I am eight years old, sitting in my childhood kitchen, ready to watch one of the home videos my father has made. The videotape still exists somewhere, so somewhere she still is, that girl on the screen: hair that tangles, freckles across her nose that in time will spread across one side of her forehead. A body that can throw a baseball the way her father has shown her. A body in which bones and hormones lie in wait, ready to bloom into the wide hips her mother has given her. A body that has scars: the scars over her lungs and heart from the scalpel that saved her when she was a baby, the invisible scars left by a man who touched her when she was young. A body is a record or a body is freedom or a body is a battleground. Already, at eight, she knows it to be all three.

But somebody has slipped. The school is putting on the musical South Pacific, and there are not enough roles for the girls, and she is as tall as or taller than the boys, and so they have done what is unthinkable in this striving 1980s town, in this place where the men do the driving and the women make their mouths into perfect Os to apply lipstick in the rearview. For the musical, they have made her a boy.

No, she thinks. They have allowed her to be a boy.

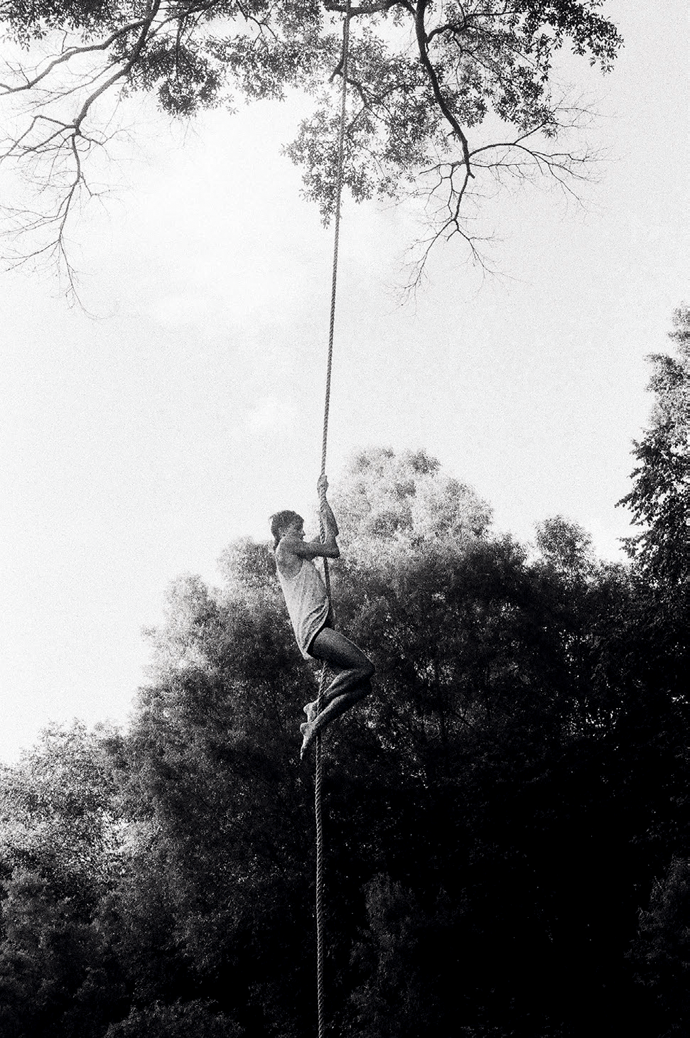

Photograph by Annie Flanagan of Linden Crawford, from their collaboration All in One Piece © The artist

What I remember is the flush I feel as my father loads the tape into the player. Usually I hate watching videos of myself. Usually there is this stranger on the screen, this girl with her pastel clothing, and I am supposed to pretend that she is me. And she is, I know she is, but also she isn’t. In the third grade I’ll be asked to draw a self-portrait in art class, and for years into the future, when I try to understand when this feeling began—this feeling of not having words to explain what my body is, to explain who I am—I’ll remember my shock as I placed my drawing next to my classmates’. They’d drawn stick figures with round heads and blond curls or crew cuts; they’d drawn their families and their dogs and the bright yellow spikes of a sun. One had drawn long hair and the triangle shape of a dress, and another short hair and jeans. How had they so easily known what they looked like?

I had drawn a swirl.

Now, in the kitchen, what I notice is that my siblings are squirming in their seats, asking if they can leave—and that I, somehow, am not. I am sitting perfectly still. Is it possible that I want to see this video? The feeling is peculiar. I have not yet known the pleasure of taking something intimately mine and watching the world respond. Someday, I will be a writer. Someday, I will love this feeling. But at eight years old, my private world both pains and sustains me, and sharing it is new.

My mother hushes my siblings and passes popcorn around the table. My father takes his spot at the head. Onscreen, the auditorium of an elementary school appears. At the corner of the stage, there are painted plywood palm trees.

Then the curtains part, and there I am. My hair slicked back, my ponytail pinned away, a white sailor’s cap perched on my head. Without the hair, my face looks different: angular, fine-boned. I am wearing a plain white T-shirt tucked into blue jeans, all the frill and fluff of my normal clothing stripped away—and with it, somehow, so much else. All my life, I have felt ungainly—wrong-sized and wrong-shaped.

But look. On the screen. There is only ease.

I don’t know whether the hush I remember spread through the kitchen or only through me. My mother is the first to speak. “You make a good-looking boy!” she says.

I feel the words I’m not brave enough to say. I know.

Soon after, I began to ignore the long hair that marked me so firmly as a girl, leaving it in the same ponytail for days on end, until it knotted into a solid, dark mass. All my friends were boys, and my dearest hours were spent playing Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles on the lawn with my twin brother and the neighbor boy. My room was blue, and my teddy bear was blue, and the turtle I wanted to be was Leonardo, not only because he was smart but because his color was blue. When my twin brother got something I didn’t—to go to the baseball game, though we were all fans; to camp with the Boy Scouts while my sisters and I were shuttled off to the ballet; to keep the porn mags I discovered in his bedroom—and the reason given was that he was a boy, rage choked me with tears. That was grief, I think now, the grief of being misunderstood.

One afternoon, when my brother yet again went shirtless for a game of catch and I wasn’t allowed to, I announced to my father that I didn’t want to be a girl, not if being a girl meant I had to wear a shirt. My father went to get my mother. They whispered together, then my mother explained that I should be happy to be a girl—there were so many good things about it. I knew there were; that wasn’t the problem. The problem was that people kept calling me one. I remember realizing I couldn’t explain this to her.

Back then, in 1985, the word genderqueer—how I now identify, the language that would eventually help me see myself—hadn’t yet been invented. The term wouldn’t come into existence for another decade, nor would nonbinary, which first appeared in an online forum: “Do you ever really feel as if you’ve moved from that nonbinary existence as a transsexual into a real man or woman?” Note the way nonbinary was positioned from its inception as transitory, as a passing through. It could not itself be a destination, the end to a story. As the scholar Jay Prosser has written, “transsexuality is always narrative work, a transformation of the body that requires the remolding of the life into a particular narrative shape.” It is the narrative constructed in retrospect—perhaps even more than the body—that makes the self recognizable, even cognizable. But narrative requires language. What word was there for me then that could have conveyed the wrongness of everything?

So I said nothing. In middle school I looked up and realized that everyone had chosen sides. The girls suddenly wore makeup and sparkles. The boys no longer played with them. Not choosing sides meant everyone would see that you were other. By then I already felt so other I couldn’t bear it. And so the years of frosted pink and purple eye shadow began, and the earrings I bought in packs at Kmart, my favorite a pair of tiny turquoise dangling airplanes. In girl or boy or neither form, I have always been a fan of excess.

At eighteen, I admitted to myself that it was the girls who caught my eye, not the boys. Terrified, I kept this, too, a secret, and kept dating boys until, at twenty-eight, I met a woman who pursued me. In her, I chose—as I would keep choosing—the sort of woman who made me feel safe. They wore long earrings like I did; sometimes we traded glitter eye shadow, and when we went to bars together we were at once highly visible and utterly invisible. Men asked if we were sisters. They bought us drinks.

All of this felt like fakery even as I lived it, my life arranged into a role like those in the plays I did throughout high school. To live that way—to make your life suit a prearranged story, a gender—was possible.

Until abruptly it wasn’t. I was in graduate school when this changed, dating a woman who identified as butch and looked so much like a boy that the first time I went to meet her at a bar, I walked right by her on the street. When I stood with her I was always read as the feminine one; I was always safe; nobody knew my secret. I told my graduate school I was taking a leave of absence, moving to New Orleans to research a murder that I would eventually write a book about. I told no one that this was a lie; I already had the research I needed. I moved to figure out something I could not articulate even to myself, but that on some quiet level I had been wondering about since I was eight. My body did not feel like mine. My life did not feel like mine. Was there a self that wouldn’t feel like a costume?

Christine Jorgensen, 1953 © Tom Gallagher/New York Daily News Archive/Getty Images

I don’t know when I first learned of Christine Jorgensen, only that even decades after her gender-confirmation surgery, she was still my first image of what transgenderism, and transition, looked like. In the footage of her returning home to the United States from Denmark after her operation, in 1953, she steps off the plane in a thick, high-necked coat, her hair pinned up and curled just so beneath her hat, her heels smart and her stride strong. Once, she was a G.I., but now she stands flanked by uniformed officers, and no one would ever mistake her for one of them. She is a lady.

In front of a tall microphone, cameras flash. Her eyes are wide, searching. “I’m very impressed by everyone coming,” she says. But she doesn’t quite look impressed. She looks stunned. She turns her head left to right. Presumably it’s the cameras she’s looking at, the size of the crowd that has come to see her. But she also seems like she’s taking in the strength of the gender line she’s just crossed. Will there be a movie deal? a reporter wants to know. Perhaps the theater? What will Jorgensen do with her new body, her new notoriety?

“I thank you all for coming,” she says. “But I think it’s too much.”

Some fifty thousand words from the major wire services followed. The size of the hunger that greeted her showed how shocking her trespass was. “How does a child tell its parents such a story as this?” she mused in a letter from the time. To be born and considered one sex. To return home another.

After her, children did tell their parents stories like this, and slowly, painfully, a narrative spread, one that situated the transgender person as “trapped” in the wrong body—a confinement that could only be relieved by transforming into the other sex, the true self. By the Sixties, what was then called transsexuality was widely recognized. On November 21, 1966, a front-page article in the New York Times announced that Johns Hopkins was now performing sex-change surgeries at its new Gender Identity Clinic. By 1975, a nationally syndicated advice columnist was writing that a transsexual person “has the soma (body) of one sex and the psyche (mind) of another.” The goal of a sex-change operation was to make the two align, thus making possible the “ultimate goal” of the transsexual person—which, the columnist reassured his readers, “is to marry. This provides psychic confirmation that the change to the new sex has been complete.” In 2011, Janet Mock told Marie Claire that when she had had to live as a man, she “had lived with the sheer torment of inhabiting a body that never matched who I was inside, the one devastated by the quirk of fate that consigned me to a life of masked misery.” It was only once she’d crossed over fully—when she could finally live openly as a woman—that she could imagine a future. “No more dress-up,” she said. “No more pretending.”

In New Orleans, I stop pretending. The Boston girl who looks like a boy comes to visit me in the small apartment I have taken in the Irish Channel. I love the pink light over the streets each evening, the night-blooming jasmine scenting the air, even the splashed beer of the revelers from the bars on the corner. When I sit on my stoop reading at sunset a man rides by on a bicycle wearing a silver tin-man suit, a red felt heart pinned over his chest. As he passes, he doffs his oilcan hat. I raise my glass of wine. In the French Quarter I have seen trapeze artists in bars; I have seen goths dressed in their vampire black. In this city you can be anything you want to be.

Maybe this is what makes me brave. One night she and I are dressing to go out, her in men’s jeans and a long-sleeve T-shirt and me in a short black dress with puffy sleeves that I pair with cowboy boots. I have fixed my hair into pigtails even though I am thirty, going for some image of girlhood, emphasizing the difference between us. Flirting. I lift a silver flask to my lips for a swig of whiskey, and she snaps a photo of me right then. Looking at that photo now is like looking at the moment before.

“Can I try on your jeans?” I ask. The jeans with the button fly and the loose fit. Jeans like I have never before put on my body, afraid of how I might feel in them.

Does she flinch? I am too nervous to notice. She looks at me, long and steady, and says, “Sure.”

Then she snaps what is still the happiest photo of myself I have ever seen.

My memory is that when she lowers the camera this time, her face is grim. “We’re going to break up.”

I hardly hear her; I am peacocking around the apartment. Grinning giddily, turning this way and that in front of the mirror I usually avoid. This rightness, my God. It’s possible to feel this way?

“We’re going to break up,” she says again.

I tuck my smile away like folding up an outfit. “Why?”

She gestures from the jeans—her jeans—to my face. “Look at you. You’re not going to be happy as a femme anymore.”

“So?”

“I’m butch. I need to be with a femme. Besides,” I remember her sighing. “You’re going to start dating femmes, I know it. Two butches together wouldn’t be right. It would be like two femmes. That doesn’t make sense. The masculine and the feminine together, that’s how it should be.”

Soon I am alone again with my dog in the New Orleans apartment, and a pair of jeans I bought from the men’s department of Target without even trying them on. The fly comes up well past my belly button, the crotch sags, they fit atrociously—they are instantly my favorite thing I have ever owned. I buy a pack of men’s white ribbed tank tops and a pair of Converse with skulls on them, and I start dating a girl who wears flared skirts in all kinds of weather. I open all the doors and order all the beer and when we fuck I am only ever on top and I am only ever inside of her.

And I’m happy, sort of, except for the way that playing a butch role feels like performance, too.

So it is in New Orleans that I first type “ftm,” female to male, into Google, late one sleepless night, comforted by the blue light of my laptop and my dog snoring at my feet. Once I begin, the words I have never dared think before come in a torrent. I still can’t say them aloud, but I can type them at night when no one is looking. Transgender.Testosterone.Transition.

Lying on my back, a steady pour of whiskey at my side, I study the photographs that follow. The chests rendered flat with the scars from top surgery. The biceps and traps swollen with new hormones. The constructed dicks of bottom surgery—not a choice all, or even most, F.T.M. people make, but an option, the remolding of a body. The remolding of a life. I watch the footage of Christine Jorgensen over and over. Is this rebirth what I want? Is this what will finally make my life, and my body, my own?

Photographs by Rana Young from The Rug’s Topography, published in January by Kris Graves Projects © The artist

In the years that followed, I argued with myself over whether I felt trapped enough to truly be trans. Some days I would decide yes, and that I’d make the necessary changes to be recognized as a man as soon as I felt brave enough. Other days I would decide no—never because I didn’t feel trapped, but because I wasn’t sure being seen as a man was what would save me. It wasn’t that man felt right; it was that woman felt wrong, and what could be the alternative?

Four years of late-night googling passed before I could say any of this aloud. When I finally did, it was to a lover, a woman I’d fallen for the instant I’d seen her sitting in a crowd at a reading, her hair long and curly (like mine), her jacket black leather (like mine), her shoulders broad and tough as mine had never been. She was unabashedly she: hips that swung from side to side when she walked, lips plump and swollen, a lilting accent in her voice that drove me mad. On our first date she showed up in a tie, and I was so flustered and surprised I could scarcely speak all night. Wasn’t I supposed to wear the tie? I don’t think I said that. I hope I didn’t say that. But she must have sensed something, because for the years we were together, she never again wore one. Instead she donned the stilettos, the fishnet stockings, once a dress so tight, that rode so high under the curve of her ass, that I nearly followed her around the family party we were attending with a jacket. After we fought so badly we broke up, I found I could not stop thinking about her ass, her lips, the way when she straddled me in bed her hair swung in my face. The visions lasted for months, a haunting. Finally I sent a note unsigned in the mail—no name, just words of want. We met at a motel and still we didn’t speak. Just the white sheets, her breasts I’d missed so much, the black confection of string, knotted into the shape of a flower, that revealed itself when I pulled off her clothes. We fucked until we were sweaty and the sheets were sweaty and everything smelled like I was home again.

Maybe that’s what made me brave again. “I’m not. . . ,” I whispered, my fingers curled in her hair, my lips to the sweat of her neck. “I don’t feel like . . . I’ve never felt like. . . ,” and then finally, “I don’t think I’m a woman.”

And her, bless her, what did she do? She told me she knew, from the way she felt me swell under her tongue. She told me she could tell from how hard I got and how much I swelled. I didn’t have the body of a woman, she said. She’d known it all along.

Perhaps her response now sounds reductive, essentialist in the way she read identity in the contours of my body. But that’s not how her words felt. They liberated me. She was saying that biology need not be assumed as cold, incontrovertible fact that had nothing to do with behavior or want. Rather it, too, could be conceptually constructed, seen as reflective proof of who a person was. The body rewritten with the pen of identity. As the cultural historian Thomas Laqueur points out, the body is always interpreted. “The body itself does not produce two sexes,” he writes, let alone two genders. We created these categories. We named them. We drew—we draw—the lines that define them.

Until the late eighteenth century, only men were conceived of as a full gender. Women were understood as not-men rather than a category unto themselves—defined through difference, through lack. This extended even to the body: the ovaries understood as not-quite testes, with no name of their own; the vaginal canal understood as the inverted and undescended sheath of the penis. Laqueur argues that the telling of sex in Genesis—Adam creating Eve from his rib—need not have led to an understanding of a different category in the cultural imagination, only a difference of degree. What wasn’t quite a man was a woman.

If someone with female-looking genitalia behaved in a way that was more like a man—if she had the assurance understood to be the domain of men, if she wished to have a profession, like the writer George Sand or the artist Rosa Bonheur, if she wore trousers and seduced women—she was thought to be an androgyne or hermaphrodite. Her genitalia might look the same when examined by a doctor (as they often were and, one imagines, horribly), but the explanation then was that medicine itself just couldn’t yet see the difference. Her behavior was an amalgamation; her body therefore must be as well. Behavior, how one wished to live—the story began from this origin. Desire mapped itself onto the body.

I don’t ever want to deny the oppression and policing of that period. Yet the privileging of desire, of behavior, reminds me of the freedom I felt from that past lover’s response. After that night in the motel, we invented language of our own, stories spun from our bodies in bed. Neither of us had yet heard the term nonbinary, nor the term genderqueer. Our understanding of what trans meant was still beholden to the binary, and so neither of us could say, then, whether I was trans. Only that I didn’t feel like a woman. So I wasn’t one. She said my body was different, and I believe that, to her, under her touch, it was. In time, hormones would do the work of her tongue. In time, hair clippers and binders would do the work of her gaze. But back then it was her.

What she saw helped me see myself.

Three years ago, I went to get my headshot taken. I chose the photographer carefully. She takes conservative photos. When she asked whether I wanted makeup and hair, I said yes. I brought two ties to the photoshoot but then agreed to only a single photo in which I was wearing one. My hair was long then, and the stylist straightened it with a blow-dryer and a brush, and then individually re-curled each curl with a wand. The makeup artist applied lip pencil as close to my lip color as he could find. I became a facsimile of myself. I looked older. I looked harder. I looked for all the world like a true-crime writer from New Jersey, which is, I suppose, one version I could tell of my life.

The photograph that resulted appears on the jacket of my first book, which is a memoir. The name on that book is a name I don’t use anymore. The portrait is of me; it is deeply not me. The French psychologist and philosopher Jacques Lacan posited that it is in a child’s infancy that, upon encountering a reflection of themselves in a mirror or window, they are introduced to apperception, the idea that they themselves are not only a self but an object that is viewed and interpreted by others. In a way, the moment of recognition in the mirror is also a moment of splintering: from the private self to the self that is apprehensible to the other. This moment of alienation never resolves. There instead develops a state of subjectivity, a mediation by the outside world, an awareness of being perceived.

“Even in my own mind, I have erased myself,” the writer LaTanya McQueen muses, thinking of the times she has picked up a piece of fiction and begun to read it, and assumed all the while that the characters are white, when she herself identifies as mixed race. What does it mean not to exist in your own imagination? And what does it mean to live like that for so long that you assume it is the only way?

The headshot is a very expensive thing I will never use again. A very expensive monument to my last attempt to conform to a binary that never suited me. A monument to a change that took a long time to come and then arrived very swiftly and that I do not think will ever change back. When a dear friend who has known me only in the after—the way I look now—first saw the picture, they were silent a long time, so long that I thought they must be half-asleep or stoned or something. What was going on? The moment became awkward.

Then, finally, they laughed. “I’m sorry,” they said. “It’s just that I can see you’re in there somewhere, in that person, but. . . ” Then they laughed again.

What the photograph really is is a portrait of limited risk. I was trusting you, reader, with one story of my life. I was not ready to be open about another.

“Lachlan,” by Jenny Papalexandris, from Five Bells: Being LGBT in Australia, published by the New Press © The artist

Last March, I finally cut off my hair. I was in Sydney, on the other side of the world, and I made an appointment with a stylist whose cuts I’d seen on Instagram. I walked in and asked her to shear the curly hair that was well past my shoulders. Use the clippers, I said. For the first time in my life, I felt the buzz against my scalp. Afterward, I suppose I was in shock. I nearly cried. As I walked the streets, unsure where I was going or where I should go—unsure, it felt like, of this body I had found myself in—I passed a men’s clothing store whose window displays I’d admired days before. I went in. I left several hours later, holding two bags that contained nearly a month’s salary worth of clothing, neatly folded, suddenly loving the way everything looked on me. I wore some of that clothing on the plane home, twenty-two hours in a button-down shirt and stiff blazer. On two different continents, airport security called me “sir,” and then, seeing something in me on a second glance, “I’m sorry, ma’am.” I did not correct them either way. At home, I introduced myself to new people as “Alex” and asked them to use the gender-neutral pronouns they/them. I did not mention this to people who had known me for years, nor correct them when they called me Alexandria. My driver’s license had expired, so I went to the D.M.V. Waiting for my ticket number to be called, I snapped a photograph of my expired license, of the woman of ten years ago with her long, curly hair and her wide grin, her shirt falling off one shoulder to expose a bra strap, her dangling earrings. That woman would move to New Orleans one week later. Sitting in the D.M.V., I took a selfie: the skin of my scalp under the fade, my shirt buttoned to the collar, unsmiling. I posted it to Instagram together with the license. “Gender is a social construct,” the caption read.

At some point I realized that I didn’t and don’t believe in narrow rules of what counts as trans, and I don’t want to transition to a binary place where I would be perceived as male. For so long I thought that was the only other option, and then I was stuck, because that idea didn’t feel right, either. The only time I am ever emotionally attached to my breasts is when I imagine someone taking a knife to them. Yet binders leave me headachy, unable to breathe. I would love to change the countless small facial signifiers that lead people to sort me as female, yet doctors caution that it’s impossible to predict how the body will respond to even low doses of testosterone. It took me eleven years to decide to take that risk. Now I watch as my body slowly changes, monitoring, looking for the right point. I don’t want to pass as a man any more than I want to pass as a woman. I don’t want to be perceived as either. Because I am not either. I want to be seen.

I am far from the only queer person to have been liberated by a loosening of the binary. Janet Mock later disavowed the 2011 Marie Claire piece that described her as trapped, saying that she now understands her experience as more fluid than that. In March, the singer Sam Smith came out as nonbinary and cited a string of other celebrities whose visible examples had allowed Smith to envision a narrative for themself. Mattel recently released its first gender-neutral doll, citing the need for gender-nonconforming children to see themselves represented. Queer identities are a daisy chain of becoming, a passing-on of possibility.

I have come to think of the questions that followed my own becoming in terms of the number of drinks required for people to ask them. There are the one-drink questions, like, “So, do you prefer ‘Alex’ now? For everything?” or even, “Are you trans? Is this the beginning of a transition?” And then there are the questions that arrive only after a friend has embraced me, has sat across from me in a warm-wooded bar, has ordered one drink and then another. “I feel comfortable with you,” they sometimes begin, and smile at me or reach a hand across the table for a squeeze, affirming our intimacy. The words that come next never feel spontaneous, somehow, but mannered, as though they have been sitting just beneath the surface and are not for me, or not only for me, but for the changing times and language we live in.

“Because I feel comfortable with you, I trust I can ask you this. I haven’t had anyone to ask.” They sip. “I know I’m supposed to use gender-neutral pronouns for you now. But I’ve known you as a woman for such a long time. Am I really supposed to think of you differently now?” And then a moment later, after, perhaps, more steadying alcohol. “I mean, what am I supposed to think of you as?”

This is a risky political moment to identify as trans while questioning the universality of the narratives that have dominated the public imagination of transgenderism. In many parts of the country—more than ever before—binary trans people are finally recognized, able to tell a story of who they are, able to be seen. But under what the National Center for Transgender Equality rightly calls “the discrimination administration,” trans people are under unprecedented and terrifying attack: re-banned from serving in the armed forces and no longer necessarily eligible for health-care coverage, mental-health counseling groups, or admission to homeless shelters. Soon, the Supreme Court will decide whether people can be fired from their jobs just for being trans. This isn’t merely a rollback of civil-rights protections. It’s a war, an attempt to legislate a group of people out of existence by making it too precarious for them to live. Trans people, particularly trans women of color, already face high rates of violence: Hali Marlowe, shot to death on September 20 in Houston, Texas, was at least the nineteenth trans woman murdered just this year.

Under these circumstances, it’s difficult to say that the categories that have helped so many people be seen and see themselves—categories that are now threatened, that must be defended as legitimate—might still be too restrictive for some, like me. To ask not just for protections for those for whom the gender binary feels true, but also for those of us who have had to find language that transcends it. To ask for, and claim, language of our own.

That language takes time. Recently a new acquaintance stopped me in a stairwell. “You had more hair when we met,” he said. His tone was friendly, but I was immediately wary. I didn’t just have less hair. I dressed differently. I went by a different first name. I used different pronouns and had asked my workplace, my insurance, and my landlord to recognize that. Soon, I knew, I would start to look subtly different, the hormones doing their work. I understood the subtext, what he might really be asking. “When did you decide to cut it?”

How could I answer? What few words would convey the complexity of a life? I had decided with every step away from the binary, every step toward being comfortable with myself. We’ve never had a narrative for who I am, but I am trying now, trying with language, trying to tell this story in a way I and others can understand, a way that figures the middle as the destination. I thought back to the child I was, the one who knew that girl didn’t quite fit, who liked the look of boy and couldn’t yet know that that wouldn’t quite fit either, the child who didn’t have the language and would need to write and live and feel a way into it, wait for society to invent the very words that would allow them to be seen.

All I said was, “When I was eight.”