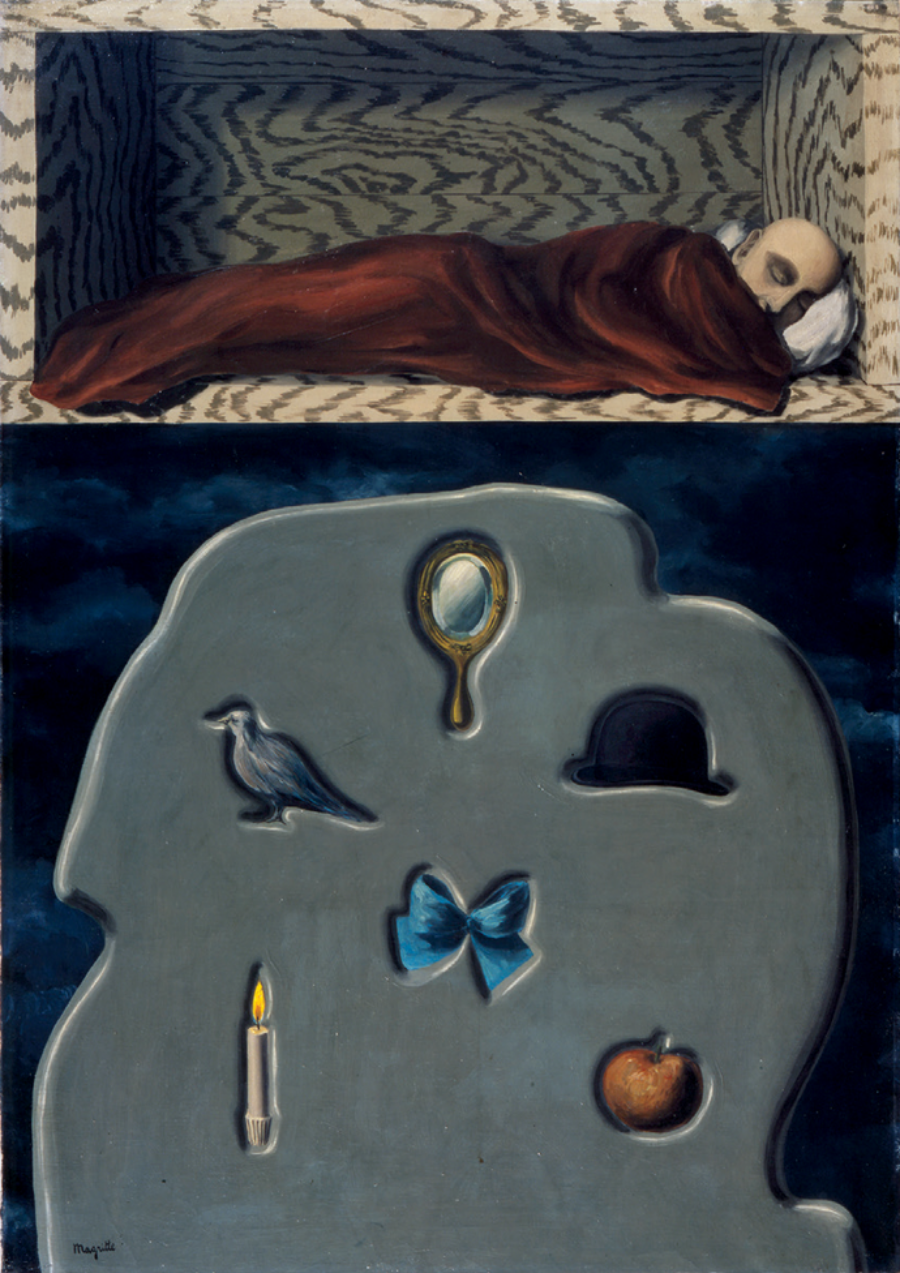

The Reckless Sleeper, by René Magritte © 2019 C. Herscovici/Artists Rights Society, New York City/Tate, London/Art Resource, New York City

The Interpretation of Dreams

It is 1924. Günter Zeitz is thirty-three years old. His hair is black, unruly. And, in the manner of certain very tall men, he habitually hunches his shoulders and lets his head hang forward. He is standing on a street corner in Vienna, where he has just bid good day to Professor Freud and introduced himself.

“Perhaps you remember me?” Günter says. “I wrote to you several months ago. I was working with Dr. Mohr.”

This encounter is not an accident. Günter has come to Vienna from Coblenz specifically to meet the Professor, and a friend told him that Freud passes the corner of Hörlgasse and Liechtensteinstrasse every day after lunch.

At the name Mohr, the Professor’s lip twitches impatiently under his yellow-stained mustache. “Did you not get my response?” His speech is impeded, as if he has a walnut in his mouth.

“Yes. I appreciated your prompt—”

“Then why are you here? Mohr is not a psychoanalyst.” The Professor lisps. He has to work to pronounce his s’s and r’s. “There is nothing I can do to help you.” Freud is carrying an umbrella, the point of which he lifts from the sidewalk as if to strike Günter on the shin. Just over his shoulder the black spires of the Votivkirche rise like a pair of demonic spruces.

“I entirely agree!” Günter says.

The Professor lowers his umbrella and tilts his head back to an angle that could make it seem as if he were looking down on the younger man. In fact, he is looking up. Freud is short, and skeletal inside his rumpled tweed suit. His eyes are gelatinous pools of amber and white within the black rings of his glasses.

“He is superficial,” says Günter, his voice trembling, his mind whirling. “He has the best intentions, but . . . You are right: superficial. Intellectually. I knew that I had nothing to learn from him.”

“His distinction between my work and Ferenczi’s is absurd!”

“Yes,” says Günter. “Absolutely.” In fact, Günter has no idea what Mohr has said about Freud and Ferenczi. “When I read your Interpretation of Dreams, I felt that I understood the working of my own mind for the first time—how everything is connected, I mean. Our perceptions, thoughts, instincts, memories, fantasies. The past and present. And language, of course—puns! Everything is connected to everything else. All my life, I have had the sense that nothing is really what it is—from a linguistic point of view, I mean.”

“Linguistic?” The Professor has taken a cigar out of his breast pocket and is searching his other pockets for a match.

“I mean that language and logic oversimplify reality. The dictionary in conjunction with the grammar book make it seem that a stone is nothing but a stone. Whereas a stone is always also something to kick or climb or walk upon; a weapon, the foundation of faith, the image of courage, fidelity, coldness of heart. A thousand other things! And all of them at once! The poets know this, especially the French poets. Rimbaud, of course. And Reverdy. But not the philosophers. Wittgenstein. Do you know Wittgenstein? You must know Wittgenstein—he’s from here. A brilliant man. But also stupid. But my point is that you defy him. You speak what he consigns to silence.”

Günter hardly knows what he is saying, and wonders if the Professor thinks he is insane.

Freud grips the cigar between his teeth. He holds a lit match up to it and sucks. Ragged wreaths of smoke obscure his face.

“Excuse me,” says Günter, “I’m babbling. It’s just that I’ve always felt—instinctively, I mean—that the world is a massive tangle of actualities. And your book helped me see clearly what I had never been able to articulate for myself.”

“Young man,” the Professor says between one long puff and the next. “What did you say your name is?”

“Zeitz. Günter Zeitz.”

“And what is it that you want, Zeitz?”

Günter’s mouth is entirely dry. His palms are wet. “I want to be a psychoanalyst, and I am hoping you will train me.”

“You understand that your training will consist primarily of your own analysis? Five days a week, an hour a day. Is that agreeable to you?”

“Of course.”

“Do you have the money?”

Günter hesitates a half-second. “Yes, of course.”

The Professor looks up at him with a wry smile and releases a long plume of smoke that, intentionally or not, blows into Günter’s eyes. The Professor then quotes his hourly fee. Günter blanches. The Professor laughs.

After a long silence Günter asks in a low voice, not meeting the Professor’s eye, “Would my analysis be with you, Professor?”

“Of course!”

There follows another long silence that Günter ends with a forced smile and the words, “Nothing would make me happier.”

He knows that what he has just said is the absolute truth. He has been dreaming of being analyzed by Freud practically since he arrived in Heidelberg to start university. But as they shake hands, he can’t help but feel that everything about their exchange has been utterly false.

Günter Zeitz is playing tennis on a sandy beach, but the net is composed of ripped shreds of corrugated steel, rusted pipes, tangled bridge cables, a gutted furnace. He cannot see his opponent, and he cannot hit the tennis ball over the net. Someone is shouting at him, urgently—warning him, perhaps—but in a language he cannot understand. “What?” he keeps saying. “What are you talking about?” Now he is no longer playing tennis. He is hanging from a kite high in the sky, or perhaps he is the kite, and a rope descends from him to a tiny figure on the beach—so tiny that Günter has no idea who that person is. And, in fact, the rope whips and swirls as if it were adrift in empty air. But Günter does not fall. He watches the foam of silent waves sliding up the sand, and the streak of the sun’s reflection on the rippling water. Where that reflection collides with the horizon, the sky breaks away from the sea. Inside the widening gap, Günter sees enormous machines—but not clearly. It is too dark. The darkness inside the gap is like a thick, brownish gas.

Günter smells something burning. When he cranes around on the couch, he sees the Professor, eyes closed, resting his head against the wall, his chin cupped in the palm of his left hand. His right hand dangles limply off the arm of the chair and a cigar lies on the carpet, where it is burning a hole. “Professor Freud!” Günter calls. The Professor sits up suddenly, apologizes, then bends to pick up his cigar, as if he has placed it there intentionally. He looks at it, grips it between his teeth, and takes a meditative drag. Smoke pours out of his mouth in a yellow-gray wave.

The Professor is dying, but he does not know he is dying, or he does not believe it, or he will not allow himself to know everything that death actually is. Six months before his sidewalk encounter with Günter, the Professor had his palate and the right half of his upper jaw removed to halt the progress of his cancer. An ill-fitting prosthesis of hard rubber edged with false teeth was inserted into the resulting cavity so that he might eat and talk.

Invariably when Günter steps into the foyer of Freud’s apartment, the previous patient, a slender, dark-haired girl of twenty, is standing in front of the coat hooks getting ready to go down to the street. Her face is long and her chin is off-kilter, as if she fell when she was a child and it was knocked slightly to the left. But there is a dart of tension at the center of her brow that makes her impossible to ignore. Günter always says “Hello” when he first sees her and “Excuse me” as he reaches past her to hang up his coat. While she is careful to move out of the way of his arm, she never says a word or meets his gaze. Only when she is actually stepping through the door does she turn and look him in the eye, her thin lips a tight, straight line, her black eyes radiating an emotion that sometimes seems to be irritation, sometimes uncertainty, and sometimes abject fear.

Sigmund freud: God has made them in the image of His own perfection; nobody wants to be reminded how hard it is to reconcile the undeniable existence of evil . . . with His all-powerfulness or His all-goodness. The Devil would be the best way out as an excuse for God; in that way he would be playing the same part as an agent of economic discharge as the Jew in the world of the Aryan ideal. But even so, one can hold God responsible for the existence of the Devil as well as for the existence of the wickedness which the Devil embodies.

Günter is standing on the sidewalk talking to Anna Freud, whom he finds pretty in a humble and entirely unstudied way. She is four years his junior and he sometimes thinks he should be attracted to her. But he is not. “He refuses to go back to his doctor!” she says. “He seems to feel that this one operation has cured him.” A tremulous fluid glimmers along the rims of her dark brown eyes. Her mouth is open, lozenge-shaped, as if she can’t get enough air. “My mother lives in constant fear,” she says. “We’re all in despair!” At this instant, the door to the Freuds’ building clanks and the slender, dark-haired girl steps out, stops dead, and stares at Günter. No sooner does she see that he has noticed her than she turns and hurries off down the sidewalk, stopping twice to look back and stare at him again. The fact that she is on the street means Günter is late for his appointment. He apologizes to Anna and hurries into the building, taking the stairs two at a time.

The Professor is always silent, so much so that several times during the weeks after the incident with the fallen cigar, Günter cranes his head around on the couch to make sure that Freud is still there and awake. The primary result of these episodes is embarrassment, because Günter always finds his famous analyst looking right at him from beneath a cloud of liver-colored smoke and has to suffer a gentle rebuke. The first time, Freud merely shakes his head and finger reprovingly. The second time, he smiles and says, “Oh, ye of little faith!” The third time, after the Professor says, “I’m always listening, and I hear your every word,” Günter asks, “Why are you playing God?”

At first Freud seems taken aback; then he smiles. “Why do you say I am playing God?”

“Because you are! It’s obvious.” Günter’s heart is pounding. He is surprised at the intensity of his anger.

“On what evidence do you base this judgment?”

Günter sits up and swings his feet to the floor so that he can see the Professor without straining his neck.

Freud stirs his finger in a counterclockwise direction. “It would be best if you were to lie back down.”

“That’s exactly what I’m talking about!” says Günter. “You’re always giving me commands—or commandments!” He meant the last two words as a minor joke, but Freud neither laughs nor speaks. There is a long moment during which Günter is afraid to meet Freud’s eyes, and when he finally does, the Professor looks profoundly bored. “Tell me more,” he says.

Günter lifts his feet back onto the couch and lies down, both ashamed and relieved at his capitulation. “You accuse me of not having ‘faith.’ You tell me that you can hear my every word, which conveys the distinct implication that you can also hear my thoughts, even those inaccessible to me. And you are so silent. When I am lying here, I can’t even see you. You’re a perfect Deus absconditus! And you are terrifying! You know everything—you sit in judgment and you hold my life in your hands. If that doesn’t sound like God, I don’t know what does.”

“Very interesting,” says Freud. “But I am wondering to what extent my God-like qualities are actually the result of anything I, myself, do.”

From twelve-thirty to seven-thirty every weekday, Günter dissects the nervous systems of octopuses at the Physiological Institute of the University of Vienna. He has just finished work, and his hands smell of formaldehyde as he steps out onto Schwartzspanierstrasse. Shreds of gold and rose drift across a teal sky, and blackbirds in the scattered lindens of the park behind the Votivkirche conduct their pensive evening improvisations. A young woman in a forest-green cloche hat is sitting on a wrought-iron bench under one of the trees with an open book in her lap. In the granular dimness of the gathering dusk, Günter doesn’t realize she is the slender, dark-haired girl from Professor Freud’s office until he is directly in front of her.

He stops.

At first she seems entirely oblivious to his presence. Then her eyes rise slowly, as if in contemplation. When she spots Günter, her mouth falls open: “Oh!”

“Sorry,” he says. “I didn’t mean to startle you.”

“What are you doing here?”

He gestures behind him. “I work at the Physiological Institute.”

She closes her book. “How amazing!” She smiles, but in the semi-uncomfortable way a woman might smile at someone who has just squeezed in beside her on a streetcar.

“What about you?” he says.

She doesn’t seem to understand.

“Why are you here?”

“I live near here—on Glasergasse. I come here every afternoon to read. It’s so quiet. Relaxing.”

He grunts in surprise. “I walk this way every evening, but I’ve never seen you.”

“Well . . . ” She smiles again, but this time the smile is ironic. “No doubt you have much more important things to think about.”

“Not likely!”

He laughs. She doesn’t.

He wonders if she is telling the truth. His first thought when he recognized her was that she had followed him from Freud’s building.

There is a brief moment during which they both seem unable to think of anything to say. Then she lifts her hand as if to shake on a deal: “Josine Rosenthal.”

“Pleased to meet you!” Günter shakes her hand. “Officially, I mean.” Her skin is cool and soft, her fingers so slender they seem to melt away in his grasp. He starts to speak: “I’m—”

“Günter Zeitz!” she announces. “Doctor Günter Zeitz!”

He laughs. “How did you know?”

“The old man told me.”

“Really?”

“Oh, yes, he talks about you all the time!”

Günter is more than a little surprised to hear that Professor Freud deems him worthy of discussion. “Nothing terrible, I hope.”

She doesn’t answer, only looks up smiling, watching his face.

“Uh-oh,” he says.

She laughs. “You don’t have anything to worry about! In fact—” She cuts herself off. “Well, never mind.”

“What?”

“It’s nothing.” She freezes for a moment, her mouth open, her eyes vaguely mirthful.

Günter waits, but the topic has been concluded.

When Günter was four or five years old, he asked his mother what the phrase “I give up” means. They were in the kitchen. His mother was having coffee at the table. The world outside the windows was filled with sunshine. Crows called to one another from the trees. “Sometimes,” his mother said, “you want something to happen. You work very hard to make it happen, and maybe it is the only thing you can think about for a very long time. But then, one day, you realize that it is not going to happen, that there is nothing you can do to make it happen, and so you say, ‘I give up,’ which means that you are going to stop trying. You stop trying even if you still want that thing very, very much. ‘I give up,’ you say.”

This explanation brought a terrible fear into Günter’s life, because what he thought his mother was saying was that when you “give up” on something you have decided to die. And there was something in the tone of her voice that made him think she herself might decide to die, that one day she would realize she was never going to get something she wanted dearly, and so she would give up on life—and thus abandon him absolutely and forever.

Günter does not remember what made the notion that she would end her life seem so likely, or even why he would think anyone could possibly want to end their life. Nor does he remember where he first heard the phrase, or what made it stand out for him.

He lived with this fear for many years.

Günter is just taking a seat when the door to Professor Freud’s chambers opens and Fräulein Rosenthal dashes out. Günter instantly straightens up and steps toward her, smiling, preparing to wish her good day. A look of horror crosses her face. She waves her arm back and forth in the air between them, as if to erase him, then dashes into the foyer, grabs her coat and hat, and is out the door before she has even put them on. A few minutes later, the Professor opens the door to the waiting room, and Günter is still standing, looking at the front door.

“Fräulein Rosenthal seemed upset,” he says.

The Professor makes a non-committal noise. “She told me she ran into you on the street and you had a conversation. Is this something you’d like to discuss?”

Günter suddenly feels a fierce aversion to telling the Professor anything at all about this strange woman. “Not particularly,” he says.

“Very well then.” The Professor stands aside to let him into his office.

Fräulein Rosenthal is sitting on the bench. “Hello,” she says, looking up and only half meeting Günter’s eye, as if she expects to be scolded.

“It’s good to see you,” he says, anxiously running his fingers through his tangled hair. “I was worried about you.”

She casts him a sharp glance.

There is an open book in her lap—a collection of Jung’s essays. She seems mere pages from the end. Placing a slip of paper between the pages, she closes the book, holds it with both hands atop her knees, and looks up, her expression tense, though not angry.

“I’m sorry.” She attempts a smile. “Things have not been going well for me lately.”

“Professor Freud said you were ill.”

“Did he?” She sighs heavily. “Well, you shouldn’t believe anything he says.”

“Did something happen?”

“He’s a charlatan and a fool!”

Shocked by both the accusation and the ferocity with which it is made, Günter sits down beside her on the bench. “There must be some kind of misunderstanding.”

“There’s no misunderstanding. He won’t listen to me, and he says things that are not true. And anyway, no man has the right to say such things to any woman.”

She is echoing Günter’s own uncertainty about Professor Freud, but even so, he suspects there is something defensive in her rage, perhaps as a result of a prematurely rendered insight. “Do you want to tell me what happened?”

Her eyes fall to the book in her lap. “No.” She looks over at him and attempts another smile. “It’s all so boring. I’d rather not think about it.”

Adolf hitler: All this was inspired by the principle—which is quite true in itself—that in the big lie there is always a certain force of credibility; because the broad masses of a nation are always more easily corrupted in the deeper strata of their emotional nature than consciously or voluntarily; and thus in the primitive simplicity of their minds they more readily fall victims to the big lie than the small lie, since they themselves often tell small lies in little matters but would be ashamed to resort to large-scale falsehoods. It would never come into their heads to fabricate colossal untruths, and they would not believe that others could have the impudence to distort the truth so infamously. Even though the facts which prove this to be so may be brought clearly to their minds, they will still doubt and waver and will continue to think that there may be some other explanation.

Günter Zeitz and Josine Rosenthal are sitting in a noisy restaurant. At the center of their table stands a squat Chianti bottle in a straw bodice, with a candle stuck into its mouth. On the menu they find veal rollatini next to Wiener schnitzel and osso buco next to goulash. The waiter tells them the cook is Italian. They talk about Italy, where neither have ever been and both want to go. “Rome,” says Günter. “Florence,” says Josine. “Venice,” says Günter. “Yes, Venice,” says Josine. They laugh. They talk about oysters, garlic, the Sistine Chapel, Pompeii. They talk about the man across the room with the bright red face, whose eyes seem about to pop from his head. Their feet touch under the table. They apologize simultaneously. They laugh. They order oysters to share, and a bottle of Chianti. Josine orders the veal rollatini and Günter the osso buco. He thinks this meal will cost him a month’s rent, then decides not to think about it. They agree that Italians are much more alive than Austrians, Germans, or Swiss. They agree that the reserve of German-speaking people is due to the weather: the gray skies, the winters that kill off children, old people, livestock. Neither admits to being anxious or to hardly being able to wait for the wine to come. They agree that Jung’s idea of an inherited unconscious is uncomfortably close to National Socialist ideology. Are the National Socialists an actual threat? “Who knows!” says Günter. They both laugh. Günter asks and Josine answers, “Jewish . . . And you?” “I am nothing,” Günter says. “Religion makes no sense to me. I can’t believe in God.” “Then we are the same,” she says. The wine comes. They exchange bright glances and small smiles. They clink glasses. After her first sip, Josine says, “Now I have arrived in Italy!” “Where are you?” says Günter. “I’ve just gotten off a train in Rome.” “And where will you be when the bottle is finished?” “Venice!” They laugh. They toast. “To Venice!” The oysters arrive. Josine picks one up and holds it in front of her mouth. “This always feels like something people shouldn’t do in public. You mustn’t look at me!” But never once, as she touches her lip to the ragged shell edge, sucks the glistening gray glob onto her pink tongue and swallows, does she cease to stare into his eyes. “You didn’t do what I said!” she says. He lifts an oyster to his mouth and says, “Now you mustn’t look at me!” Their eyes never part.

Günter swings his feet off the couch and sits up. “Do you mind?” The Professor shakes his head. “There is something I have been wanting to talk to you about for a long time,” says Günter.

The Professor is silent.

Günter continues: “I don’t see why you define aggression as a manifestation of the death drive. When a man fights for his life, or to protect his family, or to ensure his access to food, how is that not a manifestation of his desire to live and to preserve life, which is to say of the life drive and the pleasure principle?”

Günter stops talking.

Freud shakes his head and smiles.

“My dear Zeitz, you will never become a true psychoanalyst unless you realize that the terrible force of our adversary, the unconscious, arises entirely from its profound and relentless irrationality. Look at the last war. In what way was that moral catastrophe a struggle to protect and propagate human life? And the same might be asked of these brown-shirted thugs in Bavaria. Our job as psychoanalysts is to defend our species from the worst effects of its ingrown perversity.”

Günter emerges from Freud’s building and notices Josine standing two paces down from the door. She is looking at an old man on the sidewalk opposite pulling a child’s wagon loaded with candlesticks and rattling plates. Her brow is pinched, her mouth crinkled and white, and both her hands are balled into fists beneath the elbows of her tightly crossed arms. As Günter steps toward her, his shoe scrapes on the pavement, causing her to look his way. “Thank God!” she cries, but doesn’t move.

“What’s the matter?” he says.

“I wasn’t sure I could wait any longer!” She is shivering—even though the sun is out, the breeze is silky and warm, and she is wearing a coat.

“Is something wrong?” he asks. “Are you ill?”

Her laugh is hollow. “No, no. I just want you to do me a favor.”

“What? I don’t have much time. I have to get to the laboratory.”

“I want you to take me to your apartment.”

“Why?”

“I can’t tell you.” She laughs again. She rubs his shoulder. “I’ll tell you when we get there.”

“But I can’t! I have to be at work in fifteen minutes.”

“Tell them you’re sick. There was something rotten in your lunch.”

“But why? What’s going on?”

At this question, she places the knuckles of her fist against her lips. Then her hand falls, she stands on her toes, brings her lips to his ear, and whispers, “I want you to make love to me.”

They walk with their arms around each other. Several times he stops to kiss her, half experimentally, half because it just seems something he should do. Once, on a vacant street, he slips his hand between the buttons of her coat and cups her breast through her blouse. She whispers in his ear, “Wait. Just wait.” Otherwise, they hardly talk. He mentions that he is becoming angry at Freud; she is not listening.

Once they are inside Günter’s apartment, he becomes ashamed. His bed is unmade. His dishes from breakfast and last night are piled in the sink. His only window, curtainless, looks out into a grate-covered light well. The air smells of liverwurst and unwashed socks.

Josine walks to the center of the room, turns, and says, “Here we are!”

After that she just stands, blank-faced and listless, like a patient waiting in an examining room. He kisses her, and her lips are like spongy rubber across her teeth.

Josine is sitting beside the table in her kitchen, elbows resting on her knees, hands on her temples, fingers in her hair. She is speaking in a low voice. “The next time was when my parents went to live in New York for six months and I stayed in his house so that I wouldn’t miss school. I was thirteen. He came to me every night. He told me he was teaching me how to be a woman. He told me I should be grateful. That my husband would be grateful. His wife knew. She wouldn’t even look at me at breakfast. And she wouldn’t talk to him. One day when we were passing in the hallway, she grabbed me by the shoulder and slapped my cheek. She told me I was a disgusting whore. I did tell my mother that she’d slapped me—though I said I had no idea why. When I told my parents I never wanted to see him or his wife again, that slap was my excuse. No one ever asked questions.”

The Professor invites Günter to have dinner with his family. The pocket doors to the dining room are shut. Everyone waits in the parlor, sipping glasses of amontillado. Frau Freud and her sister, Fräulein Bernays, sit side by side on a leather couch, the one wearing a black shawl, the other white. They speak like a single brain in conversation with itself. When Frau Freud tells Günter, “We had been hoping our son—” Fräulein Bernays interjects: “Oliver, the famous counter—”

“Minna!” cries Frau Freud. “What are you saying!”

“He’s a counter,” Fräulein Bernays tells Günter. “He counts everything. If you asked, he could tell you exactly how many cigarettes there are in that bowl.” She points to a silver bowl at the center of the coffee table. “He would also know how many buttons there are on your shirt and how many eyelets in your shoes.”

“It’s just that he’s mathematically inclined,” insists Frau Freud. “He’s an engineer.”

“A civil engineer,” says Fräulein Bernays. “In Berlin.”

“In Berlin,” affirms her sister. “We had been hoping that he would be visiting us now—”

“—but his wife is pregnant.”

“A difficult pregnancy—”

“—so he doesn’t dare travel.”

Günter is sitting on a chair directly opposite the sisters. Anna is just beside him. She plays no role in the conversation, though she does keep casting him glances and smiling in a way that makes her look as if she is gasping. She is expressing her own embarrassment, perhaps—or trying to ease his.

No sooner had he walked into the apartment than he realized, from the glances exchanged between the sisters and the Professor’s uneasy frown, that he had been invited in the hope that an affinity might arise between him and Anna.

The Professor hasn’t taken a seat. He is pacing along the wall, fidgeting, taking his hands in and out of his pockets, making querulous noises deep in his throat. “Oliver shows signs of obsessional neurosis,” he says. “I have been encouraging him to go into analysis with Eitingon, but he won’t listen to anything I say. He is a great disappointment.”

The room falls silent.

When the maid opens the doors to the dining room, everyone who has been seated rises. The Professor gives Günter a curt quarter-bow from the waist and says, “I will see you tomorrow!” There is a door just behind him. He opens it and leaves.

Anna leans over and whispers, “Ever since his operation, he hasn’t eaten in front of anyone but the family. He wants, above all else, to retain his dignity.”

Günter has no need of the toilet. All he wants is to escape the tedium of the polite dinner conversation he, Anna, her mother, and her aunt are working so hard to maintain. When he asks where he might find the water closet, Frau Freud nods toward the door through which her husband disappeared. “On the left,” she says.

Günter finds himself in a dark hallway, with no discernible apertures along its left wall. He opens the first door on the right. While the interior is entirely lightless, he can tell from the smell of fur and the muffling of sound that it is a coat closet. The next door is to the bathroom, so the one just after must be to the toilet.

But no.

Sigmund Freud, in a sleeveless undershirt and rumpled trousers, is standing in the middle of a bedroom, holding a dress shirt by its collar and one tail, apparently checking for stains. The skin of his outstretched arms is crinkled and pallid, his muscles atrophied. A bush of gray-brown hair fans from his armpit.

“Oh, sorry!” says Günter.

Freud, startled, looks straight into Günter’s eyes.

“Sorry,” Günter repeats, backing out the door.

Freud is waving his shirt in the air, making off-key yawps and groans, the expression on his face desperate.

Günter doesn’t know whether to pull the door all the way shut or step back into the room.

More yawps. A seal-like bellow.

On the table, beside the single bed, there is a plate, and on the plate, there is an object that looks like a lump of meat and teeth.

Freud flings his shirt onto the bed and holds up one finger. As he makes his way toward the bedside table, he gives Günter a significant glance and, once more, holds his finger up.

Günter remains motionless in the doorway.

The Professor picks the object up off the plate and puts it into his mouth. After some adjustments requiring fingers from both hands, as well as much loud hacking and sucking that sounds like nothing so much as strangulation, Freud lowers his hands and says, “Ah, Zeitz! I was just thinking of you.”

The night before coming to dinner at the Freuds’, Günter was eating at the Hotel Imperial with Josine; her brother, Josef; and her sister-in-law, Herta.

“But he’s a laughable anachronism!” said Günter, a fork in one hand, a knife in the other, and a half-chewed bite of potato lodged in his cheek.

“Not so laughable,” said Herta.

“And not so anachronistic,” said Josef.

Günter tongued the potato into the center of his mouth, chewed, took a sip of his wine.

“He fills the streets with passionate Bavarians,” said Josef. “I wish they were anachronisms, but as far as I can tell, they are very much of our era.”

Josine had hardly said a word all evening, but had been drinking wine at such a rate that her eyes no longer focused on any one point in space. Her elbows rested on the table, and she was holding her wineglass with both hands in front of her face, but so loosely it seemed in danger of falling onto her plate.

“He’s a troglodyte!” said Günter. “His economic program is based entirely on an anti-Semitic fantasy, so it is guaranteed to fail. He may appeal to the credulous Protestant petite bourgeoisie, but all people really want are jobs. If he ever actually follows through on his promises, there’ll be rioting in the streets, the stock market will plunge—people won’t stand for it!”

Günter is sitting on the corner of the Professor’s bed. Freud, still in his sleeveless undershirt, is sitting on a wooden desk chair, one hand on each of his knees, fingers spread, clutching the knobby bones underneath. “I was once like you,” he says, “believing there was a nobility to certain ideas—or a veracity—that allowed them to transcend the minds in which they were conceived and through which they passed.”

Günter is filled with a frantic restlessness. All he wants is to make his excuses and leave, but he is incapable of resisting the Professor.

“You know Rilke, of course,” says Freud.

“Yes,” says Günter. “Not personally, but . . . ” He doesn’t finish.

“One afternoon,” says Freud, “I was walking with him through the countryside. It was a summery day in early September. The sun was golden, the fields filled with flowers. But he denied that any of it was beautiful. The fact that it would wither in mere weeks filled him with despair.‘There is no beauty apart from the eternal,’ he said. I thought that the most juvenile of affectations and had to restrain my irritation as I argued that the very transience of the beauty around us only made it more precious—”

“Even its transience is transient,” says Günter, hoping to anticipate Freud’s points and thereby hasten the end of this interview.

The Professor waves away the interruption.

He is standing now, pacing in front of the bed, his feet bare and veiny, his toenails thick, in need of clipping.

“Yes. Of course,” he says. “I made that point too. But my main argument was that beauty is intrinsic to the beautiful object, to its particular configuration of color, form, structure, and so beauty is independent of context. Thus, if an object is beautiful in a particular instant, it is always beautiful, and in that way eternal.”

“What did he say?”

“Oh, he was as contemptuous of me as I was of him. He thought I was naïve, blinded by scientific pragmatism. I came away from that conversation thinking I had wasted my time. But I have been arguing with Rilke in my mind ever since: every time I contemplate a beautiful idea, whenever I think there might be something redemptive in the life drive, or even in aggression, insofar as it is the force of conscience, I wonder if Rilke would think me vacuous, self-deceived. And tonight, it came to me in a flash: Rilke was right! I am vacuous! I’ve been living in a fantasy!”

Freud stops pacing, his emaciated arms stiff at his sides, his hands in tight fists, his old man’s face constricted, yellowed, insect-like.

“There is, in fact, no beauty apart from the eternal—which is the opposite of existence: a void, a nothingness, airless, endless, dark and dead, in the midst of which existence—especially human existence—is a senseless accident. And when we encounter the eternal, we encounter only its absolute and implacable indifference to us, which our flesh-bound minds can conceive of only as cruelty. And this is the most important thing, because as cruelty, the eternal seems so magnificently heedless that it feels like pure freedom to us, and so it is awe-inspiring and profoundly beautiful: the only thing in all of creation that we can truly love. And in most people, such love takes one of two forms: either we make ourselves abject before the eternal in the hope that it will not destroy us, which is to say that we worship it; or we attempt to take the eternal into ourselves, which is to say that we make ourselves the agents of its cruelty.”

Freud has stopped speaking. His eyes inside the round lenses of his glasses are fixed on Günter. They glitter. They do not move.

Günter looks away. His mouth has gone dry.

When at last he draws a breath to speak, Freud’s arm flies out, palm flat, upraised. “Stop! No words!”

Günter is at a party in a palace ballroom. The women are dressed in ankle-length gowns of muted floral colors. Most of the men wear tuxedos with silk waistcoats, though some are in military uniforms with chin-high collars and heavy medals arrayed across their chests. A string quartet is playing, while overhead naked men and women float amid the gold-tinged clouds of a summer sky. Günter holds a glass of wine and is talking to a woman who looks like a little girl in her mother’s clothing. The sleeves of her green satin gown are rolled up at her wrists, and its skirt rumples against the polished floor. She too holds a glass of wine, but she is weeping. When Günter asks what is wrong, she tells him, “You shouldn’t be here.” “Why?” he asks. “Because you are dead.” And now it seems that he is walking beneath an umber sky, the palace a heap of smoldering rubble behind him. He crosses its ruined terrace and descends a set of steps into a gully, where a gray dog lies on its belly in long grass—it is Schatzi, the Weimaraner mutt Günter’s family owned when he was a child. “Hey, girl!” Günter crouches and holds out his hand. The dog stands. It slinks toward him, sniffs his fingers, then bares its fangs and lunges. Günter leaps back and kicks, feeling the impact of his foot against the dog’s skull. The dog yelps, reels, and runs. It has something in its mouth: a piece of bloody meat. Günter looks at his sleeve, which seems to have been brushed with red paint. He wonders if the sleeve has been ripped but cannot tell. Another dog is slinking out of the grass, head lowered, fangs bared, and now another, then several more. Günter is surrounded. The dogs are closing in. He has no choice but to fight.