Upon the election of Andrew Jackson, the conflict over the rights of the states had reached a perilous height. The Constitution was on a lee shore; neither the sun nor the stars could be seen for many days, and the roar of the breakers sounded in the ears of all men. South Carolina was about to test the strength of the government.

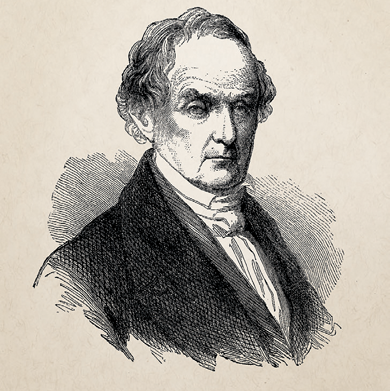

A portrait of Daniel Webster, which appeared in the December 1852 issue of Harper’s Magazine

When Daniel Webster, senator from Massachusetts, appeared in the Senate chamber that morning, January 26, 1830, he saw the full magnitude of the occasion. Mr. Webster advanced in his great argument with a bearing nothing less than majestic. The tournament, upon which the eyes of the whole country were fixed, was to him not a field for display, but a real field of battle. He proceeded, before entering upon the constitutional argument, to state the opinions of the party of which Senator Robert Y. Hayne from South Carolina was the chosen representative:

That it is the right of the state legislatures to interfere whenever, in their judgment, this government transcends its constitutional limits, and to arrest the operation of its laws.

That this right exists under the Constitution, not as a right to overthrow it on the ground of extreme necessity.

That if the exigency of the case require it, a state government may, by its own sovereign authority, annul an act of the general government which it deems palpably unconstitutional.

Mr. Webster then stated his own view. He did not deny the inherent right in the people to reform their government, nor to resist unconstitutional laws. “The great question is, Whose prerogative is it to decide on the constitutionality or unconstitutionality of the laws? The proposition that, in case of a supposed violation of the Constitution, the states have a constitutional right to annul the law, is the proposition of the gentleman. I do not admit it. If the gentleman had intended no more than to assert the right of revolution for justifiable cause, he would have said only what all agree to. But I cannot conceive that there can be a middle course between submission to the laws, when regularly pronounced constitutional, on the one hand, and open resistance on the other.”

He then uttered that splendid peroration which will thrill the hearts of the American people until the republic falls into utter and irretrievable ruin:

“I have not allowed myself, sir, to look beyond the Union, to see what might lie hidden in the dark recess behind. I have not coolly weighed the chances of preserving liberty when the bonds that unite us together shall be broken asunder. I have not accustomed myself to hang over the precipice of disunion, to see whether, with my short sight, I can fathom the depth of the abyss below; nor could I regard him as a safe counselor in the affairs of this government whose thoughts should be mainly bent on considering not how the Union should be best preserved, but how tolerable might be the condition of the people when it should be broken up and destroyed. While the Union lasts, we have high, exciting, gratifying prospects spread out before us—for us and our children. Beyond that I seek not to penetrate the veil. God grant that in my day, at least, that curtain may not rise! God grant that on my vision never may be opened what lies beyond! When my eyes shall be turned to behold for the last time the sun in heaven, may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union; on states dissevered, discordant, belligerent; on a land rent with civil feuds, or drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood! Let their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous ensign of the republic, now known and honored throughout the earth, still full high advanced, its arms and trophies streaming in their original luster, not a stripe erased or polluted, not a single star obscured, bearing for its motto no such miserable interrogatory as ‘What is all this worth?’ nor those other words of delusion and folly, ‘Liberty first, and Union afterward,’ but everywhere, spread all over in characters of living light, blazing on all its ample folds as they float over the sea and over the land, and in every wind under the whole heavens, that other sentiment, dear to every true American heart—Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.”

From “Webster and the Constitution,” which appeared in the March 1877 issue of Harper’s Magazine.