I am called Ingrid and my mother is called Basilia and we left our house [in Guatemala] well. We came sad to look for a new life for my family. One risked life boarding the buses and the train fighting to reach the border. . . . There are persons that treated us well and others bad when they delivered us to the line. There were Mexicans that were telling the police how come the “guatemaltecos” came. I asked god why he had not come because that is my dream to go there.

—Entry (11/16/18) in the guest book of a migrant shelter, Tucson, Arizona

All photographs by the author, for Harper’s Magazine. Morley Point of Entry (P.O.E.), U.S. side, Nogales

i: an introduction to border protection

On February 5, 2019, the president of the United States (a certain Donald Trump) in his State of the Union speech warned of “migrant caravans and accused Mexican cities of busing migrants to the border ‘to bring them up to our country in areas where there is little border protection.’”1 Wishing to see the border for myself, I decided to visit Arizona, where my ignorance of local conditions might save me from prejudgment.

Woman peering in from the Mexican side of the border wall, Nogales, Arizona.

At an hour’s driving distance from Tucson lay the internationally bifurcated town of Nogales, a perfect candidate for Trump’s “border protection.” On Wednesday night, braced by a unanimous resolution of his city council, Mayor Arturo Garino declared that Nogales would sue the federal government if it declined to remove the new coils of razor wire. The newspaper remarked: “Garino said authorities didn’t tell him why more wire was installed.” Maybe they mistook him for a Mexican. When reporters tried to get to the bottom of it, they received their own education: “U.S. Customs and Border Protection and the Department of Defense did not respond to inquiries about why additional wire was installed last weekend.”2 Duly impressed by the latest headline (driver shot after trying to run over cbp officer in nogales3—which is to say that the car coasted into Mexico, where police pulled out the unconscious driver and his cipher of a passenger, after which all sources settled into the easy glow of the no comment), I saw on the Arizona side those bright, precious new-minted coils of razor wire shining in the streetlight as beautifully as if they had been cast from Mexican silver. Sometimes they appeared pure white. They caught the light in such a way that they almost seemed to crackle or vibrate; behind them ran various ugly metal graynesses, with black slats of night between them. I waved at a little boy who was in Mexico, and he waved back. Then I went to chat with some Latinos on my side, three women and a man, who were all leaning in toward the fence at a pale form that pressed toward them from the Mexican side; they must not have intended to visit for long, since none wore jackets. The youngest woman, black-braided, who occupied the narrow white curb at the base of the wall (her companions stood in the street), was shivering and clasping her hands across her belly as she bent toward Mexico; to her left, a single glittering coil of razor wire preened like the fronds of a lordly palm tree, and the stained white base of the wall glistened like dirty snow. I told them that the razor wire disgusted me, and they said they felt the same. Their compañera in Mexico was a fortyish woman with black hair and movie-star eyelashes. Her fingers shone as bright as metal. On her side of the wall I now perceived a smiling black-eyed girl-child who pressed her spread fingers against the wall; in my halting Spanish I asked if I could photograph her, and she nodded, her smile widening until I could not tell whether it was strained.

Now, where were the hordes we were supposed to worry about? The newspaper had alerted me that “a caravan of 1,600 Central American migrants was surrounded Wednesday by Mexican authorities in an old factory a short distance from Texas, where they hoped to seek asylum even as U.S. authorities sent extra law enforcement and soldiers to stop them.”4 But this cold, dark sector was silent.

Then from the port of entry silhouettes were born, a good fifteen or more, importing backpacks and roller bags, hastening up the sidewalk around two sides of a gas station that glowed with eerie blank purity. They were practically running away from Mexico; my fixer proposed that they aspired to catch some night bus. (On such matters he and I speculated, pretending to be journalists.) Then we drove across the border. As usual, the Mexican authorities did not even inspect our documents.

ii: the silent border

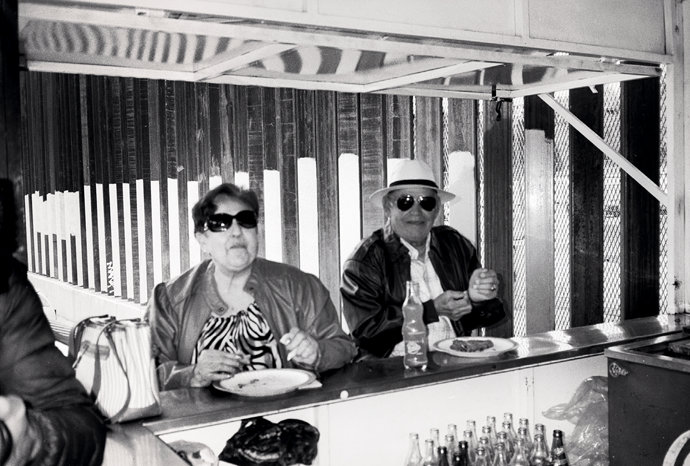

Gloria and Martin de la Rosa, Nogales, Mexico

Yes, it was silent, and so many times I found people falling silent.

“I’ve lived in Tucson for thirty years,” said an immigration lawyer named Rachel Wilson, who lived in a little house with a cactus garden in front. “In the old days it was not a big deal. You could just come and go. Just a minor way of passing through. It was not all these big barriers and all these officers. It wasn’t militarized, not like a war zone.”

“And when did you notice a difference?”

“There were some small changes in the mid-Eighties. The big changes happened in 1996. And then after 9/11 it really changed. We’ve seen that over the years enforcement just gets more harsh. Unfortunately, there’s this perception that it’s all Trump. But things were unbelievably bad even before Trump came into office. Obama was the first to open family detention centers. The good thing about Trump, if there’s anything good about him, is that he has forced us to open our eyes to the horror.”

In 2019 most everyone I met was guarded. (A number of interviewees declined to have their names published. The unvarying cause was worry about retaliation.) At first it seemed like old times back on the Mexican side. I walked down the street until it dead-ended at the rust-red wall, which was perhaps twenty feet high and set in raised concrete, with behind it, both low and high, the precious sheen of that new concertina wire. Nobody was walking in the United States; nothing was happening. Parked cars, empty streets, and clouds ruled over Northside until a white Border Patrol vehicle rolled very slowly by. I sat down on a bench at the bus stop, which was one road-width away from the wall, and listened to the vendors and strolling couples around me. A Mexican policeman drove by; he smiled and waved at me. Now it was time for a taco. The man who made it told me: “I’ve got sixty-five years of selling the tacos right here. I’m the only one who’s allowed to sell tacos right here. A lot of soldiers came recently and put up the razor wire. As a journalist, what do you think about this situation?”

“I am ashamed of my president and ashamed of America,” I replied.

“My opinion is this,” he said, pausing to shake hands with another customer. “These caravans were arranged by Trump and the government of Mexico to get authorization for the wall. These are smoke screens. From here all the way to Texas, it’s a big smoke screen.”

Martin and Gloria de la Rosa were eating their taco breakfast at the stand. They were a friendly couple. Señora de la Rosa said: “I come into Tucson every week. This situation is bad, bad, stupid. This strategy, Trump wants to put pressure.” Her husband wore a white sombrero. He smiled at me when I took their picture, which to my mind gained in local color from the presence of the wall just behind them.

Of course no border patrolmen would go on the record about anything anymore, not even the weather. That was why I asked the fixer, who was sweetly brash, to go and jibberjabber with those individuals, questioning and marveling at everything, while I sat discreetly in the car. For their counterpart, consider the Mexican policeman who proved quite willing to speak to my laptop but not to my recorder; he posed for a picture but covered up his face for fear of local “bad people,” who from context could have been either the very few migrants whom he considered violent and dangerous or the border thugs called “mafias.” I reminded him that the name tag on his chest still showed, so he covered that with his hand.

Concerned about retaliation from judges in the Arizona municipality of Eloy, which will figure at the end of this story, an American lawyer allowed me to quote the following only if its source stayed nameless: “The majority of the cases that I’ve seen in Eloy are simply hopeless. You argue your heart out and you can’t get them out, or you get them out on huge bonds. The Eloy court is just a black hole of justice. The Florence [Arizona] court is more reasonable. I had a client who crossed legally, with a visa. She was the victim of a car accident, and called the police, and was detained and taken to Eloy. They required her to post a fifteen-thousand-dollar bail. The bail bond company put on an ankle monitor she had to pay for for a year and a half. Now she’s a legal resident, but she had to spend a month and a half in detention. Most of the clients I can’t get out. Judges talk about me behind my back. I believe that my fear of retaliation is real.”

Police officer, Nogales, Mexico

And consider the kind old man named Scott who volunteered for a certain faith-based organization in Tucson. He said: “We’ve had just strange kinds of games played that I think are political that ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] has been involved in. Back around the first of this year, we had capacity in our shelters, but ICE wasn’t bringing them; they were dropping them again at the bus station. Because the person who operates our shelter has a close contact at the bus station, they called her and said, ‘We have these fifty people or seventy-five people that have no idea what to do; ICE just dropped them here.’ So our people got organized, went to the bus station, brought the people to the shelters. Our contact talked with her contact at ICE, with whom she has a good relationship, and the person at ICE told her, ‘We were told not to tell you that we were going to drop people at the bus station, or that we even had people to drop.’”5

Descriptions of the most extreme conditions were laid on me by a spokeswoman from No Más Muertes (No More Deaths), a group that deserves all my praise for caching food and water to help migrants in the desert. As you will see, they kept running afoul of the authorities, with ugly consequences, so I can respect their caution. First this young woman instructed me to keep her last name unpublished, because “there’s a lot of interest in our work and I have kids, so . . . ” I asked what precisely worried her, and she said: “I mean, if we’re actually going to go into it, then I’d rather not do a photograph.” So I next agreed to leave my camera in its holster in exchange for the following explanation, such as it was: “I think it’s mostly just that we’re in a really politically divided and heightened time. I believe in the border work that we do, and I just think it’s a reasonable precaution. We’re definitely on the radar of some white-supremacist groups nationally, and I just prefer to . . . We’re a mostly volunteer organization and definitely believe in our mission, and . . . I think it’s useful to focus on the work we do and not specifically on any one member of the organization.” After the interview, she emailed my fixer asking that the “explanation” not be published either. By then I had had enough.6 (Respecting her fears, I will at least refrain from printing her first name and any description.)

iii: samuel and antonia

Let us now meet the migrants themselves. We begin with one quietly cheerful shelter for asylum seekers. Although the Methodists had started it, “We have Unitarians, we have Catholics, we have Presbyterians, Lutherans, and some people who are atheists. I even have a couple of Republicans helping out! They talk to me about the wall but are still here helping out.” In keeping with the regional mood, I was asked not to identify the place (“in the Tucson foothills”), and the co-coordinator who showed me around (she was called Diane) declined to provide her last name, because “we’re just kinda protecting our folks. We don’t want location or names or anything like that, because I worry about protesters.” No location, then, but I will say that planted in the gravel in front of the building stood a sign from that brave organization No More Deaths: humanitarian aid is never a crime—drop the charges, with a hand reaching up for a water jug somewhere between two saguaro cacti.

Diane showed me around. Here was the pantry and the dining space and a room of tightly spaced cots, each with its tucked-in sheets, blanket, and folded towel. On one bed a pair of scissors lay; on another, a little book, perhaps the New Testament; on a third, a child’s dark jacket. And over here and over there rushed that loving woman, one of many good angels, a trifle past middle age, with her sun-damaged skin, her name tag around her neck, and that sweet shining smile, gazing at me with quick-ripening trust, then helping the other volunteers deploy snacks, lunch, and toilet paper from their neatly stacked hoard.

As she told their history, “This past October we had a church up the street, Saint Pius X, get two hundred and fifty asylum seekers. And then they had a big funeral coming up, so they asked churches in the area to take some of those people, and we were one of them. We had twenty-eight asylum seekers. We had people volunteer and bring stuff; it was amazing, and it was really high stress because we didn’t know what we were doing.” After those first migrants had come and gone, “the pastor said this is an ongoing problem.”

The shelter’s adult “guests” had been kindly provided with ankle bracelets by the U.S. government, which had released them to Diane’s organization pending their reception by individual sponsors. Surprised by this humanitarian procedure, I asked the volunteer named Scott why ICE had agreed to it. He said: “They were getting into a bind public-relationswise. What first happened was that ICE was just dropping people at the bus station. People were dropped there with no resources and no idea what to do. And there was a big outcry about this, a lot of publicity about what they were doing; it was just a ridiculous situation. So people from the community started volunteering. There were no shelters; they gave them some money, some food, helped them get a [bus] ticket, helped them understand what would be involved to get going [on their way].

Diane, Tucson, Arizona

“The criteria for people that we get is, number one, they have to have children with them; number two, they have to have passed their initial credible fear screening; number three, they have to not have any criminal record that disqualifies them. Then they have to have a sponsor in the country who will provide them transportation to their location and will guarantee that they will support them economically for whatever period, however many months it is. They are not allowed to work at all. Once that’s done, they are released and brought here, and we help them get in touch with their sponsor, who sends them a bus ticket electronically. Then we get them to the bus station with food and warm clothes and whatever they need. Usually they arrive with just whatever they can carry in a small bag and the clothes on their back, which they may be wearing for weeks or months.

“We got involved about two years ago when ICE made contact with the bishop of the United Methodist Church, Bishop Robert Hoshibata. At that point the decision was made here in Tucson that we would start a couple of shelters.”

When I asked Diane what brought her into this work, she said: “Well, we had a person here in sanctuary for a couple of years. One of the things the pastor talked about is, What would you do for another person? This is kind of my answer to that, to show compassion, I guess, and to make their lives less miserable, because I feel like most of this is the fault of the United States.”

“What do you think about Trump’s wall?”

“I think it’s ridiculous.”

“Why do you think the people who voted for Trump want this wall?”

“My personal opinion is that a lot of them just want a country that has white people, and they’re worried about not being a majority anymore.”

Among the shelter’s inmates was a welder and solar-energy worker named Samuel, twenty-nine years old, a little heavy, smooth-skinned, with a big round face. He smiled when he spoke, sincerely or nervously or meaninglessly, how was I to know? And like so many of these people (to whom their own and others’ sufferings must have been old news), he had a way of making light of whatever he must have endured.

Squinting at me, he began in his high, pleasant voice: “I’m from Honduras, from the Copán ruins. Many trees, very many mountains. Many people. It’s a city with a lot of people.”

“What made you decide to leave home?”

“Much insecurity,” he immediately replied. “There was no future for the kids. There was no work, nothing for them there.”

Samuel, from Honduras

“How many in your family?”

“My wife, my son, and one girl that I left in Honduras.”

“How old is she?”

“Two.”

“Who takes care of her?”

“My wife. I came with just my son, Nelson, and my wife stayed with her.”

When I asked him to describe their family conference, he squinted into space and said: “Well, I had to talk with my wife, and it was pretty obvious that there wasn’t a future for the kids, and we were pretty much in agreement that this would be the best option for them. In my country it’s very normal for people to separate, because everybody comes here; there’s nothing there.”

“Why are the conditions so bad in Honduras, and how long have they been bad?”

“There’s no employment. Times have always been bad in Honduras. As long as I can remember it’s been like that.”

“And why?”

“I don’t know. But back in 20187 there was an election with a lot of voter fraud. It’s always been this way. In Honduras, a president can never be elected twice. When that president took office the first time, he changed the laws so he could be elected again, and everyone said no, we don’t want this.”

But why should this have motivated Samuel’s migration? When I asked Rachel Wilson how she would characterize typical asylum seekers, she replied: “They seem to be mostly women and children coming from Central America, fleeing because of unbearable violence. So if you talk to people, even if the person says to you, ‘I want a better life for my children,’ if you scratch beneath the surface, they’ll say, ‘Well, I can’t make money because I can’t leave the house,’ and if you ask, ‘Why can’t you leave your house?’ they’ll say, ‘Because I was forced to be a gang member’s girlfriend, and when I wanted to leave he didn’t see it that way.’ I think that some migrants over here, they think it sounds more benign to say, ‘Look, I just want a better life.’ I think that some migrants fear that if they say what an awful time they went through, it may seem that they want a handout. The violence now is at unbelievable levels. No one I’ve met from there has said, ‘Oh, yeah, my life has been totally peaceful.’ Everyone has a murdered family member, or they’re threatened with murder.”

None of this apparently fit Samuel’s situation, though I never thought to ask him whether he had faced serious intimidation. Rachel now continued: “The situation in Honduras is slightly different from the one in El Salvador or Guatemala, but the main reason is that, as gangs have taken more and more control of the country, the belief that women are property has taken extreme hold. Someone wants to get out of the relationship, you just kill her. One of my clients, his nephews were killed in front of him because they wouldn’t join. In Honduras there’s a lot of state violence because of the election. Indigenous people are particularly targeted because they’re seen as nonhuman.”

Just across the border, in Nogales, Mexico, another doer of good works named Father Sean Carroll ran his own shelter and migrant-aid center. And he kept an intake survey. His conclusions differed from Rachel’s: “In past years, eighty-eight or eighty-nine percent are migrating from economic need, but this past month, in January, a significant percentage, about sixteen percent, state fear of violence.” But he very possibly lacked the time to, as Rachel had put it, scratch beneath the surface.

So was Samuel “merely” an economic migrant, or had he been threatened? All I can say is: I never got to know much about him.

“How many years have you been married?” I asked.

“Seven years.”

“Once you decided to separate, how was the last day at your house with your wife?”

“Very difficult. With her father, with her kid, it was very complicated.” (You will hear him employ that characterization more than once. It connotes nothing pleasant.)

“Tell us about your journey, from when you first said goodbye until you came here.”

“We left on the twenty-second of January,8 and it was very, very difficult. The route for undocumented people is very complicated.”

“How did you know where to start?”

“Lots of people come here.”

“Did you go to a coyote or did you talk to some friends who came here?”

“No. From Honduras there’s already many caravans.”

“When was the first caravan?”

“I’m not sure. Maybe in the year past. But one just left on the fifteenth.”

“How did you hear about the caravans?”

“A lot of people come on the train. I left alone. I knew that you look for the trains and you try to find the way north, the route that goes to the border. I brought a phone with me, and I was looking at a map to figure out where the border was. Some people go on a bus, some on the train. You have to ask the people.”

“What made you decide not to go on the caravan?”

“When I left Honduras, the caravan had already left.”

“Otherwise would you have taken it?”

“The caravan went to Mexico City, and that’s where they rested before they came up here.”

I asked if he minded missing it.

“Not really,” he replied, smiling a little. “The caravan is a lot of people, and it takes more time.”

“Is it safer?”

“Could be,” he said, spreading his hands.

I asked him to recount the stages of his journey.

“So from Copán we got to Guatemala by bus. We crossed the border from Guatemala into Mexico. We were eleven people who crossed. We crossed through the mountains so that no one could see us, not the police, not the Border Patrol.”

“Who were the other people who crossed with you?”

“We met up on the road with other Hondurans.”

“Did you have any problems in Guatemala?”

“Guatemala, it’s not a problem. You can travel through Guatemala with a Honduran passport.”

“What was it like going through the mountains into Mexico?”

“It was pretty simple. You find someone with a truck, you pay them. A thousand Mexican pesos9 to go three hours. All the eleven people paid, and then we got taken further. I don’t really remember the names of the cities because we were just rolling. They just leave you in the town and you pick up the next one. Pueblo to pueblo, truck to truck.”

“How much did the trip cost?”

“Total, one thousand dollars, from Honduras, for my son and me.”

“What did you think of Mexico?”

“Mexico is very complicated, especially without papers.”

“What was the most scary or dangerous thing that happened to you?”

“The biggest fear is that you get kidnapped” by the criminal groups in Mexico; “then they start to ask you for money from your family. These cartels . . . ”

“And the most dangerous criminal group?”

“Giant cartels. They’re big and scary.”

“Did anything bad or scary happen to you on the trip?”

“So, it was always pretty scary, because you’re always running. Every time you got stopped by the cops, you’re basically pulling out money.”

“Where did you sleep?”

“We always paid for places to stay: basic dormitories. And when we arrived in the center of town, we would encounter people who would offer rooms.”

“What was it like for Nelson?”

He laughed. “Well, to bring kids is very difficult.”

“How old is he?”

“He’s seven.”

“What things did he say to you during the trip?”

“I was telling my son things like we came so you can have a better future for yourself, and we also need to help your mom and your sister back home. My son is very understanding. He would understand all these things. He was pretty chill10 about it. Sometimes he would get hungry, and it was difficult, but he was pretty easygoing.”

So the boy got hungry. Surely Samuel, too, went without. I never thought to ask those two how thirsty they became, because I had not yet been educated by that No More Deaths volunteer, who sometimes cached water for migrants. She said: “As someone in good health who is relatively young, it’s exhausting. For me, when I’m walking, we use GPS, we have established routes, we know where we’re going, and we have experience being in this extreme environment, and it’s still incredibly taxing to put three or four gallons in your backpack and carry two on your person and walk for a period of time until you get to the designated water drop.”

“How often do you find living people or dead people?”

“If you look at the number of recovered remains, it would even out to one every three days. But these numbers don’t actually reflect either the people whose bodies we will never find because they have been scattered or deteriorated, and they also don’t reflect the people that we know to be disappeared. So we have a missing-migrant hotline; so we do know with a certain amount of certainty about the number of people whose family members have been able to place them in this region and then just never heard from them again. The entire map of the Growler Valley, where you see that Trail of Death that has been brought up in court, there were days when our volunteers would be out for a week and they would find ten or eleven sets of remains. When you look to the west of that range and you don’t see as many red dots, it’s only because those are the areas we don’t have access to. It doesn’t mean the people haven’t died there. . . . ”

Meanwhile, all that Samuel had to say about whatever he went through was: “We crossed the river here, outside of Nogales, in the desert, without a coyote, and we got caught by Immigration, and then we came here.” He laughed. “The phone worked in Mexico, but once we got here, it was like, We’re going for it, and we just crossed.”

Which river was it? On Sunday my fixer and I rolled east along the north side of the border wall and did indeed come to a creek that flowed under a gate; a man and boy might have worked their muddy way through there, although I had subsequent questions about the mafias who controlled the southern side. As for getting caught, well, nothing would have been simpler; a white Border Patrol vehicle was idling right up the hill! Farther east flowed the Santa Cruz River. And who was Samuel? At the time, I considered him simply calm, brave, intelligent, and competent. When I said as much he self-deprecatingly replied: “Very complicated to do this.” As I think back on him, he grows ever more cipherlike to me, being someone whose motives, situation, methods, and future I have now considered for a much longer period than I spent with him. What if he had possessed the superhuman, patient openness to answer my questions for a week? Let’s just call his journey very complicated.

Samuel’s ankle bracelet

When I asked what had happened after his capture, he replied simply: “We signed some papers looking for asylum, and so I got an ankle bracelet. I was held in detention for three days with my son. ICE took me here. ICE gave us the bracelet and took us here.”

“What do you think of our President Trump?”

He smiled. “Trump’s talked about in all countries, and he doesn’t like immigrants, but because we have no opportunity in our country we have to come here.”

“So what do you hope for from the United States?”

“I have no idea.”

At my request, he stepped into the sun to be photographed, pulling up his left pants cuff to show my camera that black insignia of humiliation around his ankle.

Next was Antonia, four feet something. Her daughter came up nearly to her chin. In appearance and demeanor as well as height, she could almost have been a schoolgirl. Her smile—was it the fullness of her upcurved lips, baring her imperfect teeth without apparent shame, or the way that her eye corners so plausibly echoed it?—almost misled me into imagining that here was someone who had not yet learned what it was like to suffer. (For what it is worth, the fixer, just then interpreting, who had pronounced her Spanish to be indigenously accented, further volunteered that she was “extremely uneducated.” Why should she have been any different?) Her hair was neatly parted across the top of her head.

“How many people in your family?” I began.

“Me, my daughter, and my husband.” (Not surprisingly—perhaps thanks to ICE—the child feared me.)

“Why did your husband stay behind in Ecuador?”

“He didn’t want to come,” she replied.

“Were you disappointed?”

“Sí,” she said readily.

“You will stay together with him or is it like divorce now?”

“We’re together the same.”

“Can you tell us about your journey?”

“It was beautiful,” she said. I must admit to not expecting that.

“Tell us some of the things that happened.”

“In Mexico City we went to the pyramids, saw the Virgin of Guadalupe, and Coyoacán. There was a really big pretty church.” Once again she reminded me of an ingenuous schoolgirl to whom nothing bad had happened. Therefore, I must have been the ingenuous one who could not read her.

“Did anything bad or scary happen?”

“No fear,” she replied with a big smile. “It was just a really pretty journey.”

“Do you have an ankle bracelet?”

“Yes,” she said. (Of course it resembled Samuel’s. From a distance it could have been some kind of watch.) She asked what it was for—could no one have told her?—then inquired: “When I get to Baltimore, will I be able to work wearing this or not?”

“I don’t know,” said the fixer.

“Why Baltimore?” I asked.

“Because my sister works there.”

I asked where she had crossed and what had happened. She answered: “In Nogales. We came across the border, outside of town, in the desert. There was a wall, and we walked a little bit further, and then the police came. They took us in a car, and they took all our clothes and our backpacks and brought us to a little building.”

And once again, just as with Samuel, I tried and failed to imagine her experience. Where in the desert had it been, where along this lonesome border with the weird lonely ocotillos grasping darkly at nothing, and shadowed saguaros that in that scaleless desert could have been her size or the height of the Washington Monument, then faraway mountains, beautifully clear, and between her, her child, and them, glowing narrow pool-like mysteries that might have been real water or maybe mirages, and somewhere, maybe in sight, detention, rescue, or death? Since from Ecuador across Mexico to Arizona is a pretty long way, had she not perceived what to look out for, wouldn’t she have died? And what had it been like, when Northside’s official hand fell heavily on her shoulder? Suppose that her first tongue was, as it might well have been, a Native American one. As Rachel Wilson reminded me: “It’s a particularly bad problem for indigenous people, because no one on the border speaks their language. Indigenous people usually speak a little Spanish, so they [the cogs in the American legal system] think they understand everything. They’re entitled to an interpreter in court, but they have to ask for it, but if you have to ask for it in your native language and they don’t understand your native language . . . ” The fact that Antonia had been ignorant of the ankle bracelet’s purpose had been troubling if not outright diagnostic.

So I went back to the beginning. I asked her: “What made you decide to leave Ecuador?”

Antonia’s ankle bracelet.

“I worked in the fields with the cows and animals only to eat and buy clothes, nothing more. My husband worked building houses, and sometimes there was work and sometimes there wasn’t work, sometimes no food.” The daughter was eight.

“How was it for her coming across?”

“When we got to Immigration she was afraid and she cried.”

“Did you cross with or without a coyote?”

“Without a coyote.”

“How did you know which way to go?”

“There’s just little roads. They said, ‘There’ll be a wall, look for the wall. Just keep going north and you’ll find the wall.’ We got to the big wall and weren’t able to cross it, so we walked further away and had to walk.”

“How many people were you when you crossed?”

“Just the two of us.”

Again I sensed a disinclination to recount the actual border trespass. As for what happened in custody, as with Samuel and his son, both detainees preferred to pass over it.

“You’ve heard about the freezer?” asked Rachel Wilson. I said no. “The first place migrants are detained is called the freezer. People’s fingers will turn blue. There are instances where children have diarrhea and are throwing up and have no clean clothes. Then they’re moved into the so-called dog cages where they have Mylar blankets; at least they’re not sleeping on bare concrete. Here in Arizona, at least, they’re not in the dog pound part.”11

“Why is the freezer so cold?”

“We can’t get a straight answer from CBP. The A.C.L.U. has been trying to find out.”12

Neither Samuel nor Antonia mentioned the freezer. Every other detainee I interviewed did. In this shelter was a binder of handwritten migrant stories and facing-page translations. Here is what a girl named Maybek wrote on November 16, 2018: “We came in buses and enclosed trucks in which we couldn’t breathe. After [that] they left us in the desert. After six hours there immigration arrested us. And took us to a hidden house and it was very cold. They took our sweaters. Afterward they asked for our data. . . . ” Then came another “hidden house,” where they were kept for three days, then a church called Alverca, then another church. Maybek ended: “My dreams are to learn English and go to school and pursue a career.”

Many entries were sunnier, such as this one: “My name is Alex. First, thank God for all he has done on our trip since we left on the fourth of this month. . . . We were seven days in immigration and on this day they brought us to this church where we can see the world and hope God will bless you always.”

Why not? Those people numbered among the lucky. Because they all had sponsors, their detentions were brief, as were their stays at Diane’s shelter. Most stories I would hear were less pleasant. In other words, border protection works in wondrous ways.

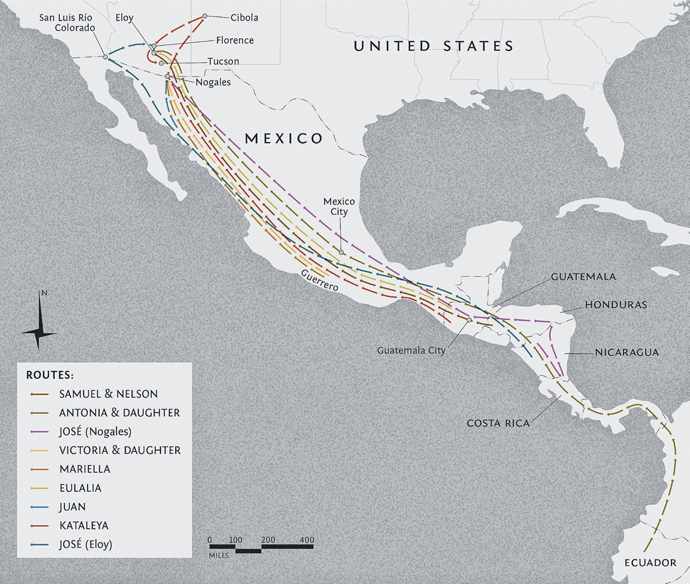

Map by Dolly Holmes

iv: the mafias

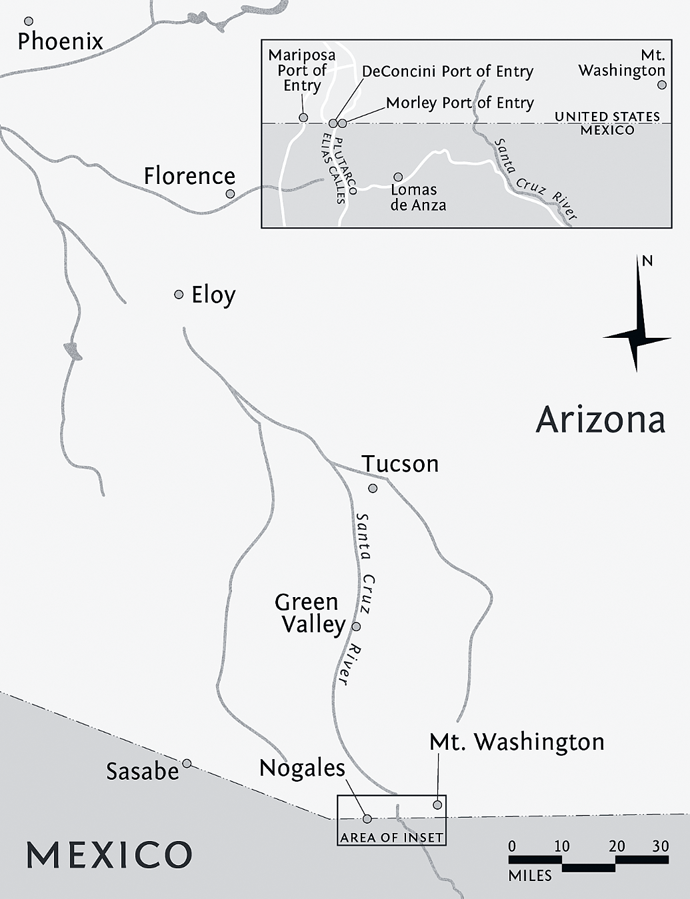

“Just keep going north and you’ll find the wall,” Antonia’s well-wishers had advised her. Then what? “We got to the big wall and weren’t able to cross it, so we walked further away and had to walk.” So that was what she had done, simply pushing on and pushing on, like the Little Engine That Could, until she won the victory, which is to say, the ankle bracelet. But had it really been that easy? First of all, once she encountered the wall, how much further away had she and the child needed to walk? In most such interviews I came to learn that migrants possessed only the sketchiest notions of the localities, roads, and distances that confronted them. But I could not immediately perceive this fact, and so when I got to the Mexican side of Nogales I assumed that either westward or eastward the wall must end in what I thought of as walking distance.

“It goes maybe twenty-five miles,” said the previously introduced Mexican policeman who covered his face. “I believe it’s all wall up that way.”

“What’s the saddest thing you’ve seen?” I asked him.

“We can start from today. I saw a kid who came from Guerrero. He actually had a bullet sticking out of his shin. He was feeding his animals out on the farm, and shooting broke out, and he felt something burning. He went to the hospital, got a letter from the police saying he had no bad record. I just gave him a little advice on what to do, how to stay off the streets. He just went to the shelter.”

“Is it true that the Mexican side of the border is dangerous to both east and west?”

The policeman insisted: “As long as you’re not involved with anything suspicious, you can go anywhere you want.”

But I asked five taxi drivers in a row for a wall cruise, and they all turned me down, citing mafias. It was almost five at night when I got into a taxi and swung down the bumpy road. The driver said that it got dangerous past the next crossing on account of mafias. We were headed west. He said it was worse to the east. Before I knew it, we had passed the renowned Motel Miami, whose restaurant boasted tv color; next came a sandstone cliff with the wall on top of it, a declamation of palestinia libre boicott israel, and a handwritten sign for a car wash, and we ascended the hill that followed the wall. Two pretty girls leaned against a white car as the gray sky began to darken. The wall blocked off the back yards of many tiny houses. By now, Nogales’s Arizona incarnation had ended; through the border slats I saw nothing but grass and brush. That was my America right there: pastel greenish-brown of grass furring the rolling hills. Finally we glimpsed a white Border Patrol car with its lights on. And the wall continued, jigjagging up a dry hill, with the driver now worrying about the bad part, for we had nearly reached the Mariposa Port of Entry, which he described as “the big one where the trucks are, then it gets dangerous.”

“What would happen?” I inquired.

“Many things,” he said sullenly.

Creeping down the hill into Colonia Reforma, we turned right and left, achieving a place where the local wall was sheet metal and the American wall was out of sight. Here came a graveyard, dry and crowded with tombs.

The driver kept crabbing about how dangerous it was, so I told him to find me a mafia princess.

“There are definitely princesses here. Mafia princesses, I’m not sure.”

There by Taquería La Niña was the Mariposa crossing. I saw a sign pointing toward Hermosillo and a long line of America-aimed cars on one lane of the curving, otherwise empty road. That was as far as he cared to go.

“See that white truck right there?” he said. “That could be a mafia truck.”

“What makes you think so?”

He would not answer, leaving me ignorant and skeptical.

“I can drop you here if you want to take pictures,” he eventually allowed. “Even if you were shot I would wait for you.”

“But if I got shot, how would you get paid?” He frowned at that.

So I got out, leaving my laptop on the back seat, and (thanks to some recent abdominal surgery) crept rather than scrambled up onto a reddish berm of sand, where I found myself amid a line of old trucks, all of them with dark-tinted windows, looking down on the border station. As I wandered forward, meaning to photograph this dreary vista, just beyond the trucks, low, weed-grown hummocks of garbage and broken concrete marked the edge of my vantage point, and then, considerably below, that narrow-looking black ribbon of border wall ran straighter and smoother than usual, behind which lay some sort of enclosed park for white vehicles (belonging, I would guess, to the Border Patrol). Then came an immense rectangular bureaucratic edifice whose roof sloped up away from Mexico. Just rightward of this stretched the many tunnel lanes of the actual port of entry, with traffic backed up as usual. Directly in line with the latter, on a nearby Mexican hill, rose a corrugated-roofed shrine: Between two concrete pillars, the Virgin of Guadalupe clasped her hands. A long rosary streamed down from her wrists, and a tilted cross stood knee-high before her. Flowers grew from a plastic bucket beside her, and a baseball cap lay at her feet. Raising my camera, I twice tripped the shutter, and from inside the truck on my immediate left came the soft wails of women and children. I believe with all my heart, but of course cannot prove, that I was hearing would-be migrants waiting for darkness to be sent over or around the wall, whose termination some people in town had said was another two or three miles from Mariposa, although others claimed it ran much farther to the west. I had been hoping to see a spot where Antonia, Samuel, and their children had crossed without help, but since the driver had reached his limit, and the prickling at the back of my neck advised me to get out of there immediately before some mafia or other penalized me for disrupting business, I retreated down the berm.

Nothing like this had ever happened to me along the California-Mexico border. To be sure, even there were places that it was inadvisable to go at night, but never any twenty-four-hour no-go zones. Mentioning this fact to the driver, I asked: “No one was ever afraid there, so what’s so different here?”

American side of the wall, east of Morley P.O.E.

“I’ve never been there,” he predictably replied. “I’m from here.”

Again and again on the way back he insisted on the mafia border menace.

“What do you think of Trump?” I asked him.

He laughed. “I don’t know.”

“I hate Trump,” I said, “but all these things you say about the border, they sound like what Trump says. He goes on about cartels. . . . ”

As usual, the driver would not answer.

We began to drive back down along that snaky rust-red monster of wall. I had him stop from time to time so that I could take more notes and photographs. One place was painted white with an invocation to liberty, migrando a la libertad,13 each slat wearing a doubled letter, so that it looked like this:

ll ii bb ee rr tt aa dd

three white pairs of stylized handprints marching down the dark metal beneath each letter pair, with crisscross fence wires and white American houses behind and between them. It was as if tiny children had pressed both their palms against that concretion, in tidily understated protest.

I remember a high hill of dirt with concrete houses on it, and right by this an installation of small white crosses. One cross read peace and joy. On another dark slat, three interlaced crosses spelled out la madre and carlos and (this one probably courtesy of some Anglo activist) our love radiates. Other crosses skittered across the wall at odd angles and spacings, then skittered out, overwhelmed at last by the wall’s obduracy.

In a different spot (which must have been closer to the American side’s central district, for beyond the boundary the houses stood grander), a row of weathered wooden crosses leaned against those dark posts, and upon the wall’s slanting, coarse-grained, concrete base someone had written ¡chinga la migra!

Another cross was for jorge solis palma. His presumed death doubtless kept Americans safer. The same could be said of juan mendez, age 18.

Now we had returned to the taxi stand. Once more I tried asking the driver to roll east, and again he refused, since that would entail taking a hill through a neighborhood that was “off limits.” And again I wondered how Antonia and Samuel could have gotten across without a coyote. They might have walked some dreary distance as a matter of course, or perhaps they had paid their respective passages after all, under conditions of mafia intimidation that led them to keep that secret.

Very late that night, a man I met on the street downtown three blocks from the wall (he was a kindly person who offered me crystal meth for free) assured me that the mafias were not gangsters in any bad sense but a sort of local police who protected everyone by “cutting off the hands” of evildoers. He said that poor people who needed to cross the border could count on receiving help from them. Hearing this, I wondered whether Antonia and Samuel had been allowed to pay on a sliding scale.

That was on Saturday. Sunday morning found us back on the Arizona side of Nogales, watching a long freight train clank through a gap in the razor wire and into Mexico, while someone in a black CBP raincoat turned away from it, trudging into the drizzle. Then another man in a black uniform with some kind of official patch on his shoulder inspected the exit place with a weary officiousness. The fixer and I had driven to the Morley Port of Entry because the fixer craved his American chain coffee, and while the Mexican-American barista made it, I asked where the nearest dangerous patch of border might be, because we wanted to see some mafias. Chuckling at my whimsicality or stupidity, she said, “Morley,” so here we were. I must now sorrowfully report that we never got decapitated or even shot, although we certainly garnered eyefuls of the president’s razory tinsel.

We began our safari at the pay phone sign for 4 minutos 50¢ a todo mexico, right there at the crossroads of North Morley Avenue and East International Street with fence and wire commencing at warning—no trespassing—restricted area—keep out—authorized personnel only—u.s. customs and border protection—danger, and there rose the wall with coils of razor wire on top, and before it a low fence to no-man’s-land. The wall itself bore six rolls of razor wire, one on top of the other, with Mexican Nogales (a hill studded with white little houses) on the right-hand side of it, American Nogales already ending on the left, that razory wall marching up the steep hill and over the horizon, shaggily silver-white against that dark wall, a hideous horror that continued east. Silhouetted razor circles dominated the drizzly sky. After a few bends and dips, it lapsed into something more picayune: merely those high dark vertical slats topped with metal plates and spiced rather than saturated with razory wriggles. The Mexican colonias kept on, but our side, the American side, had become beautifully wild desert.

Every time we saw a Border Patrol vehicle, the brash fixer would run over to talk to its occupant. “That guy, he knows everything!” the fixer enthused. “He is sitting here watching for people to cross. As soon as he looks away, a spotter will send them across. Right now, they just take that wire, they cut it, and come on through. He said we can take a dirt road for eight miles and the Army’s still putting up razor wire; it’s all for show. On the other side, it’s not too dangerous, but people do come through. He just said it’s ridiculous, just a game. This is Morley Gate.”

Our newly adorned Great Wall of China kept snaking up and down the red dirt hills, with white Border Patrol trucks at intervals; the eye followed the dark, rusted wall with its silvery razor-wire loops (two rows almost touching just below the top dark rectangles, and a third not far above the halfway mark). Before we knew it, we were at location E8 (the letter designations are used as landmarks, CBP explained), the great silvery Nightbuster lamps shut off just now, of course, the drizzle increasing, the low sprawl of Nogales, Mexico, whitish and grayish and red-roofed behind the slats, while behind me ran that lovely rolling desert. It was almost pretty how the wall frozenly swayed with the land, the lovely sinuousness of it and the narrow vertical rectangles of dark gray sky between the slats achieving if not hospitality at least a sort of geometric excellence.

The fixer leaped out to make friends with the next border patrolman, whom I’ll falsely call Sid: “One thing he said was once they catch them they have two options: give up, or cross illegally again and take your chances. If they’ve only crossed once or twice, they send ’em back, and they probably come back the next day. If you’re legal, once you get your court asylum date, they drop you off at the bus station.” (I remembered what Scott at Diane’s shelter had said: “Back around the first of this year, we had capacity in our shelters, but ICE wasn’t bringing them; they were dropping them again at the bus station. . . . ”) The fixer went on about Sid: “What he said was that ninety-five percent of the people can’t make their court date.”

Guests of Father Sean Carroll, Mexican side of Mariposa P.O.E.

Then up another road we rolled to E14, where a brown-green creek flowed out by some gates and the wall snaked up over itself. At another stop, someone’s empty water bottle stood tucked into a belly-high niche between two great slats of border security, and now lovely desert trees and scrubs ruled the Mexican side, with no more Nogales anywhere. Here was another immense gate, and we arrived at E16, then entered heavier rain, with a small herd of brown and palomino horses behind us. Another border patrolman, a fat sullen one who looked Mexican-American, spied down upon us. The fixer asked him if the razor wire deterred anybody, and he couldn’t rightly say. He told us we weren’t allowed to be here, because this was private land. The fixer said that the very first border patrolman, even before Sid, had told us to roll on ahead, and that shut him up.

E20 was another small gate, then we were looking down a steep gulley into E21. At E25 we chatted with a border patrolman through our respective windows, and the fixer asked: “Does the razor wire slow them down?”

“That’s exactly what it does; it slows them down.”

“Does it stop them?”

“Nothing’s gonna stop them,” replied the young officer, who had just received his degree in unmanned aeronautic systems, which I cleverly guessed to mean drones. Would it have been neighborly and kind to assure him that on the other side of the border, people were more impressed by his razor wire? Old Jorge, for instance, who hit me up for help because he was hungry, and after I bought him tacos hit me up again, estimated that he had been here by the wall for twenty-odd years. “Sometimes you don’t see that many tourists around the first block of the city,” he told me. “Four days are good and three are bad. You don’t see pollos around here that much, because there is a lot of police around this area. Outside the city, that’s where they have that kind of movement.”

“What’s your opinion of the wall here?”

“Many years ago, it used to be all kinds of people getting across the border. Now with this wall, you barely see them. To me, it’s better,” he said, maybe guessing that this was what I wished to hear. “There are many accidents, many things happen. Long time ago, when people got across, you see many people injured.”

“What do you think when the people from Honduras and El Salvador come here?”

“We just gotta give ’em a hand because they need it. They come from far away.”

Three steps on, a man named Simon stood with his hands folded across his crotch, trying to lure me into his pharmacy. He looked great in his dark glasses.

“It’s very tranquil,” he said, “but sometimes I see a bit of fear. They just put up the razor wire, so now it’s more risky. Now I’m thinking it’s gonna be more difficult to cross over from there. A normal day is like today. . . . ”

“What do you think about the people from Central America coming here to cross?”

“They’re coming for food, and a lot of them are cold, but they are causing problems sometimes for the people who live here. They’re gonna stay for the housing and the jobs,” he thought. Then he said: “They’re looking for a better life, and we have to support that.”

Mexican side of the border wall, east of Mariposa P.O.E.

In short, even though Simon and Jorge might disagree with the Border Patrol, not to mention the Trumpeters, as to whether the migrants should be “supported,” at least they believed that the razor wire was effective. It is always lovely when the minds of two nations can meet on something. Thus uplifted, the fixer and I said goodbye to the young officer who had studied drones. From here one could see Mount Washington, which marked the next sector. The border patrolman said that it was merely two more dips down to the Santa Cruz River, where the wall gave way to Normandy fence, as one called arrangements of those caltrop-like entities, similar in shape if much inferior in size to the Nazi defenses off the coast of Normandy, which showed up here and there on the Mexican side to discourage vehicles. I sat looking through the white-speckled windshield at the river streaming through the comb tines across the frontage road and then down past canted strata in sedimentary rock of a dark red-brown color. The creek wound down through gravel and grass toward a white bird that I thought too small to be an egret; maybe a heron. On the way back we saw real cowboys.

On Monday afternoon I thought to try the eastern way again from the Mexican side. The fixer and I, in company with our just-arrived interpreter, were returning from some interviews at Father Sean’s migrant center, which, as it turned out, lay only one long block south of the Mariposa Point of Entry. I had asked this fine priest, whom even the atheistic interpreter was willing to consider nearly saintly, whether he had experienced mafia difficulties, and he replied much as had the face-covering policeman: “I mean, there’s a cartel here, but I’ve never had that. . . . During the day it shouldn’t be a problem.” But the taxi driver who brought us back allowed that “from here to the railroad tracks” there were several gangs, and on the other side of the tracks only one. He knew those characters pretty well. They were his passengers; they pulled their shirts up and showed him that they were wearing pistols. Thus informed, we all had lunch, and then it came time to snag another taxi driver, who agreed so long as his conditions would be respected. Usually my fixer sat in the front because he liked to make movies. This time I sat up there with my laptop open as usual, while the fixer and interpreter sat discreetly in the back.

Following the sign for usa retorno, we then made a U-turn at the train tracks, which is to say (according to the previous cab driver) the mafia border. Passing a long string of graffitied grainers, a boxcar, and some stack cars, we ascended an overpass toward the U.S.A., then zoomed down, accompanied by a bright yellow railing, toward Garita Peatonal No. 2. As we began to climb a winding street, the driver’s conditions came into force. The laptop was unproblematic, but neither my camera nor the fixer’s cinematic apparatus was allowed. As at Mariposa, I could see no hint of danger anywhere. Truth to tell, I would not have taken the driver’s say-so had not so many other drivers previously darkened the picture. I saw small concrete houses and walls of stone and brick, a barbershop, and we continued up the narrow street. There was hardly any traffic. We turned left onto Lagunas de Tamiahua, then suddenly came the wall. From here on out the driver permitted me to take two or three widely spaced photographs, but only from inside the taxi, and, needless to say, he made me promise to include him out. We ground up a steep gravel road, not without strain on his car, heading toward the summit, with that reddish border wall at some distance on the left; then came sky.

“If they come it’s very dangerous,” he said.

And maybe one of them did come, although I failed to see him, being busy with changing a roll of film. The driver grew quiet and ducked his head. The fixer said that there was a man in a truck with a German shepherd, and that this man looked at him. Like most fixers, he was cheerfully, aggressively rash (he had filmed terrible things in El Salvador and went right on fixing); in our trips together my cautiousness sometimes disappointed him, and so the only evidence I have that this man might have been mafia was that the fixer, who looked back at him, sounded convinced, maybe even cowed, and described him as a thug. I asked for a description, and he said the man was wearing a dark blue shirt. Was I supposed to piss my pants over that?

The driver very evenly remarked, “Well, sometimes they take your license plate number, and then they come find you, but this time they didn’t seem to take anything down.”

On the summit came a brief stretch of pavement; then the road returned to rocks and dirt, with the wall on our left and nothing but nature on the American side. This place was called Colonia Buenos Aires. Now the driver enacted another condition: we began winding left and right on paved streets, since the dirt road by the wall had now become too “dangerous”; for all I know, he meant only that it was too much for the vehicle’s suspension. We climbed a hill toward the Parque Industrial.

“Do any of these mafias have a name?”

“I wouldn’t know what to say.”

We were now some distance from the border, with dry hills hummocking the wall out of sight. When we reached a huge spiderlike agave I could see it again, so I asked whether it would be safe to stop and take a photo.

“No,” he said, “because they have checkpoints along here and you don’t want them to stop you.”

“What do the checkpoints look like?”

“Several cars blocking the road, and armed guys.” He added: “You don’t always see them. They’re sometimes hidden behind the bushes.”

Another truck went by, with dogs in the back and tough-looking men in front. The driver called them mafias, but how would he or I ever know for sure?

There was the tiny red ribbon of wall and a Border Patrol vehicle beyond it. Very likely its occupant was someone whom the fixer and I had met on the previous day. “That’s where the people go,” the taxi driver said, referring to the migrants. But there was still wall, so Antonia and her child must have gone farther, one way or the other.

The road improved and the yellow grass got greener when we began to swing south into the Lomas de Anza, or De Anza Hills.

Approach to DeConcini P.O.E., Nogales, Mexico

“Who lives here?” I asked.

“People who work in the factories.”

“Are they afraid here?”

“Well, they’re afraid, but they just have to tough it out. What else can you do?”

“Is it just as dangerous here, or safer as we go away from the wall?”

“Yeah. Safer.”

So we swung west again toward usa and nogales centro, riding the highway called Plutarco Elías Calles, and I never saw anything provable. When I had paid him, I asked the driver why he had taken us if it was so dangerous, and he replied, “Well, someone had to take you.”

So, reader, what should you or I conclude about these mafias? Fortunately, I can now proffer an utterly, awesomely apodictic source: the Trumpeter Swans.

v: the rally

Thursday’s Arizona Daily Star had announced that “some of the most dedicated allies to President Trump’s vision to build a new border wall are holding a town hall in Green Valley on Friday.” These allies included the famous blowhard Steve Bannon, former Colorado congressman Tom Tancredo,14 and Brian Kolfage, a triple-amputee veteran who began a $1 billion GoFundMe campaign to privately finance a proposed border wall. Appropriately named We Build the Wall, the group hosted its event at the Quail Creek Country Club. Initially, it was free and open to the public, but by Thursday it was open only to members of the Quail Creek Republican Club. On Friday one of Diane’s volunteers told me: “Earlier in the week they said everyone was welcome, and now they say that only Republicans are welcome. In the paper they said they are only going to allow Quail Creek Republicans in there.” Green Valley being perfectly located on Interstate 19 between Tucson and Nogales, I decided to be a Trumpeter along with the rest of them, especially since I wore a red, white, and blue baseball cap that read butchers of america. (A week later, since it had served its purpose, I gave it away to a nice girl in Raleigh, North Carolina.)

It was a wide room, filled almost entirely with white people like me, most of whom were old, but right in front of me sat a young man whose hair went down to his shoulders. He wore a black T-shirt whose back read patriot movement az; on the front, in homage to the old Pink Floyd album that had called upon us to tear down the wall, was a brickwork vista inscribed build the wall. His friend beside him wore the same getup.

Brandon Darby, Brian Kolfage, and Neil McCabe at an event billed as a town hall on border control,

Quail Creek Country Club, Green Valley, Arizona.

The great Mr. Bannon would not take the limelight for a good half hour yet; when he did, he spat out such oratorical pearls as the following:

moderator (a certain Neil McCabe): Steve, how did you get involved in this?

steve bannon: Someone gave me a call right after, well, I’ve known Brian for years. . . . And he just said, you know, he might want to think about flipping this from funding a wall where the money just goes to the U.S. Treasury . . . to a citizens’ action initiative to actually build a wall! . . . And Brian talked to the GoFundMe people, and here we are today! . . . We put the original gangsters or the O.G.s of the MAGA movement together to help.

“And if anyone who’s not media wants to ask a question . . . ,” said an event worker. Since I had situated myself beside a friendly old man who said, “Please,” inviting me into an empty seat, I upraised my un-American ears just in time to catch Brian Kolfage trumpeting:

We definitely need that. We need to know that intel of where people are coming across. We don’t wanna slap up wall where it’s not having an impact. We want our sections of wall to have . . . the biggest impact right away.

Three glare-washed men sat on the stage before a kind of triptych that spelled out: we build the wall we the people will build the wall. This latter profundity occupied me for nearly a second.

“Do you want another question?” asked an event worker.

“I’m a resident here. What type of feedback, if any, have you gotten from the Trump Administration?”

The triple-amputee veteran replied:

Feedback has been positive. . . . The president supports what we’re doin’. He approves what we’re doin’. And when we start breaking ground, we’re gonna be basically supplementing what President Trump is doin’, if he ever gets the funding!

And the audience chuckled sympathetically.

I think they’re projecting two hundred and fifty miles of border wall in strategic locations. We are gonna match whatever the president does. If they do two-fifty, we’re gonna shoot for two-fifty, because we all know that that two-fifty that he’s doing is not enough to impact everything that we need. We have two thousand miles of open border, and the cartels are very adaptive, and we need to secure our entire border.

“Brandon,” McCabe was saying, “I don’t think there’s anyone who knows the border like you do.”

His answer:

We’ve been trying to expose cartels and tell the stories of Border Patrol agents and communities along the border, on both sides of the border. It’s not just the U.S. side where people are getting hurt by cartels, right? And we’ve been tryin’ to tell the story for almost a decade now, traveling all nine sectors, going into Mexico, and we’ve developed sources that are just unbelievable sourcing in Mexico, so we have sources on both sides. And to see so many people fired up and supporting Brian’s effort, and to see my old boss Steve Bannon join the effort, and to see so many people like you come, it, it, really, honestly, I could get choked up, because I see that we are, we are gonna win this. We’re gonna win this. We’re gonna fight for this!

And everyone around me cheered. When I forgot to clap, a lady stared at me.

So here’s the bottom line. I was very hesitant to get involved. We have been trying to stick it to cartels, to Mexican cartels, and make people pay attention in this country, to what specific Mexican cartels are doing to our country. And it feels like we’re yelling at, at a roof, like our ceiling, like no one’s hearing us, or very few people hear us. And when I started to realize that this group was going deeper, it’s like, like, hey, we need to build the wall. That’s one part of a multitiered solution to a very complex problem. But we also need to stick it to cartels, right, like we have to secure our country. When I realized this group was all about it, I joined in, and I’m honored to sit on the stage with you, and I really appreciate what you’ve done.

Audience at Quail Creek Country Club

Uplifting their heads, my fellow citizens applauded, cheered, and murmured to one another. A woman’s spectacularly eye-shadowed peepers were shining with excitement. The lady who had caught me not applauding now repeatedly turned to glare at my laptop’s clickety-clack. (Had I been outed as a media agent?) A white-haired old man shared yet another secret with a middle-aged blonde’s ear, which neither twitched nor wiggled. A man in a pinstriped shirt was beaming, and a man in a soft sweater leaned thirstily forward. Ladies and gentlemen, I dub this democracy!

mccabe: Is a wall possible and useful at certain sectors of the border?

brandon darby: The bottom line is this. If you build a wall across the entire border, all the way to the moon, then the cartels are going to switch to come in through ports of entry. And if you secure ports of entry, then they’re gonna find a way to go back and get between ports of entry. The facts show that fencing, barriers, walls, depending on what’s needed in a specific area, absolutely work. Do they work one hundred percent? Do they end all of the cartels and make Mexico okay again and America okay again? No. Are they a vital component of that? One hundred percent. And I don’t think a serious person could allege otherwise. . . . Fencing and walls are a part of a larger solution—a big part.

He was correct. Let’s hear it from the horse’s mouth! Asked about the razor wire, the Mexican policeman who had covered his face assured me: “It does make a difference. This side, they don’t have to worry much about people crossing over. In November I did see a guy trying to cross and he got stuck up there; the wire did its job. He ended up getting helped down. . . . ”

So much for the deterrent. Now what about the threat? I mean, what about these mafias? Bannon’s boys laid it out:

darby: If you look at the DEA map of the cartels . . . they’re gonna say the Gulf Cartel controls from the Gulf of Mexico to Zapata, Texas . . . Del Rio sector and then it’s Sinaloa . . . and then the Juárez Cartel . . . and all the way to Tijuana, Mexico. But that’s just not true. Well, it is true, but it’s not true. The Sinaloa Cartel is made up of hundreds of different organizations. And those hundreds of organizations operate under the banner of the Sinaloa Federation. But they’re all different cartels, and they all have different temperaments. Some grow marijuana. Some grow poppy. Some manufacture fentanyl and methamphetamine. Some simply traffic drugs. Well, changes that we made in this country ultimately led to some of those groups saying, hey, we can’t make money off of our horrible marijuana anymore. So we need to switch to something else to replace our profits. And when you look at the Gulf Cartel, the Reynosa faction, they switched to human smuggling, and so now they make as much or more from smuggling people into our country! . . . Most of the guys you’re dealing with in Arizona still focus on drugs, but now they’re starting to say, wait a minute, we can focus on human smuggling, too, and we’re going to make all of the money from that as well. So this has become, illegal immigration has become, a fuel for the cartels in Mexico. So the liberals who think that they’re helping people in Mexico or Central America by allowing this to continue are actually fueling the very groups people are trying to get away from in the first place.

mccabe: What is it a head?

(I myself am seeking to turn myself into a human calculator and am dusting off three integrals and contemplating the square root of two when . . . )

mccabe: What do they make a head?

darby: It depends on the group. If we’re talking about the Reynosa faction of the Gulf Cartel, which is the most prolific, then I’ll tell you this. They generally charge somewhere between five and ten thousand a head. . . . And they’ll say: Here’s the deal. If you wanna go there and you wanna request asylum, we’ll let you do it for five grand. But if you wanna go there and you want us to sneak you in and really get you to Houston or Dallas or Tucson or Phoenix, then we’re gonna, it’s going to cost you even more, maybe twelve to fifteen thousand. So these groups are really making money. . . . And it’s a fact that last year, there was eleven to twelve hundred people per day apprehended. And remember, we only apprehend half of ’em, right? Approximately. Eleven to twelve hundred people per day apprehended, crossing our southern border. Per day.15 Now you think about the amount of money that is to those criminal groups—not only the amount of money that it’s going to cost you in the long term to educate those people and provide health care. . . !

The Trumpeters weren’t making it all up. The Mexican policeman who had covered his face, and now sat so agreeably beside me on the bench as we watched the asylum seekers and lucky card-holding border crossers go by, definitely believed in the mafias. When I asked how many migrants he saw at this port of entry, he answered: “I could say right now there’s more people. For the situation in Mexico, the violence, a lot of it in Guerrero . . . ” His voice trailed off.

“How many migrants cross per day in this sector?”16

“Maybe a hundred illegally.”

“And how many legal asylum seekers?”

“In our shift, maybe twenty-six daily.”

He estimated the current list of asylum seekers in Nogales at maybe within one thousand. A young man whom I had interviewed here the previous day (he is one of two Nicaraguan Josés in this essay; the other you will meet at the Eloy Detention Center) was number 988. His initial entrance interview would come up in another three or four days. A migrant coordinator named Brenda, who worked in Nogales, explained to me that if he were rejected out of hand the Americans would send him back across the line; otherwise he would win the great fortune of getting his merits further considered, in which case, being a single male, he would sit (estimated Brenda) in detention for something like six months17—a fabulous method for converting him into an America lover.

The Mexican policeman must have been correct about Guerrero. At the next border crossing, which lay a ten-minute taxi ride westward, Victoria, dark, beautiful, and number 1,036 on the asylum waiting list, stood in the chilly sidewalk queue for Father Sean’s soup kitchen. She hailed from Guerrero: “There’s lots of violence; I fled from fear. My daughter wants to study. . . . ”

Guests of Father Sean, Mexican side of Mariposa P.O.E.

“Where does the violence come from?”

“The mafia controls that sector, and they are killing people.”

They had threatened her neighbor “directly,” and her ten-year-old daughter could not even safely walk to school. “The mayor doesn’t stand up for the community.”

“Why do they do this?”

“Nobody knows why.”

Their journey thus far had taken two nights and days. Victoria had wrangled rides in cars and trucks.

“What do you hope and expect?”

“My compañera, the godmother of my daughter, lives across the border. I hope to get my daughter into school and treated for asthma.” So the Trumpeters were exactly right in their fulminations regarding “the amount of money that it’s going to cost you in the long term to educate those people and provide health care. . . !” Wicked Victoria!

Behind Victoria stood Mariella, whose migration thus far had taken four days of “hitchhiking in cars.” Her group consisted of two families. “Everybody was kind, thanks to God. We want to request asylum. My brother’s in Arizona.”

“What made you decide to leave Guerrero?”

“The violence,” she said patiently.

“Were you threatened directly?”

“Lots of people appear dead in the streets. Sometimes they’re shot and sometimes they’re hacked into pieces.”

“But why?”

“Nobody knows. It’s better not to ask.”

The policeman said that increasing numbers of the migrants were children. “It’s more about mafias; they’re trying to recruit people that look younger, and that’s because they last a lot longer. In my shift today, we received, I think, five or six from the first caravan. I received a kid underage who said he was in a caravan. So we passed him through.”

Well, didn’t that likewise prove the Trumpeters’ point? Darby enlightened us as follows: the cartels (who may or may not have been the mafias) might overwhelm a certain border sector with children, and while the poor Border Patrol agents were coping with those, in zipped a monster load of drugs! Oh, oh, oh, how diabolical those cartels were! And that Mexican policeman, hardened in sin, kept facilitating their evil projects: “I’ve gone to the spot where there’s some woman about nineteen who had nothing, who came with her kids, and she had no money. So I gave her ten dollars plus a hundred pesos that I had in my pocket; she had a one-year-old baby.”

vi: “so happy to be in safety”

Eloy Detention Center, Arizona

To address the Trumpeters’ arguments I would now like to invite you through the three gates of ICE’s Eloy Detention Center, then past the security man and to his metal detector. My butchers of america cap needed to be locked up because red, white, and blue might, as the security man explained, incorporate gang colors. Having passed my scan, I stood behind his workstation waiting for the interpreter, who had to run back out to the parking lot to verify the rental car’s license plate number, so that I had full opportunity to admire the two charity-purposed vending machines; one sold phone credits, and when I asked the first interviewee, Eulalia, which gift would best delight her, she chose that one, both of us being ignorant that international calls were prohibited. (A Harper’s Magazine fact-checker found out that they weren’t.) Since all these detainees were from elsewhere, the phone credit would avail her about as much as the security man’s hypothetical good wishes. (He was actually a convivial sort, who cracked jokes with incoming guards; and while I awaited the interpreter’s return, we even carried on a conversation about the weather, the faraway end of his shift, and the famous Indian ruins of Casa Grande; they were a quarter hour’s drive away, and he had never been there.) The other vending machine sold commissary credits; at least that was what I thought he said. But at the end of the two interviews, when they let us out of there, the interpreter successfully masking her angry grief, I was told that the only method of contributing to a detainee’s account was via that reliable old gouging service Western Union, so that was what Eulalia would get. Western Union took a smaller bite if one sent the money electronically than if one walked into their office, so I gave the interpreter a hundred-dollar bill and she contributed a hundred of her own, then did something on the computer; Eulalia therefore would theoretically eventually win ninety dollars, although I wonder what she made of my apparent breach of promise to give her the wherewithal to telephone her home country. Well, why dwell on bad things, especially when they happened to other people? I myself had much to praise Providence about. For one thing, nobody searched my anus that day. (The U.S. government has done that only once in my life, back in my hitchhiking days, so I should have gotten over it, but for some reason I hold a grudge.) Better yet, not only did they let us in, they did (I reiterate) let us out! And so we were smoothly promoted from the security man’s domain into the shiny-clean white room behind and to the right of it, complete with two mirror panes, a soda machine, a snack machine, and a regiment of molded foam chairs—seamless and crackless, you see, so that nobody could hide contraband in them. I also noted a line of restrooms and a small TV that was broadcasting an unwatched thriller.

A guard now asked which detainee I would like to see first. “The lady,” I said, for I have always been a ladies’ man.

So there we now were, in one of I don’t know how many windowless side rooms, ensconced in two of the chairs in that row on one side of the wooden partition. Right away they brought in Eulalia, who sat down in one of the chairs on the other side. There was no transparent wall between us, Eloy’s security flavor being officially “minimum.” Nor did any guard stand listening. For all I knew, the room wasn’t even bugged.

The interview arrangement procedure had been as follows: One could hardly just wander in, as I used to do in Mexico, and ask a guard whether any captives felt like talking. Oh, no! That would never be consonant with border security! Therefore, to keep you and me safe, one had first to inquire of an immigration lawyer whether any detained clients felt willing; if yes, one had to order up these persons by name and alien number. The third step was to be approved by ICE. Next, ICE required verification of the media outlet under whose auspices I was going to have this pleasure. (My editor at Harper’s vouched for us expeditiously.) The final step was to find the place: 1705 East Hanna Road in Eloy. So we drove to that town, but at the convenience store they didn’t know anything about it and seemed almost uncomfortable that I had asked in front of the customers; or maybe its existence depressed them since they were all Latinos. Finally, a lady in the back directed us to return south to the previous town, then drive east, at which point the detention center lay alone off a long, flat sandy stretch, being a long, pale rectangular block of slit-windowed nastiness behind a fence less impressive than the border wall but hardly welcoming.

Now back to Eulalia: she was tiny, with bright black eyes and a long braid, and projected a flat affect in keeping with that ugly room in that hateful place. The interpreter, who was a linguist by profession, with special qualifications both academic and practical in Mesoamerican tongues, informed me that her Spanish was mostly excellent, although she could not conjugate certain verbs, her native language being a Mayan one called Kanjobal. She had been educated up to the third grade. Her home was the little pueblo of Santa Eulalia, near the large city of Huehuetenango.18 They had dressed her in orange.19