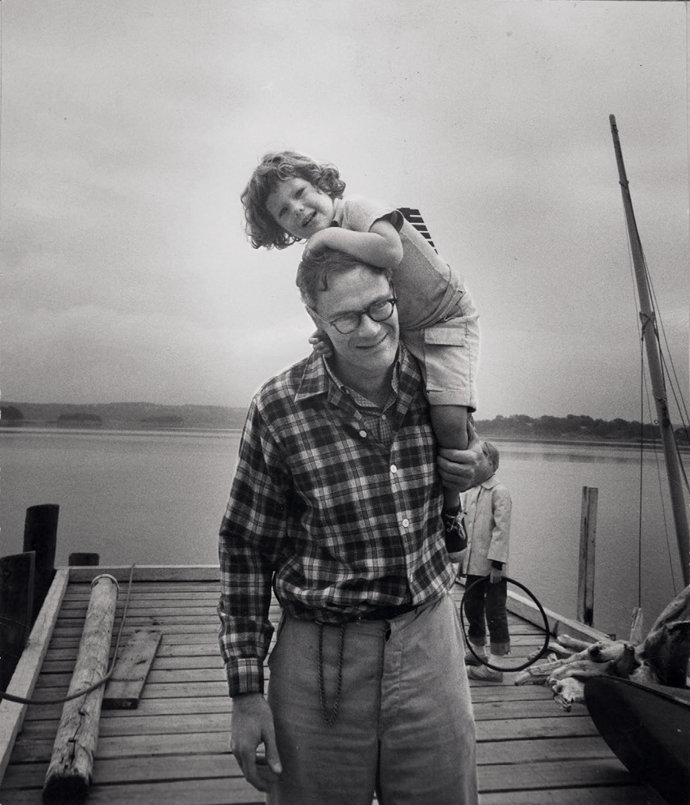

Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Hardwick. Photograph courtesy the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

Discussed in this essay:

The Dolphin Letters, 1970–1979: Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert Lowell, and Their Circle, edited by Saskia Hamilton. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 560 pages. $50.

The Dolphin: Two Versions, 1972–1973, by Robert Lowell, edited by Saskia Hamilton. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 224 pages. $18.

In 1970, Robert Lowell moved to England to take up a brief residence at Oxford’s All Souls College, leaving his wife, the brilliant writer Elizabeth Hardwick, and their adolescent daughter, Harriet, in New York City. To Hardwick’s increasing uneasiness and fear, he stayed on in England: eventually she learned that he had begun an affair with the writer Caroline Blackwood, a member of the wealthy Anglo-Irish Guinness family. In The Dolphin (1973), his penultimate volume of poems, Lowell relates, in a series of sonnets, his affair with and eventual marriage to Blackwood, by whom, as the titular Dolphin, the poet was “swallowed up alive.” Within his sonnets, Lowell embedded sentences and phrases from Hardwick’s letters to him, written after she learned of the affair, including her initial indignant and distressed responses.

The Dolphin caused a stir both before publication and after. Some of the friends to whom Lowell sent the draft (including Adrienne Rich and Elizabeth Bishop) replied with instant objections: “Art just isn’t worth that much,” Bishop wrote in her letter. Bishop was shocked not only by Lowell’s quoting Hardwick’s letters without her knowledge or permission, but also by his mingling of fact with fiction. In response to those criticisms, Lowell made some attempt in revision to render the quotations more anonymous and to rearrange the sequence, but to no great effect. While The Dolphin basically remains a nakedly autobiographical document (“one man, two women, the common novel plot,” as its author ironically described it), it is written in an ambitious style: traditional in its use of a fourteen-line unit, relatively unconventional in its unrhymed form, and most original in its rapid shifts in registers of language—now colloquial, now densely allusive.

Most of the letters Hardwick wrote to Lowell between their marital separation, in 1970, and his death at sixty, in 1977, disappeared from Lowell’s papers, leaving a conspicuous gap in the record of those years, a tumultuous and crucial period. But two new and unexpected volumes—expertly edited and with wonderfully informative footnotes by the poet and scholar Saskia Hamilton, who also provides an alert and balanced introduction to each—have now been published.

The first—The Dolphin Letters, 1970–1979—contains Hardwick’s 102 “missing” letters and explains their disappearance. At Lowell’s death, they remained in the possession of Caroline Blackwood Lowell, who subsequently entrusted them to Lowell’s close friend the poet Frank Bidart, with the proviso that they were not to be published until after Hardwick’s death. Bidart eventually deposited them in Harvard’s Houghton Library, and with the permission of Lowell’s children from both relationships, Harriet and Sheridan, they have now appeared. The book also includes Lowell’s responses to Hardwick and some of his letters to friends concerning the poems.

The second of the new books—The Dolphin: Two Versions—contains the 1973 published version as well as the original 1972 draft Lowell had sent to friends, reproduced from a typescript made by Bidart (who had gone to England to assist Lowell in editing and sequencing the poems). The typescript is accompanied, en face, by the intermediate changes Lowell dictated to Bidart and Blackwood as he reviewed the draft before circulating it, an excellent source for any reader interested in Lowell’s stylistic evolution between 1972 and 1973.

The Dolphin letters illuminate Lowell’s life and aesthetic perplexities in his later years, but they are equally useful in unveiling Elizabeth Hardwick’s unforgettable role during that era. Lowell’s and Hardwick’s letters are supplemented in this volume by others written by members of their circle of friends, including Bishop, Rich, and Mary McCarthy (Hardwick’s principal confidante), which flesh out the New York life of Lowell, Hardwick, and their daughter, Harriet, in the Seventies, as well as the life in England of Lowell, Blackwood, and their son, Sheridan. The collection, as the publicity notice from Farrar, Straus and Giroux says, “has the narrative sweep of a novel.” (I once asked Lowell why he so liked the poems of Thomas Hardy: he said, “Because they’re about real men and women, and the relations between them.” Both he and Hardwick, in this late correspondence, refer to Hardy’s remorseful poems to his first wife after her death.)

Although I knew Lowell during the last three years of his life, I did not know Hardwick, except for our having been a few times at the same event; we never had a conversation. When I asked Lowell why he appropriated Hardwick’s own words, he said that, to represent her fairly, he thought she should speak for herself, rather than his speaking about her. For me, the “lost” letters testify to Hardwick’s extraordinary depth of character and faithfulness to the past years of love between herself and Lowell: though not without faults (she was jealous of Bidart’s instinct for Lowell’s poetry, for instance, and she could lose her temper), she must have been one of the sanest and most generous women who ever lived. After the initial blow of learning from friends about her husband’s affair and writing letters that Lowell characterized as ones that “veer from frantic affection to frantic abuse,” she regained her equilibrium and for the remaining several years of Lowell’s life made every effort to preserve their daughter’s good relations with him. She insisted to Lowell on Harriet’s right to her father’s regard and interest, and her forceful representation of that right meant that Harriet could see her father on both sides of the Atlantic and correspond with him, without fearing objections or hostility from her mother. Lizzie (as Lowell always called her) went so far as to write Caroline in anticipation of one of Harriet’s visits to England, so that all should go smoothly.

But these are not the most impressive aspects of the Hardwick correspondence: what strikes the reader is how Lizzie, after the first shock, wrote steadily and benevolently to Cal himself letters of both love and friendship. (Lowell was called Cal by those close to him.) After an initial stiffness of address (“Dear Cal”), the letters revert to their usual “Dearest Cal” and “Darling,” and Hardwick’s early pained and painful reproaches are not repeated. Although Hardwick confesses to loneliness while in their house in Castine, Maine, when Harriet is at summer camp, in New York she occupies herself with caring for Harriet and making their joint life as happy as possible. (Later she would also teach, work that included tiring commutes from New York to Smith and the University of Connecticut, as well as a regular stint at Barnard.) During the separation from Lowell, when no clear arrangement for their finances existed, she worried about money, but after the division of goods in their 1972 divorce agreement, she was reassured. The old friendship between herself and Lowell even survived a heated exchange over rights to the house in Castine, begun when Blackwood intervened, asking (with no legal basis) whether it should not go in part to her son Sheridan.

One cannot but admire Hardwick’s insight into her daughter’s sensibility and gifts. Because of Harriet’s uneven high school performance at Dalton, Hardwick expended time and effort in looking into other schools, both in the United States and in England (where it seemed possible, before she learned of her husband’s affair, that she and Harriet would join him). She came quite rapidly to realize that criticizing her adolescent daughter’s indifference to (or rebellion against) school was an error, and relied rather on her sympathy for Harriet in her sadness (with her father absent, and with no siblings or close relatives at hand). Lizzie’s wisdom in allowing Harriet freedom from the frenetic cultural pressure for children to excel in secondary school was (and remains) a rare parental kindness.

When Lowell’s marriage to Blackwood—made disastrous by Caroline’s inability to cope with his manic-depressive illness and her own worsening alcoholism—reached its final, catastrophic phase, it was to Hardwick that Lowell turned. She agreed to let him come back to live with her—not as a husband but as a companion and friend. In 1977, they spent an agreeable summer together in Castine. When Lowell flew to Ireland to visit his young son, the tempestuous interaction with Blackwood became intolerable, and he flew back early to New York, dying of a heart attack in the taxi that was taking him from the airport to Hardwick’s apartment.

Then, in another act of selflessness, Hardwick allowed Blackwood, after the Boston funeral and the New Hampshire burial, to stay with her in her New York apartment to await the memorial service. Hardwick reported on the funeral and burial to Mary McCarthy:

That was the end. But it was the beginning of a nightmare here for me. Caroline somehow moved in with me for 8 days and nights to prepare for the Memorial Service. I don’t think any single night I slept for more than two hours. Her poor drunken theatricality hour after hour, day after day, night after night was unrelieved torture for me and I am sure for herself much more. Somehow she has put herself beyond help and sadly for her all help begins at the same spot—to stop drinking, at least for today, tomorrow, for a week, an evening.

During all these burdened and disrupted years, Hardwick was writing. The emotions generated by the Blackwood affair and subsequent marriage prompted deeply disenchanted reflections on modern relations between men and women. Hardwick published the resulting essays in The New York Review of Books (collected in 1974 under the title Seduction and Betrayal), and Lowell felt that they were revelatory, in part, of their mutual suffering: “Liked and immensely admired your Ibsen, maybe rawly near home. Or is it? . . . I think you should be vain of having put so much of yourself into the classic plots; I’m envious.” Hardwick’s essay “The Rosmersholm Triangle” combines psychological description with fraught expression, and is even more intense than other essays in the volume:

It is Ibsen’s genius to place the ruthlessness of women beside the vanity and self-love of men. In a love triangle, brutality on one side and vanity on the other must be present; both are necessary as the conditions, the grounds upon which the battle will be fought. Without the heightened sense of importance a man naturally acquires when he is the object of the possessive determinations of two women, nothing interesting could happen. . . . The triangle demands the cooperation of two in the humiliation of one, along with some period of pretense, suffering, insincerity, or self-delusion.

“Rawly near home”—Lowell’s judgment—betrays his own hurt. And his comment that Hardwick “put so much of [herself] into the classic plots” points to her force as a critic. She so enters into the psychology of literary characters that she draws the reader pell-mell into their erratic orbits and irrational decisions. She is less interested than some literary critics in an analysis of authorial technique; what she is after is creating for her reader an immersive plunge into the imaginative results of that technique on the page. She never doubts the genius of her authors, and her attention to their power transfers itself into the reader’s mind and heart.

Robert Lowell with his daughter, Harriet. Photograph courtesy the Harry Ransom Center

In “Epilogue,” the poem that closes Lowell’s last book, Day by Day (1977), the poet asks the tragic (and defiant) question: “Yet why not say what happened?” Through all these letters, both he and Hardwick puzzle over “what happened” to break their long marriage. To understand the unwise episode with Caroline, it must be remembered that Lowell had suffered since youth from bipolar disorder, which recurred—almost yearly—as a destructive elation followed by a desolate depression. During their twenty-one years of marriage (1949–70), Hardwick had seen Lowell through all his instances of illness, coping with the onslaughts of mania (including a frequent conviction that he had found a new beloved) and enduring with him his gradual, saddened recovery. Her earlier description of her life with Lowell (written to Lowell’s first biographer, Ian Hamilton, and reproduced by Saskia Hamilton in The Dolphin Letters) conveys the pattern of their married existence:

Cal’s recuperative powers were almost as much of a jolt as his breakdowns; [that] is, knowing him in the chains of illness you could, for a time, not imagine him otherwise. And when he was well, it seemed so miraculous that the old gifts of person and art were still there . . . Then it did not seem possible that the dread assault could return to hammer him into bits once more.

He “came to,” sad, worried, always ashamed and fearful; and yet there he was, this unique soul for whom one felt great pity.

Their happiness between his mental collapses had many sources: their mutual vocation as writers; their joy from daily conversations in which Lowell’s poetic intelligence met her critical wit; their similar political convictions and activism; and, after Harriet’s birth, their love for their daughter. At a time when lithium was thought to be a potential cure for manic-depressive illness, it must have seemed to Lowell, who began taking it in 1967, that he might at last be able to have a “normal” marriage, one that would not require his wife to be nurse and keeper.

Lowell had met Blackwood in the Fifties in New York through the editor Robert Silvers, who suggested in 1970, as Lowell was leaving for England, that he might like to get in touch with her. According to the closing poem in The Dolphin, at their first meeting in London as guests at the same party, Blackwood (then married to the composer Israel Citkowitz and the mother of three daughters) “made for [his] body,” bringing him back to her house:

When I was troubled in mind, you made for my body

caught in its hangman’s-knot of sinking lines,

the glassy bowing and scraping of my will. . . .

And so the affair began and progressed, with Lizzie knowing nothing for some months. Yet their correspondence persisted, on through the affair; Blackwood’s pregnancy; the subsequent marriage; the birth of Sheridan; and the years of his early childhood. From England, Lowell addresses Hardwick (as he usually did) as “Dearest Lizzie,” and affirms his inability to do without her, even in absence:

I yearn for your letters, and hope you won’t give up the habit. I have always prayed I were two people (one soul) one here, one with you.

I miss you always to joke with, reason with, unreason with . . .

Hardwick’s ability to maintain her care and compassion (and letters) while Lowell was with Caroline is matter for admiration. She even visited them in England, in 1976: Lowell comments, “It was so strange seeing you and Caroline easily (?) together, that I almost feel I shouldn’t refer to it.” During Lowell’s time in England, Hardwick was a single mother, maintaining a complex New York literary, political, and familial life even while overwhelmed with financial uncertainty. She was filled with anxiety at Lowell’s long silence at the outset of the affair, and angry and heartsick when she learned of it. And even more admiration rises in the reader as Hardwick—on hearing that Lowell is hospitalized for mania in London and that Blackwood, frightened, has fled—flies to England together with their friend Bill Alfred to take care of her isolated, ill ex-husband, who had ceased to take his lithium. There is scarcely a virtue that Hardwick is not seen to exemplify in these years, as witnessed in her description to Mary McCarthy of the hospitalized Lowell:

He has given up lithium, of his own will . . . It has always seemed improper to me that he should appear so old, walk so slowly, when lithium is not supposed to be a downer in that sense. . . . I feel nothing but a groundless hope for him at the moment.

These letters don’t match the inventiveness of those exchanged by Lowell and Bishop, when each had only to entertain the other and sympathize with troubles from afar. And, at first glance, the voyeuristic interest offered by the living drama of the messages between Lowell and Hardwick almost outweighs their nature as letters. But neither can put a foot wrong in writing a sentence; each has the instinctive cadence of a born writer, the sophistication of an adult who has seen and felt almost too much, the directness and candor of an intimate acquaintance, and the steady capacity for irony even in sadness. Hardwick’s loyalty is so great that one reads with some surprise her self-description to the absent Lowell: “I look back on my own life of intense anxieties whose cause I have no memory of mostly. And yet one is given his own quivering self, at birth I suppose.”

These letters, written as they were in the stormy Seventies of social unrest, show both Lowell and Hardwick responding with outrage and anguish to the war in Vietnam, the invasion of Cambodia, and the shooting of unarmed students at Kent State by the National Guard. “The unbearable and brutal news” (as Lowell characterized it in a letter to Peter Taylor) also included Watergate. But the fairly predictable political comments are less interesting, to my mind, than the personal ones. Learning that the manuscript of The Dolphin has been sent out to friends, who are writing to Lowell criticizing his quoting of “Lizzie’s” letters, Hardwick unexpectedly tells Mary McCarthy that she is annoyed at the friends:

I cannot imagine anyone else of Cal’s gift and thirty years of writing and publishing being sent telegrams, letters of plea about his work. . . . I can’t see that I can be hurt . . . I truly feel indifferent to it all. Credit or discredit is entirely his. I have written him that I don’t care a fig.

This may be too defensive (the gamut of feelings is part of the appeal of the correspondence), but at least it reveals Hardwick’s immediate response to Lowell’s circulating the manuscript; later, on actually reading The Dolphin herself, she felt, understandably, that Lowell’s selective quoting misrepresented her. She wrote a stiff letter to his publisher Robert Giroux objecting to his not obtaining her permission in advance.

The Dolphin itself—though uneven—conveys Lowell’s astonishment that in his mid-fifties he has fallen passionately in love with Blackwood, a woman fifteen years younger. He chose to forsake his earlier aspiration to religious or aesthetic transcendence in favor of the sensual and earthly sort—a choice already voiced in “Obit,” a sonnet addressed to Lizzie that had closed the 1970 Notebook, quoted here in a later, revised version:

Our love will not come back on fortune’s wheel—

. . .

Before the final coming to rest, comes the rest

of all transcendence in a mode of being, hushing

all becoming. I’m for and with myself in my otherness,

in the eternal return of earth’s fairer children,

the lily, the rose, the sun on brick at dusk,

the loved, the lover, and their fear of life,

their unconquered flux, insensate oneness, painful “It was. . . . ”

After loving you so much, can I forget

you for eternity, and have no other choice?

The opening of the first sonnet, “Fishnet,” in the published version of The Dolphin emphasizes the poet’s surprise at the entrance of a new and seductive woman:

Any clear thing that blinds us with surprise,

your wandering silences and bright trouvailles,

dolphin let loose to catch the flashing fish. . . .

Lowell’s original version of “Fishnet” had opened ineptly, in a rush of uncoordinated images:

Any clear thing that holds up the reader—

the line must terminate, the bright trouvaille,

the glitter of the Viking in the icecap.

As the sonnet flounders further, the Viking becomes a gold “colossus,” with “archetypal girth.” At last, the poem finds its way to its conclusive, published form, ending with a self-elegy that softens its modernized Horatian “bronze” with a touching gratitude:

The line must terminate.

Yet my heart rises, I know I’ve gladdened a lifetime

knotting, undoing a fishnet of tarred rope;

the net will hang on the wall when the fish are eaten,

nailed like illegible bronze on the futureless future.

“I have made a monument more lasting than bronze,” Horace had said of his own writing, but Lowell, correcting him, sees the eventual unintelligibility of all cultures, all bronze monuments. Yet even unreadable texts—cuneiforms, hieroglyphics, glyphs—declare (even before they are decoded) the solid existence of the past.

Poem by poem, the revisions of 1972 into 1973 vary in interest, but since each revision of language intimates a revision of thought, none are without significance. The language of vacillation, which dominates the sequence, continually reconstitutes itself from joy to self-reproach, from choice to indecision. Sometimes almost the whole sonnet is scratched out, when details become inert or too revealing. I quote the following “realistic” lines, with Lowell’s intermediate edits in brackets, from the 1972 draft; they are altered in publication precisely for their surplus of realism—too nearly resembling Blackwood and Lowell:

We totter off the painter’s platform,

the naked departure of the artist’s model

is cloaked by her Anglo-Irish elevation.

White rum is undetectable from tears.

We’re done, my clothes fly into your borrowed suitcase,

the good months are [day is] flown, and this [it] too goes

in my ragbag of private whim and illusion

dubiously flung together on

my single self-dramatizing character.

Like a cat painfully backing down a tree,

unalterably divorced from choice by choice,

I come on walking off-stage backwards.

The artist’s Anglo-Irish model and her rum disappear in revision (Lowell’s revisions were almost always for the better), and man and wife are transformed into actors on a stage:

And we totter off the strewn stage,

knowing tomorrow’s migraine will remind us

how drink heightened the brutal flow of elocution. . . .

We follow our script as timorously as actors,

unalterably divorced from choice by choice.

. . .

It’s over, my clothes fly into your borrowed suitcase,

the good day is gone, the broken champagne glass

crashes in the ashcan . . . private whims, and illusions,

too messy for our character to survive.

I come on walking off-stage backwards.

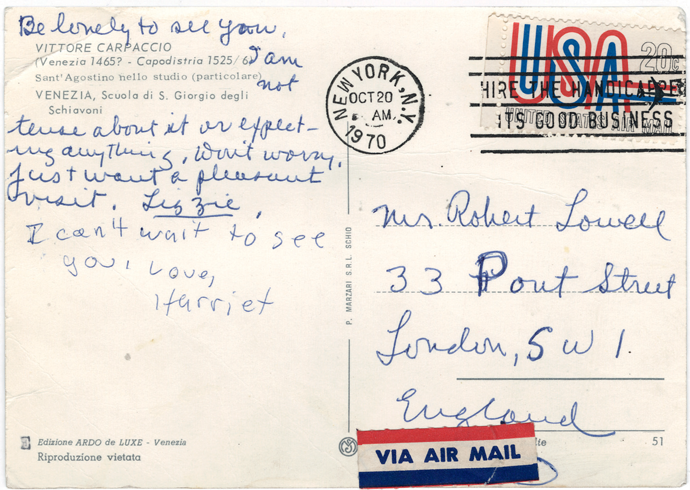

Postcard written by Elizabeth Hardwick and Harriet Lowell, from the Robert Lowell Papers at the Harry Ransom Center © Elizabeth Hardwick. Courtesy the Wylie Agency LLC

Some of Lowell’s revisions are made for sound (“glass / crashes in the ashcan”), some for visual drama (as “the painter’s platform” becomes “the strewn stage,” inhabited by “actors,” serving to connect this sonnet to “Plotted,” in which “Cal” sees himself as Hamlet: “I feel how Hamlet, stuck with the Revenge Play / his father wrote him, went scatological / under this clotted London sky”). And some revisions correct absurdities of the previous self-portrait—the cat “painfully backing down a tree.”

One wonders, reading The Dolphin afresh, whether the agitation over the quoting of personal letters without the consent of the writer will persist into the future. In the long view, no; the passing of time makes the personal irrelevant (Who was Shakespeare’s Young Man? Who was the Dark Lady?). But if we substitute ourselves for Hardwick in the moments of grief and desperation, we cannot take the long view. The virtue of her intelligence is that it does examine both views, short and long.

When I asked Lowell why he didn’t simply keep The Dolphin to himself, letting it be published on his death, he said that if he kept it, he would have had to continue to compulsively revise it and would not have been able to write new poems. To Bishop, he wrote: “I couldn’t bear to have my book (my life) wait hidden inside me like a dead child.” (“Hidden” is then struck through.) Throughout the sequence, Lowell castigates himself, questions himself, debates himself, condemns himself, excuses himself: there is no end to self-revision during his years of “the water-torture of vacillation.” But does an acceptance of midlife stasis in a long marriage implicitly constitute a way of being dead? He answers his own quandary: “I too, / because I / waver, am counted with the living.”

A few years later, in the free-verse poems of Day by Day (1977), the whole divagation into Caroline’s world is described more elegiacally, mythologized into a fable of Ulysses and Circe, and loosened into taking notice of the everyday, no longer subjected to the strict compression that dominated (not always happily) Lowell’s sonnet writing between 1967 and 1972. “Epilogue,” closing Day by Day, stands up for the inclusion of the brute factuality of “a snapshot” in the modern lyric, even though Lowell—like everyone else in his generation—had been educated in taste by the “caress” of the painter’s hand on canvas rather than by the haphazard grouping of the photographer. “Rough Slitherer in your grotto of haphazard” was one of “Cal’s” descriptions of “Caroline” in The Dolphin, the general disorder of her decaying sixteenth-century manor house in Kent seeming to stand for her refusal of bourgeois convention. Lowell’s eventual return to Hardwick, and his almost shamed gratitude to her for permitting him to come back to a life led in common, put a post hoc frame around the dramatic vicissitudes and fantasies of the flight to Blackwood. In Day by Day, which appeared in the year of his death, Lowell published a critique-by-hindsight of the midlife passion recorded in The Dolphin and the letters surrounding it—a passion that he both regretted and was unwilling to lose.