Once, in an exuberant state, feeling filled with the muse, I told another writer: When I write, I know everything. Everything about the characters? she asked. No, I said, everything about the world, the universe. Every. Fucking. Thing. I was being preposterous, of course, but I was also trying to explain the feeling I got, deep inside writing a first draft, that I was listening and receiving, listening some more and receiving, from a place that was far enough away from my daily life, from all of my reading, from everything.

Writers speak to themselves, whispering assurances, forming aesthetic alliances, imagined fellowships with others, with God, with community, with the past, with whatever, trying to sustain the will to continue to imagine, working through aspects of their own personality, gauging the outside culture, all in an attempt to build a scaffolding to hold up the work. Sometimes, writers go out into the world with their ideas—as I’m doing here—and always, at least as I see it, there is some residue of that scaffold-building, framing their ideas as a way to frame and hold up the work they have created, trying their best to build the case for their own creation. Sometimes it works. Other times it proves a detriment. The work is the work, I have often told myself—and it was in that whispery, assuring voice, usually on some lonely afternoon, staring at the keyboard or at the pen and paper. The power of my imagination is enough right now, I said, and I still say, to myself, and, anyway, if the story is strong enough nothing else should matter. It’ll get out there, maybe, in some form, and it will touch someone.

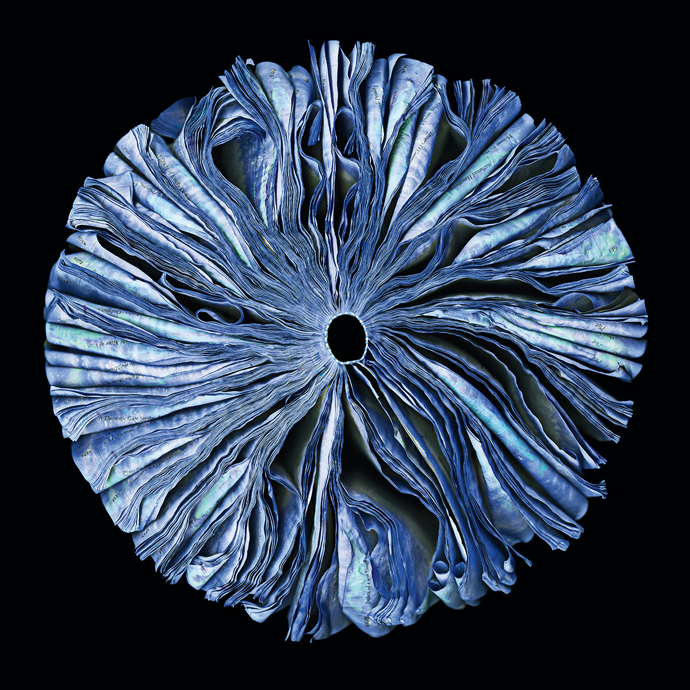

“Bundle,” by Cara Barer © The artist. Courtesy Klompching Gallery, Brooklyn, New York

Flannery O’Connor’s A Prayer Journal, a small book of notes written to herself—beautiful and pious and serious and, yes, sometimes egotistical—carries the sound of a writer whispering to herself, and to me, that she has to live up to the obligations of the work itself. “I want very much to succeed in the world with what I want to do,” she tells God. In one entry, she says, “But I do not mean to be clever although I do mean to be clever on 2nd thought and like to be clever & want to be considered so.” Here is a writer whispering to her God and to herself, expressing the paradox of the inner creative voice, of someone who wants complete candor and honesty in her work but also longs, somehow, to be seen, to be read, to be thought clever. Later, she says to God, “How hard it is to keep any one intention[,] any one attitude toward a piece of work[,] any one tone[,] any one anything.” The profound, destabilizing nature of trying to be creative, keeping one foot inside your own faith, personality, beliefs, political concerns, and identity while the other foot, or perhaps I should say the writing hand, ranges wide and far, beyond the self, into the imagined world where anything and everything can and must happen. How else did this devout soul create the Misfit, the monster whose gunshots in the tree line destroy an entire family one by one? How else—except by writing through faith and doubt—could she imagine her way into the Misfit and his perversely profound comment, “She would of been a good woman if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life”?

Years ago, a fellow writer and I sat across from each other at a table, and a vibration seemed to pass between us—perhaps I just imagined it—of mutual exhaustion and anticipation. With his wonderfully antic and expansive, visionary and humane tales, he had established an eminent place for himself in the literary world. I was known, too, as a short-story writer, but not widely. Between us—and we only sat a short while that morning, sipping coffee—the weird, unspoken vibration continued until I said, nervously, something about my unfinished novel. “I’m trying to write a novel,” I might’ve said, or, “I feel the pressure of the novel,” and he said, “I’m doing the same,” or, “I feel the same.” It was heartening to hear a fellow writer speak of the pressure to write in a longer form. It’s a feeling Alice Munro expressed in one of her rare interviews, admitting that even with all her accolades she still felt, on occasion, guilty about not having written a proper novel.

Over the years I struck up a written correspondence with Don DeLillo, a writer I greatly admire, someone who has written many of the best sentences of his generation, an elder statesman of the novel form who is admirably relentless in his vision as a writer. I wrote him long letters and I’d be thrilled to get back postcards with just a few words, or sometimes, longer responses. One time, when I wrote him a rambling, self-pitying note bemoaning the fact that I hadn’t yet been able to finish a novel, he wrote one of his characteristically brief but poignantly supportive typed notes that told me, in so many words, that the novel took sustained effort—superhuman focus—and a lot of time before it revealed what it was trying to do. I read between the lines. I was a person with very little time—and mouths to feed—and perhaps I should just keep writing stories. As a story writer I felt myself a member of a collegial order of fellow writers, those who, for the most part, had dedicated their lives to the form: Anton Chekhov, my hero; Raymond Carver, another hero in some ways; Munro, the very center, for me, of the possibilities of what the form could do with time; Katherine Mansfield, who carved words into rocklike, pure formations; Lucia Berlin, a more recent hero; Lorrie Moore, who has written a few novels but seems ultimately a pure story writer; Lydia Davis, with her perfect narrative nuggets; Franz Kafka, who wrote a few brilliant yet unfinished novels but had night visions that purified themselves into the story form; Frank O’Connor, who wrote one of my favorites, “The Bridal Night,” a totally neglected story that brings tears to my eyes and charges me with a desire to go in deeper; George Saunders, although if I’m honest about it, envy enters into my regard for him. These writers seemed part of a much larger literary world—and they were—but they were the holdouts, the ones who built reputations on the short-story form, and they kept me company for years as I wrote story after story.

Eventually I wrote a novel about war—about the Vietnam War—in a slightly twisted alternative past as imagined by a slightly twisted young man, Eugene Allen, named in part after my grandfather. The novel was the result of years haunted by the sense of do or die; to become known as a writer, and to do what I had to do as a writer, to fully reveal my creative vision, I must write the novel. But I also felt that I was betraying that part of myself that had assured me that I was first and foremost a short-story writer. I justified my self-betrayal and told myself that by writing a novel I would be drawing some readers to my stories, perhaps at the cost of breaking, for a while at least, my sense of being one with those I loved so much, my fellow story writers.

For ten years, I was an at-home father, alone with my twins while my wife, Genève, worked during the day—starting when they were around one—taking care of them day in and day out, cleaning their faces, changing their clothes, feeding them, playing on the floor, braiding hair, combing hair, taking them on playdates. I’ve kept this part of my life to myself until now—hours at the playground, with other parents, often all mothers, and, later, picking the twins up from school.

Those years, I taught at a community college at night. I remember one class, in Haverstraw, New York: English as a Second Language; working folks who cared deeply about becoming educated and read with devout attention and good humor. I taught them Samuel Beckett: We read Krapp’s Last Tape and watched a film version. They connected with it. At the end of the semester, they pooled resources and bought me a gift certificate to the local mall. We wept together. Year in and year out, I taught classes on everything but creative writing: literature by women, one semester; another, modern fiction. One student, a Vietnam vet—chopper gunner—became a nurse and now works in White Plains. Another, then a teenage mother, became a school administrator in Westchester.

Being a caregiver and a community college professor taught me the humility necessary to continue; it taught me to focus on the duty, on the crayon marks, on the lunches that needed to be packed, on the doctor’s appointments made, on the needs of working people. Hour after hour of caring for children, living vicariously (in a dangerous way) through their successes and failures, was costly and sometimes terrifyingly lonely, but it was also gratifying. I felt a part of a large network of mostly women who cared for one another, who sustained one another—trading tidbits of advice, gossip, spotting one another when there was an emergency, negotiating playdates, going on school trips.

Those days fed into my work. Quietly, to myself, I said, the river that feeds the stories has the same source; the lives of my characters come from the same energy: they too once waddled around a playground, or were held, or not held, as they cried to sleep, and they have been betrayed somehow, damaged, torn up along the way. But the creative aspect, the confrontation with the primal nature of caring for children—and twins at that—taught me, again, the humility and grace of giving in to time itself. Once, I read in a childcare book that the love you give your babies will eventually come back in the end, and I took that to heart because it applies to creative work, to the stories. You might not see it, though.

In one of his stories, “August 25, 1983,” Borges describes a character named Borges signing in at a hotel and noticing that he has already signed in, that another character—himself—has been there ahead of him, not a doppelgänger—that would be uncharacteristically simple—but a form of himself in the future. I’ve had this feeling upon finishing a story; that some other Means was ahead of me, checking in to the hotel, writing a story, and handing it over to me with my own name on the title page. With the novel, I didn’t feel that sensation: with the novel the person on the title page was the person who wrote the novel. It was heavy and, in revision, had to be retooled. It was worked piecemeal and couldn’t be held in my brain in its entirety. With a story, I feel I can rotate it like a jeweler staring through a loupe.

“Literati,” by Cara Barer © The artist. Courtesy Klompching Gallery, Brooklyn, New York

I turned to Isaac Babel and Chekhov, James Baldwin, Virginia Woolf, Mansfield, Edgar Allan Poe, Thomas Bernhard, John Edgar Wideman, Kafka, Langston Hughes, Bob Dylan, Thomas Hardy, Tom Waits, Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, and Flannery and Frank O’Connor for inspiration, whispering to myself: You’ve got to go to the source. I read deeply into Native American folklore. I read history. I read poetry. I reread the Bible. I read Abraham Joshua Heschel. I studied Sufi dervish tales. I searched for a sense of form.

These writers, and others, floated and orbited and were part of my whispered reveries, but at the center, I have to say, if I’m going to be completely honest here, was my own vision, my own way of working, and what felt, when things were good, when I had done all of the work and revision, to be a sense that the story was completely true to itself and to my own tradition. That might sound grand—in this self-effacing age of false humility, when nobody is supposed to speak of internal grandness—but when I was working, alongside, in my imagination, my fellow short-story writers—William Trevor, for a few years—I had to feel, somehow, that I could pull it off. I was building a body of work that would be about the violence and isolation and desolation and joy and grief and grace that I had seen, in my own life, in my own way.

I’m revealing a personal physics. But I believe that every good writer has to whisper words of encouragement that, when exposed to the public, would sound delusional. When you diminish the power of the imagination to make visionary work—Woolf creating Septimus Warren Smith, or William Faulkner entering Benjy-time, or Toni Morrison creating Milkman in Song of Solomon—when you question the ability and validity of one soul, any soul, to inhabit honestly created characters, do you diminish, in the public mind, respect for the power of the imagination?

At times, I heard a critical voice that said, Who are you to write about two homeless men on the shore of Lake Superior scratching a lottery ticket? Have you been homeless? What do you know? And I wanted to counter by saying: no, but I’ve been on the shore of Superior, alone, and I have family members who have been homeless, and I’ve dragged garbage bags of clothing from one halfway house to another, and I’ve felt the sorrow involved.

If readers thought my stories too dark, or too violent, then I would reply, quietly, in that assuring voice that only I could hear: What country do you live in? Have you ever had a sister like mine? Or a brother? Have you seen people destroyed? Have you watched a dying uncle smoke a cigarette in the hospital, twisting off the oxygen cylinder with the Seattle gloom outside, the cancer eating his gay beatnik lungs? Have you sat for lunch in the East Village with a friend dying of AIDS, and listened to him laugh at death and then, in a rage, shout at someone who was staring, I’ve got AIDS, motherfucker? Have you prayed in a small Irish church, some ruins in Cork, with the sky overhead?

But here’s the thing, the twist. If I say publicly what I whisper to myself, as I’ve done here, I actually diminish something, lose something, not only as a writer but as a reader. The writer’s duty is to instruct, first oneself, and in turn the reader, how to envision the vision: suddenly we’re near Johnstown, Pennsylvania, up in the foothills, walking the grassy berm that was once a part of the dam that, when it broke, caused a catastrophic flood; we’re there with someone else, another character, and we’re going through what is now a national park, looking down into the bowl-shaped valley filled with weeds and full-grown trees where the water once sat on a rainy night, May 1889, waiting to plunge the fourteen miles down the valley toward the town. We imagine this couple, on a sunny summer day, with the sound of cicadas in the trees, and we spell it out for ourselves—and our readers—and a story begins to unfold. As long as there are exactly enough words, in the right tone, and as long as there is some kind of active movement, the reader fills the rest. The reader sees it all. It is the reader’s valley, the reader’s trees, the reader’s berm.

Each story is born of a completely different admixture, a combination of my dream life at the moment, my concerns, and the demands of the story itself, not only the characters in a particular situation, but also the internal structure and language and voice. Sometimes I’ll carry a draft around for months, maybe even, in some cases, years, and go back to it again and again, not only with revisions but also just looking at it, holding it, and this process is—and this is something I whisper to myself—expensive. What I do, I say, is extremely expensive. Working this way, using up so much time for such a small form, is costly, I say to myself. This might be one of those grand things a writer whispers, but I think, when I think of my colleagues in the form—Babel riding with the Red Cavalry and suffering death at the hands of Stalin’s thugs; Chekhov writing story after story as he supported his extended family; Munro up there in Canada, at her desk by the window, waiting and waiting and listening and then revising—that the cost of the form is part of its appeal. Munro wrote her first several books in the busy confines of her life as a mother, catching stories and bits of time the way I did. Grace Paley wrote amid her political activism, a busy life in the streets of New York. You can feel it around a story writer’s creations; these small missives of narrative with a void around them, the empty space at the end of the story and the infinite space before the first words appear: the sense that each short story was created out of an impulse much stronger, sharper, more intense than the drawn-out impulse behind a novel.

Years ago, I wrote down, on a sheet of paper that has since been tacked to my work-space wall, an artist credo of sorts, ideas on how I should work, commands to myself that, from time to time, I refer to when I’m in despair, or stuck. Most of these I keep to myself with all the selfishness that seems necessary to protect my own artistic spirit. One aspect of being a writer that is seldom discussed in these openmouthed days, that might look shameful, is that a writer, any good writer, does indeed have what seem to be trade secrets that help sustain the hard work. In his essay “A Word to the Wise Guy,” Burroughs, coming off a gig teaching creative writing, asked, “And am I being punished by the Muses for impiety and gross indiscretion in revealing the secrets to a totally unreceptive audience?”

Burroughs’s fear—as he was suffering a post-teaching writer’s block—is revelatory, not only because, yes, most writers are aware of the Muses, of the submerged, often delicate source of inspiration, but because they are also aware—or should be if they aren’t—that when they give out their tips on how writing works, grant interviews about their own process, they are usually doing so to a somewhat unreceptive audience. There’s only a limited supply of writers who might understand, or find useful, your own process, and some things should be held as secrets because, most likely, they are unique to your own sense of how things work.

How did you make all those leaps in a single story? Where do you get your ideas? What ideas, I say. An idea isn’t a story. A blind man leaning into a cane on a busy street, looking forlorn as he waits for traffic to abate. The side of a supertanker docked in Cleveland in the hot sun, once a proud seaworthy vessel, now a ragtag museum. A white man confronting a homeless African-American man in a train station somewhere between Chicago and Detroit. A baby clutching life in the ICU. (I’ve seen all of these things.)

Truth is, for about ten years, I never once looked at that list of credos. But it was there on the wall.

When I was in college my father sent me Thomas Merton’s Seeds of Contemplation. One of the best bits of advice came from a section titled “Integrity”:

Many poets are not poets for the same reason that many religious men are not saints: they never succeed in being themselves. They never get around to being the particular poet or the particular monk they are intended to be by God. They never become the man or the artist who is called for by all the circumstances of their individual lives. They waste their years in vain efforts to be some other poet, some other saint. . . . They wear out their minds and bodies in a hopeless endeavor to have somebody else’s experiences or write somebody else’s poems. . . . Hurry ruins saints as well as artists. They want quick success and they are in such haste to get it that they cannot take time to be true to themselves. And when the madness is upon them they argue that their very haste is a species of integrity.

You must become receptive to the imagination—call it the muse, call it inspiration, call it the artist within, it doesn’t matter. It might take time. It might take years. If you’re honest, it might never happen.

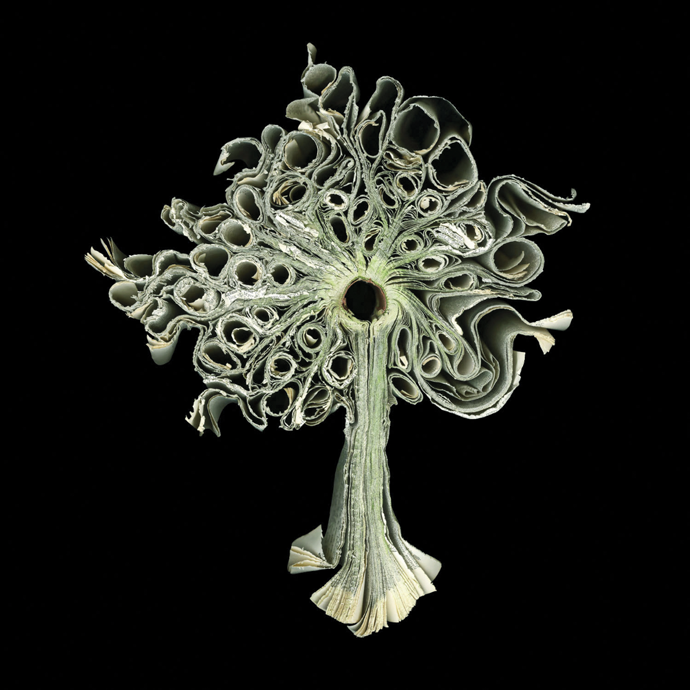

“The Word Tree,” by Cara Barer © The artist. Courtesy Klompching Gallery, Brooklyn, New York

One of my credos is to let a story take as long as it needs to take, as many revisions as it needs, even if it takes a hundred, even if it takes forever, and I think this is a good one to abide by if you’re doing something in a form that is relentless, that can fail with just one wrong move, that, like poetry, is limited in some strange way by its own structure and shape, by the nature—for lack of a proper word—of the infinite open space around it. Grandly, with ego, I sometimes honor myself—no one else will do it—for keeping a story at bay, for letting it sit, lonely and abandoned in a file, a physical file, while I move on and my subconscious does the work. Hemingway had that practice of holding off on a piece, stopping in the middle of a good line until the next day, and perhaps it is a little bit like that, except lasting months. The writer who best described this was Andre Dubus, who, in a late essay, called his new way of writing “vertical writing”; he wrote down into the story—he claimed—and followed the character “home.” He put aside writing horizontally, from point A to B, and began, he said, to go down into it vertically.

Literary form is often misunderstood. The form of something is created within the work, as part of the process, and you discover it as you write. A quote that I’ve lived with for a long time comes from Gerhard Richter, an artist I admire because he works both in abstraction and in what might be called photo-realism. He moves between two completely different modes and in doing so proves a point: an artist can work in many voices—the fucked-up junkie or lost hobo in the Depression and the lonely widow in her mansion along the Hudson River. You can go anywhere. Richter, in a New York Times interview, said something that I broke up into a found poem:

What I Learned from Gerhard Richter

Form is all we have

to help us cope

with fundamentally chaotic

facts and assaults.

Formulating something

is a great start.

I trust form,

trust my feeling

or capacity

to find the right form

for something.

Even if that is only by being

well organized.

That too is form.

The organizing principle around a story, the container that creates the form, is the limitation, the open space at the beginning and at the end; the sense that the entire thing must take a form—the text—with eternal open space before and afterward. Everything must resonate within this space. That’s what I say to myself, at least, when I’m trying to revise, to find a way to make something work. The best you can do is to organize—and this includes the lyrical resonance of the language and images—inside the limited space as best you can—I whisper to myself—and cut it off, end the thing, in a way that resonates out toward both sides of the story.

Even to me this sounds like mumbo jumbo, but that’s the kind of thinking that goes on when you’re creating something. At some point you’ve got to commit yourself totally to the reality of the form, to the inherent limitations, cut the line to let the fish swim away forever. Beckett once said, “The only fertile research is excavatory, immersive, a contraction of the spirit, a descent.” That’s a quote I live with. To plan ahead is not the way to go, I think, and that includes research. I’d rather go into the story and then, later, backtrack and find the facts to correct, or to leave alone.

“Fail better,” Beckett also said. Sometimes I’m not so sure that’s helpful for younger writers to hear. Find an edge where you feel you have succeeded, might be better advice to the beginner. But know that it’s a fake edge, something that you, too, created. On the other hand, Beckett is right.

I believe in the functionality, the pull, the yearning, the force of narrative. It can be small, fragmented, but it has to pull. Inside Maggie Nelson’s wonderfully explorative book The Argonauts are many stories—and just when we grow tired of the academic, of the analytic, we are pulled back into story: Is she going to have a baby? What will happen to her when she has a baby?

Protect the fuel pellets, I whisper. Delineate the line between the losses you have suffered, the pain, and the narratives that you might find by using them as fuel. Once, years ago, when I went to visit my sister in the state mental hospital, a monstrosity at the time, a huge complex with old towers and ivy-covered brick, I took a video camera, thinking: I’ll record all this and use it somehow. I didn’t. Instead I searched out—swinging a net wide—for stories of the kind of men who hung around her in our youth: brutal young men who keyed into a teenage girl with exploitable instability.

Baldwin, in his essay “The Creative Process”:

Perhaps the primary distinction of the artist is that he must actively cultivate that state which most men, necessarily, must avoid: the state of being alone. That all men are, when the chips are down, alone, is a banality—a banality because it is very frequently stated, but very rarely, on the evidence, believed. . . . The state of being alone is not meant to bring to mind merely a rustic musing beside some silver lake. The aloneness of which I speak is much more like the aloneness of birth or death. It is like the fearful aloneness that one sees in the eyes of someone who is suffering, whom we cannot help. Or it is like the aloneness of love, the force and mystery that so many have extolled and so many have cursed, but which no one has ever understood or ever really been able to control.

We sit at a bar nursing drinks with friends and telling one another stories. Sometimes we go into polemic, but mostly we tell stories. We don’t tell novels, or essays. We speak, we reach out to each other, with stories.

A reader reads and imagines—if instructed properly—a barn and a pig and a spider. These are 90 percent the reader’s barn, her spider, her pig. Years later, reading the book again to her little boy, she sees basically the same barn, the same pig, and the same spider, who happens to be writing words in her web.

By its very nature, if you’re writing a memoir and you aren’t famous, an object of prefabricated interest, you must make yourself interesting to your readers, and often you do so by amplifying the drama of your specific experience (unless your story somehow clicks in with the interest of the larger public, in which case whatever you write will be of momentary concern). Fiction, though, must be interested in itself, must instruct in a precise but unique way on how to see, and must leave room for the reader’s imaginative capacity to rethink after the fact.

Forget education, I whisper. Educational fiction, or what I call edufiction—fiction meant mainly to inform, to act as a kind of travelogue for the middle-class reader—is of use, but only for so long. On the other hand, to go into a fictive dream, into a world I do not know, and to feel fully part of the imaginative experience; to draw from my own sense of parenthood while watching a mother decide the fate of her child; or to be with a woman who is locked into her particular historical moment, ordering her boy out of the cellar while an insane white woman upstairs calls for a hot-water bottle—I’ll take it. Give me anything but a sense that I’m being educated.

I’m not sure that teaching empathy is the project of fiction, either. Does it put the cart ahead of the horse to say it is so? An uncompassionate person reading Kafka would simply give up. One is under no obligation to read the work. One has no obligation to work through To the Lighthouse, or Corregidora, or The Brothers Karamazov. The compassionate reader moves ahead. Certain stories yield to compassion with ease—whereas others move us to the edge, leave us there. Too much is demanded of the reader—moving with the instructions given, having to imagine. Reading, like anything, is a skill. We never stop learning to read—I assure myself, my students. On the other hand, maybe I’m wrong. Perhaps a slightly empathetic young person—with just a twinge of feeling for the Thou—finding the right fiction would be yearned into other text. Maybe I’m totally wrong.

Inherent in all shoptalk about writing, inherent in the questions that are just different ways of asking “How do I get published?” is a sense on the part of the student that there is some magical key, some single, precise bit of advice that will unlock everything. All of those how-to books on writing, all of those seminars, the vast Writing-Industrial Complex stretching from coast to coast. Programs. Festivals. Retreats. The pretense of professionalism: take art, a lonely, abject, incredibly hard thing—a gift in the deeper form, as described by Lewis Hyde, something passed on to other people and not meant as some kind of exchange but meant to be passed forward to someone else—and turn it into a profession, a lineup of résumé-ticking points, from panels to teaching gigs to award juries. Why puncture this dream by questioning it? I whisper to myself.

Many writers I admire—from Saunders to Nelson to Danielle Evans—work, or have worked, inside the Complex, and many writers, myself included, teach creative writing at the undergraduate level. My students at Vassar are testing the waters, not looking for the key that will magically unlock their professional futures. When I’ve read manuscripts submitted for university writing prizes, I’ve often found that many of the undergraduate submissions were stronger than the graduate work. They weren’t as polished, but that’s what made them strong; they lacked the industrial sheen and took greater risks.

Perhaps I’m a type. I like to believe that my work has nothing at all to do with the world of academia, or that of pedagogy, or prompts, and comes out of something—I whisper—much deeper, more profound, and more connected with the lonely, hapless souls, the lost, the weary, the troubled, the fucked-up, the disconnected who, like certain people in my life, didn’t draw a card that said: I’m gonna be in a story, part of some larger product of someone’s process.

The rules that I make, the regulations, are going to emerge out of my own situation, my own needs, and therefore, because they are true within the confines of the work, can never be foreseen, and, man, the voice whispers, if a creative-writing class is anything, it is anticipation of the foibles of future works—advice is, inherently, given ahead of action, even if it seems to be in the context of something already done, as in revision. No, even advice on revisions is still an attempt at prophecy, and the magic of creation is that it takes place within the imagination, unforeseen, a surprise.

We need to bring the word Muse back into the lexicon, to respect the fact that, since antiquity, we have searched for a way to articulate in words what is, essentially, a mystery. Each writer has a particular list of inspirations, and I realize that many also have external voices that accompany them along the path toward creation—and for some the external support might be more necessary. But at the edge of creation, alone at the keyboard, no matter how many voices you have accompanying you, there is that moment, before you begin to hear the story in your head, before you push the key and create the word, when you are alone with your own voice and vision and work. It centers in on your imagination, on what you’re seeing, on what you’re envisioning, and, without it, the magic mimetic thing that fiction does, giving the reader precise instructions on how to see, doesn’t happen. I can attest to this because, years ago, I held my babies in a hospital and looked into their eyes and felt the already-told story of how that feels, the sensation of truth in the moment, and I do know that love is love no matter what boundaries it must cross.