried to meet his eyes, but they were resolutely downcast. He wobbled toward the cockpit, and in that limbic instant I understood something was off. Then the smell hit me. The man reeked, as if he’d bathed that morning in vodka. Good God, I thought, he’s absolutely smashed.

I believed this man was a death omen, and I wished to narc him out, or else selfishly turn on my heel and get out of there, but I’ve felt the same urgency about a tired-looking pilot (is it possible to fall asleep at the joystick?); about a last-minute change of plane (Rumsfeld logic: Good to avoid the proven malfunction, but what of the new unknown unknowns?); about the overrepresentation of elderly passengers on a plane, who have lived long enough, and so curry no favor with an interventionist God. (Conversely, an abundance of small children soothes the nerves.) I did not dare report the mechanic, because I’ve learned the hard way to distrust my own perceptions.

Around when the bell rang indicating our arrival at ten thousand feet, a loud squealing sound unfurled from the front of the plane. Minutes passed. One couldn’t help but notice a lack of activity in the cabin. No flight attendants feeling their way up the tilted aisle, no doors slamming on beverage service carts. The squealing went on unabated. It seemed we were slowing down too soon. Leveling off.

“Hey, folks. From the flight deck. Just want to let you know we’re aware of the sound in the first-class cabin. We’re not sure what’s causing it, but rest assured the plane is . . . uh, fully pressurized . . . and safe to fly.”

The plane began to descend. I remembered my training and looked to my neighbors, their faces alert but otherwise inscrutable. Useless to me. We leveled off again, floating then, slow and low over a vast agricultural patchwork. The body is trained to expect specific experiences in flight, and this combination of altitude and speed was wholly foreign. The seasoned business commuters among us began comparing notes: flights aborted for mechanical issues, for monsoons. But even they, these coolest of customers, appeared to be distressed.

“Hey, folks. Good news and bad news—”

A shriek of feedback.

“For Chrissakes,” a man exclaimed, a few rows back.

Our plane was taking a hard left, as if along the edge of a framing square. The other passengers began looking to one another, and to me, with wide-eyed alarm.

“Sorry about that. The good news is we got the noise to stop. The bad news is, they don’t want us in the air so we’re diverting to Oakland.”

Beyond the scratched acrylic oval dividing my fragile personal biology from impersonal physical law, I could see we were approaching the Sierra Nevada Mountains. At low altitude, they are uncannily beautiful, like set pieces for a model train, like intricately striated cake icing. Only the level of detail is much sharper, almost hyperrealistic, and this strange, plastic realism distorts perspective, like a dolly-zoom used in film to incite disquiet in the viewer. The eye can’t settle. My heart raced the rest of the way.

Forty-five minutes later, I deplaned and made my way to the bathroom, trailing a family of fellow passengers. “That was pilot error!” the man was angrily telling his wife. “That was totally unacceptable.” The wife’s shoulders caved with apparent mortification. “Totally unacceptable,” he repeated. Was this man a pilot himself? I doubted it. Based on the way he roared his displeasure at wife and son, I deduced he was a professional know-it-all, the dais anywhere his feet happened to travel. He went on lecturing them about what the pilot should have done until I lost them in the crush of the food court. To each his own anxiety-management strategy.

I rewarded myself for having returned safely to earth with a box of deep-fried food, and carried it back to the now empty gate. As I chewed, pleasantly doped, I reflected on my desire to continue living. Was this feeling of renewal an intrinsic aftereffect of panic? Perhaps my subconscious arranged for intermittent terror, so I could once again experience the ecstatic flush of resurrection? Then, I saw our captain emerge from the Jetway flanked by several crew. The crew blew by, aloof, but the captain stopped at the desk to address the gate agent, a tiny middle-aged brunette. When she turned from her screen to greet him, he let go of his wheelie bag and threw his arms around her, all but hoisting her into the air, and held her there a long moment, his eyes pinched with emotion.

So it was just as I’d feared. We were very nearly fucked.

I have been meditating on this experience following last year’s horror show of Southwest Airlines Flight 1380, in which a fan blade broke and an engine exploded, sending shrapnel flying, shattering a window, depressurizing the cabin, and sucking a passenger halfway out of the aircraft, killing her. The passenger was Jennifer Riordan, a forty-three-year-old Wells Fargo executive and mother of two from Albuquerque, New Mexico. It’s said that the blunt impact trauma rendered her instantly unconscious, while the rest of the passengers had a full twenty minutes to contemplate their demise. Except they didn’t die. The pilot made a heroic landing in Philadelphia, and no one else was badly injured. Even so, the fulfillment of the nightmare has me in the grip of its portent. It seems to me there is little difference between Riordan’s plane and any other vessel traveling six hundred miles an hour, several miles above the earth. Death, in every case, is mere inches from the living woman.

Watching our captain cling to the gate agent, I’d felt betrayed. I thought we had a bargain. The bargain was: I dispute my every thought and feeling, and in exchange, I am never placed in any actual danger. What meaning, I wondered, should I make of this?

Consider the CEO’s statement, made on behalf of “the Southwest family,” his extension of “deepest sympathies” for the loved ones of “our deceased customer.” For it’s in the false intimacy of the corporate “family,” and the chilly legalese of “deceased customer,” that I begin to locate the greater resonance, the final meaning. Flying, for the most part, is a banal experience, and “customer” among the most banal of words—a word of capital and commerce. The beloved dead are identified on tax forms and homicide reports by that most solemn designation: deceased individual. The poets are dragged out of their garrets to provide more floral polish: the tender bud of youth flowers, withers, ultimately falls away. Or else the bud’s cut short when, as the Slovenes say, the lady with the scythe comes to visit. However you want to dress it up, the only meaning to be made is what I’d feared all along. As one man reporting on Riordan’s death would put it, and bluntly, “Physics is uncompromising.”

Living is the risk the living take, and we know the vessel only travels one direction, though we try hard not to know it. One can spend a whole life talking about death, simply by avoiding the subject. It is a threadbare scrim that divides the shrapnel from the fuselage, the customer from the corpse, my purportedly irrational fear from life’s single guarantee: its terminus. Without that scrim, all is void; one long drop, without a single surface to claw at or reference, as much in our own eyes as in the abyss. But who can resist looking down?