Paintings by Yann Kebbi for Harper’s Magazine

i did trip over a very small boy

I did trip over a small boy who fell down and cried, and I feared very much that I had kicked him.

He must have been wondering about the monster—me—even after his rescue.

But whose glass was I holding? And which bitter drink had I just tasted when Mother said, “Damn it all!”—and laughed? My mother rarely laughs in my presence.

“I want my wife!” I shouted. I surprised myself. “We’re leaving!”

She was back behind the Wassermans and the Cordells, and that little boy I’d knocked down was with them, too, speaking softly. His mother had to bend quite low to listen—his legs, I figured, were no more than a foot long.

First, we had to dodge so many people. I was, however, bound by the low ceiling in Mother’s house, and I feel like a giant in her house.

I heard my wife, Jacquenette, say to Dale Cordell, “All right, then,” and this was jarring, because she often says that just before bed, where I can grab her, for starters, and then clamp down. But I don’t really mean clamp down—I mean something much nicer.

In bed, my feet found hers, and she said my hand was too heavy and that it hurt her hand to hold mine, so she petted my arm, and I thought that that might serve me.

But I want to try again soon to get a better result, when I’ll go rung by rung to different stages.

Too early the next evening, Jacquenette looked to be asleep in bed.

“Did I disturb you?” I said, and I advanced with care.

The buffeting noise—perhaps it was a flight of birds I heard through the open window—distracted me.

And yet I did set everything into motion by doing some light tapping on her body that did not cost me anything—my brushless style.

My thoughts were: What do you feel if I do this? If I do this? If I do this?

Still, what about my wife’s face? Its shining surface would repay me for my efforts.

You know, I’d much rather note scenes of everyday life around the house—speaking to neighbors, dusting.

Odd thing—our oatmeal took twice as long as usual to cook this morning.

I don’t think it liked the pot.

i liked rex

I had just met Devin Stamp!—and I would have liked to hold on longer to our promising, necessary bond, but I was visiting him for only two days—during which time I was often blushing.

It was as if tiny lights were continuously being switched on when I got off the train to go home, because dandelions lined the sidewalks, and these weeds blinked at me.

An envelope was waiting for me at home, addressed in a familiar hand—from Rex!

Oh, I want to have plenty of reasons to believe in activities that are stimulative.

I remembered when his big head was above mine, my ear on his warm chest.

Rex Pickens wrote: I have heard that you are lonely. I need to tell you something that cannot be said in a letter.

When we met up, Rex looked to me brightly painted. He wore a heavy wool suit I’d never seen before—glen plaid, a houndstooth check—and next, in bed, I thought his very pink privates were meant to be some cheery dessert.

So how come I am never with him anymore?—because he never said he had the time.

But Devin does have the time, and he and I, only yesterday, were basking and stripped bare.

As I write this, my face is turned toward you, the reader, and due to ill health, I have thin, downturned lips, which often work to extol and to uplift—why not Devin?—because that’s lulling.

And here I am now, stroking my pet—my sheltie—although it is impossible for me to remain in this position for long—not quite sitting, standing, or lying down—because we are both leaning up against ground that steeply slopes.

Below I can see how my town is enclosed within a very narrow area, between these hills and the sea.

True, we are prone to sea storms and landslides, but this village also provides a panoramic view, amusements, and benefits, as well as a horrid gorge. But don’t let’s look at that. Let’s be happy.

Let us enjoy our holidays and let us fall for or swear by whatever we want to—because people really like to!

for pity’s sake

The Krautheimers—rather, dub them the Goodenoughs!—rose to power near what, in this era, we are calling their violent emotions.

Though nowadays the Goodenoughs rarely have their gall, jealousy, or alarm.

On holiday, the old woman enjoys a tropical garden—any member of the public can visit—that is filled with pearly shell-ginger blossoms and lots of blue daze.

This is dreamland to her—although she does have that pesky parapsoriasis on her torso.

Certainly her overeating is risky after middle life, and her body’s tolerance for sugar has waned.

Often among such old women, of course, a search for beauty is not uncommon.

“Oh, look at the pretty black-and-white-spotted bird,” the old woman says. “Oh, the bird is afraid. The birdie is afraid. That poor bird. That’s a pretty one!”

“What I want to know,” her old husband says, “is why does this palm tree have a smooth sock over its trunk—it looks like—when the rest of it is so rough?”

“Watch your step!”

The oldsters hear this said from behind them.

“I say it in my sleep.”

In the evening, the old man says, “Is that new? You look so cozy in your nightgown!”

She has had it for years, and the gold-brown gauzy gown is ugly. Her teeth are nearly golden brown, too—very worn.

Regardless, the old man has a renewed interest in his wife. He deems her sensible and polite—and is delighted she is within easy reach.

Must there really be a need for harsh realism?

The old man just saw his dear friend Chris Hake, who certainly did have Chris’s manner of walking, but, alas, he did not think the man had Chris’s head!

Next, it looked like Giselle, the old man’s long-dead daughter, had come along.

She appeared sullen enough to be dead, he thought, but was far too tall to be his daughter.

A tot stood before him, with its fist pressed into its cheek, eyes closed, enraged or in pain, still and all— not complaining.

That’s okay.

Yes, okay, but this story is just not good enough yet. How about the old woman is an heiress!—seated at a gala feast, at a long, long table. There are thirty guests! Her ring boasts a gem as big as an ice rink, and it is passed around to be admired, so this heiress fears for her ring—well, she has pangs of anxiety, some regrets.

diane!

What in the world will her name be? Diane!

I should not hurt anybody else I know with this story.

I hope she is not too fake.

At the lake she is often cheerful, although her eyebrows are frequently raised—a common response to the untoward or to the unexpected.

A highly dangerous path leads to the lake. But why say that?

It is not really dangerous—still, she should mind the uneven ground, the sudden downhills, and watch out for overgrown brambles, including the dewberries with small spines and stickers.

She found herself on this day staring more deeply into her sorry romantic efforts than she ever did into . . . Why is the lake so hard to describe?—the wide water that is not the sea, but surely looks like it.

Sometime after lunch, her friend Ellen Torch showed up to say, “I saw Fabio at the hardware!”

“Did he see you?”

“He did not. His nose was different, and his face looked boiled—and I thought of you!”

“You thought of me? What shoes was he wearing?”

“Sneakers. His gray hair was hanging down, awfully long.”

“He doesn’t have gray hair.”

“Well, it was hanging down, and I thought of you.”

“I have gray hair.”

And hadn’t Fabio and Diane once been the rulers of this house?

In the upper part of the house is the long hall, like the stem of a weed whose little fruits are the several nice rooms that branch off from it.

There’s the room Diane sleeps in, where she and Fabio had often fought, with its window that frames the magnolia, and when the tree blossoms, Diane tries to remember to stare long at it, to take its character all the way into herself and to keep the tree in there.

“Fabio’s here!” Ellen said. “I see him! Let me hang up your coat.”

So, is he friendly?

For a fact, Diane is too ill-equipped to know.

“So, which do you like?” Fabio said, pointing.

“This is my favorite,” Diane said.

“I chose it,” he said. “I remember saying, when we bought it, I want the one with the little neck.”

“Will you stay here?” Diane said.

No!

And the vase he carried off was never meant to parade with flowers. Its neck is far too skinny and would only asphyxiate any bloom.

Fabio sneezed several times, was blessed, and then he left with treasure.

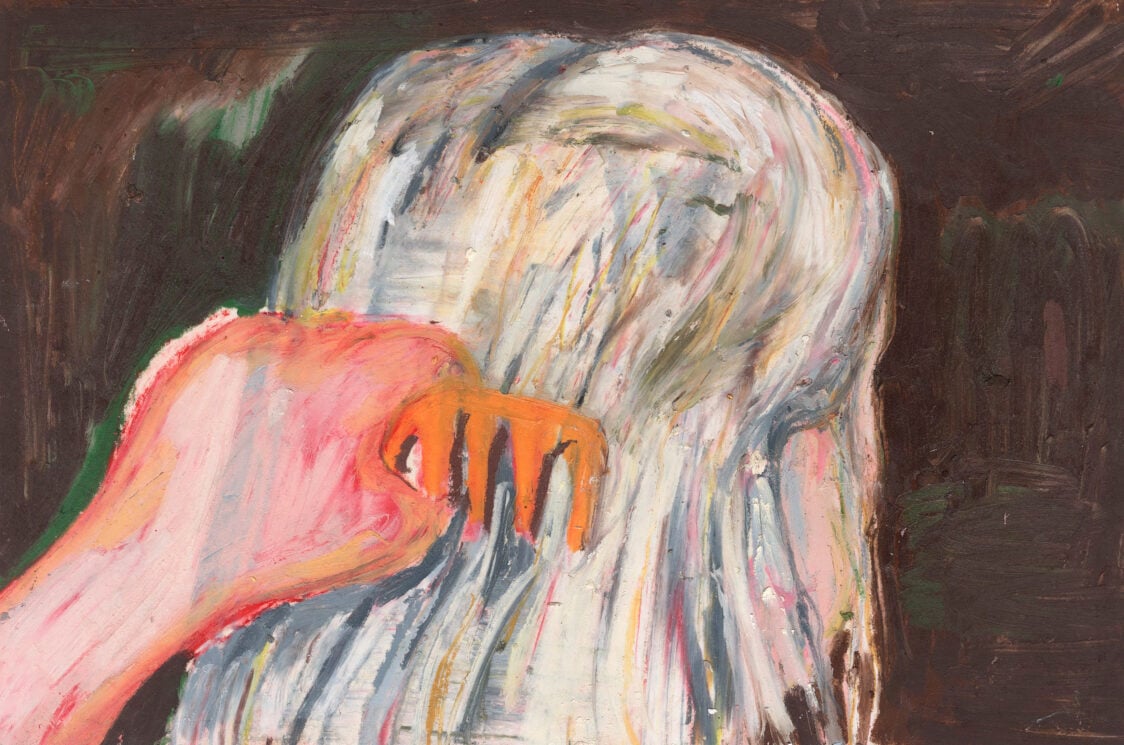

By dinnertime, this story is ending, and we leave Diane behind—combing her hair how she does with her saw-cut comb.

She is kneeling—pleasing me as she combs. She supplicates herself for someone, something!—for me.

And she is authentic enough—a genuine imitation.

I love her finger rings, her strings of beads, the various stones—lapis and carnelian. . . . I like the grosgrain ribbon in her hair that she has had to unloose. All this stuff and stuff, to my mind . . . is what I revere. It is the best of her.