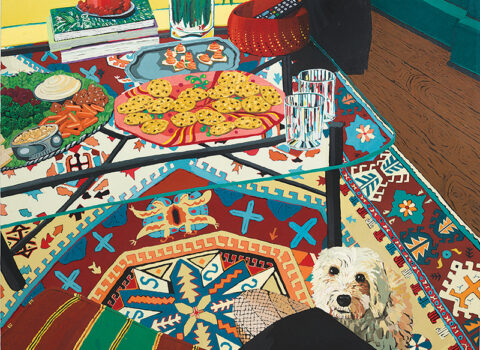

Paintings by Henni Alftan © The artist. Tiptoeing 1/2 (left) and The Thinker 1/2 (center left). Courtesy Karma, New York City. Landscape (center top), Pleats (center bottom), and Don’t Look Back (right). Courtesy Galerie Claire Gastaud, Clermont-Ferrand, France

how high? that high

He had his stick that was used mostly to point at your head if your head wasn’t held up proudly.

I still like that man—Holger! He had been an orphan!

He came up to me once because there was something about how I was moving my feet that wasn’t…